‘Afraid of the water’? Life in a city that dumps billions of litres of raw sewage into lakes and rivers

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

How long does it take to become a miner in B.C.? Less than the time it takes for a cup of coffee to get cold.

A reporter with The Narwhal brewed a coffee, then left it on their desk to go pick up a “free miner certificate” at a nearby government office. They filled in a form, handed over $25 and made their way home to find a location for their digital stake on the province’s website. By the time they were navigating the interactive map of claims staked and land up for grabs, their coffee was still hot.

In B.C., anyone 18 years and older who is a Canadian citizen, permanent resident or authorized to work in the country can register and subsequently stake a mineral claim. Individuals need to have their identification verified by a government service desk, as The Narwhal’s reporter did, while corporations — which can also register and stake claims — do not. Once registered and online, if an area of interest is available, you pay $1.75 per hectare for a mineral claim and $5.00 per hectare for a placer claim (which are deposits found close to the surface in loose sand or gravel, for example).

Data obtained by The Narwhal shows after the B.C. government moved the claiming process online, the area staked across the province increased by 70 per cent to 8.3 million hectares and has remained above or around that size over the past 17 years. And whether or not a mine is developed there in the end, these stakes still carry a toll for First Nations, private property owners, waterways and wildlife.

While The Narwhal’s reporter was able to use the tools of the 21st century to (almost) stake a mineral claim, the law that allowed them to do that goes back to the 1850s.

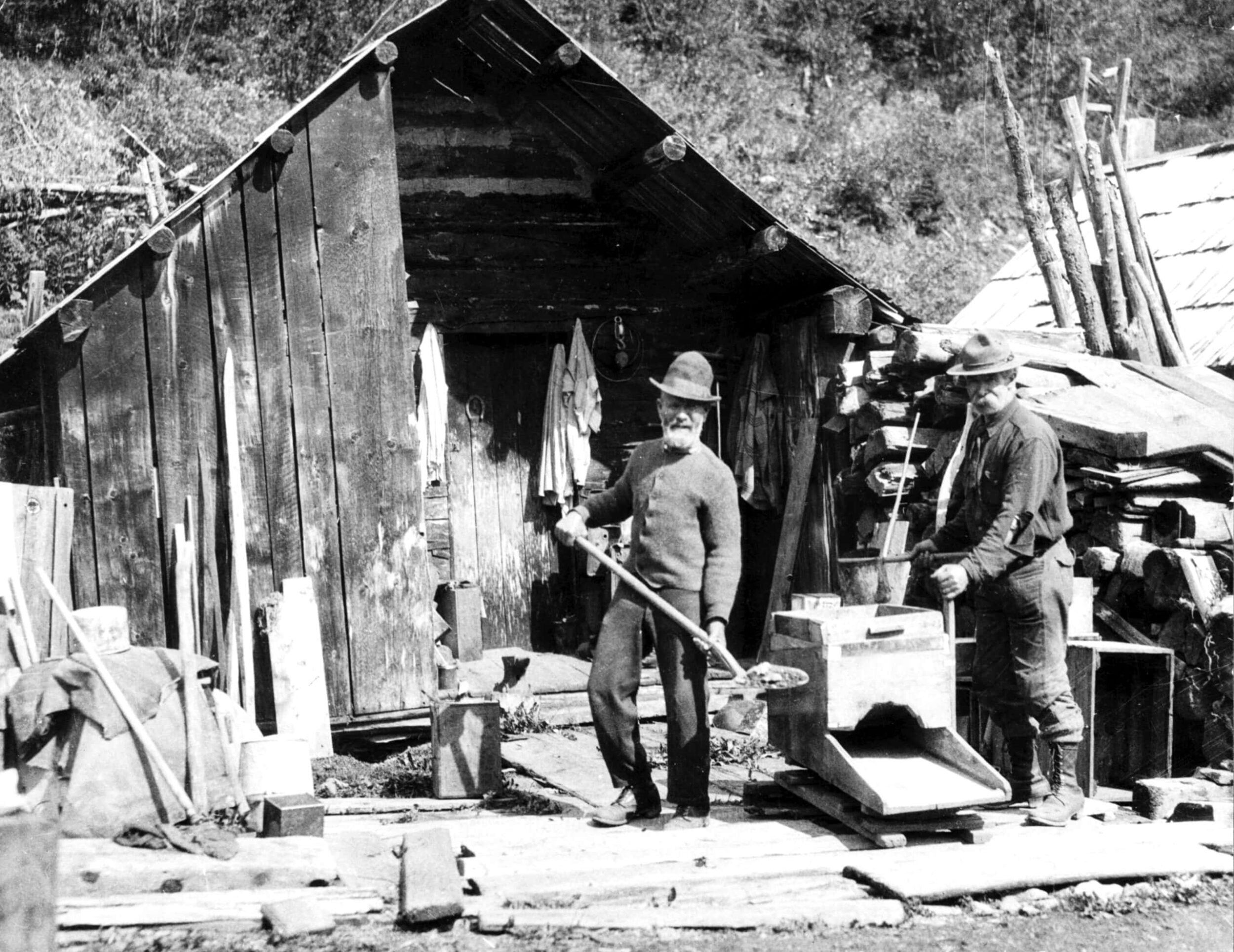

It was the start of the gold rush and B.C. was barely a year old. The law allowed almost anyone to apply for a free miner certificate, giving them the right of free entry to look for minerals on a spot of land they stake. Today’s Mineral Tenure Act is rooted in that same approach and critics say it’s to blame for many historical issues with mining in the province — including infringing on Indigenous Rights, and running roughshod over the environment.

The Mineral Tenure Act “is one of the bedrock foundations of colonization in B.C.” says Naxginkw Tara Marsden, who is from Wilp Gamlakyeltxw of the Gitanyow Huwilp. She has over 20 years of experience working as a consultant on Free, Prior and Informed Consent for land use planning and policy development for First Nations.

During B.C.’s gold rush, settlers were given wooden stakes to claim plots of land for their own, without any negotiations or consent from Indigenous communities. It’s where the phrases “stake a claim” and “stakeholder” come from.

Marsden says the law “paved the way for people from all over the world to come in and access Indigenous lands without consent.”

The speed at which digital claims can be made means the same thing is happening today.

There are few limitations on where someone can make a claim, though some parks, Tsilhqot’in Declared Title Area and treaty settlement lands and reserves are off limits. According to the Ministry of Energy, Mines and Low Carbon Innovation, more than 76 per cent of the province is open to mineral staking.

While other parts of Canada have reformed similar colonial mining laws, B.C. made the process even easier in 2005 when it went online.

“It seems like it’s modernizing the process, but it’s actually making it even easier for people to establish what I would refer to as economic interests in unceded Indigenous lands without even notification to the Indigenous people,” Marsden says.

Moving to the online system was an attempt by the province to revitalize the mining industry. “Mineral Titles Online is just one small part of that whole procedure to bring that confidence back, that gusto, that zest that those miners bring to British Columbia in doing what they do so well; and that’s going out on a huge land base and actually finding minerals,” Richard Neufeld, the former minister of energy and mines, said when the changes were announced in 2004.

Exploration did grow to a huge land base. In the first three years after the process moved online, there was an “exponential” increase in claims, says Nikki Skuce, director of the Northern Confluence Initiative and co-chair of the BC Mining Law Reform network.

The Narwhal obtained data from the Ministry of Energy, Mines and Low Carbon Innovation on mineral and placer titles going back to 1997.

While the number of claims in good standing each year fluctuated alongside the price of minerals, it's the amount of land staked that stands out to Skuce. In the years after the digital upgrade, the total number of hectares claimed jumped from 4.9 million in 2004 to 8.3 million in 2005 and continued to climb to 14.5 million hectares in 2008. That’s an area more than 4.5 times the size of Vancouver Island.

It’s also important to look at specific areas to see where mineral claims are, Skuce says. While the numbers show an overview of the province, there are areas that are likely seeing concentrations of mining claims. Skuce points to the Iskut River Watershed in Tahltan Nation territory as a hotspot for claims. In November 2019, mining tenures took up almost 50 per cent of the watershed.

There are dozens of YouTube how-to videos explaining the simple process. In less than three minutes YouTuber Canadian Gold Mining finds a spot and signs off with, “that’s it. Hit next and it’s yours!” User meMiner explains in a 12-minute video tutorial for finding and staking a gold claim, “I wanted to have a claim in B.C., so when I go out to B.C. this summer I don’t have to ask permissions.”

Once someone has a free miner certificate and stakes a claim, they have the right to access the area for “exploration and development.” That could mean using metal detectors, handheld tools to dig trenches or pits, or even setting up a temporary camp, according to the province’s policy on “permissible activities.”

But no work is necessary to keep the claim, explains Gavin Smith, staff lawyer with West Coast Environmental Law. “When you obtain the mineral claim, it has a one-year expiry, but you can indefinitely renew the mineral claim for as long as you want.” In order to keep the claim, you can either work it and register your efforts with the government, or pay a fee of between $10 and $40 per hectare in lieu of work.

There are a few restrictions on claim holders, including: they can’t access orchard land or “land under cultivation,” heritage properties or an area within 75 metres of a residence. However, the restrictions don’t stop someone from claiming mineral title on these lands, private property or even, “underneath someone’s house,” Smith says. “It's not that you haven't staked a claim there,” Smith says. “You actually do technically own the minerals under their house. You just have statutory or legal restrictions on what you can access.”

And once someone stakes a claim, they have the exclusive right to the minerals over everyone else, says Calvin Sandborn, Senior Counsel at the Environmental Law Centre at the Faculty of Law, University of Victoria.

Indigenous communities and rural property owners are facing the brunt of B.C.’s outdated mining law.

In 2012, two individuals staked claims all over North and South Pender Island, including on private property.

“The outrageousness of mineral staking on rural residential and agricultural lands in the Gulf Islands has the potential to bring home to the broader public and decision-makers that the time for modernizing the Mineral Tenure Act has come,” wrote Jessica Clogg, Executive Director & Senior Counsel of West Coast Environmental Law, at the time.

In 2017, a group of First Nations women turned the tables by staking a claim on then-minister of energy and mines Bill Bennett’s property. “We wanted to show how ridiculously easy it is to stake a claim on someone’s land. This should give politicians and all British Columbians an idea of how unfair the process is,” said Bev Sellars, chair of First Nations Women Advocating Responsible Mining, in a press release. Bennett responded lightly at the time that he got the message but, “there is nothing to be found there. They’ve made a bad investment.”

Sellars says she let the claim expire after a year. Looking back, she told The Narwhal, “we made our point and we hoped that would be enough — but obviously it wasn’t.”

The staking certainly didn’t stop there. In 2019, “Marie Reimer and Doug Hallat were sitting outside, having a drink, when a man drove up and notified the couple he had papers staking a claim to mineral beneath their property’s soil,” according to Kamloops This Week. The Kamloops couple was also left calling for reform.

Beyond the possible intrusion into private property, “it’s contrary to rational land use planning because you can stake these claims in sensitive watersheds and areas that are environmentally sensitive,” Sandborn says.

While they never ended up staking a claim, The Narwhal’s reporter scoped an area the province considered fair game for prospectors. It was on unceded Indigenous territory, unlikely to have any significant mineral resources and included wetlands and a creek that feeds into a salmon river. Since the reporter first looked at the spot and reached out to the Indigenous community in 2021, a Vancouver-based exploration company staked the area and hundreds of surrounding hectares.

“It's pretty egregious that you don't have to ask permission from anybody to go stake and get rights on land, to go explore and potentially open a big mine,” Skuce says.

Kendra Johnston, president of the Association for Mineral Exploration B.C., says only one in 10,000 exploration projects will ever become a mine.

“On average, there are 250 to 300 exploration projects active across the province each year. The hope and intent to find a deposit that is economically and socially viable to be developed into a mine lies at the heart of any exploration investment. But finding a viable deposit is not easy and takes significant risk capital. Discoveries that are capable of becoming a mine are rare and special finds.”

But the process of staking can still be the source of many conflicts, Skuce says. Communities have different land use priorities or values for the area but anyone with a mining title can get in the way.

In 2016, the Gitanyow learned that warming temperatures in the Meziadin watershed were altering the habitat of sockeye populations. As protected creeks where they had traditionally spawned became too warm, fish were found in creeks where rapid glacial melting kept water temperatures down. But those creeks were unprotected, and as the glaciers retreated, new areas were exposed, enticing prospectors to stake claims above the salmon watershed. This put both the unprotected creeks and the fish at risk.

Gitanyow wanted to expand their existing conservancy in the area but the process was stalled because of multiple mining tenures on the land.

“We haven't ever been notified, we haven't ever consented to any of these mineral tenures,” Marsden says, adding that the only way to change this is through reforming the Mineral Tenure Act.

Last August, the hereditary chiefs decided not to wait for the provincial government and declared creation of the Wilp Wii Litsxw Meziadin Indigenous Protected Area.

The current B.C. government has promised reform. In 2022 it published the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act Action Plan. Action 214 commits the Ministry of Energy, Mines and Low Carbon Innovation to “Modernize the Mineral Tenure Act in consultation and co-operation with First Nations and First Nations organizations.”

The ministry declined an interview request from The Narwhal.

B.C. has been particularly slow to change its process for granting mineral titles. For years there has been report after report and ongoing calls to change this law. The long-held identity of B.C. as a “gold-rush province” and the “disproportionate amount of political power in the hands of the mining industry,” has held reform back, Sandborn says.

Other jurisdictions have moved away from the free entry system and either added the consent of private property owners and Indigenous peoples or excluded mining claims in certain areas, Sandborn says. He adds B.C. should follow those examples.

In Ontario, for example, amendments were made to mining laws in 2012 to require consultation with First Nations. Anyone seeking to make a claim also has to take an online course intended to “raise awareness of the importance of considering other users of public land.”

In Quebec, municipalities and regional governments can set “no-go zones” in land use plans. Property owners also have to give consent before any exploration work is done on their land.

Similar to B.C., the Yukon adheres to a free entry system that has been heavily criticized by conservationists and First Nations. In 2012, the Court of Appeal of Yukon ruled the government has a duty to notify, consult and accommodate the Ross River Dena before any mining exploration happens in their territory. As the Yukon Government works to update its mining laws, Carcross/Tagish First Nation, for one, has called for the free entry system to be abolished.

Skuce believes would-be mineral titleholders should be required to meaningfully engage and get permission from Indigenous communities and private property owners before they get any legal rights. “We also need to update the policies for compensating people for areas that are staked,” she says.

A current legal challenge in B.C. could set the precedent for reform. In 2021, the Gitxaała Nation filed a legal review of seven mineral claims granted in their territory, without any consultation, between 2018 and 2020 . The Mineral Tenure Act is, “inconsistent with the United Nations Declarations on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which B.C. has affirmed in the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (DRIPA),” a Gitxaała legal backgrounder states.

“A fundamental shift is possible,” Marsden says, “because we have land use plans in place. Most nations are in the process of developing them if they don't have them already. We have a foundation to build from.” The Gitanyow Lax’yip land use plan includes ways to work with the forestry industry, including the use of special management zones and areas that have to be avoided, Marsden says.

“It's not scary, or the end of the world,” she says. “We have forestry operating, surviving fine with the land use plan. So why can't mining be the same?”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

Break out the champagne: Emma’s storied life and leadership in journalism has earned her the...