86 per cent of a river gone: First Nation calls on BC Hydro to let more water through

Katzie First Nation wants BC Hydro to let more water into the Fraser region's Alouette...

When Ross Muirhead and Hans Penner made their first trek of the season to the Dakota Bowl, slogging through cutblocks and then up into the ancient forest of giant yellow cedar and hemlock on the hills north of Gibsons, B.C., the hike turned into a spontaneous celebration that eight years of confrontation was finally behind them.

“It was a totally different experience going up there, knowing that this forest was now protected. We didn’t have that dark cloud hanging over us with the possibility of seeing road-building and contractors and trees falling and all that despicable destruction that we’ve seen in other areas,” said Muirhead, forest campaigner and founder of Elphinstone Logging Focus (ELF), a small Sunshine Coast-based environmental group that, for a decade, has been a thorn in the side of logging contractors and the government agency BC Timber Sales.

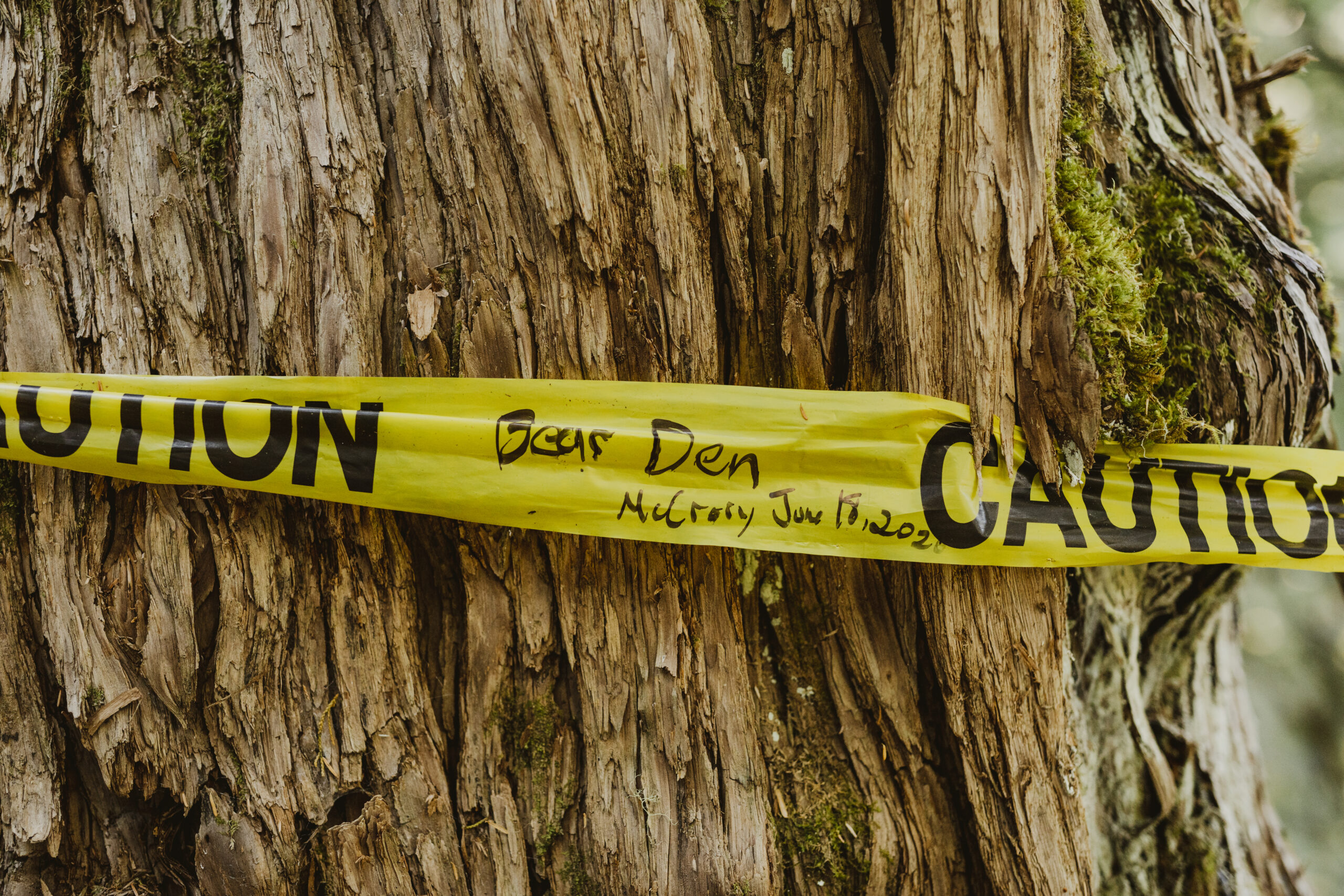

Penner, a longtime ELF forest campaigner, recalls the growing knot of dread he felt during previous hikes into the area as he wondered if he would find new flagging tape, marking cut blocks and road-building boundaries, in the old-growth forest that is part of Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) Nation territory.

“We have come across that so many times and it means devastation. We saw the flagging this time, but we know now they are not coming in, so it doesn’t bother us. We can enjoy it now — they didn’t win this one,” Penner said.

ELF has had a tough fight against BC Timber Sales, the agency that manages 20 per cent of the province’s annual allowable cut and decides which blocks of Crown land will be auctioned off to logging contractors.

BC Timber Sales appeared undeterred by a six-week blockade that prevented it from building a road into the Dakota Bowl area, accompanied by lobbying and letter-writing campaigns.

Despite reports from wildlife biologist Wayne McCrory documenting extraordinarily high number of black bear dens, two ELF-funded archaeological reports that noted 77 culturally modified trees — now included in the provincial heritage registry — and evidence the area contains trees well over 1,000 years old, the Dakota Bowl appeared in BC Timber Sales logging plans year after year.

When BC Timber Sales first put the block up for auction in 2015, no contractors were interested because of the difficulty of building a road into the remote area. Two years later, BC Timber Sales offered to subsidize road-building costs and, to sweeten the deal, it combined the offer with a block that had valuable Douglas fir and low road construction costs. It was enough to spark interest, but, following a successful blockade, the road-building contractor eventually walked away, Muirhead recalled.

One major point of contention was that BC Timber Sales refused to accept ELF’s expert studies which found the area potentially contained the largest number of culturally modified trees in the Lower Mainland.

“[BC Timber Sales] refused to accept that these were human-caused bark stripping. They hired an archaeology company who said First Nations would not come this far looking for yellow cedar. They tried all the tricks of the trade,” Muirhead recalled.

Then they brought in a helicopter and fallers and cut down eleven old yellow cedars with scars, including one that was 1,100 years old, to prove they were not culturally modified, Penner said.

“I was completely outraged and, of course, it was all paid for by the public.”

The battle to prove the trees had been marked historically by Indigenous people involved four different assessments by three companies. Two were brought in by ELF. One company identified 33 culturally modified trees while the other, following a peer review, said the marks could be cultural in origin, with some scars dating back to the 1500s. Another company, which conducted two studies, was brought in by BC Timber Sales and concluded the marks were natural.

The final opinion, from the B.C. Archaeology Branch, was that, on balance, the marked trees were likely culturally modified.

Five logging deferrals over eight years and the reluctance of contractors to go into the remote, roadless area offered temporary reprieves, but the threat of logging didn’t go away. Then, in a remarkable reversal in February, BC Timber Sales removed the 70-hectare cutblock from the auction block. Combined with road building, logging the block would have taken the heart out of the Dakota Bowl.

A joint news release from the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Nation and the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development said the area “is no longer part of BC Timber Sales operating plan for the Sunshine Coast and it will not be auctioned for harvesting.”

“In recognition of the ongoing cultural importance of the Dakota Bowl area, the Squamish Nation and the province agreed to work together in assessing options that restrict future development or harvesting in this area,” the ministry said in the news release.

ELF’s role was not mentioned. In an email, a forests ministry spokesman attributed the decision to “a collaborative government-to-government decision between the province and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Nation” that was a decade in the making.

The bottom line is the area, which ELF nicknamed the Dakota Bear Sanctuary, is safe, Muirhead said, thanking the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Nation for its stewardship.

“We did it and we did it together,” he said. Even though only a relatively small area was taken off the auction block — the McCrory report recommended at least 450 hectares be protected to preserve biodiversity — Muirhead said it will now be extremely difficult for logging companies to access the area.

“So we don’t perceive any other blocks being proposed within that 450-hectare area,” he said.

The Dakota Bear Sanctuary is not accessible for much of the year, as snow often remains on the ground until summer and bears return in October to den, so ELF makes the most of the few months of access, leading guided hikes to show the unique forest to visitors such as artists, scientists and Squamish Elders.

All visitors are in awe when they spot their first ancient yellow cedar tree and most comment on the peaceful atmosphere of the undisturbed forest, Muirhead said.

“The temperature drops and it’s just calmer. You feel as if you are walking into a living museum with trees that have been standing there for 1,000 years plus.”

“It is an area undisturbed by mountain bikes and ATVs, it is like a time capsule,” Penner added.

The battle to protect the Dakota Bear Sanctuary has inspired groups such as the Living Forest Institute, The Only Animal and Artist Brigade to offer support in innovative ways. T’uy’t’tanat Cease Wyss, Damien Gillis and Olivier Leroux created a geodesic dome with a mix of music and nature sounds and wraparound view of the Dakota Bowl’s ancient forests, which displayed at the North Van Arts gallery, while the Artist Brigade produced art projects and a video.

Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Nation members who have visited the Dakota Bear Sanctuary say the ancient forest and the knowledge that it was used by Indigenous people for hundreds, or possibly thousands, of years offers a remarkable link to the past.

Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Elder Xwechtáal, Dennis Joseph, who accompanied one of the ELF tours of the area, said during the hike that he could feel the spirit of his ancestors.

“This is our sacred home,” he said.

Brian George, 26, a Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Nation member, who works for a Vancouver-based environmental consulting firm, made his first trip to the Dakota Bear Sanctuary in September.

He described the area with the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh words “an kilus,” meaning very beautiful scenery.

“The high-elevation sites are something of a newer archaeological interest,” he said.

It was previously thought Indigenous people historically stayed close to the shoreline, but that is incorrect, George said.

The bark of yellow cedar, found in the high elevation forests, was highly prized for its softness and strength and is believed to have been used for clothing and especially for regalia.

“The Indigenous people were everywhere. The evidence is there and I saw it for myself on some of the [culturally modified trees],” George said.

“They were there during the time of pre-contact and making their mark, harvesting some of the cedar for maybe their clothing, their hats, their baskets. The ancestors were there and they are still there. Those high elevation areas are of great importance because the area is a lot closer to the Creator,” he said, wondering why anyone would consider cutting down such a rich old-growth forest instead of concentrating logging efforts on second-growth.

Cindy Prescott, a University of British Columbia professor in the Department of Forests and Conservation Sciences and a Sunshine Coast resident, also made her first trip to the Dakota Bear Sanctuary in September.

Untouched old-growth forests, in all their complexity, are now rare and the most effective way to protect such areas is for First Nations to be vocal about the need to leave them standing, she said.

“I hope they make it clear to government that they want old forests protected, that they are not okay with the business-as-usual model,” said Prescott, who worries about the increasingly intense logging of old-growth around the Sunshine Coast.

“Our government seems to be living in a past time, before there was a climate crisis and a biodiversity crisis, and we’re managing our forests for one thing only — timber. That is so out of touch with what we now know about the real value of old forests. It’s so out of touch with what we have learned in the last 30 years — it’s shocking,” she said.

Filmmaker Trent Maynard, who is making a documentary about the watershed surrounding Mount Elphinstone, uses 12 wildlife cameras to help illustrate the stories he tells.

The Dakota Bowl is unique because it offers people a chance to reconnect and relearn the history of the land, Maynard said.

“It shows how these forests have been tended for thousands of years before settlement. For me, it’s a real reminder of the damage settlement has done to the Sunshine Coast. It’s a place we can go to think about the original stewardship of these lands. I think a lot of people feel the Squamish history there and they realize there is a lot to be learned from Aboriginal forestry,” he said.

Maynard’s wildlife cameras have picked up bobcats, coyotes, rabbits, cougars and — of course — bears.

McCrory, who conducted the bear den surveys, has worked in some of B.C.’s most spectacular wilderness areas and believes the Dakota Bear Sanctuary is one of the most magical places in the province.

“I have never seen an ancient forest this profound in terms of its aesthetic, biological and First Nations values. It’s littered with culturally modified trees and we found upwards of a dozen black bear dens in the old trees,” McCrory told The Narwhal.

“The history of that area is so incredibly rich that logging those kinds of values would be criminal in my opinion,” he said, adding that he is pleased that, with the help of ELF and the Squamish Nation, BC Timber Sales finally recognized their assessments were off the mark.

Bear dens are usually found at the base of the big yellow cedars, whose centres are prone to rot, creating natural cavities. After a bear has hibernated, the high elevation snowpack provides protection for the mother and cubs, while, in spring, the isolated area, with small hanging lakes and creeks, offers plentiful food for the bruins.

It is not yet known what type of protection will be given to the Dakota Bowl, but possibilities that offer the most protection include an Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area that could come under the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Nation’s Xay Temixw (Sacred Land) land use plan, whose vision is to protect old-growth and wild spirit places.

Other preferred possibilities could be a Class A provincial park or Class A tribal park or ecological reserve, Muirhead said.

The forests ministry said in its email that land use designations under consideration include an old-growth management area, wildlife habitat area or Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Nation area of interest.

“Once a decision is made on the land use designation, the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Nation and the province will collaboratively determine the shape and size of the protected area,” the email said.

Although ELF welcomes any protection, an old-growth management area or wildlife habitat area would not offer full protection as roads, hydroelectric development or commercial recreation tenures could still be allowed, Muirhead noted.

One nagging question for ELF is why BC Timber Sales was so insistent about logging such a special area and whether there are lessons to be learned that will help other efforts to protect at-risk areas on the Sunshine Coast.

Already a battle is shaping up over the Sunshine Coast Community Forest’s plans to log an area in the Trout Lake Forest, within shíshálh (Sechelt) Nation territory. There’s also an ongoing campaign to protect parcels of land that could help connect the three isolated islands that make up Mount Elphinstone Provincial Park.

ELF campaigns and expertise are more important than ever as logging pressures increase around the Sunshine Coast as the population grows, Penner and Muirhead said, noting little of the area is protected.

Only about three per cent of the Sunshine Coast forest district is protected in provincial parks, while about two per cent protected in regional parks. The figures do not include wildlife habitat areas or old-growth management areas.

The province says about 15,400 hectares are available for recreation within the Sunshine Coast Regional District, including 12,300 hectares classified as provincial parks.

But when it comes to old-growth and habitat connectivity, the Sunshine Coast is being short-changed, according to ELF, and an ELF-funded GIS report looking at remaining old-growth in the Howe, Chapman and Sechelt landscape units. The report, completed in December last year by Applied Conservation, shows less than one per cent of old forest remains in some areas in Chapman and Sechelt.

One exception is the Dakota Bear Sanctuary where 37 per cent of the old-growth still stands.

Penner and Muirhead estimate that ELF, a group known for punching above its weight and making its presence felt during land use processes, has won about one-half its campaigns.

It is a pretty good record for such a small group, said Muirhead. But along with the celebration of victories comes the heartbreak of losses, including the Clack Creek forest, which was logged in 2020 despite a local outcry and felt hearts stapled to the trees by community members. It’s a small comfort for Muirhead that ELF succeeded in deferring logging for five years and gained some concessions that protected the best Douglas firs.

Other losses for ELF include the Twist and Shout forest on the slopes of Mount Elphinstone that was logged in 2016, after a two-month roadblock and a dozen arrests. A 2018 report from the Forest Practices Board, B.C.’s forestry watchdog, completed too late to stop the logging, said the area would have been a good candidate for protection because of its rare plants, but noted there are no applicable provincial rules that would have offered protection.

Among ELF’s successes are a 30-hectare site in the Dakota Ridge ancient forest, adjacent to the Dakota cross country ski area. In 2011, following an ELF campaign, it was designated as an old-growth management area. Other victories include the heart-of-the-park campaign, which resulted in the cancellation of logging plans for a BC Timber Sales block adjacent to one of the parcels that makes up Elphinstone Provincial Park in 2018 and the area’s designation as an old-growth management area, the Roberts Creek headwaters ancient forest, containing rare densities of Pacific yews and red cedar, which was protected in 2013 and the Reed Road forest reserve in Gibsons, where logging has been deferred and the areas in question is now part of a long-term planning process.

“We have definitely made the community more aware of us,” Penner said.

Key to the successes are community support and hiring professionals to conduct archaeological and biological assessments for each site.

“The logging agencies do the bare minimum assessments, beyond timber values, so we can expect that they will always miss important details that should be considered,” Muirhead said.

ELF takes a proactive approach by identifying forests of high value that appear on either BC Timber Sales or Sunshine Coast Community Forests’ five year plans. It’s a vital first step, as lack of public input during the early decisions made around site plans is a longstanding issue for community groups, Muirhead said.

ELF then scouts the locations of the cutblocks of interest and, through preliminary field research, decides whether to hire professionals to provide a scientific analysis and examine elements such as ecological or cultural values that appear to be missing from the site plan or when the site plan includes questionable findings.

The next step is public education and fundraising and, as ELF has no overhead costs, all money raised goes to the chosen campaign.

It can take years to get professional reports published, mount public pressure and seek First Nations support, usually through contact with Elders, and that is what makes ELF unique, Muirhead said.

“The strategy is to be doing this research years ahead of a block entering the bidding or contract stage,” he said.

“Many other environmental groups work in a reactionary way -— when logging begins they get mobilized — but, once a contract is signed, the courts will uphold the contract 99 per cent of the time,” he pointed out

Muirhead credited ELF’s unique strategies with helping to save the Dakota Bear Sanctuary from logging.

“However, the journey to get there was filled with dread, confusion, anger, hope, some sacrifice and doubts in the government’s own logging agency — BCTS — to properly manage these great natural gifts provided by intact forest ecosystems.”