A Kootenay conservation organization is urging the B.C. government to “stop stalling” and match a new, more stringent U.S. standard for selenium pollution in a cross-border lake downstream of Elk Valley coal mines.

B.C. and Montana spent years working to develop a new selenium limit for the watershed. Montana moved to implement the new standard last year and recently secured approval from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, as is required under the Clean Water Act.

North of the border, however, water quality objectives for selenium pollution remain unchanged.

“It’s time for B.C. to stop stalling on adopting a shared pollution limit,” said Lars Sander-Green, mining lead with the conservation organization Wildsight.

“The science is solid, it’s settled. Montana’s moved ahead, it’s time for B.C. to do the same,” he said.

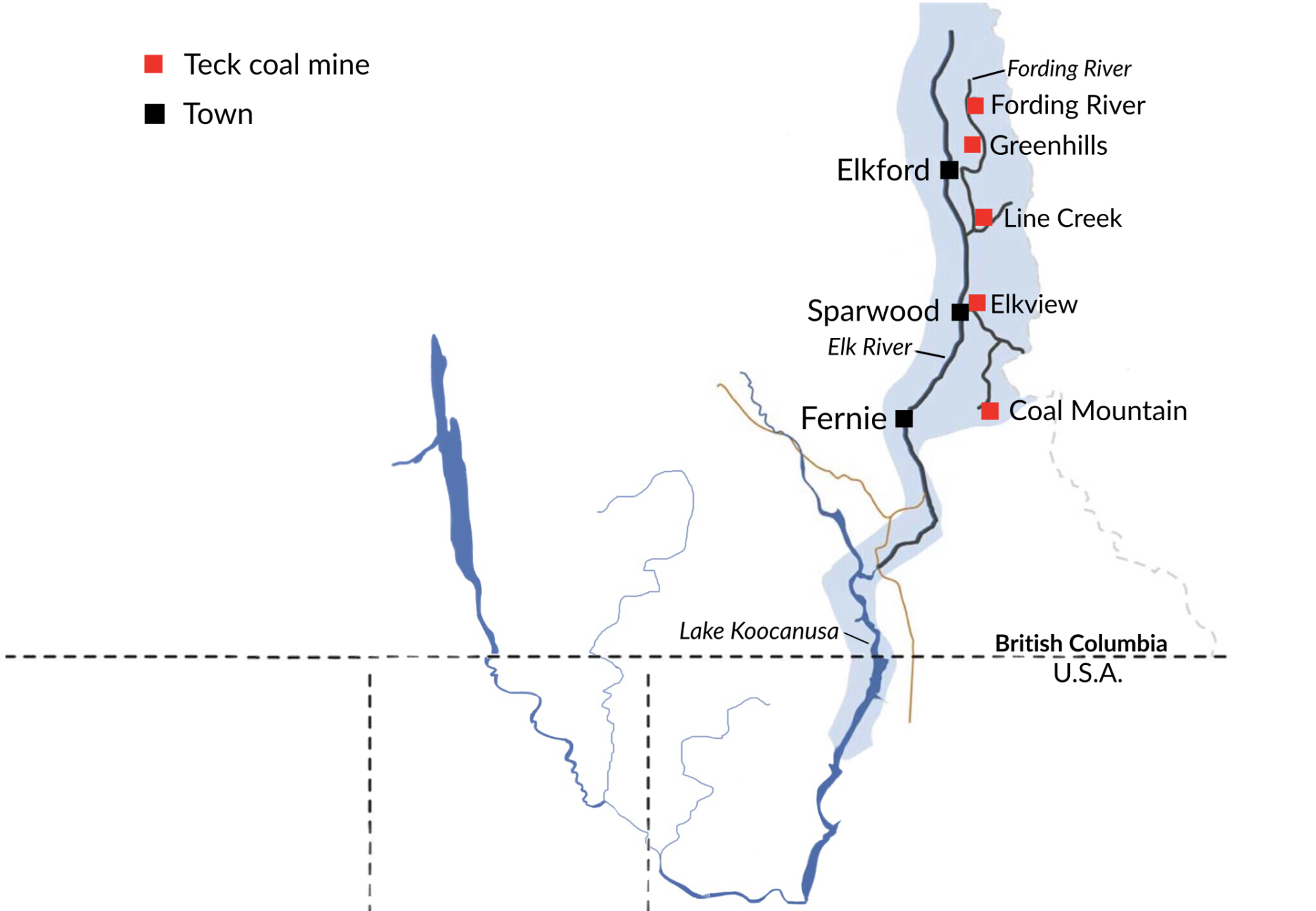

There are longstanding concerns in the Elk Valley about selenium pollution leaching from piles of waste rock at coal mines operated by Teck Resources.

While aquatic life, like people and other animals, needs some amount of selenium to survive, too much can have detrimental effects. When fish are exposed to elevated selenium levels, for instance, it can result in lower production of viable eggs, deformities, reduced growth, and even death, Myla Kelly, water quality standards manager with Montana’s Department of Environmental Quality explained to The Narwhal last fall.

Ninety-five per cent of the selenium entering Lake Koocanusa comes from the Elk River, which has been contaminated by current and historic coal mining in the Elk Valley, according to a September 2020 presentation by the Montana environment department.

Experts have long warned about negative impacts to fish from selenium in Elk Valley waterways where selenium levels as high as 150 parts per billion have been detected.

Last spring, Teck reported a dramatic decline in adult westslope cutthroat trout in Elk Valley waterways closest to its mines. Chris Stannell, a spokesperson for the company, said in a statement that the cause of the decline is still being investigated, but preliminary findings have been shared with government agencies and the Ktunaxa National Council and are under review. Stannell said those early findings suggest a combination of factors may have led to the decline but that water quality, including selenium, wasn’t a primary contributor.

Downstream, in Lake Koocanusa, average selenium levels are currently 1 part per billion, above Montana’s new standard of 0.8 parts per billion, according to the Montana Department of Environmental Quality presentation.

Meanwhile, B.C.’s general water quality guidelines, which apply to the Canadian side of Lake Koocanusa, recommend selenium levels be limited to 2 parts per billion — more than double Montana’s new standard.

Teck’s metallurgical coal mines are all upstream of the transboundary Koocanusa Reservoir. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

“We know that the current elevated level of selenium and other contaminants in the Koocanusa reservoir is a concern, and that is why we are working with everyone involved, including the Ktunaxa Nation Council to ensure the best available science is employed so that fish and aquatic health is protected,” David Karn, a spokesperson for B.C.’s Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy, said a statement.

Once a water quality objective is approved, it would be considered in permitting decisions and as part of any required enforcement actions, the statement explained. However, meeting that objective would not be a legal requirement in B.C.

Coal mining operations are ongoing at four active Teck Resources operations in B.C.’s Elk Valley. Photo: Callum Gunn

With new coal mines proposed for the Elk Valley, Sander-Green wants to see B.C. adopt a more stringent objective for selenium to ensure that the new limit is considered as part of the environmental assessment processes.

Teck’s proposed Castle Mountain coal mine, now called the Fording River Extension Project, is also facing a federal assessment, which Sander-Green said will have to consider the transboundary concerns about selenium.

In a statement, Stannell said Teck “is committed to protecting water quality on both sides of the border, including Lake Koocanusa and we have made significant progress to date implementing the Elk Valley Water Quality Plan.”

The company has invested in treatment facilities to remove selenium and expects to increase water treatment capacity to 47.5 million litres of water per day later this year, the statement said. By 2031, the company is planning to be able to treat 120 million litres of water per day.

Sander-Green — who noted it’s not clear how much water is currently treated relative to the amount of pollution flowing from mine waste rock — is concerned that water treatment facilities are not a sustainable long-term solution to a problem that could persist long after the mines have shut down.

He wants to see the issue referred to the International Joint Commission, a Canada-U.S. body guided by the 1909 Boundary Waters Treaty that can investigate and makes recommendations to resolve transboundary water disputes.

Read more: The watershed watchers: in conversation with the International Joint Commission

“We know that no matter what the limit is, no matter what happens with future mines, you’ve got a long-term water problem across the border,” Sander-Green said.

“This is the kind of thing that one might think would go to the International Joint Commission,” said Richard Paisley, a lawyer and director of the Global Transboundary International Waters Governance Initiative at the University of British Columbia. And, while the commission cannot enforce orders, Paisley said it has significant moral and political authority.

The challenge is that “as a matter of practice, the International Joint Commission only accepts matters which are jointly referred by both countries,” he said.

“In this case, for example, the U.S. would have at first blush a legitimate concern,” he said.

Before agreeing to a joint referral, the Canadian government would likely consult the B.C. government, which may be reluctant to send the matter to the commission, Paisley said.

“And, Canada has generally given great deference to the provinces.”

Sarah Lobrichon, a public affairs advisor for the joint commission, said in a statement that the commission has discussed the issue with both the U.S. and Canadian governments and “stands at the ready to assist the Governments of the United States and of Canada should a reference be provided.”

In a statement, a spokesperson for Global Affairs Canada said: “The Government of Canada takes the environmental impacts of mining seriously and we are working hard with our provincial and transboundary partners to ensure that appropriate actions are taken to protect the environment.”

At the same time, Environment and Climate Change Canada is working to develop new regulations under the Fisheries Act for coal mining effluent in an effort to reduce the risk of contaminants such as selenium, spokesperson Samantha Bayard said in a statement.

Sander-Green said a decision on whether to refer the issue to the joint commission “really comes down to the pull that B.C. has in Ottawa versus the pressure from the American side or the desire to clean up this issue in the long-term.”

“It’s pretty clear that B.C. doesn’t want to see this go to the [International Joint Commission] because it’s going to look bad for B.C.”