Hope for a huge, ancient and imperilled fish

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

In the face of widespread public backlash, the Alberta government agreed to rethink its plan to open parts of the Rocky Mountains and foothills to open-pit coal mining — but it’s a different story just across the provincial border, where an already massive industry could get bigger.

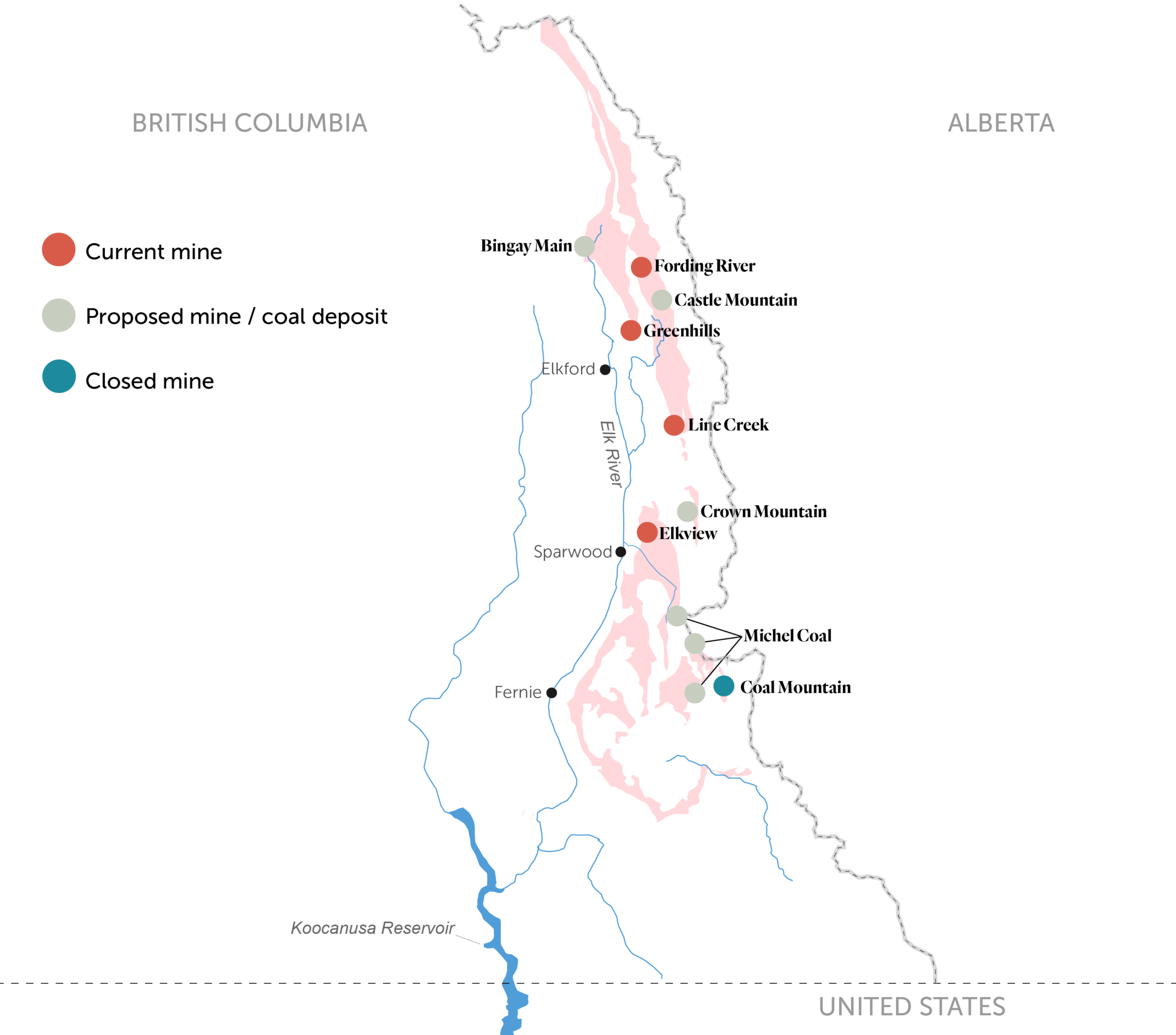

Coal is British Columbia’s most valuable mined commodity: the provincial government forecast production to be worth almost $4 billion in 2020. Eighty-three per cent of that production took place in the Kootenay Rockies, where Teck Resources operates four metallurgical coal mines.

Though Teck is a major employer and economic contributor in the region, its mines are also a persistent source of selenium pollution. Some conservationists fear the problem could worsen if any of the four proposed coal mines in the area are built.

Elevated levels of selenium can cause deformities and reproductive failure in fish. The adult population of a trout species downstream of Teck’s mines recently saw its numbers fall 93 per cent. The cause of the collapse remains under investigation.

Farther north, in the foothills of the Rockies in the Peace region, Conuma Coal Resources operates the province’s other three metallurgical coal mines (metallurgical coal is used in the steelmaking process). Decades of industrial development in the area has taken a toll on wildlife and a proposed mine is prompting concerns about increased risk to endangered caribou.

Here’s what you need to know about the five proposed coal projects in B.C.’s Rockies.

Teck has put forward a proposal to mine metallurgical coal from Castle Mountain, just south of the company’s existing Fording River operations. If the project is approved, Teck expects all coal processed at Fording River — 10 million tonnes a year — would come from the Castle Mountain mine by 2030, extending the life of the Fording River operations by several decades, according to the initial project description.

The project is in the early engagement stage of a coordinated provincial and federal assessment process and Teck is now working on a detailed project description.

Chris Stannell, Teck’s public relations manager, said in a statement to The Narwhal that the company’s Fording River operation employs about 1,400 people and the project would “provide for continuing socioeconomic benefits” for the region.

But in public comments, numerous concerns have been raised about impacts on air quality, increased selenium and nitrate contamination of local waterways, greenhouse gas emissions, impacts on First Nations’ use of the land, the loss of biodiversity and more.

Four companies are proposing new coal mines in the Kootenay Rockies. Conservationists fear increased pollution in the region if they are approved. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Teck is building additional water treatment plants to reduce the amount of selenium pollution from its existing mines and Stannell said the company would develop a plan to mitigate water quality impacts from the extension project. But Lars Sander-Green, mining lead with the Kootenay-based conservation organization Wildsight, questioned the long-term feasibility of the company’s plan and said Teck should focus on addressing selenium pollution from its existing mines.

Sander-Green also noted concerns about impacts on local bighorn sheep, adding that the mining project “would be basically taking down a mountain over the next four to five decades.”

Bighorn sheep in the Elk Valley east of the Elk River “winter at high elevation on south- and west-facing windswept, sunbaked slopes,” Kim Poole, a wildlife biologist at Aurora Wildlife Research and the main author of the Kootenay region bighorn sheep management plan, told The Narwhal.

Teck Resources already operates four metallurgical coal mines in the Rockies using methods that have completely changed the landscape of the mountains, as seen here. Photo: Callum Gunn

There’s very little snow in these high elevation grassland areas, which means the sheep are able to forage in the winter, he said. But these winter ranges are limited.

Poole said Teck’s reclamation of mined areas over the past few decades has helped bolster the sheep population, but the company can’t reclaim high elevation ranges once the mountaintop has been removed

The long-term implications for the sheep aren’t clear, Poole said.

It “may not have a great impact at the population level, but it probably will have some impact at the more local sub-population level,” he said.

North Coal Limited, a Canadian subsidiary of the Australian company North Coal Pty Ltd., is proposing the Michel Coal Project, a mine in the Crowsnest coalfield, about 15 kilometres southeast of Sparwood. If the project is approved, it would produce between 2.3 million and four million tonnes of raw coal over a 30-year mine life.

As with other existing and proposed coal mines in the Elk Valley, water pollution is a key concern for local conservationists.

“The current cumulative water quality impacts of the existing Elk Valley coal mines clearly preclude any additional mines within the watershed,” Wildsight wrote in public comments in August 2019.

A river near B.C.’s scenic Elk Valley where Teck’s coal mines have led to a decades-long selenium pollution problem. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

Patty Vadnais, North Coal’s manager of social responsibility and external relations, said in a statement that the project “is designed to achieve the objectives of the Elk Valley water quality plan.” The company plans to “address selenium and other elements of concern at the source by using a unique combination of features that together will prevent contamination,” Vadnais said.

Alongside active water treatment facilities, North Coal says on its website that it would also employ passive water treatment options such as saturated rock fills — essentially using flooded pits filled with waste rock to remove selenium.

Teck has employed saturated rock fills as part of its water treatment plan and says it has seen success from its first facility. But Sander-Green said in an email to The Narwhal that Wildsight is “concerned that technology is new and unproven,” raising questions about who would manage and monitor the rock fills after a mine closes down.

In its 2019 comments, Wildsight also noted the importance of the Michel Creek watershed for wildlife: “Wide ranging carnivores like grizzly bears, wolverine and lynx rely on the health and function of the Michel Creek for connectivity.”

The North Coal project is in the “pre-application” phase of the provincial review process. Vadnais said the company plans to submit its project application to the federal and provincial governments in the coming months.

Vancouver-based Centermount Coal Ltd. has proposed the Bingay Main Coal Project about 21 kilometres north of Elkford.

If the project proceeds, it’s expected to operate for between 12 and 14 years and produce one million tonnes of coal per year.

Elkford residents raised numerous concerns about the project, including its potential impacts on recreation, water and wildlife, The Free Press newspaper in Fernie reported in 2018.

In 2017, there were 250 public comments on issues including fish habitat, water quality, air quality, employment, community infrastructure, recreation and community wellbeing, with many expressing strong opposition to the project.

According to a status update provided to The Narwhal by B.C.’s Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy, the project is in the pre-application phase of the provincial assessment process and hasn’t been active since 2018. However, last year, the company asked the provincial environmental assessment office to keep the project in the process, according to a recent coal industry overview produced by the Ministry of Energy, Mines, and Low Carbon Innovation.

Another Australian company’s Canadian subsidiary is behind the Crown Mountain Coal Project, a proposed open-pit mine about 12 kilometres northeast of Sparwood. NWP Coal Canada Ltd., which is owned by Jameson Resources Limited, expects the project would produce about 3.7 million tonnes of coal per year over a 16-year mine life.

Early public comments, collected in 2016 through the provincial environmental assessment process, raised concerns about impacts on grizzly bear, moose and sheep habitat, backcountry recreation and water quality.

According to the provincial government’s recent coal industry overview, NWP Coal continued work last year on its environmental assessment application and conducted baseline environmental surveys.

The company is now in the process of drafting its application for an environmental assessment certificate and plans to submit this year, according to the status update from the provincial environment ministry. The project is also subject to the federal impact assessment process.

Selenium pollution remains a pressing concern for all new mines under consideration in the Kootenay Rockies.

“Fundamentally, every new mine proposal on both sides of the Rockies is promising they’ll solve the water pollution problem with some combination of saturated rock fill, waste rock dump construction techniques, water treatment facilities, wetlands, source control, geotechnical covers and so on,” Sander-Green said in an email.

“But Teck has spent many hundreds of millions trying to deal with their water pollution problem and they haven’t made much progress and have missed many targets in their water treatment plans. It seems unlikely that a new company is going to be able to solve all these problems from day one,” he said.

Sander-Green said there is also growing unease around other water contaminants, including nitrate, nickel and calcite.

In some areas of the Elk Valley, “the stream bed is basically turning into concrete from the calcium coming out of these mines,” Sander-Green said in an interview with The Narwhal.

Selenium pollution in the Kootenay Rockies is a danger to westslope cutthroat trout, which rely on stream beds in the Elk Valley. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

That’s a problem for westslope cutthroat trout, which lay their eggs in gravel nests, he explained. When the stream bed solidifies, these fish can’t properly protect their eggs.

Sander-Green said it’s crucial to consider the cumulative impacts of mining in the Elk Valley.

“What’s going to happen in 100 years? How are we going to deal with these problems?” he said.

All four proposed projects fall within the traditional territory of Ktunaxa Nation. In a statement to The Narwhal, Kathryn Teneese, Chair of Ktunaxa Nation Council, said: “The Ktunaxa Nation, as the proper Title and Rights holder in Qukin ʔamakʔis, is deeply involved with industry and other governments in the review and decision making regarding existing and proposed coal mines and the rehabilitation of the land and waters.”

Glencore Canada’s proposed Sukunka Coal Mine would be located about 55 kilometres south of Chetwynd in Treaty 8 territory in northeast B.C., in a critical habitat of an endangered caribou herd.

If the project is approved, Glencore expects it to have a mine life of more than 20 years and to initially produce 1.5 million to two million tonnes of coal a year, with production eventually growing to six million tonnes a year.

West Moberly First Nations and conservation groups have raised concerns about the mine’s potential impact on the Quintette caribou herd.

Tim Burkhart, the B.C. program manager with the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, said

“the region has seen a massive change to the land base due to industrial disturbance.”

“That’s pushed a lot of wide-ranging species and iconic species like caribou to the brink of extinction, and in some cases, has extirpated local populations of caribou,” he said.

The Sukunka mine would fall “smack dab” in the middle of the Quintette caribou herd’s habitat, a population that’s already impacted by existing coal mines in the region, Burkhart explained.

Alongside the threat to caribou, Burkhart said there’s a growing problem with selenium pollution in the Peace region and there are concerns about cumulative impacts from additional selenium contamination stemming from any potential new mines.

In a statement, Matthew White, the project leader for Glencore’s Sukunka project, said the project “remains on pause in the B.C. environmental assessment process. In the meantime, the working group continues to meet and Glencore is working to address questions and concerns raised at that table.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. Angello Johnson’s shoulders burn, and his arms...

Continue reading

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

We’re excited to share that an investigation by The Narwhal is a finalist for the...

A new documentary, Nechako: It Will Be a Big River Again, dives into how two...