Canadians have another facet of national defence right under our noses

The current trade war with the U.S. means Canada must confront whether its domestic food...

Talk about the government fox guarding the hen house. BC Hydro has applied to the provincial government for a new licence that will allow it to demolish Peace Valley protected old-growth forest, migratory bird habitat and a rare wetland for the Site C dam

.

Next up on the Site C chopping block is 1,225 hectares of Crown land — an area larger than three Stanley Parks — that includes a spectacular and rare hillside wetland called a tufa seep. The seep likely took thousands of years to form, making it older than the Hanging Gardens of Babylon and the Great Wall of China.

Even if the government required BC Hydro to place a no-logging zone around the seep to protect its unique biodiversity values, it will be ultimately destroyed by the Site C reservoir. The seep is one of at least seven of the ancient wetlands that lie within the Site C project area, a concentration that botanist and lichenologist Curtis Bjork said is “unlike anything I’ve ever seen.”

Bjork, who has studied the Peace River Valley since 2008, said the tufa seep in the area included in BC Hydro’s application likely began to form 10,000 years ago and is one of the most stunning he has ever viewed.

When DeSmog showed Bjork a recent photograph of the seep he was silent for a moment. “Who could not love a place like that?” he asked. “This is one of the biggest tufa seeps I’ve ever seen.”

Rare hillside wetland BC Hydro applied to demolish for Site C construction. Photo: Garth Lenz

A rare image of the ancient wetland known as a tufa seep. Photo: Garth Lenz

Bjork described tufa seeps as similar to “islands in the sea”: isolated habitats where mosses, liverworts, lichens and vascular plants adapt to unique mineral and hydrological conditions, giving rise to populations of rare and at risk species.

“That’s why each tufa seep you get to as a botanist you’re very excited about because you have no idea what you’re going to find there. And by extension it’s also one of those habitats where you can expect to find rare species. This is an unusual habitat in the landscape. There are not a lot of tufa seeps out there.”

Bjork, a botanical consultant and research associate with the University of British Columbia Herbarium, said the stretch of the Peace River that would be flooded by Site C is home to moss species that are among the most diverse he has encountered anywhere in western North America during two decades of fieldwork.

“We found tufa seeps that were so large that they had waterfalls and little pools enclosed in calcium carbonate rims. The pools are like these tiers that you can step up like a staircase and the water will spill from one pool to the next to the next to the next.”

Cascading pools in a Peace River tufa seep are slated for destruction to make way for the Site C dam and its reservoir. Photo: Garth Lenz

One tufa seep found in the Site C flood zone by Bjork and his colleagues was so big it had a chamber they could walk into. “The ceiling was coated in mosses and liverworts and the walls were just dripping with this carbonate rich water.”

The “seep” reflects the slow movement of water, some from as far away as the Rocky Mountains, as it moves through layers of underground plateau and sheet-like aquifers. By the time the water drips out of slopes above the Peace River it carries a high mineral content, most notably calcium carbonate. Bjork said deposits of calcium carbonate build up over thousands of years, much like the stalactites and stalagmites found inside limestone caves.

Specialized mosses grow on the calcium carbonate deposits. In a race for survival, they must grow faster than the deposits themselves. Their lower leaves become encased in the carbonate, essentially becoming rock. The older portions of the mosses die away or are eaten by bacteria, leaving spongy pores in the calcium deposits: the tufa.

BC Hydro said in a report that five out of seven of the known tufa seeps along the Peace River will be destroyed by Site C’s reservoir. The Crown corporation, which described the seeps as “of high conservation value,” said the sixth seep will be crossed by a proposed transmission line and the seventh “may be affected indirectly” by Site C.

BC Hydro said it will try to compensate for the loss of the seeps and other wetlands by creating new wetlands with similar functions, a statement questioned by Bjork. “How could they recreate tufa seeps? I’d like to see such a mitigation plan.”

Bjork said he does not understand how the zone that includes the tufa seep photographed by DeSmog can be stripped of vegetation when court cases against Site C are underway and the project could be stopped.

“Canada has the worst environmental laws and regulations among all developed countries. Far too few Canadians appreciate that. They just assume that this is Canada and therefore everything is great.”

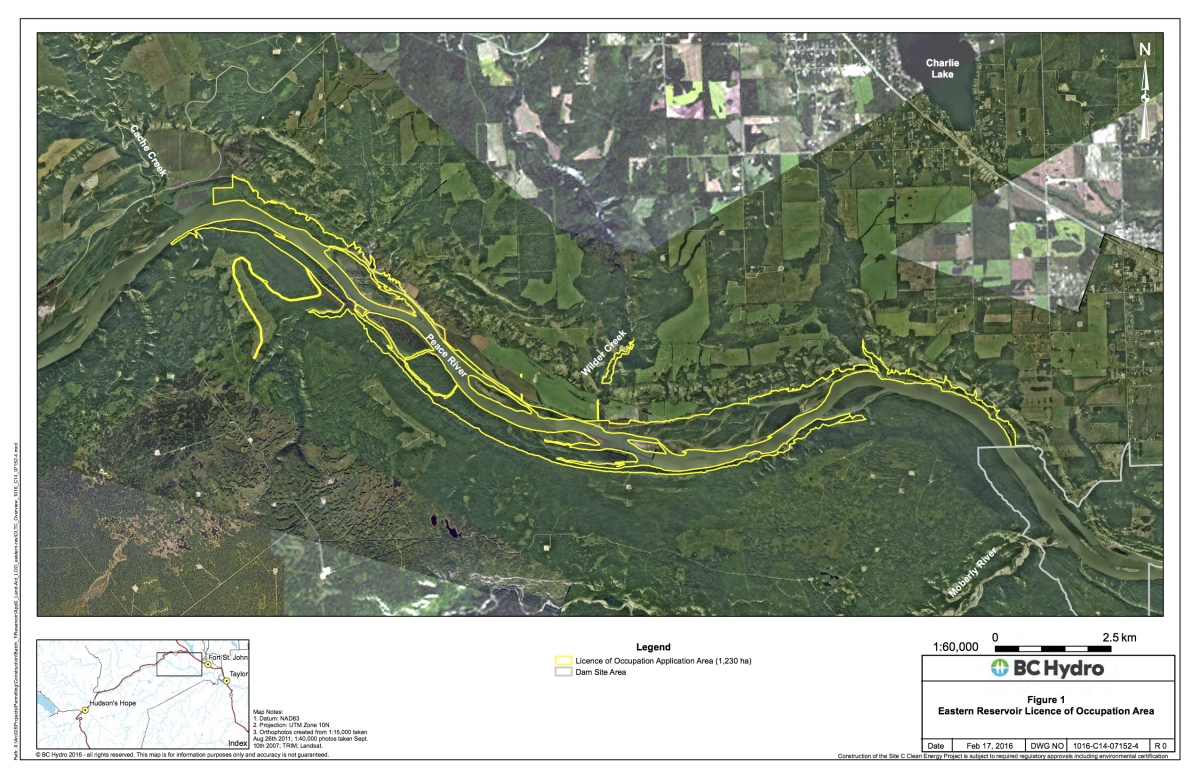

BC Hydro’s application for a “licence of occupation” for vegetation clearing was made to the Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations’ FrontCounter B.C. division, “a single window service for clients.” The planned clearcut along the banks of the Peace River will stretch all the way from near the Rocky Mountain Fort site to Cache Creek, close to the home of farmers Ken and Arlene Boon.

The zone must be “cleared,” according to a FrontCounter email to the Peace River Regional District, to make way for reservoir filling and erosion when the $8.8 billion dam becomes operational in 2024, flooding more than 100 kilometres of the Peace River and its tributaries.

Map detailing land slated for clearing along the banks of the Peace River. Image: BC Hydro

The area included in BC Hydro’s application is also important nesting habitat for migrating birds such as the Canada warbler, a bright yellow-coloured songbird that is listed as threatened under the federal Species at Risk Act.

Clear-cutting and bulldozing migratory bird habitat is prohibited during nesting season but permitted during winter months when birds are absent.

According to an Environment Canada presentation, a cluster of Canada warbler detections have been documented in an area on the south bank of the Peace River that is included in BC Hydro’s application for clearing, as well as close to the historic Rocky Mountain Fort site, which is slated to become a waste rock dump for Site C.

Canada warblers have experienced a seventy-five per cent decline over the past 40 years, according to the Boreal Songbird Initiative, largely due to climate change and the loss of habitat from industrial activities such as logging and hydroelectric dams.

The warblers are among tens of thousands of birds that migrate north from as far away as South America and use the low-elevation Peace River Valley as a flyway, seeking shelter from late spring and early fall snowstorms in the valley’s relatively mild climate.

They include about 200 migratory bird species, according to Environment Canada, which calls the Peace River Valley one of Canada’s most “species rich” places for perching birds, including species at risk such as the olive-sided flycatcher and bay-breasted warbler.

Karen Bakker, professor of geography at UBC and Canada Research Chair in Political Ecology, said the impending destruction of migratory bird habitat and tufa seeps are just two examples of Site C’s devastating environmental impact.

“Our research showed that Site C has more significant adverse environment effects than any other project ever reviewed [in] the history of the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act,” Bakker said.

Bakker said Site C, despite its unprecedented capital cost and ecological impacts, received an “incredibly impoverished review in economic and environmental terms,” due to the constraints imposed on the Joint Review Panel that examined the project for the federal and provincial governments.

“Site C is not cleaner or greener than the alternatives.”

Hydro’s application for a licence to clear also includes protected Old Growth Management Areas, part of a larger area the B.C. government has set aside to become the Peace Boudreau Protected Area. Rod Backmeyer, the retired FLNRO biologist who wrote a management plan for the area, described the forest slated for Site C clear-cutting as even more important than the Great Bear Rainforest from a biodiversity viewpoint because “there’s far less of it.”

BC Hydro’s Site C spokesperson Dave Conway did not respond to two calls and an email from DeSmog asking for additional details about the FrontCounter application and a timeline for clearing the Crown land. According to FrontCounter, BC Hydro’s application to allow the next phase of Site C clearing is “under review” following a public comment period.

But the application process is merely a formality, as Premier Christy Clark has vowed to push Site C construction “past the point of no return” despite on-going court cases against the dam by Treaty 8 First Nations.

Bakker said she didn’t want to be overly cynical but “BC Hydro and the provincial government want to be seen as going through the motions, and this is going through the motions.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

The current trade war with the U.S. means Canada must confront whether its domestic food...

Residents and nearby First Nations wanted a new environmental impact assessment of the contentious project....

Growing up, Christian Allaire loved spending summers with his cousins in his grandma’s backyard, near...