Celebrating 7 years of The Narwhal — and gearing up for the next 7

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

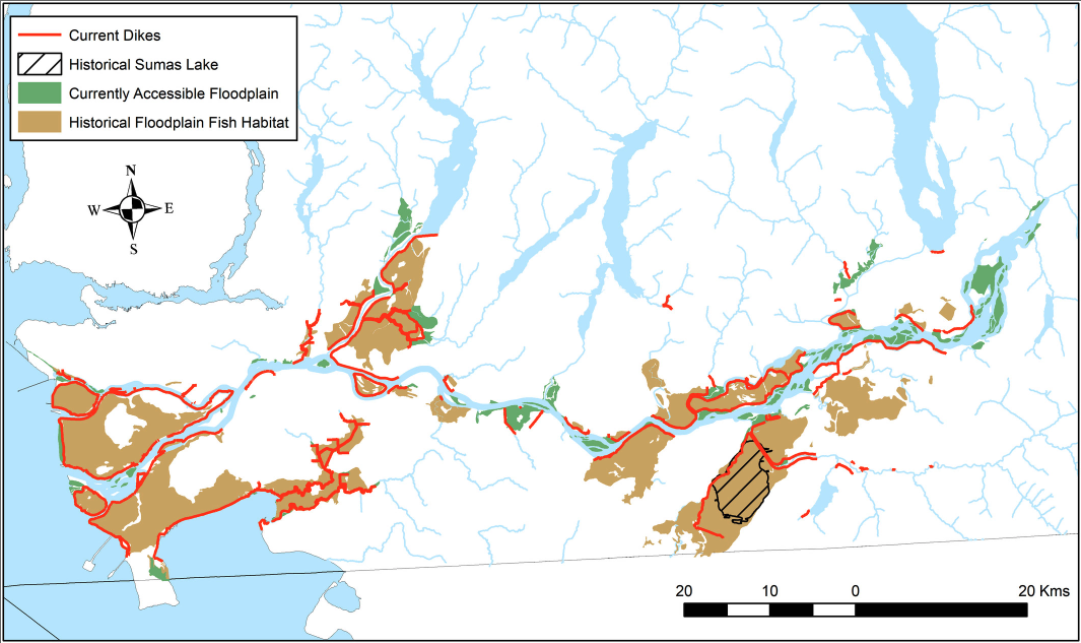

About 170 years ago, land surveyors walked through the floodplains of the lower Fraser River, making careful note of the types of vegetation they came across. The information contained in their 1859 to 1890 notebooks is part of what allowed researchers in 2021 to conduct a study that found up to 85 per cent of historical salmon habitat has been lost or obstructed by human-made structures.

According to lead author Riley Finn, a research associate with the Conservation Decisions Lab in the faculty of forestry at UBC, this study is the first to comprehensively quantify how much floodplain and upstream salmon habitat has been lost to structures like dams, flood gates and pump stations in the lower Fraser River — a key spawning and rearing habitat for Pacific salmon in B.C. that spans 20,203 square kilometres between Hope and Boundary Bay in South Delta.

“There always is this challenge in looking into history because we don’t explicitly have satellite imagery or the good data that we might have currently,” Finn told The Narwhal, explaining that access to vegetation records from the mid-1800s allowed him and his team to map where floodplain fish habitat used to be.

Complete and relevant datasets from historical surveys can be difficult to come by, Finn said, adding this kind of survey work can also tend to reflect the priorities of the people who were conducting them at the time. In this instance, the surveyors’ mission was part of a colonization expedition called the Dominion Land Survey, designed to identify how much agricultural land was available to be divided amongst settlers in the lower Fraser region.

That focused objective brought about a shortcoming in the historic data: the surveyors didn’t bother to study salt flats or any other places that wouldn’t have made for good farmland.

Still, the 170-year-old data provides a unique entry point to assessing the impact of habitat loss for salmon, a species that is struggling, particularly in the Fraser River.

Last year saw the lowest sockeye salmon returns in the Fraser River on record. Although runs are forecast to be higher this year — at 1.3 million fish versus around 280,000 in 2020 — numbers still aren’t high enough to support a fishery. Last summer, Fisheries and Oceans Canada launched an emergency plan to restore and recover habitat for Chinook and limit commercial fishing, noting that 12 of the 13 wild Fraser River Chinook populations, assessed by a committee that identifies endangered species, were found to be at risk.

Finn and his co-authors argue that while declining marine conditions due to climate change are an important factor in causing record low numbers of some salmon populations in the region in recent years, the magnitude of freshwater habitat loss is also playing a major role.

On top of the loss of the majority of floodplain habitat, the new study also found that in-stream flood protection barriers are cutting off migrating salmon in up to 64 per cent of the streams in the lower Fraser watershed.

Culverts — tunnels built under roads to channel streams from one side to the other — created to expand forestry activities on the lower mainland also often do not allow salmon to pass through, creating another type of barrier.

Over the years, these structures have served to disconnect historical salmon habitats, taking away precious spawning and rearing grounds and lowering the capacity of the region’s freshwater systems to produce wild salmon.

Researchers estimate that there are over 1,200 barriers blocking salmon access to about 2,224 kilometres of streams in the lower mainland. Of this, about 1,727 kilometres of in-stream habitat is believed to be lost after cities sprung up on top of them.

“When you’re in the lower Fraser, closer to the city of Vancouver and Burnaby, there’s habitat that’s just been completely lost,” said Dave Scott, the Raincoast Conservation Foundation’s Fraser Estuary Research and Restoration Coordinator, who is also a PhD student at UBC. “In Vancouver, there’s a number of streams that were completely paved over as urban development occurred.”

It is unrealistic to expect that historical salmon habitats will ever return to where they were in the 1850s given the large population of the Lower Mainland today, according to Scott.

“A lot of these barriers are related to flood control and the municipalities are not just going to remove these structures and allow their [communities] to flood,” Scott said.

The Fraser floodplain is home to over 300,000 people who are at risk of floods, and the Fraser Basin Council estimates a major flood could cost up to $30 billion in damages.

Scott also pointed out the need to work with agricultural land owners to come up with better ways to provide fish passage through their streams and waterways, while still maintaining the ability to farm.

Land conversion to agriculture is one of the ways in which freshwater stream systems have been disconnected and degraded in the area. Sumas Lake in the eastern portion of the Fraser Valley, for example, was drained in 1924 and is still kept dry with canals and pumps used for farming.

But, Scott said, finding a balance between human needs and salmon needs in the area could help restore Pacific salmon populations to sustainable levels. This balance can be struck by upgrading the existing infrastructure to create a way for salmon to pass through unharmed.

“A road culvert is really just supposed to pass water from one side of the road to the other, and maybe it does that now but it might not do it in a way that also allows salmon access,” Finn said. “It’s really about opening the conversation to having that infrastructure do more than just one thing, which is moving water, but also make sure that salmon capacity is [doing] well.”

With over 1,200 structures keeping salmon from their historical habitats, the next step is to find ways to prioritize which barriers to upgrade first — something Finn says his next paper, to be published at a later date, focuses on.

The process he has developed involves identifying areas that can be easily restored, figuring out how much habitat there is, and matching them with political will and funding opportunities.

Several organizations in B.C., like the Watershed Watch Salmon Society and Raincoast Conservation Foundation, are already working on figuring out which flood control structures should be upgraded first.

But even though the technology exists to build fish-friendly infrastructure, municipalities often continue to use outdated mechanisms that keep waterways off limits to salmon.

In February 2020, for example, residents of Pitt Meadows saw hundreds of dead fish at the McKechnie pump station — used to remove water from the stream and pump it into the main river to prevent flooding when water levels get high — when the animals got caught in the machinery and were killed.

Still, last year the city received one government grant and applied for another to replace two other pump stations with fish-friendly models. One of the major factors that keeps municipalities from switching to fish-friendly pumps is cost — machines that would allow salmon to pass through can be more expensive than existing designs.

A spokesperson from the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development previously told The Narwhal the province “encourages” fish-friendly infrastructure, but local authorities are responsible for developing that infrastructure.

For their part, the province and federal government have invested in a nearly $150-million salmon restoration and innovation fund to be distributed over five years to projects that protect and restore salmon populations.

One of the beneficiaries of this fund, MakeWay (formerly Tides Canada) received nearly $600,000 in 2019 to partner with Watershed Watch Salmon Society to identify flood control structures across the lower Fraser River watershed that need to be prioritized for infrastructure upgrades.

What these projects have not yet looked at are culverts in more rural or forested areas that also cut off in-stream access to migratory salmon.

“It’s kind of a mix of looking at the larger structures on the really large tributaries, and then the smaller structures that happen to isolate a lot of upstream habitat,” Scott said. “There’s definitely a lot of pieces to the puzzle to still figure out.”

For Finn, this paper provides important context for what has been lost by mapping out where salmon used to be able to spawn. Its findings should also be taken into consideration when coming up with current development projects, he says, so as not to continue limiting salmon access to the lower Fraser waterways.

Scott finds a silver lining in the study: “There’s a lot that we can actually do. I think our work shows the scale of habitat loss, but also shows the opportunity,” he said. “A lot of this habitat isn’t completely lost; it’s just behind a barrier.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits