In a Nova Scotia research lab, the last hope for an ancient fish species

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...

In the heart of B.C.’s Cariboo region lies an old-growth rainforest valley untouched by industrial logging or road building. Salmon and trout spawn in a glacier-fed river bounded by wetlands. Caribou, grizzly bears and wolverines roam among cedar and hemlock trees hundreds of years old. Settlers called the valley Raush, an abbreviation of Rivière au Shuswap, referring to the Secwépemc peoples whose name they struggled to pronounce.

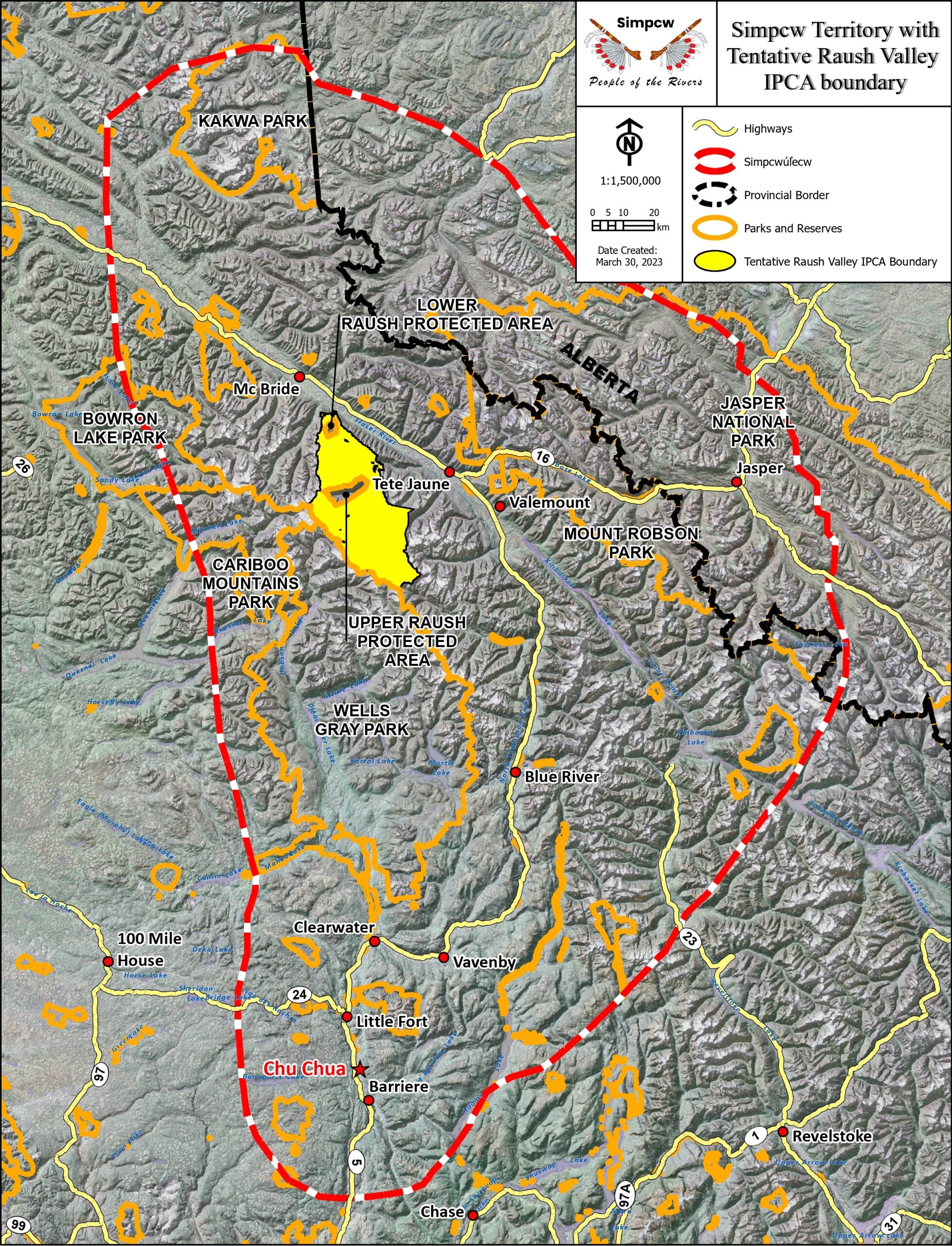

This week, two years after local ranchers and loggers objected to clear-cutting plans for the valley, the Simpcw First Nation declared the Raush River watershed an Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area (IPCA), signalling their intention to protect the valley and exercise their right to control what happens there.

“The area has had little resource development, and we intend to conserve it,” George Lampreau, Kúkwpi7 (Chief) for Simpcw stated. “Protecting the Raush as an IPCA allows us to continue to yecwmenúĺecw (take care of the land) as we have for time immemorial.”

The Raush, ringed by the snow-tipped northern Columbia Mountains, is the largest undeveloped, unprotected watershed in southern B.C. It’s part of the province’s vanishing inland temperate rainforest that scientists warn is nearing a state of ecological collapse following decades of industrial logging.

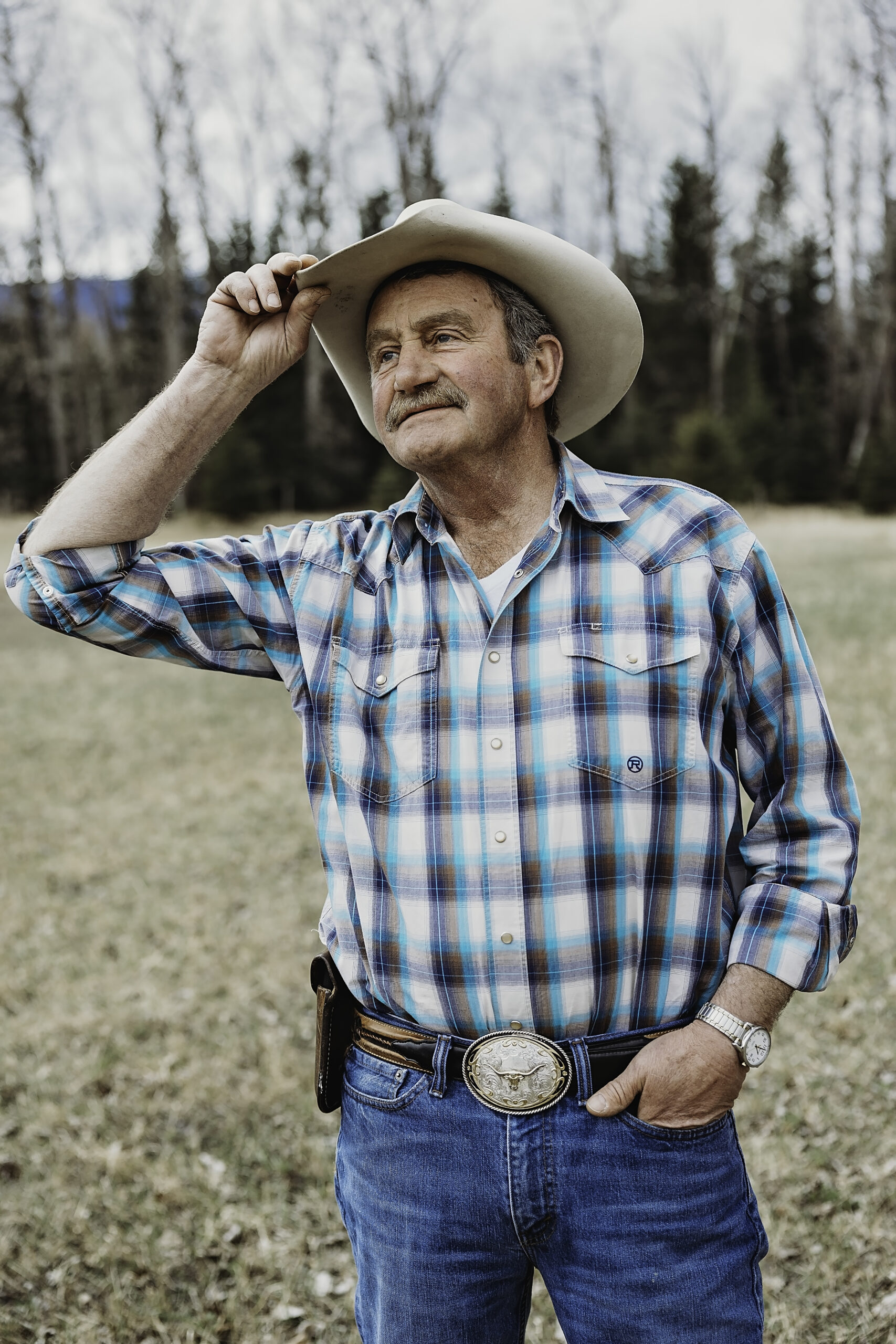

Speaking to The Narwhal, Lampreau recalled being awestruck by the crystal clear Raush River as he and others flew in a helicopter in the fall of 2021, entering the sizeable valley from the southwest where it connects with Wells Gray Provincial Park in an important provincial wildlife corridor.

“It is totally amazing,” he said. “It’s something to see a landscape that does not have a cut block or road in there, other than probably some historical trails or First Nations trails through the valley that were along the river for access. It’s untouched and pristine and it is so beautiful.”

The newly-declared area surrounds two existing provincial protected areas. Together, the two protected areas, called the Upper Raush and the Lower Raush, cover about one-fifteenth of the 100,000-hectare watershed. Most of the valley, spread out between the two protected areas, remains open to industrial logging.

Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas are gaining recognition worldwide for their role in preserving biodiversity and securing a space where communities can actively practice Indigenous ways of life. A number of First Nations in B.C., including the Gitanyow, have declared protected areas without support from the B.C. government, serving notice that Indigenous people remain the true stewards of their lands. Lampreau said the Raush declaration puts the province on notice that “this is a direction we’re going to go with that area, and we will be the decision-makers when it comes to land-use planning in our territory.”

In emailed response to questions, the Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship said the government is aware of the declaration and acknowledges the efforts of the Simpcw and other First Nations to protect ecosystems within their territories and “care for the water, land, animals and other natural resources that their communities have relied on for millennia.”

“Our government welcomes the opportunity to work with First Nations to better understand and share our collective perspectives and to jointly develop an approach to land stewardship.”

Lampreau said the nation has been left out of decisions about the valley before. “We had some issues around some potential logging in there that we felt we weren’t properly consulted on and weren’t going to get consulted on,” he said, referring to a statement the Simpcw made in 2021 after news surfaced about plans to clear-cut in the Raush. The nation said it did not support cutting permit applications and that adequate consultation had not occurred. “So, we decided to take this route and put conservation measures on there, so it’s protected. It will be a park that Simpcw will take the lead on, with participation from the local valley residents on how we move forward.”

Carrier Forest Products Ltd., a B.C.-based company with mills in Prince George and Saskatchewan, holds logging rights to the Raush. But Carrier would only be able to gain easy access to Raush Valley forests through private ranch land or by building a logging road through the Lower Raush Protected Area.

Over the past two years, Carrier has clear-cut to the protected area boundary. The provincial government confirmed BC Parks had initial discussions with Carrier Lumber in 2021 to provide information about “steps that would be required to apply for an investigative use permit for a proposal to build a road through the protected area,” adding that Carrier Lumber has not applied for an investigative use permit at this time.

In an email, Carrier president Bill Kordyban told The Narwhal he will defer all responses to questions about logging in the Raush Valley to Lampreau. Lampreau said the nation has a good relationship with Carrier, despite some issues in the past, and “they’re on board with our idea to protect the Raush.”

Other land that could also be used to access timber in the Raush is owned by several generations of Rodger Peterson’s family, who have ranched on the valley’s outskirts since the 1960s. “Carrier and different logging companies over the years have talked to us about going there,” Peterson said in an interview. “And it hasn’t happened. And if I or my family has anything to say about it, it’s not going to.”

Peterson said he’s pleased with the Simpcw declaration, calling it “a step in the right direction not to have that valley devastated.”

“It’s hard to describe the sense of peace and tranquility when you’re in that valley,” he said. “It’s reality at its best … Anything can be destroyed. But it’s hard to save something. That’s where I’m at.”

Michelle Connolly, director of Conservation North, a Prince George science-based group that advocates for nature in central and northern B.C., congratulated the Simpcw Nation on the declaration.

Connolly said the science is clear that industrial logging and road building in forests that have never been logged is incompatible with preserving biodiversity. “In this part of B.C., the winters are harsh, the snow is deep, food is scarce and it’s these old-growth forests that the wildlife needs to get them through winter,” she said, pointing to caribou, which rely on old-growth forest lichens, as one example. “That’s what the Raush has to offer. And valleys like the Raush are almost all gone.” Only two other valleys in the upper Fraser headwaters — the Goat and the Walker, the other “jewels in the crown of the inland temperate rainforest” — remain intact.

Connolly hopes the entire Raush Valley will continue to be off limits to logging and road building to protect wildlife habitat. “The thing that’s protected the Raush is the fact that access is limited. That’s really kept poachers out. That’s kept motorized activity out of the valley. And really importantly, it’s kept industrial logging out of the valley.”

Roy Howard, president of the Fraser Headwaters Alliance, which has been advocating for Raush Valley protection for more than 25 years, said alliance members are overjoyed the Simpcw have declared the Raush an Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area. Howard described the valley as a “big intact wilderness” where iconic species like caribou, moose and grizzly bear can roam unharmed by poachers who gain access to other remote valleys via logging roads.

Lampreau said the Simpcw are in the very early planning stages for the protected area and will be consulting with nearby residents, local mayors and groups like the Fraser Headwaters Alliance. “We’re going to work with everybody in the valley so that all of our needs are met. We’ll be the leaders on this, but they’re going to be involved in planning.”

The Simpcw will examine eco-tourism options and are unlikely to consider logging unless there is a forest health issue that needs to be managed, the chief said. “We’re working closely with Carrier on land use planning and logging practices within the valley in order to do a better job.”

The Simpcw have six directives industry must follow on their territory, the chief noted. At the top of the list is water. “For us, water is life. We come from water. We’re born in water in the womb. It’s sacred to us. So, we protect it.”

He said the nation requires any industry operating in its territory to exceed provincial guidelines. “For example, if they have 25 metres [set back from] a creek for protection, we want 50.” Other directives aim to protect medicinal plants, cultural use, wildlife, archeological sites and Simpcw peoples.

Last December, the B.C. government committed to protect 30 per cent of the province’s land by 2030, joining global efforts to safeguard nature and reverse biodiversity loss. The commitment to double B.C.’s current land protections was made in Premier David Eby’s mandate letter to Nathan Cullen, Minister of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship.

“We have seen the impacts of short-term thinking on the British Columbia land base — exhausted forests, poisoned water and contaminated sites,” Eby’s letter stated. “These impacts don’t just cost the public money to clean up and rehabilitate, they threaten the ability of entire communities to thrive and succeed.”

The letter instructed Cullen to work with Indigenous communities to reach the 2030 protection goal, including through the creation of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas. “By planning carefully, we can ensure our province enjoys the best of economic development while conserving wild spaces,” Eby said. “Indigenous partners in this critical work can bring their expertise, knowledge and priorities to the table to ensure this effort lasts for generations.”

A briefing note for Cullen described Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas as “largely conservation-focused areas” identified by First Nations that “may include some industrial use.”

In its email, the Resource Stewardship Ministry said it’s committed to working with First Nations on a co-managed approach to land and resource management and looks forward to continued discussions with the Simpcw. “Where possible, our preferred approach is for Indigenous-led stewardship interests, such as IPCAs, to be addressed through government-to-government collaborative processes like modernized land use planning. This ensures that economic, environmental, social and cultural values are considered, that collaborative processes can be built with First Nations and that robust engagement can be undertaken with stakeholders, local government and the public.”

The ministry confirmed there are old-growth deferral areas in the Raush but said it cannot share the locations because it is respecting the confidentiality of government-to-government engagements with First Nations. “If we were to publish details of areas that are deferred/not deferred, this would result in the responses of individual First Nations being disclosed without their consent.”

The two-year deferral areas were instituted in November 2021, following an old-growth strategic review that recommended the B.C. government defer development in old forests “where ecosystems are at very high and near-term risk of irreversible biodiversity loss.” The B.C. government subsequently deferred logging in 2.6 million hectares, pending consultations with First Nations.

Lampreau said the nation has met with B.C. government representatives and hopes the Raush Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area will soon be enshrined in legislation. “Creating an IPCA in the Raush Valley is our long-term commitment to conserve lands and waters for future generations.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...

From investigative reporting to stunning photography, we’ve been recognized with four 2024 CAJ Awards nods...

The Narwhal is expanding its reach on video platforms like YouTube and TikTok. First up?...