Battling a hungry beetle, this Mohawk community hopes to keep its trees — and traditions — alive

An invasive pest threatens the survival of black ash trees — and the Mohawk art...

When the news broke this week that former B.C. premier John Horgan was taking on a new role with one of the most influential mining companies in the country, it inadvertently shone a spotlight on one of the province’s sorest spots: coal mining in the Elk Valley.

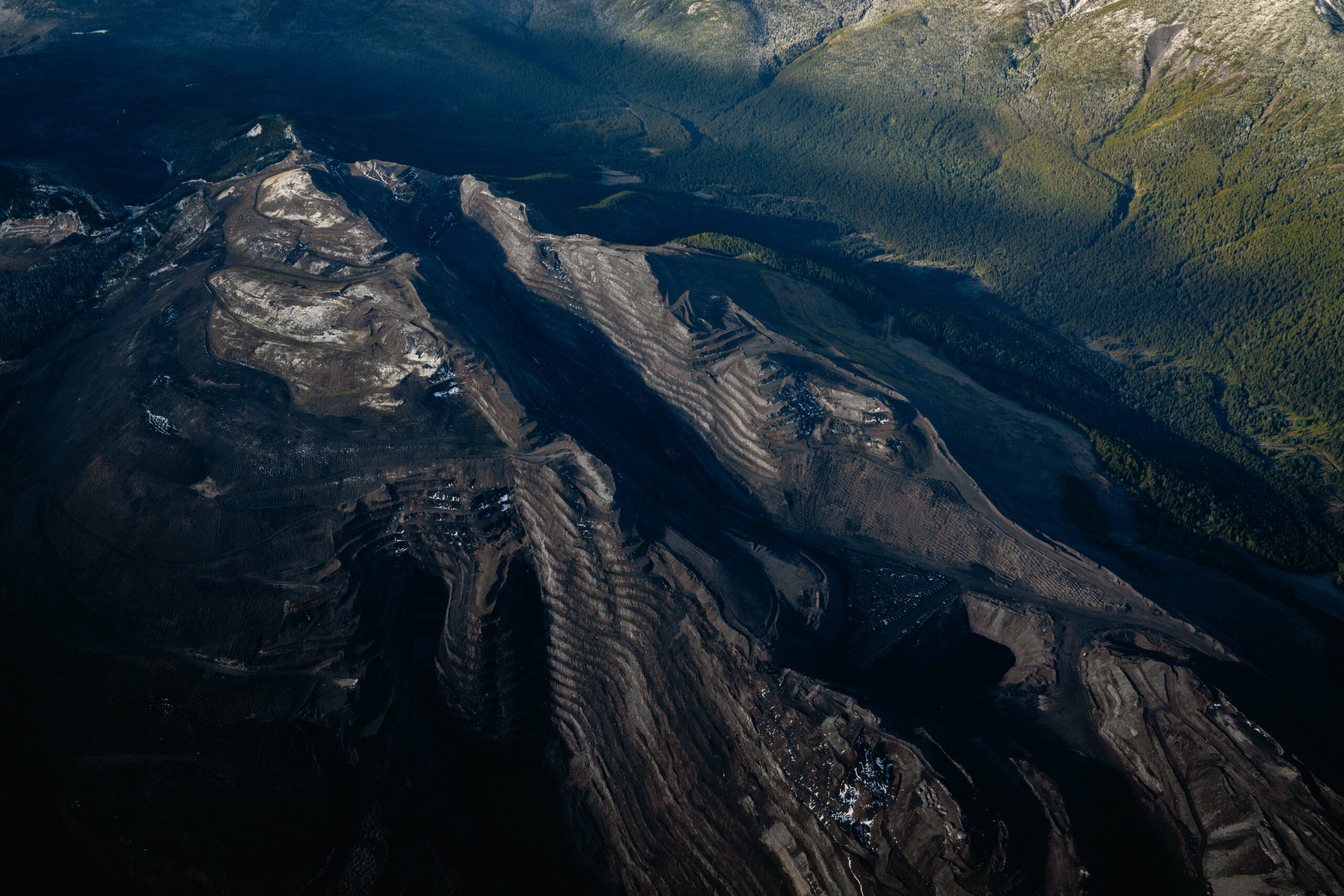

It’s a strangely quiet story in B.C., given its Hollywood-level proportions: huge mountains are shaved down to nubs in bustling around-the-clock coal operations that go on unabated, 365 days a year. Enormous piles of waste rock — left exposed to rain and snow and wind all year long — send a constant trickle of contaminants throughout the watershed and into meandering rivers and creeks known for their prized trout populations. Starting in 2014, scientists warned the pollution, especially selenium contamination, could become extremely dangerous for fish and birds. And then fishermen began pulling severely deformed trout out of the rivers.

But it gets much worse. Because the leaching is so difficult to control, selenium pollution is now a problem all throughout the watershed and even in the bodies of water that cross the B.C.-Montana border. You don’t have to watch Yellowstone to imagine how the good people of Montana feel about an uncontrolled stream of selenium contaminating their waters and poisoning their fish.

Experts warn selenium could be a problem in the valley for hundreds or even a thousand years, especially given the colossal size of waste piles.

In the meantime, warnings issued by scientists about the danger of letting selenium build up in the ecosystem appear to be playing out, with fish populations collapsing in rivers immediately downstream of the mines.

It’s bad enough the pollution in the Elk Valley, a place some British Columbians haven’t even heard of, was a focus of talks between Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Joe Biden during the U.S. leader’s first presidential visit to Canada two weeks ago.

These are big problems. Monumental, even. So, it’s a wonder to read Horgan’s recent words as he takes up his new mantle on the board of Elk Valley Resources, a planned spinoff from Teck Resources to manage the company’s four coal mines in the valley (assuming a new takeover proposal doesn’t get off the ground).

“I’ve got other things that I am going to be working on that may be more to the taste of those who would kick up some dust, but the people that are kicking up dust, oftentimes, kick it up for the sake of kicking it up,” Horgan told The Globe and Mail.

“I don’t have a lot of time any more, none in fact, for public comment on my worldview, or what I am doing with my time. I don’t want to be snippy about it, but there are others that are making policy decisions.” The article also mentions Horgan said he will work to ensure the company is respecting its obligations to Indigenous communities and the environment as well as mine workers and shareholders.

Horgan’s words are perturbing for those who were asking for greater accountability for Teck’s coal mines during the time he was, in fact, making policy decisions. That time, it’s important to remember, extended to mere months ago.

Nasuʔkin (Chief) Heidi Gravelle of the Yaq̓itʔa·knuqⱡiʾit (Tobacco Plains Indian Band) told The Narwhal in late 2021 that “prior to the mines, people could drink out of the rivers.” But not anymore.

“Nobody will eat fish out of there because of the contaminants, which is sad,” she said. “That was a huge part of our history.”

“The mines have put some work into fixing the selenium problem. But it’s not enough. There needs to be stronger environmental regulations at the end of the day, and accountability — so raise the bar and if you don’t meet it, you’re done,” she said.

Horgan did not respond to a request for comment from The Narwhal by time of publication.

During Horgan’s tenure, the Elk Valley saw an increase in selenium levels without any meaningful pushback from the province on Teck’s permits to operate. Although B.C.’s water quality guidelines say selenium levels must remain below two parts per billion to safeguard aquatic life, selenium levels in waterways across the valley are as high as 100, 200 and even 500 parts per billion.

The mines are permitted under a flexible regulatory arrangement called the Elk Valley Water Quality Plan that hoped to see selenium levels stabilized by 2023 and decreasing by 2030.

Instead, selenium levels in waterways all across the Elk Valley continue to increase despite hundreds of millions of dollars invested by Teck for more than a decade into water treatment plants that have struggled to successfully remove selenium and struggled to keep up with the pure volume of selenium. There is still no credible plan in place to handle the ever-increasing selenium levels that are now creeping up in connected waterways as far away as Idaho.

Yet this is despite the fact that selenium levels have become so high, they have threatened the safety of drinking water for communities in the Elk Valley, and both municipal and private wells in the region have at times been rendered unsafe for human consumption.

And, although some federal fines have been issued for Teck’s pollution, Ottawa is limited in its ability to respond because Canada lacks federal regulations for coal mining effluent. Under Horgan’s watch, B.C. fought against the introduction of such rules because they would negatively impact industry.

Rather than causing a reckoning for Teck, the company forged ahead with plans to expand its largest mine in the region.

In Horgan’s brief remarks to The Globe, he also suggested critics who might “kick up some dust” at his new role would be doing so under a false pretense, because he won’t be working for thermal coal but rather metallurgical coal, used to make steel. In doing so, Horgan is already falling into a false frame that overlooks the fact that Teck’s Elk Valley operations are an incredible source of carbon emissions.

According to Teck’s own disclosures, the company’s operational emissions in 2022 are estimated to be 2.8 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. That’s the same as 6.4 million barrels of oil consumed or the annual emissions from seven natural gas power plants, according to the Environmental Protection Agency’s greenhouse gas calculator.

But the lion’s share of Teck’s emissions come from the use of Teck’s steelmaking coal around the globe. According to Teck, based on the company’s 2022 sales, indirect emissions amounted to approximately 65 megatonnes, or the equivalent of more than 150 million barrels of oil or the annual emissions from 163 gas power plants.

It’s important to remember that Teck Resources is one of the most influential players in B.C.’s corporate-political landscape. For years before corporate and union political donations were banned in 2017, Teck consistently was one of B.C.’s top donors to political parties, giving out more than $1.5 million to the BC Liberals (now BC United) between 2008 and 2017. Teck donated $60,000 to the B.C. NDP, $50,000 of which came days before the 2017 election that saw the NDP take power.

In the years since corporate political donations were outlawed, Teck has registered 26 lobbyists who since 2020 have attempted to influence policy on a range of issues including climate policy, coal mining regulations and biodiversity. Between July 18, 2017, the day Horgan became B.C.’s premier, and Nov. 18, 2022, the day he stepped down, Teck registered 167 lobbying reports, including 30 meetings or communications directly with the office of the premier.

Horgan’s move is just the latest sign of Teck’s enormous clout.

While the former premier may not welcome outside commentary or wish to hear from those inclined to kick up dust about selenium in the Elk Valley, it seems less-than-genuine for Horgan to simply throw up his hands at a problem that festered and grew under his leadership.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. When I visited my reserve, Moose Factory,...

Continue reading

An invasive pest threatens the survival of black ash trees — and the Mohawk art...

Xatśūll First Nation is challenging B.C.’s approval of Mount Polley mine’s tailings dam raising. Indigenous...

As the top candidates for Canada’s next prime minister promise swift, major expansions of mining...