Rocky Mountain coal mine in Alberta takes next step to expansion

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

As Teck Resources plans to distance itself from coal, government records show the mining giant remains a long way from solving the widespread contamination of local rivers and creeks — despite having already invested $1.2 billion in water treatment.

Last year, selenium levels 267 times higher than what’s considered safe for aquatic life were detected in waters directly affected by Teck’s Elk Valley mines, according to an internal government meeting note obtained by The Narwhal through a freedom of information request.

Teck removes some contaminants through water treatment, but the vast majority of both selenium and nitrate pollution still flows downstream without any treatment at all, according to information on a new government website, called the Elk Valley Water Quality Hub.

“The levels of selenium that you see throughout the Elk and Fording Rivers are alarming, and they have been alarming for a long time,” Erin Sexton, a senior research scientist with the University of Montana’s Flathead Lake biological research station, said in an interview.

Selenium, a naturally occurring element, is dangerous when present in water where it is consumed by zooplankton and other invertebrates, which are in turn eaten by fish and birds. In fish, even small concentrations of selenium can cause severe birth defects, reproductive failure and population crashes.

“It begs the question, what are the long-term population trends for native trout, for bull trout, for westlope cutthroat trout in the Fording and Elk Rivers?” she said. “And, at what point do these levels of contaminants become a breaking point?”

Now, as Teck moves to separate its coal and copper businesses, there are growing concerns about the company’s ability to stem the flow of contaminants, particularly in light of plans for new mining in the region. The company is asking shareholders to support spinning off its coal mines as a separate entity called Elk Valley Resources, which now counts former premier John Horgan among its board members.

The deal would see Teck take 90 per cent of Elk Valley Resources’ free cash flow for about 11 years. To Wyatt Petryshen, mining policy and impacts researcher with the conservation organization Wildsight, the structure suggests Teck wants the benefits of the coal mines, without the responsibility for environmental liabilities down the line.

In a previous statement to The Narwhal, Chris Stannell, Teck’s public relations manager, said the separation “will have absolutely no effect on meeting environmental obligations in the Elk Valley.” Teck currently manages its coal mines under the Elk Valley Water Quality Plan, a document put in place in 2014 that outlines the company’s aims to reduce the amount of selenium and other pollutants in the watershed over time.

The new company, Elk Valley Resources, “will be fully committed to the ongoing implementation of the Elk Valley Water Quality Plan,” he said.

Petryshen warned the province and taxpayers should be wary. If the deal goes through, “the province needs to make sure that the coal mines are fully bonded,” he said. And an independent audit should be done to ensure there’s enough money to cover long-term water treatment and remediation, he said.

Currently the environmental liability for Teck’s Elk Valley mines is estimated to be $1.71 billion. According to the 2021/2022 annual report from the Chief Inspector of Mines the company still owes $431 million in reclamation security.

Teck’s coal mines release a number of damaging contaminants into nearby waterways, including calcite, which solidifies the loose gravels fish rely on to create protective nests for their eggs. But selenium has long been a central concern.

In 2021, Elk Valley coal mines were the highest contributors of selenium pollution to waterways in Canada, according to a Ktunaxa Nation Council submission to the B.C. Environmental Assessment Office last summer, which cites data from the National Pollutant Release Inventory.

To mine coal, Teck systematically strips away mountain tops, creating open-pit mines. The process leaves massive piles of leftover rock behind. As those piles are exposed to rain and snowmelt, selenium leaches from the waste rock and finds its way into local creeks, rivers and groundwater.

“Look hundreds of kilometres down river from the mines, into the Kootenai River of Idaho, and you can see selenium is increasing in fish tissue,” Sexton said. “The only source of that selenium is from the five open-pit coal mines that are leaching in the Elk Valley.”

When fish transfer the contaminant through their eggs, their larvae may be born with curved spines, misshapen skulls, abnormal gills or fail to hatch at all — effects that have already been observed in waters polluted by Teck’s mines.

“Aquatic ecosystems in most of the mainstems are functioning, but chronic toxicity impacts are present at some locations in the Elk Valley,” an internal government meeting note from March 2022 says.

To protect aquatic life from harm the B.C. government says selenium concentrations should be kept to two parts per billion.

But Teck isn’t required to meet that standard in most of the waterways it pollutes. The company’s permit allows selenium levels to reach 63 parts per billion, for instance, in the Fording River downstream of its mines. That’s 31.5 times higher than what B.C. considers safe for aquatic life and a limit Teck exceeded in January, February, March and April last year.

Selenium levels are higher still in the creeks Teck draws water from for treatment. According to the internal government meeting note, selenium levels varied between 171 parts per billion to 534 parts per billion before treatment at one of the company’s three facilities. After treatment, selenium levels were reduced to between 8.48 parts per billion and 24.6 parts per billion.

“It boggles the mind that there’s even a proposed mine expansion on the table, they’re that far out of compliance,” Sexton said. “Their wastewater treatment facilities are not performing as expected, they’re years behind in implementing them.”

The pollution has taken a considerable toll on Ktunaxa Nation.

While people still fish the rivers for pleasure, “nobody will eat fish out of there because of the contaminants, which is sad,” Yaq̓it ʔa·knuqⱡi ‘it Nasuʔkin (Chief) Heidi Gravelle previously told The Narwhal.

A draft human health risk assessment concluded that eating fish from contaminated waters at preferred rates of consumption put Ktunaxa “at increased risk in the Elk Valley due to selenium exposure,” Ktunaxa Nation Council wrote in its submission to the Environmental Assessment Office last summer on the readiness of Teck’s proposal for a new mine in the region.

According to Stannell the draft human health risk assessment is under review by the environmental monitoring committee and is expected to be posted publicly in the coming months once the review is complete.

A 2020 report for the International Joint Commission found “people relying on subsistence fish (and aquatic plant) harvests may have substantially higher selenium exposure than recreational fishers.”

Too much selenium over the long term can lead to selenosis, symptoms of which can include diarrhea, nausea, fatigue as well damage to hair and nails.

Stannell, Teck’s public relations manager, said water quality downstream of its mines meets the standards set out in the company’s permit 95 per cent of the time.

Concentrations of contaminants “are influenced by seasonal variation in flow as a result of snowpack melt and precipitation,” he said.

The Elk Valley Water Quality Plan aimed to stabilize selenium levels by 2023 and reduce the pollution by 2030.

Stannell said the plan “is improving water quality.” But Teck’s 2022 implementation plan shows the company could exceed current selenium limits in some areas as late as 2027. And even if the company is able to bring pollution levels in line with its permit, selenium concentrations would still be well beyond what’s considered safe for aquatic life.

While Teck’s treatment facilities are reportedly removing selenium from treated water, their overall effectiveness ultimately depends on what proportion of total contaminated water is being treated. Reports show this proportion is relatively small.

The company is eager to point out it has the capacity to treat 77.5 million litres of contaminated water a day at its treatment facilities and that it’s removing 95 per cent of the selenium from that water. More water treatment facilities are in the works with a goal to increase capacity to 142 million litres per day by 2027.

But the majority of selenium contamination still flows downstream untreated.

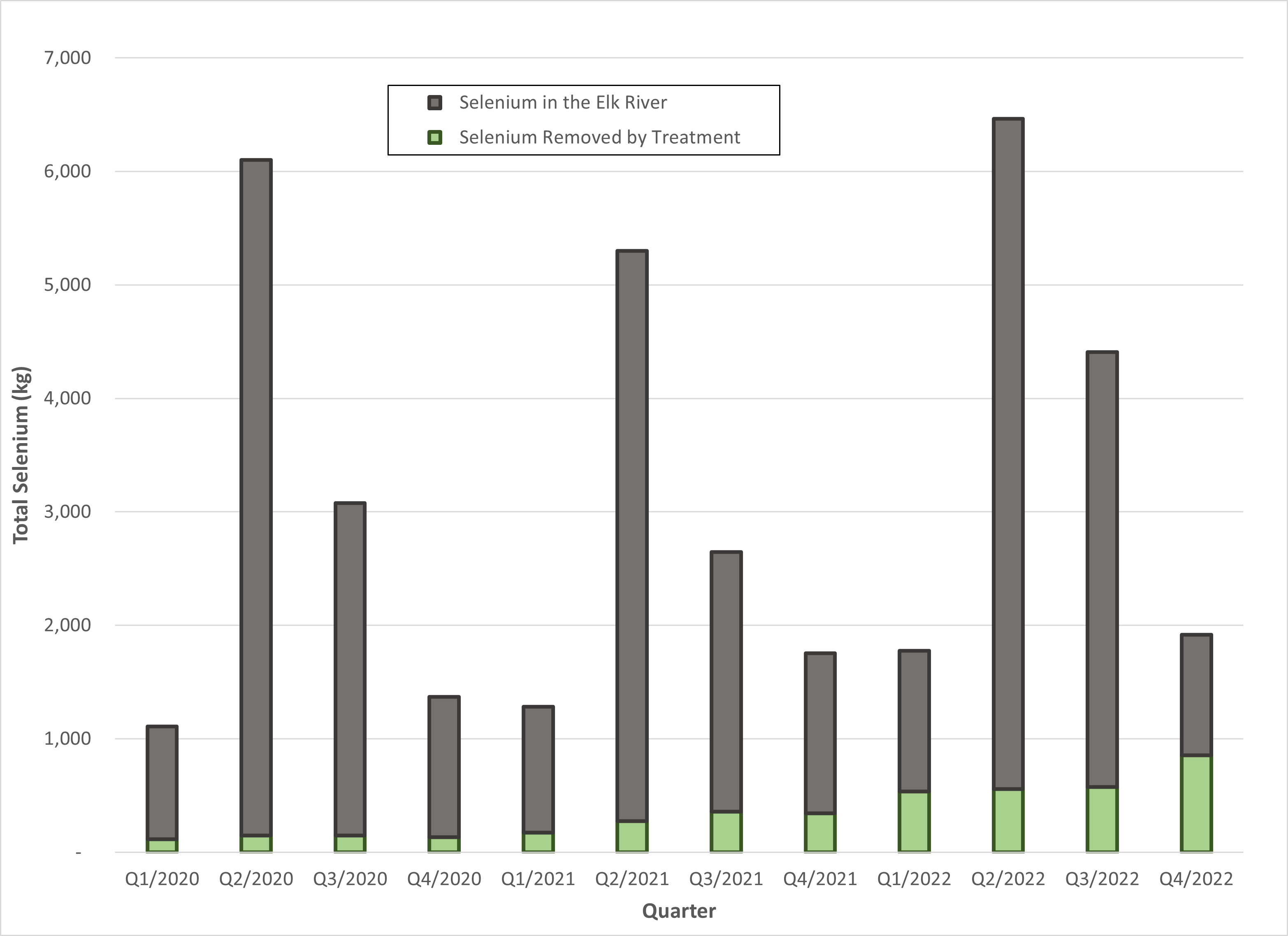

Teck’s water treatment facilities have removed about 500 to 1,000 kilograms of selenium each year since 2016, Ktunaxa Nation Council notes in a submission to the Environmental Assessment Office last summer. That’s five to 10 per cent of the 10,000 kilograms of selenium the mines release into local waterways each year, the documents note.

“Teck has yet to demonstrate the successful removal of selenium loadings that are released each year,” Ktunaxa Nation Council wrote.

A graph posted to the government’s new Elk Valley Water Quality Hub also shows Teck is removing only a portion of the selenium that pollutes the Elk River.

“They must be missing a ton of water if you’re still having loads that large,” Petryshen said during a video interview as he looked over at the graph. “That really paints a picture that the water treatment’s not really doing that much.”

The company’s water treatment facilities have also been plagued by delays — the reason for a recent $15,480,000 fine under B.C.’s Environmental Management Act — and unexpected water quality issues.

During start-up Teck’s West Line Creek treatment facility, for instance, inadvertently caused a fish kill event for which the company was ordered to pay $1.4 million in fines. The company has stated that the incident was related to the unintentional release of high levels of ammonia, nitrate, hydrogen sulfide and other contaminants.

The facility also initially released a more toxic form of selenium into the environment even as it reduced total selenium concentrations in treated water. The company has since addressed the issue with an additional layer of treatment.

Now it seems Teck may have had similar issues with another treatment facility as well, Sexton said after reviewing a July 2022 briefing note obtained by The Narwhal through a freedom of information request.

But it’s difficult to know for sure, Sexton warned. “We’re not getting the data to look at and draw our own scientific conclusions, we just have to infer from what Teck is reporting to the province,” she said.

The document, prepared for the deputy minister of Environment and Climate Change Strategy, notes the treatment facility, which relies on saturated rock fill technology, was operating at reduced capacity because elevated selenium levels had been detected in bottom-dwelling invertebrates downstream of the outflow.

Teck has touted its saturated rock fill technology as a “breakthrough in passive water treatment technology.” The technology, which uses existing mine infrastructure, is a less costly alternative to its tank based active water treatment facilities. Both treatment options rely on bacteria to treat selenium and nitrate.

For Petryshen, the issues mentioned in the briefing note underscore the fact that Teck’s saturated rock fill technology is still “in development.”

“It still needs more research and it’s not this sure-fire solution that maybe Teck or the province want it to be,” he said.

“They can’t just rely on this one new technique in the future,” he said. “They do need to be spending money on redesigning these waste rock dumps.”

Teck did not respond to The Narwhal’s detailed questions about the issues with the saturated rock fill treatment facility, offering instead a general statement about efforts to address water quality.

The B.C. government did not respond to The Narwhal’s questions by publication. The Narwhal was directed to the Elk Valley Water Quality Hub, which notes the Elkview Operations saturated rock fill started treating water from Erickson Creek again in October “after this source was offline for maintenance and aquatic health investigation since April.”

There are longstanding concerns both in Canada and the U.S. about a lack of transparency around water pollution from the Elk Valley mines.

“We get this filtered, cherry-picked information that comes from the company, reporting to everyone how they’re doing in the watershed and if you ever want to look at anything more closely, none of that information is available,” Sexton said.

It’s one of the reasons behind longstanding calls for the issue to be referred to the International Joint Commission, a Canada-U.S. body established under the Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909 to address disputes in transboundary watersheds. .

But internal government records show Teck and the B.C. government lobbied against involving the International Joint Commission.

The issue of water pollution from Teck’s mines recently garnered attention from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and President Joe Biden, who committed last month that the two countries would reach an agreement in principle this summer to reduce pollution in the watershed.

Petryshen and others want to see the International Joint Commission included in that agreement.

“B.C. hasn’t done a good job in dealing with this issue,” he said. “We do need someone else to actually get in charge of the reins.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...