Our trial is a week away

We’re suing the RCMP for arresting a journalist on assignment for The Narwhal. It’s an...

This is the third part of The Narwhal’s three-part series on the future of sustainable salmon.

Eric Hobson, a Calgary-based businessman with family roots in British Columbia, used to eagerly await Vancouver Island fishing trips with his father and brother. Salmon were plentiful, and he loved to catch coho and spring, grilling them fresh on the barbeque with a spatter of pepper and salt. But then gradually in the 1990s, everything changed.

“We used to fish for salmon in Cowichan Bay, off Vancouver Island, and then there were no salmon left in Cowichan Bay,” recalls Hobson, whose parents and grandparents were from Victoria. “And then we’d fish from an island on the inside around Parksville. And the fish started to disappear from there, so we moved to the west side. And the fish got less and less plentiful, and smaller and smaller.”

Once he had money and time, Hobson created the SOS Marine Conservation Foundation to try to figure out why wild salmon populations were in such steep decline. (The foundation later merged with the science-based charity Watershed Watch Salmon Society.)

“People that I fish with had told me that wherever the salmon farms go, the wild salmon perish,” says Hobson, who worked in the energy pipeline business as an electrical engineer, also co-founding an energy market trading company, a telecommunications company and a multi-media company.

He flew to Gilford Island in the Broughton Archipelago on B.C.’s central coast, the home of biologist and wild salmon advocate Alexandra Morton. It was there Morton offered to take him out in her boat to count sea lice on smolts around the salmon farms tucked into bays in the archipelago, a major migration route for juvenile salmon heading to sea.

“There were millions of smolts in these bays during the out-migration to the sea, and now we had trouble finding two dozen fish,” Hobson says in a telephone interview.

A juvenile wild salmon caught near B.C. salmon farms in the Broughton Archipelago. The young salmon is infested with sea lice which feast on the mucus, blood and skin of salmon and can cause death. Photo: David Mozkowitz

Biologist Alexandra Morton inspects a juvenile salmon for sea lice in her home on Gilford Island. Photo: David Moskowitz

Morton, a wild salmon advocate, gazes out the window of her home towards the Broughton Archipelago where numerous salmon farms are located. Photo: David Mozkowitz

“And the two dozen we found were covered with lice and were in various stages of dying. That really drove the problem home to me. When you have an open [net pen] system like that, it’s a breeding ground for parasites and pathogens. You have unprotected juveniles leaving the rivers, and the farms are located right on their migration paths.”

Hobson promptly formed another group — the SOS (Save our Salmon) Solutions Advisory Committee — to seek ways to mitigate any damage that fish farms were having on wild salmon populations.

“It became pretty obvious, pretty quickly, that the only way you could solve the problem once and for all was to put a solid wall up between the wild fish and the farmed fish. And so we started the whole process of developing the land-based closed-containment business in British Columbia.”

Kuterra, the first commercial sized land-based salmon farming facility in North America, was constructed one kilometre from the ocean in Port McNeill on northern Vancouver Island, after the SOS Marine Conservation Foundation signed a memorandum of understanding with the ‘Namgis First Nation. Designed and built by a Nanaimo company — and funded by the ‘Namgis First Nation, the federal and provincial governments and philanthropic individuals and organizations — the facility produced its first full-sized salmon for market consumption in April 2014.

Owned by the ‘Namgis First Nation, Kuterra harvested about 90,000 Atlantic salmon a year, which were sold in Safeway grocery stores and served for dinner in upscale restaurants such as Yew Seafood in Vancouver’s Four Seasons Hotel.

“If you balance swimming speed with the right feeding regime you get this well-exercised fish that is well muscled but still has a fairly high fat content,” Hobson says. “They’ve got a very, very nice mild taste and flaky texture. It’s absolutely delicious.”

Farmed Atlantic salmon swim in a closed-containment pond at the Kuterra fish farm. Photo: Kuterra

Hobson hoped the technology developed by Kuterra would spawn other land-based salmon farms in B.C. But more than six years later, only one other land-based salmon farming facility, West Creek Aquaculture in Agassiz, is operating, while land-based salmon farming operations pop up around the world in unlikely spots such as subtropical Florida, a Swiss mountain village and the desert near Dubai.

In 2019, the American aquaculture firm Emergent Holdings signed a 15-year lease on Kuterra, which has struggled to find sufficient capital.

Emergent Holdings said it would leverage Kuterra’s expertise to build one of the world’s largest land-based salmon farms in Bucksport, Maine — where other land-based salmon companies are also busy setting up shop. (Neither Kuterra nor Whole Oceans, the Emergent Holdings-owned company building the salmon farm in Maine, responded to requests for interviews.)

The story is similar on the east coast of Canada. Sustainable Blue produces land-based salmon in Nova Scotia’s Bay of Fundy and Cape D’Or Sustainable Seafoods, in Nova Scotia’s Advocate Harbour, uses salt water wells to imbue its land-raised fish with a flavour close to wild salmon.

Prince Edward Island is home to AquaBounty’s land-based Atlantic salmon facility, which is raising its first batch of genetically engineered salmon. The salmon have a growth hormone gene from chinook salmon — spliced into genetic coding from ocean pout, an eel-like fish — that allows them to grow to full size at twice the speed. They will be sold in Canada early in the new year, without labelling.

An AquaBounty genetically engineered Atlantic farmed salmon photographed in July 2020 on Prince Edward Island. Photo: AquaBounty

Many other locales now have a head start over B.C. when it comes to land-based salmon farming, according to a 2019 report from the Fraser Basin Council, which examined the economics of land-based salmon farming on Vancouver Island, finding it would create almost 4,000 direct and indirect jobs during the construction phase and 2,700 direct and indirect jobs during farming and processing operations.

“B.C. is not used to competing with Florida or Wyoming in the production of salmon,” the report said. “A new competitive reality must be recognized, and a crucial next step in attracting this industry is developing a cohesive plan for making B.C. competitive, and touting the advantage of locating here.”

But there is no cohesive plan for land-based salmon farming in B.C., the world’s fourth-largest producer of Atlantic salmon, as a decades-long dispute about open net pen salmon farms continues to simmer.

Wild salmon advocates, backed by scientific studies, say open net pen farms spread disease and sea lice to wild populations — already stressed by climate change and habitat loss — and point to mass escapes of Atlantic salmon in Pacific waters, where it’s feared they could compromise the genetic integrity of native salmon. They say the precautionary principle should be applied, which recognizes that conservation measures should be taken in the absence of scientific certainty when there is a risk of serious or irreversible harm to the environment using the best information available.

A salmon farm lights up the waters off the B.C. coast. Farms use artificial light to extend the feeding hours of the salmon. Photo: Tavish Campbell

The BC Salmon Farmers Association, representing some of the world’s largest salmon farming corporations, brandishes competing science reports, including from Fisheries and Oceans Canada, insisting that responsible open net pen salmon farming does no harm.

It doesn’t help matters, critics say, that Fisheries and Oceans Canada has a mandate to promote salmon farming as an industry and farmed salmon as a product — even though the Cohen Commission into the Decline of Fraser River Sockeye recommended the mandate be removed and the department “act in accordance with its paramount regulatory objective to conserve wild fish.”

And the federal government’s announcement on Dec. 17 that it will phase out 19 fish farms in the Discovery Islands, a key migration route for wild salmon, does not mean salmon farming companies will be switching to land-based production — even though more than 75 land-based salmon farming operations are planned, under construction or in operation around the world, including Atlantic Sapphire’s “Bluehouse” that raises Atlantic salmon on a former tomato field in Florida. By 2031, Atlantic Sapphire plans to raise 220,000 tonnes of salmon — more than double the amount produced each year in B.C. — in the Bluehouse, a name the company has trademarked.

“The science to produce large numbers of salmon on land just isn’t there yet,” John Paul Fraser, executive director of the BC Salmon Farmers Association, said in an emailed response to a request for an interview. “It is being developed, certainly, but no-one has yet successfully raised large numbers of fish on land without significant fish health or other issues.”

The association also throws cold water on land-based salmon farming in a November report that makes the case for open net pen farms, saying they can help lead provincial economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.

“There is no magical leap forward to having all production in closed containment or in large offshore technology in the near term,” the report says. “Salmon farming is part of the fabric of B.C., Vancouver Island and Indigenous coastal communities, and is committed to further growth through technology development and improvement, but not if the sole objective is to leave the water.”

Salmon smolts in a B.C. open net pen salmon farm. Photo: Tavish Campbell

The federal government’s position on a transition to land-based salmon farming is somewhat murky. In 2019, the federal Liberal party promised in its election platform to develop “a responsible plan to transition from open net pen salmon farming in coastal waters to closed-containment systems by 2025.”

But when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau issued mandate letters for his cabinet members several weeks later, he instructed his new fisheries minister, Bernadette Jordan, to work with the B.C. government and Indigenous communities “to create a responsible plan to transition from open net-pen salmon farming in coastal British Columbia waters by 2025.”

All mention of closed-containment systems had vanished, leaving the phrasing open to interpretation — an omission Stan Proboszcz, science and campaign advisor for the Watershed Watch Salmon Society, called “borderline deceitful.” Suddenly, it seemed the government only planned to make a plan by 2025.

In a telephone interview with The Narwhal, Terry Beech, parliamentary secretary to the Minister of Fisheries, Ocean and the Canadian Coast Guard, says the government can’t give an exact date or provide precise plans for taking open net pen salmon farms out of the water. But he says Ottawa is committed to a transition “and the transition is starting now.”

“We’re not waiting until 2025,” says Beech, the MP for Burnaby North-Seymour. “We’re looking at getting it started with a sense of urgency that reflects the concerns we’ve heard from various stakeholders in British Columbia.”

In January, Beech will lead formal consultations with First Nations and a group of representative stakeholders, including the salmon farming industry and environmental groups. By spring, he will deliver an interim report on transition plans to minister Jordan.

But Beech says a transition does not mean that B.C.’s open net pen salmon farming industry will move en masse to land, even though a 2019 report from Fisheries and Oceans Canada — released in February — concludes land-based salmon farming is ready for commercial development in B.C.

“I’m not going into this committed to a specific technology,” Beech says. “I’m going into this committed to moving the entire industry on the west coast to a more sustainable and predictable future, and I’m open to the technologies that could make that possible.”

One technology examined in the DFO report is known as the “super smolt” hybrid model. The model combines land and ocean-based systems, transferring salmon into open net pens later in their life cycle, where they grow to market size in nine to 12 months. But while the DFO report concluded the hybrid technology is also ready for commercial development in B.C., wild salmon advocates say it won’t address problems associated with open net pen farms.

A major problem is sea lice, a parasite that feeds on fish, causing stress and damage to their immune systems and making them more vulnerable to disease. Wild juvenile salmon are especially susceptible as they migrate past fish farms, where sea lice are sometimes so problematic that one company has used a barge to pressure wash the salmon.

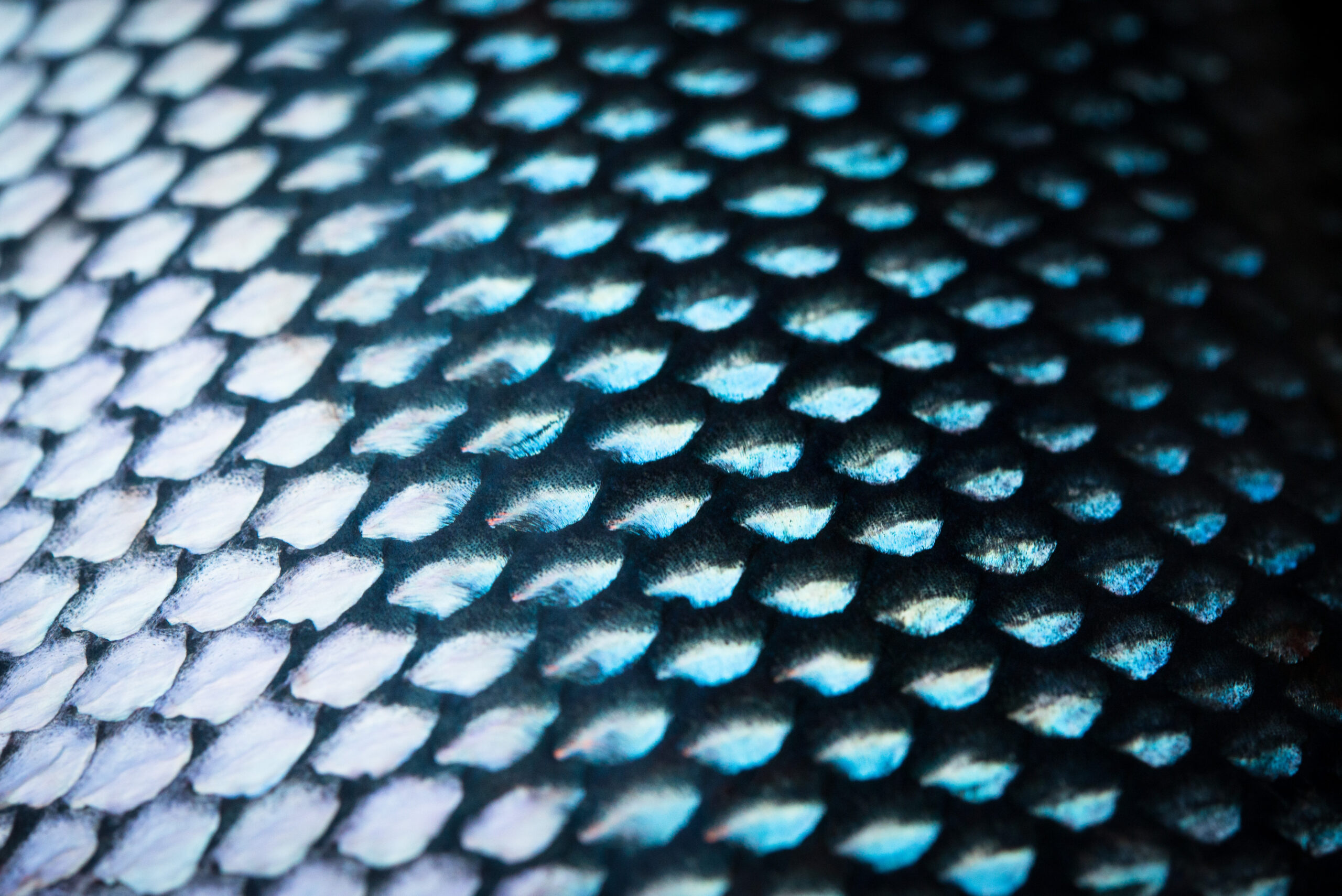

Healthy scales of a wild salmon. Photo: Tavish Campbell

A salmon infested with sea lice. Photo: Tavish Campbell

The hybrid technology would simply fill existing pens with larger fish, leading to increased waste discharge from the farms, according to Living Oceans Society executive director Karen Wristen. “It’s a scheme that benefits only the salmon farmers, because it allows the fish to achieve a greater size and a greater viability before they put them in the rather uncertain environment of the ocean,” she says.

And Wristen points out that investing in recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) to grow super-sized smolts is very different from building RAS facilities, like Atlantic Sapphire’s Bluehouse, to raise salmon from eggs to market size.

Building super smolt facilities could hinder development of a true land-based salmon farming industry in B.C., she says. “Those smolt farms will be located in places where they can readily serve the open net pens. That’s not necessarily where you would put your money in bricks and mortar if you were looking to develop a land-based industry.”

The DFO report also examined floating containment systems, where salmon live in an enclosed environment in the ocean, and offshore systems, which move salmon farms away from coastal areas and wild salmon migration routes. Floating containment systems need up to five more years to study, while offshore systems require 10 more years, the report concluded.

Wristen says open net pens would still be problematic offshore, and may not withstand the Pacific Ocean’s mighty storms. And it isn’t clear how the salmon farming industry would dispose of waste from floating closed containment systems, except to discharge it into the ocean, she says.

“I don’t see them being able to pipe the sewage to anywhere it could be treated, economically, so I’m thinking that one’s not coming to our coastline anytime soon. The cost of supplying diesel to a system like that is high, and environmentally destructive.”

In December, the salmon farming giant Cermaq announced a trial of a semi-closed containment system at its Millar Channel farm site, north of Tofino in Clayoquot Sound. The system uses a patented material to form a barrier around the net pen, eliminating “lateral interaction between wild and farmed salmon” and preventing the spread of sea lice, according to the company.

The technology shows promise in preventing sea lice infestations after it was piloted in Norway. But sea lice, which have become drug resistant, may adapt to go deeper in the water and circumvent the barrier, Wristen observes. “In the short-term it will alleviate the sea lice problem, but not the problem of pathogens and drugs being released into the marine environment.”

Beech says he is open to considering all technologies.

“I’m certainly not in the position to be closing the doors to any sort of technologies, either currently available, available in the near future, or available in the distant future, that can help us produce healthy, viable finfish aquaculture and food in a sustainable way, that allows us to grow a multibillion-dollar finfish aquaculture industry.”

In keeping with DFO’s other mandate, Beech also says it’s important to return wild salmon to traditional levels of abundance and restore “what is a very durable and culturally important multibillion-dollar wild salmon industry in British Columbia.”

Wild sockeye salmon. The year 2020 is set to record the lowest sockeye salmon returns on record. Photo: Tavish Campbell

Bob Chamberlin, a former fisherman and former vice-president of the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs, remembers when the Alert Bay harbour was so full of seine boats and gill netters that the bay seemed like a small city. He says only a handful of boats bob in the sheltered waters today. Each seine boat provided five jobs, and each gill netter supplied two jobs, notes Chamberlin, chair of the First Nations Wild Salmon Alliance and a member of the Kwikwasutinuxw Haxwa’mis First Nation.

“That’s what we could enjoy coast-wide when there were healthy and abundant wild salmon stocks. And there’s no way in the world that the fish farming industry can compete with that level of employment … If we were to work on salmon runs across this province, we would be able to reinvigorate a commercial fishery.”

While some First Nations, such as the Kitasoo/Xai’Xais First Nation on B.C.’s central coast, support open net pen salmon farming and the economic opportunities it brings to their remote communities, Chamberlin says the majority of First Nations in B.C. are opposed. The federal government’s decision to phase out Discovery Islands salmon farms was made after more than 100 B.C. First Nations, along with commercial and sport fishing groups and eco-tourism operators, demanded their removal, saying the farms posed a threat to endangered Fraser River wild salmon stocks.

Chamberlin’s own nation, along with two other nations in the Broughton Archipelago area, planned a celebration in the Alert Bay Bighouse in mid-March — it was cancelled due to the pandemic — to celebrate the planned closure of 17 open net pen farms in the archipelago over a four-year period, following intense negotiations with the B.C. government and the occupation of a salmon farm.

The Pacific Salmon Foundation has also endorsed a move to closed-containment salmon aquaculture, saying governments must put wild salmon first: “This transition to closed-containment will take time but the removal of open net-pen farms along migratory routes of wild Pacific salmon, particularly for those stocks of greatest concern, should occur as soon as possible,” the association said in a May 2018 position statement on aquaculture in B.C.

That’s in keeping with the 2018 recommendations of an advisory council on finfish aquaculture, which said the precautionary principle should be applied when assessing the threat of open net pens on wild salmon populations.

Chamberlin says unbridled transition to land-based salmon production would provide economic development opportunities for First Nations around the province.

“If we were to invest in wild salmon stocks and rehabilitate runs all over the province, it’s better for the environment,” he says. “It’s better for the economy. It can be put under the umbrella of a writ large reconciliation with First Nations across B.C. … It’s one of those things where everybody can win.”

The Fraser Basin Council report, co-authored by resource analyst Edwin Blewett, assumed the new industry would add to the current production of Atlantic salmon in open net-pens, and that a Vancouver Island-based industry would produce 50,000 tonnes of Atlantic salmon annually from individual farms operating at a 3,000-tonne scale.

A capital cost of $1.1 billion would be required to establish the industry, including $83 million for land, the report found.

But the salmon farming association warns the sole pursuit of land-based production would mean relocating investment and jobs to larger population centres or major markets outside B.C. “Even if it does become feasible, large land-based salmon farms would almost certainly not be built in our remote coastal communities, as they don’t have the land or access to water and power required and are not close to major markets,” Fraser said in the email.

Chamberlin says all industries must evolve, including the salmon farming industry.

“We don’t log like we used to,” he says. “We don’t mine like we used to. Certainly, oil and gas is changing as well. And this industry is still locked in the 1980s.”

“It’s time for evolution.”

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

We’re suing the RCMP for arresting a journalist on assignment for The Narwhal. It’s an...

As glaciers in Western Canada retreat at an alarming rate, guides on the frontlines are...

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...