Hope for a huge, ancient and imperilled fish

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

This story is part of In the Line of Fire, a series from The Narwhal digging into what is being done to prepare for — and survive — wildfires.

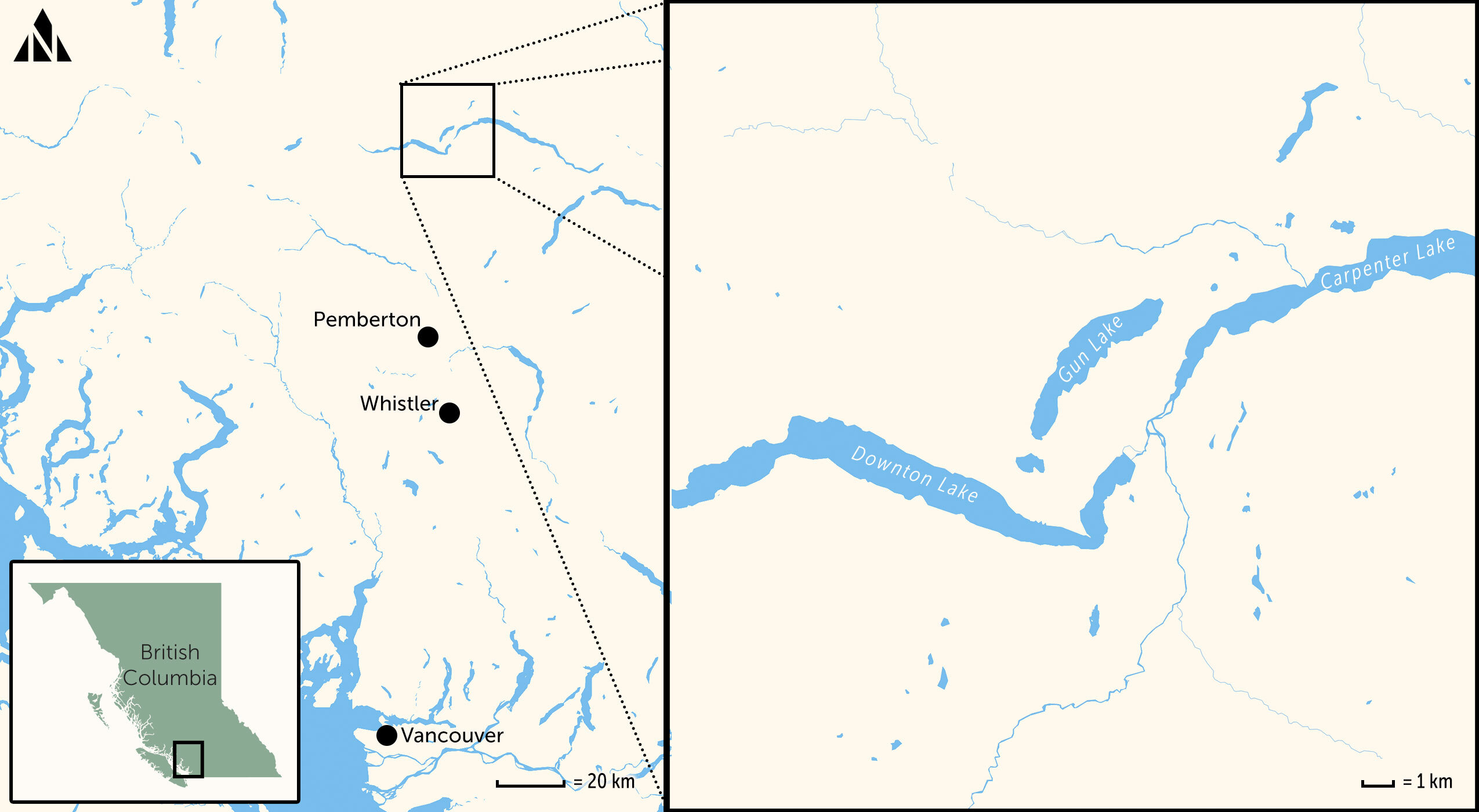

It’s not quite 7 a.m. and Michelle Nortje is engaged in her daily ritual, hiking the switchbacks and curves of the trails in the woods behind her house on the water’s edge of Gun Lake, about 100 kilometres north of Whistler, B.C.

Her dogs — two giant Alaskan Malamutes, Grizz and Slim — amble beside her. The colour of their thick coats, in variants of white, brown and pitch black, matches the newly burned forest surrounding Nortje.

Last summer, the out-of-control Downton Lake wildfire devoured the forests behind Nortje’s lake-side home, burning almost 10,000 hectares. It destroyed 43 properties and damaged 11 others. Within a week, Nortje was out searching for her trails. “At first it was hard,” she says.

In the sand-like soil she saw trees that were burned but still standing. Slowly, she began to make out her favourite paths. “The trees that were landmarks are still there,” she says, pointing towards a big fir tree at the edge of the fire zone wearing a hat of green needles above its burned trunk.

At the edge of Nortje’s property, several trees bear a flash of red. Strips of dusty red flagging tape say “cutblock boundary” in capital letters. To Nortje, it’s a sign the forest’s upheaval may have just begun.

Nortje’s rural neighbourhood is in the crosshairs of a relatively new industry in B.C., as logging companies set their sights on the burn zones of B.C.’s string of record-breaking wildfires.

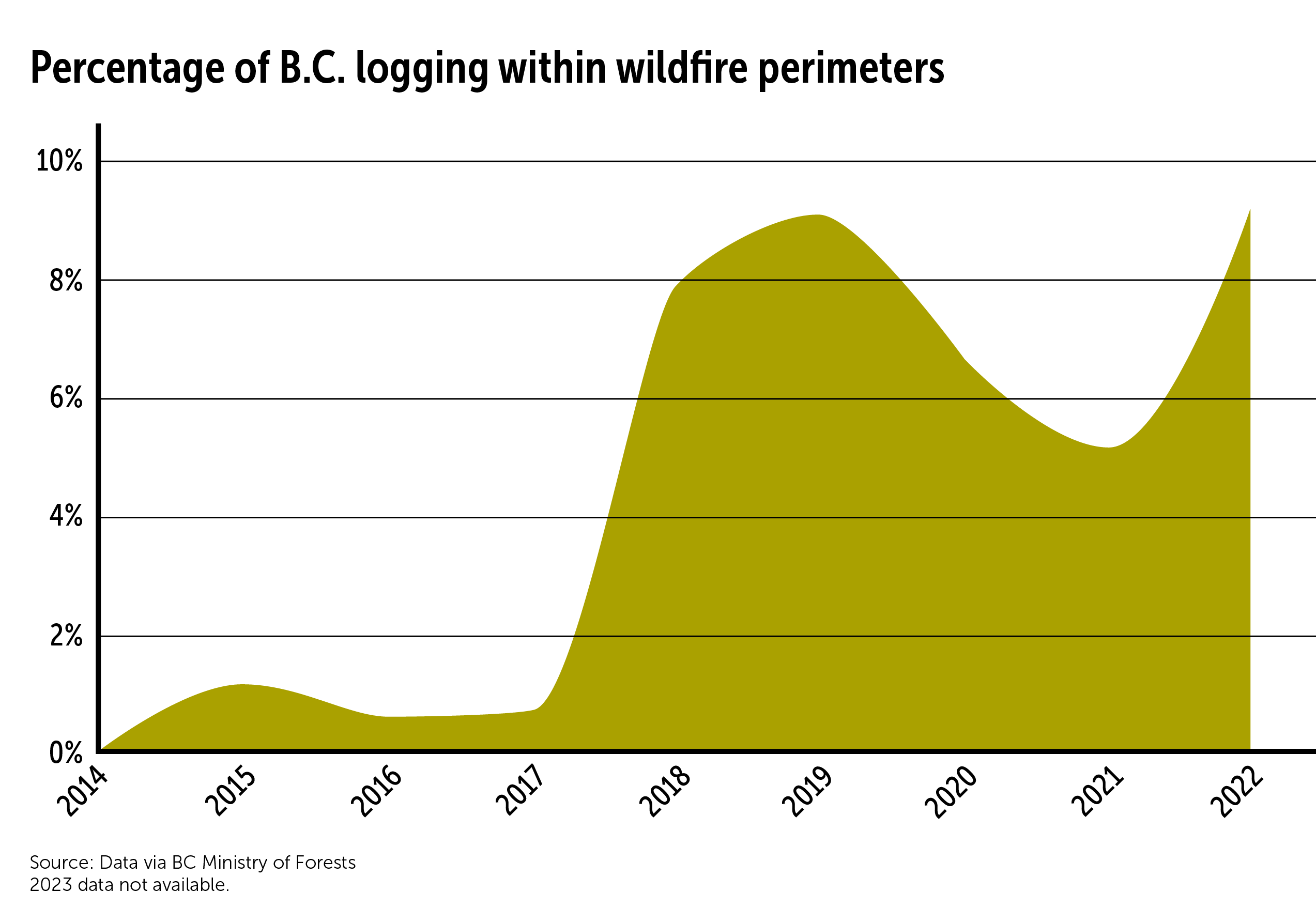

The industry, known as “wildfire salvage,” is on the rise. In almost every year since 2018, logging cutblocks in five wildfire zones in B.C.’s Interior were each larger than the land-mass of the city of Vancouver, according to The Narwhal’s analysis of provincial data. According to an email from B.C.’s Ministry of Forests, wildfire salvage logging in 2022 made up about 10 per cent of the province’s annual cut — a 100-fold increase over the past decade.

In B.C., wildfire salvage typically means clear cutting a burned area. Salvage logging offers an opportunity for companies to access discounted wood at a time when the forest sector is in crisis following a century of industrial logging, wildfires and the spruce beetle and pine beetle infestations. As mills close around the province and workers are laid off, the B.C. government has announced policies to expedite wildfire salvage logging, making it cheaper and faster for companies to harvest in burn areas.

But “salvage” is not always the right word. B.C.’s logging rules allow companies to harvest living trees in wildfire zones. The Narwhal’s analysis of provincial data for active logging in five wildfire areas in B.C.’s Interior found more than half the logs harvested — including from old-growth forests — were classified as construction grade, meaning they could have come from trees that survived the fire.

Biologists say trees in burn zones can offer rare islands of habitat for wildlife, including species at risk of extinction like spotted owls and caribou. And even when dead or dying trees are harvested, salvage logging can also pose risks to biodiversity, soil health and water systems.

“All this natural regeneration is starting,” Nortje observes. “If you come in with your heavy machinery and stir all that up, how is that good for rehabilitation?”

Salvage logging is a familiar practice in B.C. forests under stress; it was the primary way B.C. responded to the pine and spruce beetle infestations, leading to a sharp spike in the volume of trees companies could log in the province’s north and southern interior. Logging levels increased by about one-third overall, with a heavy focus on pine trees. Now, as beetle infestations subside, wildfire salvage is the new game in town.

“We are working hard to remove barriers and expedite wildfire salvage,” the B.C. Ministry of Forests explained in an email to The Narwhal.

B.C.’s forests are no stranger to fire. In damper places like the temperate rainforests on the coast and the interior wet belt, fire has been an infrequent guest, burning rarely and in lighter patches. To the north, in forests of spruce and pine, fires historically come more often and engulf larger areas.

But many species and ecosystems evolved in tandem with fire and benefit from a landscape left undisturbed after a burn.

Lodgepole pine trees produce special, waxy cones that wait for the melting power of wildfire to release their seeds. And while fire generally takes a toll on forest soil, it also provides nutrients from the carbon of combusted plant life, helping catapult a succession of plants and shrubs into growth. Burned, dead trees play an integral role in ecosystems, providing nesting spots for birds like tree swallows, holding water in the soil and shielding the earth from the drying effects of wind and sun.

Fire zones get another leg up in the recovery process from the places where green trees remain. These patches might lie in wet gullies, or they might have been spared from the blaze thanks to a lucky gust of wind. Sometimes green zones are found in old-growth forests, where big trees’ thick bark protects them from what would otherwise be a fatal burn. Either way, green trees in fire zones can offer refuge for a plethora of wildlife and a jump start for regenerating the burned forest next door.

“It can be in their DNA that they’ve withstood the fire,” fire ecologist Kira Hoffman says in an interview. “They can have species that are going to be really good at creating the next generation of forest.”

Added together, that mixture of dead and living forest is known as the fire’s “biological legacy.” It’s akin to a shock absorber, cushioning the forest’s landing after a fire blow and increasing the chances biodiversity — the mix of different living things in an ecosystem — makes it through.

Experts say salvage logging has the potential to remove nature’s shock absorbers just when forests need them most.

“All of the things that we want to see in our forests become really hard after you’ve salvage logged,” Jesse Zeman, executive director for the B.C. Wildlife Federation, tells The Narwhal.

Predation is one example; species like elk and moose have been shown to avoid salvage-logged areas to avoid getting picked off by predators like wolves, which capitalize on the easy access afforded by logging roads. Salvage-logged forests may also possess fewer of the smaller species that together make significant contributions to biodiversity; a 2017 study found eight out of 24 species groups experienced “significant decreases” in population following salvage logging. Lichen, bird and beetle species fared the worst. Black-backed woodpeckers, for instance, favour burned trees for nesting.

According to Phil Burton, a biologist at the University of Northern British Columbia and co-author of the study, losses are particularly pronounced if salvage logging targets rare ecosystems remaining in an area — for example, a burned old-growth forest surrounded by young, logged stands.

If those older forests are clear cut for salvage, species that relied on their rich assortment of decaying wood may have nowhere to go. Longhorn beetles, for example, covet the dead wood that fires provide; some have sensors that detect smoke from far away. Salvage logging in southwest Oregon was shown to damage habitat for northern spotted owls, who nest only in big, old trees.

Salvage logging can also change the way water moves through the forest. “Once you go in and salvage-log a big cutblock, the wind hits the ground and it dries the soil right out,” Zeman says. When water hits salvage-logged ground, it can take the soil’s structure and nutrients with it as it flows away.

A study of wildfire salvage in the Rocky Mountains in Alberta found salvaged watersheds had 37 times more sediment in their water than unburned watersheds — and 28 times more than forests that burned but weren’t salvage-logged. That sediment can suffocate fish eggs and transport pollutants. The study found some areas had not recovered after 11 years.

B.C.’s former chief forester Diane Nicholls cited those findings and others in a 2018 guidance document for forest professionals. “Beyond the effects of the wildfires themselves, the potential negative effects of post-fire salvage on some ecosystem values may be difficult to remediate,” Nicholls wrote. She said salvage logging impacts “may require long timelines for remediation (i.e., decades) or they may be irreversible in the context of forest management time horizons.”

Nicholls called for “an environmentally focused and cautious approach” to planning salvage logging, saying companies should create plans that prioritize which trees to leave.

“Live trees must be left on the landscape, wherever possible, even if they are within the [timber harvesting land base],” Nicholls wrote.

She also noted the potential for damage to soil and water resources is high. It may be more effective and less expensive to protect source water than to deal with the impacts of salvage logging through “increased levels of post-logging rehabilitation,” she said.

But Nicholls’ guidance has no legal teeth.

In an email in response to questions from The Narwhal, a spokesperson for the Ministry of Forests said it does not have regulations that compel companies to address the ecological risks of salvage logging.

The province also doesn’t require companies to leave live trees in burn zones, the ministry said. Nor does the B.C. government track how many live or green trees are logged within wildfire zones.

“They’re not actually mapped in terms of what percent of trees remain alive,” Burton says, adding better salvage data “is important for conservation as well as timber supply protection.”

But B.C.’s Ministry of Forests does keep tabs on the quality of wood that companies log.

Of the salvage logging data The Narwhal analyzed from active cutblocks in the five wildfire areas, 16 per cent was classified as “grade 1,” or premium-grade logs, meaning the logs were mostly undamaged. To qualify for that high-value grade, at least three-quarters of the log must be undamaged by fire or other impacts.

Because they’ve sustained such light damage, these trees are the most likely to still be alive and green.

Of the trees included in The Narwhal’s analysis, nearly half were classified as “grade 2,” or construction-grade timber. Up to half of this grade of tree can exhibit damage from impacts like fire. Because B.C.’s grading system isn’t fire-specific, even construction-grade logs can be green and unburned but have other subtle issues such a curve in the wood or a knot.

Burton says trees in either of these grades may either live or die following a fire. “It’s important to distinguish between scorching and charring,” he says. A “scorch” just makes it into bark’s more superficial layer, while “char” means the burn went deeper into the wood’s living layer.

That’s why trees with thick bark, like old-growth Douglas fir and Ponderosa pine, tend to have better odds of surviving a fire. Sometimes even charred trees can survive if a fire blazes through quickly, burning only one side of the tree.

Even if trees eventually die from fire damage, Burton says they can play a key role in the ecosystem during the years they still stand.

“That’s more or less intact solid wood,” he notes.

A loophole in B.C.’s wildfire salvage logging rules means forestry companies can often get premium wood at a substantial discount.

The loophole is tied to the way B.C. calculates “stumpage” — the fee companies pay to the government for logging trees on public land, also known as Crown land.

As long as some wood in a cutting area in a wildfire zone is considered to be “fire damaged” — ranging from mild, superficial burning to severe charring — logging companies can qualify for salvage stumpage rates for the entire area. Those fire-damaged areas can include patches of green trees. The discount increases for every 10 per cent of the stand deemed to be fire damaged, meaning high-value, live trees can be logged at a lower stumpage rate. Sometimes that adds up to a significant discount.

Tolko Industries is one of an unknown number of companies engaged in salvage logging in B.C. This year, the Narwhal’s data analysis found one of Tolko’s salvage cutting permits in the White Rock Creek fire zone, near Vernon, B.C., paid just 25 cents per cubic metre — a cubic metre is roughly an average wooden phone pole — for the mostly construction-grade live wood the company harvested from the burn zone. That’s around $10 per logging truck — 99 per cent less than the rate Tolko would pay for trees just outside the burn zone.

“One might question whether B.C. citizens are getting fair value for the cutting of largely sound public timber,” Burton says.

Tolko did not respond to The Narwhal’s request for comment.

Typically, the 25-cent rate is reserved for the lowest-quality wood — trees “only good enough for pulp or worse,” according to Chris Gaston, associate professor of markets and economics at the University of British Columbia’s faculty of forestry.

In an email, the Ministry of Forests said the stumpage in a fire-damaged stand is calculated “based on the amount of damage in the stand as a total,” adding, “it would not be feasible to try and calculate damage based on individual logs.”

Companies are often fined for leaving wood waste on a cut block. But in the case of fire salvage, wood “burned to a point that it can no longer be used to manufacture forest products” is not considered to be waste, according to the province’s fire salvage pricing guidelines. That means companies can access a salvage discount for clear-cutting in a highly burned area, without any consequences if they leave behind piles of severely burned logs.

Zeman says the stumpage rate incentivizes companies to double down on the last remaining green trees in a fire zone. “If you’re getting a discounted rate on green stuff, you’re probably going to focus on those spots,” he says.

A pricing loophole known as the “grade 4 credit” system can also increase the amount of green wood companies are allowed to salvage log. That’s because companies receive credit for the beetle-killed or burned wood they bring to certain kinds of mills. Those credits allow them to log an equivalent amount of green wood without affecting their annual logging quota, known as their allowable cut.

Major licencees logging in their own tenure areas are also exempt from B.C. rules on cutblock size, meaning salvage logging clearcuts can be bigger than unburned ones. Additionally, they receive an exemption from “adjacency” rules that generally prevent companies from lining up cutblocks next to one another.

Zeman sees room to curb some of salvage logging’s worst consequences by leaving the green trees and big, burned trees and harvesting the smaller ones. He also wants to see companies log during the winter months to reduce damage to soil.

“Is there a better way to do it? The answer is yes,” he says. “Are we doing it a better way? The answer is no.”

B.C.’s non-legally binding guidelines on salvage aren’t enough to change companies’ behaviour, particularly when they’re competing against one another to produce cheaper wood, Zeman says.

“Unless you have laws and regulations that say, ‘This is how we do it,’ and unless you have enforcement of those laws and regulations, it’s meaningless. ”

B.C.’s policies on salvage logging are changing, but some say it is not for the better.

Last year, B.C. released an updated version of Nicholls’ salvage guidance. It removed most of the references to “retention planning,” along with Nicholls’ advice to leave live trees standing.

The Forests Ministry says its new guidance “remains consistent with previous years,” noting, “the guide was streamlined and updated to assist licencees in implementing salvage operations.”

Over the past year, the B.C. government has announced a series of policy changes that make it faster and easier for companies to access salvage logging licences. “We need to get the licences out and get the work done and the replanting beginning as fast as possible,” Forest Minister Bruce Ralston explained during budget debates.

Ralston’s ministry says wildfire salvage logging helps reforestation efforts.

“Removing burnt wood and reforesting quickly allows new trees to grow faster, decreasing the amount of time the site is without tree cover and increasing the hydrologic recovery of the site,” the Forests Ministry wrote in an email to The Narwhal.

But an internal briefing note, released through a freedom of information request, complicates the picture.

Severely burned forests can sometimes benefit from tree-planting to trigger regrowth, says the briefing note, prepared for Ralston in September 2023 by Forests Ministry advisor Garrett McLaughlin. The note says “salvage operations may damage natural regeneration” in forests not as severely burned by wildfires.

B.C.’s salvage logging rules for major forestry licencees don’t distinguish between heavily burned forests and lightly burned forests. “Major licencees are not required to only log in areas of moderate or severe burn intensity,” the forests ministry clarified in an email.

Even in highly burned areas, the briefing note warns against clear-cut salvage logging. “The standing dead canopy can enhance regeneration capacity,” it says, adding in some cases “underplanting” new trees beside dead ones might be a better option.

But safety concerns make that difficult, Hoffman points out. “The problem is when you go in and replant something, you actually have to take away the overhead hazards,” she says, adding that sometimes intensely burned earth can’t support planted trees anyway.

Hoffman’s solution is to consider letting the forest grow back on its own. “Nature will do its thing to recover,” she says. “Planting should be very intentional, and should not always occur in some places.”

In some severely burned regions, soils have been depleted and evergreen trees might not grow back for decades. That means tree planting could fail, Hoffman says, pointing out that intensely burned forests will often reseed themselves naturally. “These seeds are more likely to be resistant to future fire.”

According to an email from the B.C. Ministry of Forests, salvage logging can reduce “the risk of wildfire impacting these stands in the future.” Wildfire ecologist Robert Gray disagrees with such blanket claims. “If they use the term salvage in its traditional sense then no, you’re not really reducing the risk,” he says.

“You may be exacerbating it.”

In areas that have historically experienced low-intensity, frequent wildfires, such as the dry forests of B.C.’s southern Interior, Gray advocates for removing the small stuff — younger trees and brush — to reduce the risk of “reburn” where a fire burns hotter, and more intensely, a second time. But he says taking out the bigger trees, which are often more fire-resistant, doesn’t add up.

“Just wholesale going in there and taking out the large trees, leaving a mess behind, that’s not going to help you answer that question of what happens if this burns again.”

According to Darlene Vegh, a Gitanyow Elder and fire expert, salvage logging on the burned forests from the 2018 Mill Lakes fire, north of Kitwanga in Gitanyow territory, led to big build-ups of dead wood and debris. The fire burned about 360 hectares, but didn’t lead to any evacuations. “Now there is more fuel build-up there than there ever was before.”

“We checked it out this summer and nothing is growing there,” she says. “Very few things are making their way through that.”

So far, the burned forests above Nortje’s house remain unlogged, but salvage logging is well underway nearby. Private lots close to Nortje’s cabin have been clear cut to the lake’s edge. Northeast of Gun Lake, the fire’s first four commercial salvage cutblocks are complete; fresh clearcuts dot the burned hills.

Much of the salvage logging in the area has been carried out by Lillooet-based Interwest Timber. On commercial cutblocks, the company is working in partnership with St’át’imc Tribal Holdings, a company it manages on behalf of six co-owning members of St’át’imc Nations.

Travis Peters, lands manager for Xwist’en First Nation, a co-owner of St’át’imc Tribal Holdings, says the current cutblocks are an improvement over earlier proposals put forward by Aspen Planers, which owns mills in the region. “They roped in too many green stems,” he says, referring to the green trees the companies wanted to include in their salvage logging plans.

Scott Fiddick, a development manager at Aspen Planers, tells The Narwhal the company is now in the process of proposing new salvage cutblocks in the region and is incorporating feedback from local nations.

Peters says the nation has told Interwest to leave the remaining green trees standing, and to log only in the more severely burned areas.

He’s hopeful salvage logging can help replant Douglas fir trees on which mule deer — a key species for the nation that is in decline — rely on for food and shelter.

“If we’ve done it right, we’ll get rid of the licorice sticks and get the trees growing back,” Peters says.

According to B.C.’s forest billing database, 88 per cent of the salvage wood logged by Interwest for Stat’imc Tribal Holdings was sawlog-grade lumber. Of that, 26 per cent was the highest grade lumber — from trees most likely to survive the fire. Thick-barked Douglas fir is a dominant species in the area’s forests. And one of the logged cutblocks overlapped an area recommended for deferral by B.C.’s old growth technical advisory panel.

The company has other cutblocks pending.

According to Mike Carson, Interwest’s forest manager, the company is logging only in highly burned areas and isn’t cutting live or green trees in the wildfire zone.

The salvage logging underway leaves Gerald Michel, lands and resources liaison with Xwist’en, with many questions. “The research I’m reading is saying, ‘Leave it alone, let it regrow on its own,’ ” he says. He’s been unhappy with previous salvage operations carried out by Stat’imc Tribal Holdings and Interwest, saying it resulted in too many big, old trees being logged. This time, Michel has been on the ground at Gun Lake, telling Interwest which areas he’d like the company to leave intact. “We’re trying to lessen the impacts of salvage,” he says.

“The downfall, basically, is that it [salvage logging] has to be a money-maker.”

Companies like Interwest face a predicament when they salvage — leaving the biggest, healthiest trees on the block might be better for the forest, but it means fewer profits.

“For now, we’re keeping everyone working,” Chris Graham, from Interwest, which employs about 40 people from the Lillooet area, tells The Narwhal.

Interwest is focusing on the burned trees while trying to bring in some profit, Graham says. “You’re not going to go into stands that lose money, unless governments can fund that kind of thing.”

New rules for fire salvage may be on the way.

“You’ve got everybody in the room right now,” BC First Nations Forestry Council’s chief executive officer Lennard Joe says in an interview. He’s a member of the province’s newly formed wildfire salvage leadership committee, which brings together government specialists, the First Nations Forestry Council and representatives from the forest industry to make recommendations on how companies should salvage log and to oversee their implementation. “If there were rooms like that before, First Nations weren’t at that table,” he says.

After the “economic net-return free-for-all” of B.C.’s pine beetle salvage logging operations, Joe is hopeful these processes signal the coming era of fire salvage will be different. “You’re going to see legislation crossing the floor to develop policies, acts and regulations that will reflect how we’re moving forward,” he says.

In some cases, Joe thinks salvage logging could reduce pressure on areas unharmed by wildfires and financially support wildfire recovery, from tree planting to rebuilding infrastructure.

“It’s got to be site sensitive,” he says. “You’ve got to manage a prescription that brings back the best forest.”

Back on the trail, Nortje reaches out to inspect the newest pops of green bursting through what looks like ashen sand dunes on what used to be the forest floor.

Next to yarrow and wild rose, Nortje holds the green leaf of a spirea plant. “It’s really not that attractive,” she says. But fire has given Nortje a new appreciation for unassuming things. “It’s now the rockstar plant, because it’s just everywhere.”

Nortje has been documenting the forest’s recovery by sharing photos in a Facebook group shared with residents in the community. “It’s amazing how fast stuff comes back,” she says. “Their root systems are still there.”

As she passes by strips of red flagging tape marking new cutblock boundaries, Nortje worries about sliding backwards. “I just think this disaster is so big,” she says.

“Is salvage logging going to make it an even bigger disaster?”

Updated on Aug. 14 at 1 p.m. PT: This story has been updated to correct the number of hectares burned in the Downton Lake fire in 2023. The number of hectares burned was 10,000, not 1,000 as previously stated.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. Angello Johnson’s shoulders burn, and his arms...

Continue reading

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

We’re excited to share that an investigation by The Narwhal is a finalist for the...

A new documentary, Nechako: It Will Be a Big River Again, dives into how two...