Rocky Mountain coal mine in Alberta takes next step to expansion

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

Plans for new logging in endangered caribou habitat threaten to undermine hard-fought population gains for a struggling herd, warns a Kootenay-based conservation group as the province considers two logging proposals.

Earlier this year, wood product companies Stella-Jones and Pacific Woodtech submitted plans to log in the Seymour River watershed, northwest of Revelstoke, B.C. The area, which includes rare old-growth inland temperate rainforest, offers crucial habitat for the Columbia North caribou herd.

Eddie Petryshen, a conservation specialist with the organization Wildsight, worries new logging will put the Columbia North population at greater risk of extinction at a time of renewed hope for its recovery. The herd, down to roughly 130 animals in 2004, now has about 210 caribou.

“We know as industrial disturbance increases, these caribou populations decline,” Petryshen told The Narwhal in an interview. “We need to start looking out for their needs and it certainly isn’t another 600 hectares in their core habitat being logged.”

In July, Petryshen visited several areas, known as cutblocks, the companies plan to log in the coming years. He found forests that had never been logged — younger stands that had regrown after wildfires and “beautiful valley bottom old growth” where some trees measured one-and-a half-metres in diametre.

In one of Pacific Woodtech’s proposed cutblocks in the upper Seymour, Petryshen found a heavily travelled wildlife trail and caribou droppings.

“It’s core caribou habitat,” he said. “You don’t want disturbance in those areas.”

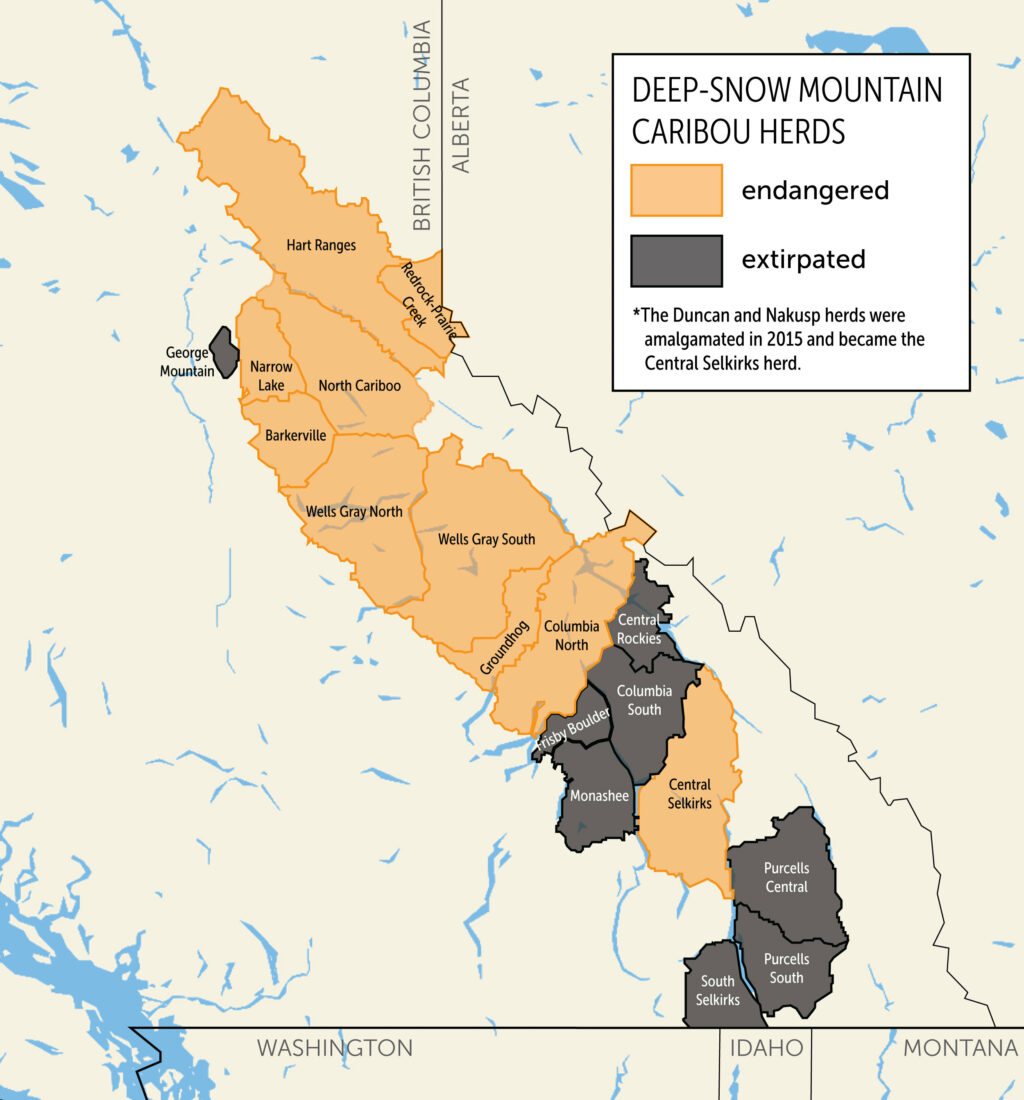

Some southern mountain caribou herds have already been wiped from the B.C. mountain ranges they once called home. In 2014, the federal government released a recovery strategy that aimed to achieve self-sustaining caribou populations large enough to support First Nations harvesting. But more herds have been lost since then.

While southern mountain caribou are listed as threatened under Canada’s Species At Risk Act, the scientific committee that advises the government on the status of at-risk species determined the southern group of herds, including Columbia North, are endangered.

These deep-snow caribou, found only in Canada, rely on layers of snow each winter to reach the scraggly hair lichens that hang from old trees.

In 2018, the federal environment minister determined southern mountain caribou faced imminent threats to their recovery. As required under the Species at Risk Act, the minister recommended the federal government issue a rarely used emergency order to protect the caribou.

An emergency order would allow Ottawa to make decisions that typically fall to provincial governments, such as whether to issue logging permits. But the federal cabinet chose not to issue the order, opting for a more collaborative approach.

When Petryshen heard earlier this summer that Environment and Climate Change Canada Minister Steven Guilbeault had recommended an emergency order to protect caribou in Quebec, his mind immediately went to the deep-snow caribou in B.C. “A lot of the same issues apply here,” he said.

Nowhere near enough of the Columbia North herd’s habitat is protected, Petryshen warned.

“We are losing it as we speak,” he said.

The Columbia North caribou herd’s range spans more than 4,600 square kilometres, stretching northeast from Shuswap Lake in the southern Interior region of B.C. across several mountain ranges to the Rockies.

“It’s a massive area,” Petryshen said, describing old-growth cedar and hemlock forests scattered in valley bottoms, the “super rugged” terrain of the North Columbia mountains and the “long, rolling ridge lines” of the lower elevation Seymour Mountain range.

The Columbia North herd and several neighbouring herds are unique among southern mountain caribou populations because they spend more time at lower elevations during certain seasons, biologist Rob Serrouya, co-director of the Wildlife Science Centre for Biodiversity Pathways, exlained in an interview.

In practice, that means the overlap between the herd’s habitat and “valuable timber is much more pronounced,” he said.

The areas Stella-Jones and Pacific Woodtech have proposed to log fall within core habitat for Columbia North caribou — areas where a 2014 federal recovery strategy said there should be minimal disturbance, a spokesperson for Guilbeault noted in a statement to The Narwhal.

Stella-Jones is a major North American supplier of pressure-treated lumber and produces utility poles at its southern B.C. mills. In its proposal, the company lays out plans to log more than 300 hectares of forest, including old-growth trees, in the Seymour River watershed between 2024 and 2027.

In an emailed statement to The Narwhal, a spokesperson for Stella-Jones said the company “is currently in the preliminary stages of creating a final operational plan for harvesting activity in this area.”

Stella-Jones is engaging with First Nations and other stakeholders on wildlife management, and “remains committed to responsible harvesting practices,” the statement said.

Pacific Woodtech produces laminated veneer lumber products at its Golden, B.C., mill. The company took over the Golden mill from Louisiana-Pacific two years ago. While Louisiana-Pacific is listed as the proponent on the recent logging proposals, which outline harvesting plans in the area for 2024 to 2029, Pacific Woodtech has applied to the B.C. government to have the pertinent forestry licenses and associated road permits transferred over.

Pacific Woodtech did not respond to The Narwhal’s request for comment by publication time.

A spokesperson for B.C.’s Ministry of Forests said the government has received Pacific Woodtech’s request to take over Louisiana-Pacific’s forest tenures. Before a decision is made, the province will consult with First Nations and review potential impacts on community, environmental, economic and business values, the spokesperson said.

The B.C. government also has yet to decide whether to allow the two companies’ logging proposals to proceed.

The spokesperson for Guilbuealt said the federal government “believes that a collaborative approach is the best way to address threats to species at risk.” But added that “Environment and Climate Change Canada encourages partners to adapt practices in a manner consistent with recovery objectives.”

Serrouya said the biggest successes for caribou he’s seen over his career are the result of collaborations between governments, First Nations and industry.

But “forestry right in core critical [habitat] does increase predation risk to caribou. There’s no way to sugarcoat that,” he said.

While caribou evolved to rely on old forests, the shrubs and herbaceous plants that flourish after logging offer more attractive habitat for moose and deer.

As moose and deer populations grow, they attract wolves and cougars, Serrouya explained.

For struggling caribou herds, this increase in predators on the landscape can be disastrous.

By the mid-1990s, logging had dramatically changed the dynamics between predator and prey in the Columbia North herd’s habitat and the population was in steep decline.

Then things started to change. A land-use planning process in the 1990s led to new protections, which helped slow the pace of logging in the herd’s core habitat.

In the early 2000s, the B.C. government also started giving out more moose hunting tags targeting adult females. Within a few years, moose numbers declined by about 70 per cent, Mateen Hessami, a community-based wildlife ecologist with Biodiversity Pathways, said in an interview.

As moose numbers fell, wolves dispersed across the landscape. With fewer predators in their core habitat, the caribou population began to stabilize, he explained.

The provincial government also culls wolves in the herd’s range each year — but Hessami said fewer wolves are killed in the Columbia North herd’s habitat compared to other caribou ranges because of the moose management program.

The program has also benefited hunters, who can fill their freezers while supporting caribou recovery, Hessami, who studied the moose reduction program as part of his graduate research, explained.

At the same time, Serrouya said, “some measures of habitat were improving.”

Habitat protections helped stem the decline of old forests, Serrouya said, and the young forests that attracted moose to the area started to age. As the trees grew taller and the canopies closed, the shrubs and herbaceous plants moose prefer to eat dwindled. For caribou, it meant the habitat they’d lost was starting to recover.

But Petryshen warned each new cutblock or road carved into endangered caribou habitat locks in decades of predator control.

“I think the public needs to know that and understand that’s the trade-off that the province is apparently making to continue to subsidize the forest industry,” he said.

Hessami’s modelling suggests if all logging in Columbia North core habitat stopped today, the forests would likely recover enough by about 2040 that there would be little need to kill wolves in the area. The herd would be self-sustaining.

In a statement to The Narwhal, a spokesperson for B.C.’s Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship said the province has “long acknowledged that habitat protection, restoration and management are crucial for caribou recovery.”

B.C.’s caribou recovery program is engaging with First Nations to set habitat objectives for the Columbia North herd “to ensure that caribou have a pathway to reaching self-sustaining populations,” the spokesperson said.

What that means for Stella-Jones and Pacific Woodtech’s proposals remains to be seen. A spokesperson for the Ministry of Forests couldn’t provide a timeline for making a decision about the logging plans, but said risks to caribou would be thoroughly analyzed.

For Petryshen, the answer is clear. With caribou populations under immense pressure, he’s calling for a moratorium on logging in core caribou habitat.

“The situation is dire,” he said, “we’ve got to stop pretending that we’re adequately protecting habitat while it’s continuing to be logged.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...