‘Afraid of the water’? Life in a city that dumps billions of litres of raw sewage into lakes and rivers

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Internal documents show the B.C. government and mining giant Teck Resources quietly lobbied senior federal officials to quash a potential Canada-U.S. inquiry into transboundary water pollution from Teck’s coal mines in southeast B.C.

A February 2022 document prepared for senior provincial officials states “B.C. remains opposed” to the possibility of an inquiry into the extensive contamination.

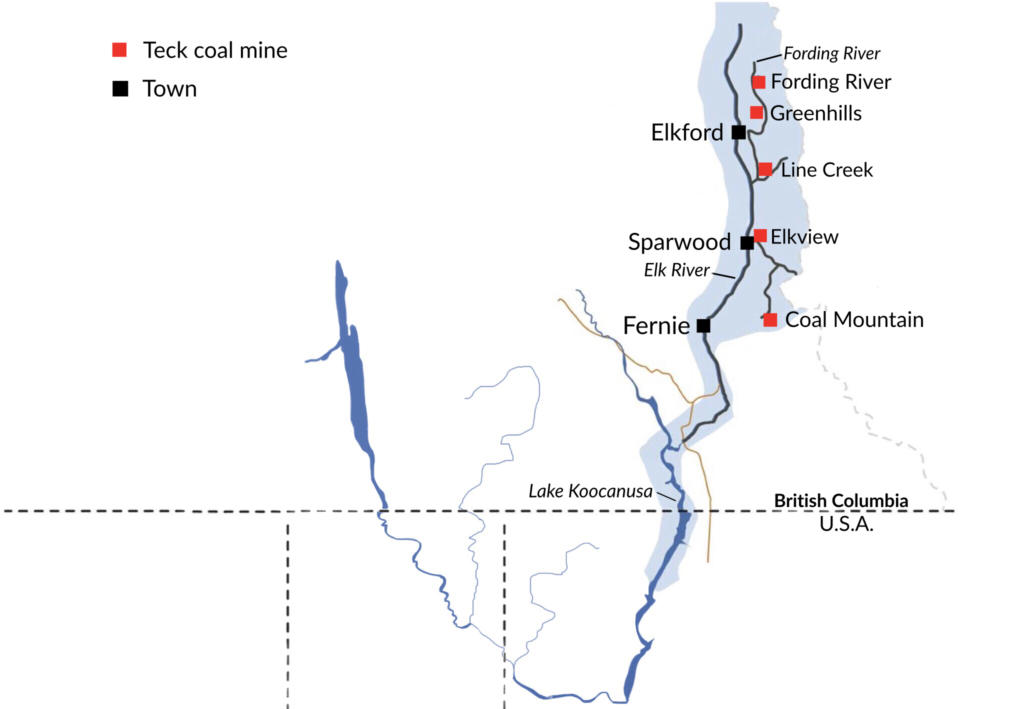

Teck operates four active mines in the Elk Valley, which produce metallurgical coal used in the steel-making process. The mines are upstream of the Fording and Elk Rivers, whose waters ultimately flow into the United States. For decades, selenium, an element that can cause deformities and impede reproduction in fish and other wildlife, has leached from the enormous piles of waste rock left over after the coal has been stripped and shipped away. Government inspection records from last year show selenium concentrations more than 100 times higher than levels considered safe for aquatic life have been detected in the Fording River, downstream of two of Teck’s mines.

That water then flows into the Elk River, before merging with the Kootenay River at Lake Koocanusa, a transboundary reservoir created by Montana’s Libby Dam. From there, the water travels along the Kootenai River through Montana and Idaho before flowing back into B.C.

“The fact that we’re getting pushback from B.C., it’s just unimaginable,” Yaq̓it ʔa·knuqⱡi ‘it Nasuʔkin (Chief) Heidi Gravelle said in an interview.

Yaq̓it ʔa·knuqⱡi ‘it, also known as the Tobacco Plains Indian Band, is one of several communities that make up the Ktunaxa Nation, whose territory covers parts of the region known today as B.C., Alberta, Montana, Idaho and Washington State. Over the last decade, the Ktunaxa Nation Council, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho, which are all part of the transboundary Ktunaxa Nation, have repeatedly called on the Canadian and U.S. governments to refer the persistent pollution from Teck’s mines to the International Joint Commission — an organization established to prevent and resolve disputes relating to shared waterways between the two countries.

“You think you’re making headway when it comes to doing the right thing and putting our environment and ecosystem first,” Gravelle said. To then learn that’s not the case is both “disheartening” and “frustrating,” she added. “My kids, my grandkids will never get the experience from the Elk River that I did, or my dad did or that my grandparents did.”

“When those areas are disturbed — and more than disturbed, completely and entirely annihilated through contamination — our livelihood is taken away,” Gravelle said. “Who we are is ripped from us.”

The internal documents, obtained by the Ktunaxa Nation Council through a freedom of information request to the B.C. government, show the province actively pushed its federal counterparts to reject calls for the commission’s involvement.

The internal emails and letters between the provincial government, Teck and the federal department of Global Affairs Canada “substantiate what we have long suspected,” Calvin Sandborn, senior counsel at the University of Victoria’s Environmental Law Centre, told The Narwhal. “The government of British Columbia is aligning itself with Teck Corporation and acceding to the request of Teck to oppose an International Joint Commission reference.”

The commission was created under the 1909 Boundary Waters Treaty to study and recommend solutions to intractable disputes. Conservation groups on both sides of the border and the U.S. Department of State support the commission’s involvement in this case.

The commission launches a study of transboundary issues at the request of national governments. These requests are called references. Once a reference is received, the commission appoints a professional board of experts from each country to review the issues.

Global Affairs Canada and the U.S. Department of State had been in talks over a possible reference to the International Joint Commission. But in late April, a federal official emailed the Ktunaxa Nation Council to say the Canadian government had “decided [International Joint Commission] involvement was not the best route at this time.”

The newly released B.C. internal documents show B.C. Environment and Climate Change Strategy Minister George Heyman and Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources Minister Bruce Ralston wrote in an April 2022 letter to Foreign Affairs Minister Mélanie Joly that “the province maintains there are other, more efficient ways to address concerns around selenium levels.”

In an interview with The Narwhal last November, Heyman would not comment on whether the province supported referring the contamination issue to the joint commission. But these newly released documents reveal his government had already taken a position.

Months earlier, B.C.’s deputy minister of Intergovernmental Relations Secretariat wrote in a August 2021 letter to the deputy minister of Foreign Affairs in Ottawa: “It is the view of the Government of British Columbia that pursuing a referral to the [International Joint Commission] would compromise ongoing cross-border environmental management efforts which are on track to address concerns that have been raised.”

In their April 2022 letter, the B.C. ministers went on to say it was “more important than ever” to support the province’s metallurgical coal mining industry to meet growing global demand for steel, which among other things is a feedstock for the low-carbon economic transition. The ministers also pointed to the several thousand people employed by the mines and significant government revenue generated each year by the company’s coal operations.

“It’s disturbing” and “disheartening” the B.C. minister of environment would oppose a reference to the International Joint Commission, Sandborn, legal director of the Environmental Law Centre, said, adding the commission is an objective group that has found innovative, win-win approaches to pollution problems across the US-Canada border for over a century. “They’re experts seeking a solution. How can that be threatening?”

A spokesperson for B.C.’s Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy did not directly respond to questions asking why the provincial government opposed involving the joint commission.

Despite B.C.’s concerns, and comments to Ktunaxa Nation by one of its own officials, the federal government is still considering a possible reference to the International Joint Commission, Kaitlin Power, a spokesperson for Environment and Climate Change Canada Minister Stephen Guilbeault said in an emailed statement to The Narwhal.

In the meantime, provincial staff are prioritizing work to address water quality issues in the Elk Valley, a spokesperson for the B.C. Environment Ministry said.

“We will continue to work with Nations, U.S. and Canadian federal agencies, and the State of Montana to understand where there might be gaps in existing processes and to find the best place to address them,” the statement said.

Discussions between the province and the federal government excluded the Ktunaxa Nation, Chief Gravelle said — a move she called “frustrating” and “belittling.” In a press release, Ktunaxa Nation Council said the documents show provincial and federal governments have failed to uphold their legal obligations to Ktunaxa Nation and their commitments to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

“The released documents reveal that officials from the highest levels of the federal and provincial governments engaged in discussions about the reference which excluded Ktunaxa and ignored Ktunaxa title, rights and governance authority,” it said.

In a statement, the spokesperson for B.C.’s Environment Ministry said the province “continues to be engaged with all parties to improve water quality in the Elk River Valley without the involvement of the International Joint Commission.”

“We have been consistent on this position and have been engaged with all levels of government, including the Government of Canada, on ongoing plans for the region,” the statement said.

The records released in the freedom of information request show a senior Teck executive also lobbied the federal government to abandon any potential reference to the commission.

Teck — which reported a gross profit of $1.2 billion from its steel-making coal operations in the third quarter of this year — operates the four active metallurgical coal mines in the Elk Valley. The company also has a proposed mine undergoing environmental assessment.

In a letter to Global Affairs Canada this past spring, Teck’s then senior vice president of sustainability and external affairs Marcia Smith said involving the joint commission would be the “wrong approach.”

She said a reference to the commission would not only impact Teck but also “negatively impact the reputation of Canada’s regulatory system.”

Speaking to The Narwhal earlier this month, Gravelle dismissed the concern. “The harm has already been done, the reputation’s already been completely damaged.”

Smith’s letter went on to raise concerns that International Joint Commission involvement “could delay permitting and projects vital to Canada’s ability to continue to produce much needed steel-making coal.”

She also wrote it would “distract” from the company’s ongoing efforts to address the selenium contamination. “At worst, it could be a de facto derailment,” she said.

In a statement to The Narwhal, Teck’s public relations manager Chris Stannell reiterated the company’s position, writing “there are other more effective ways to address selenium concerns in the Koocanusa Reservoir underway that involve transboundary collaboration.”

Efforts have been made to address the selenium levels in the Elk Valley. At the request of the B.C. government in 2013, Teck developed the Elk Valley Water Quality Plan with input from affected First Nations as well as B.C. and U.S. government agencies, to address contamination from coal mining in the watershed.

Stannell said Teck Resources has so far invested $1.2 billion in water treatment and other measures and plans to invest an additional $750 million over the next few years. In an email to The Narwhal, Stannell said the company works “with stakeholders on both sides of the border to make water quality data publicly available.”

The company’s existing water treatment plants “are effectively removing 95 per cent of selenium from water,” Stannell said. He added that selenium concentrations “have been stable for at least a decade and are lower than in many other water bodies in the state of Montana.”

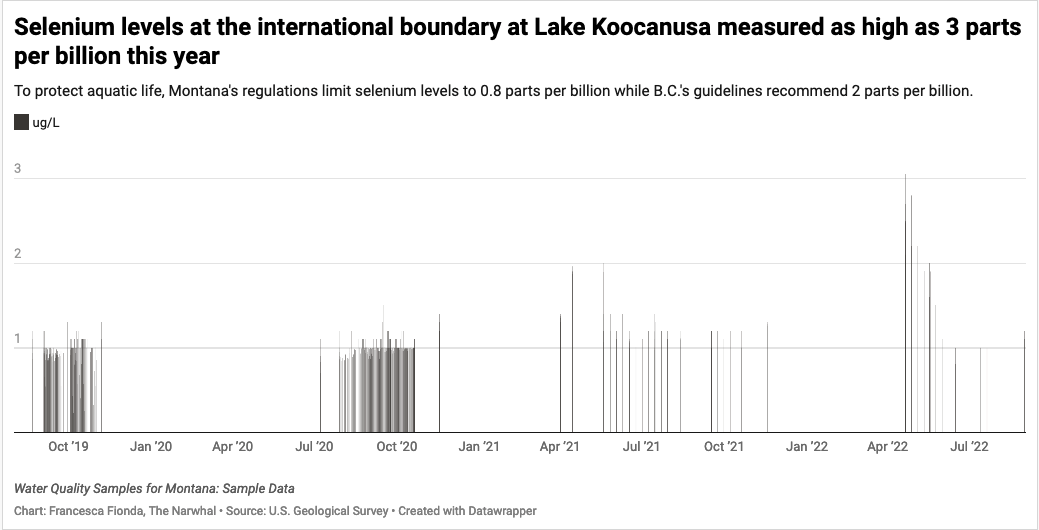

But Environment and Climate Change Canada data shows selenium inputs to the Koocanusa Reservoir from the Elk River are rising. Levels in both the Koocanusa and the Kootenai River downstream have been increasing for years, according to Erin Sexton, a research scientist at the University of Montana’s Flathead Lake Biological Station who has worked with the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes.

“B.C.’s regulatory process has failed to do anything about those increasing contaminant trends, Teck Coal is years behind in terms of implementing mitigation for those contaminants,” she said.

So far, Teck’s efforts haven’t proven to be effective according to Wyatt Petryshen, mining policy and impacts researcher with the environmental group Wildsight. “Selenium concentrations have continued to rise despite those best efforts,” he said.

The province has also failed to address concerns around selenium, Sandborn said. While Teck was recently ordered to pay $60 million for polluting waterways in the Elk Valley, there are dozens of instances where Teck was not penalized for toxicity contraventions over the years.

“The regulatory negligence that the province of British Columbia has shown in regard to this coal pollution has been wretched,” Sandborn said.

Sandborn and his students at University of Victoria’s Environmental Law Centre prepared a 2021 submission for Wildsight on the pollution in Elk Valley. It described the mine discharge in the area as “one of the world’s largest selenium contamination events — and one of North America’s most serious pollution problems.”

South of the border, U.S. state, federal and Tribal agencies are investigating the spread of the contamination.

Travis Schmidt, a United States Geological Survey research ecologist leading the agency’s Lake Koocanusa monitoring program, said in an email to The Narwhal that in each of the last few years higher selenium concentrations have been detected at the international boundary in the reservoir than previously recorded. The agency is building a year-round monitoring program to better understand how selenium concentrations are shifting over time at the international boundary and what factors are contributing to those changes.

A watershed board within the International Joint Commission would bring together all the groups impacted by mining in the Elk Valley within an impartial and transparent framework to make decisions, Petryshen said. Without it, “it’s mostly Teck and the province making decisions for everyone else,” he added.

The commission would also provide independent experts who could set objective standards and make pollution data accessible, Sandborn said. “Under the current system in British Columbia, scientists can’t get the data they need to analyze and fix the problem.”

One of the challenges, Sexton, the scientist at the University of Montana, said, is B.C.’s professional reliance system under which Teck is responsible for collecting its own data and monitoring itself.

Teck is selective about the data it releases publicly, Sexton said. “If I want to know what is the volume of contaminated water coming down from the mines in the Elk Valley and how much of that is being treated — I can’t find that information anywhere. It doesn’t exist on any public website or any publicly available document,” she said.

According to Teck, the company has the capacity to treat more than 47 million litres of water every day. What’s not clear is what proportion of contaminated water is being treated. The Narwhal has repeatedly asked the company for that information, but Teck has so far not provided it.

Petryshen, who has been investigating the impacts of coal mine expansion in the Elk Valley for Wildsight, believes the volume of water being treated by Teck’s facilities is too low to be effective. Unless Teck can drastically ramp up their water treatment Teck should pause on any expansions, Petryshen said.

In a statement to The Narwhal, the B.C. Environment Ministry said “in response to data accessibility concerns we have heard, B.C. is developing and intends to launch a new online tool to improve availability and transparency of information and data related to water quality and regulatory activities in the Elk Valley.”

The province is also working with the four Ktunaxa First Nations on a proposal to update the Elk Valley water quality plan, the statement said.

In the meantime, Richard Janssen, the natural resources department head for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, said the data shows selenium is trending up.

“If you continue at this rate, it’s going to have even drastic or more detrimental effects to our cultural resources, the land that we enjoy, the flora and fauna, the birds — the fish is a big one that we have subsistence rights,” he said.

“We are firm on our stance that an [International Joint Commission] is the way to go, where it’s transparent, it brings all stakeholders at the table to come up with a solution that will benefit all to keep these natural resources healthy and pristine for the next generations,” Janssen said.

There is a possibility that a reference to the International Joint Commission could go ahead whether or not Canada agrees. A reference to the committee, without the support of both countries, has never been done in the more than 100-year history of the organization, according to an email between federal and provincial officials, obtained through a freedom of information request by Ktunaxa Nation Council. In a letter from Teck to Canada’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mélanie Joly, a Teck senior executive warned a unilateral reference “would stand as a flagrant jurisdictional overreach.”

The commission has stated it is prepared to move forward and act on a request from the U.S. without Canada. B.C.’s Minister of Environment and Minister of Mining are “standing in the way,” Sandborn said. “It’s a serious international issue. Is Canada going to be a co-operative problem solver on pollution or not?”

Meanwhile, Minister Guilbeault is preparing to welcome the world to Montreal for the United Nations biodiversity conference this December.

“Nature knows no boundaries — not local, not provincial or territorial and not international. We are all in this together,” Guilbeault recently wrote in an op-ed published by The Narwhal. Thousands of international delegates will be attending the 15th annual Convention of Parties (COP15) to discuss the world’s declining biodiversity.

Canada has international legal obligations under the Boundary Waters Treaty and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Petryshen at Wildsight said the federal government is between a rock and a hard place given B.C.’s stance on the issue.

Ultimately, Petryshen believes the best mechanism to address these trans-boundary pollution concerns is through a joint reference with the U.S. to the International Joint Commission. “The [International Joint Commission] is the most transparent and impartial framework in which we can solve this problem.”

Gravelle agrees. “What happened in the valley has been an extreme example of when you do things wrong, for the sake of every dime on the table you get detrimental impacts that are completely irreversible, that are now trickling down the water streams and affecting the livelihood and the inherent right of the original people, which is wrong,” she said.

“At the end of the day, what do we do? We won’t give up, we won’t stop, because enough is enough.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

Break out the champagne: Emma’s storied life and leadership in journalism has earned her the...