The Narwhal’s in-depth environmental reporting earns 11 national award nominations

From disappearing ice roads to reappearing buffalo, our stories explained the wonder and challenges of...

Biologist Rob Serrouya received word of the female caribou’s possible demise at 8:20 a.m. one Monday in late November. An automated email message warned the caribou’s radio collar had slipped into mortality mode, meaning no signals of movement had been transmitted through a satellite for six hours.

Serrouya doubted the relatively new collar had malfunctioned or was lost in the snow on the slopes of the Monashee Mountains, north of Revelstoke, B.C. Likely something else had happened to the caribou from the highly endangered Columbia North herd. He grabbed his cell phone, a knife, a spot safety beacon and a telemetry receiver.

Two hours later, a helicopter dropped Serrouya off on a sloping patch of open snow in the forest of Engelman spruce and subalpine fir. He snowshoed about 900 metres through the trees, towards the collar’s signal. The snow was unusually shallow, barely a foot deep, for that time of year. “Not a good sign,” he thought. Then he saw a mess of flattened bushes and broken branches and instantly knew he was dealing with a battle scene.

Serrouya is co-director of the Wildlife Science Centre for Biodiversity Pathways, which collects scientific data on species and their habitats to inform decision-making. For more than two decades, he has tracked the Columbia North herd. The herd makes its home in the Kootenay region in southeast B.C., migrating seasonally from the old-growth valley bottoms of the rare inland temperate rainforest to snowy alpine meadows in the Monashee, Columbia and Rocky mountains. It’s one of B.C.’s deep-snow caribou populations, a moniker conferred because during late winter the caribou access hair lichens growing on trees in subalpine forests by walking on top of metres-deep snow.

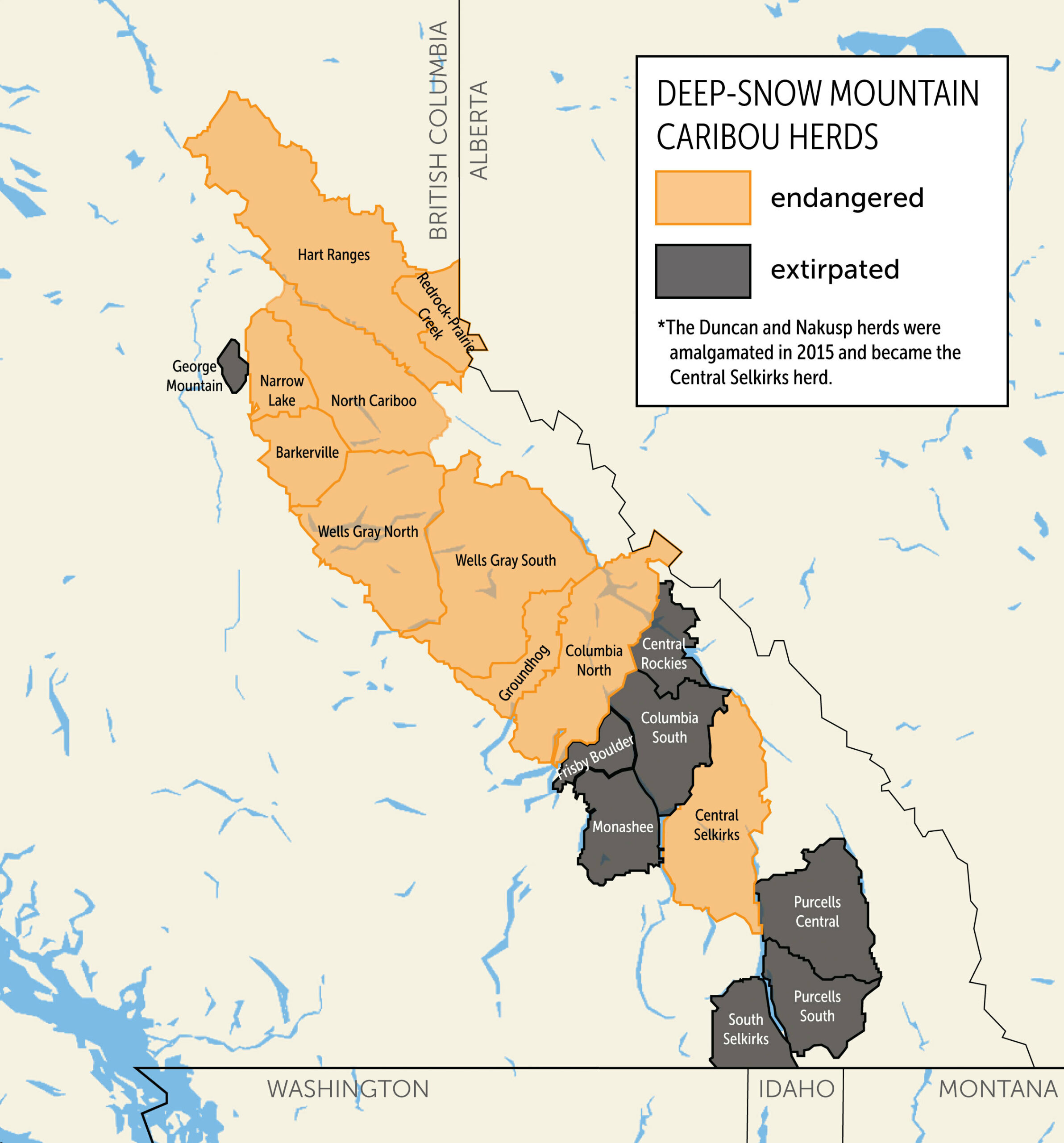

Over the past 15 years, a calamity has befallen B.C.’s deep-snow caribou — a caribou ecotype found nowhere else in the world. In 2005, B.C. had 18 deep-snow caribou herds. Today, only ten remain. All are on the cusp of local extinction. Nine deep-snow caribou herds once lived to the south of the Columbia North herd. Eight are gone. Only about two dozen animals remain in the ninth herd, an amalgamation of two herds. Bucking the dispiriting trend, and following costly interventions such as shooting wolves, in 2022 the Columbia North population grew by almost two dozen, to 209 animals.

Make that one fewer, Serrouya thought, as he surveyed the blood-stained ground. Near the base of a spruce grove, etched in the snow amidst large and small broken branches, were drag marks, as though a toboggan had been pulled along. “The poor gal put up a good fight,” Serrouya recalls. “She battled hard.” Most of the caribou’s furry brown body and an arc of ribs poked up from the snow. Only internal organs, including the liver, were missing. Serrouya pulled out his knife and pared back the flesh on the caribou’s rump; the fat was more than one inch thick. She wasn’t a poorly nourished animal heading into winter. “She was in great shape.”

Wolf tracks, with four symmetrical toes and claw marks, made a beeline to what looked like a wolf bed hollowed out in the snow. The wolf, or possibly a pair of wolves — Serrouya saw no signs of a pack — could still be nearby. A wolf might even have watched him as he unfastened the caribou’s collar, tucking it into his backpack.

The wolves had almost certainly accessed the Columbia North habitat through an extensive clear-cut on the privately owned and managed Beaumont lands immediately to the east, a conduit to the alpine where caribou would normally be secure. Wolves follow moose and deer into newly logged areas, conserving energy by travelling along linear disturbances such as logging roads and seismic lines.

Climate change deals a double whammy: a deeper snowpack would have prevented wolves from accessing the slope where the caribou lay. “Had it been a normal snow year, it would have been very unlikely that the wolf could have been traveling at such high elevations,” Serrouya says.

Perhaps no other animal highlights Canada’s role in the planet’s unfolding sixth mass extinction event as much as caribou, the species engraved on the Canadian quarter. Worldwide, more than one million species face extinction, according to a 2019 United Nations report. In Canada, one in five species are at some risk of disappearing.

Caribou are in trouble across the country, following decades of industrial logging, mining, oil and gas development, hydro dams, road-building and motorized backcountry recreation in their habitat. “Generally speaking, the picture is still quite grim,” Justina Ray, Wildlife Conservation Society Canada president and senior scientist, tells The Narwhal.

Ray says we know how to save Columbia North caribou and other deep-snow caribou herds from local extinction — just as we know what actions to take to thwart climate change. But governments lack the political will to save caribou, she says, as they also lack the gumption to slash carbon emissions to safe levels. And as with climate change, the conundrum is that the longer we wait, the more difficult, expensive and painful the action becomes.

Monitoring the Columbia North population — including the purchase and deployment of radio collars — cost the provincial government $70,000 last winter, according to an email from the B.C. Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship. In 2022, the government spent $119,000 to shoot three wolves and five cougars in Columbia North habitat, from a province-wide $1.7 million budget for caribou “predator reduction.” In 2021, the government spent $112,000 to kill six wolves and four cougars in Columbia North habitat, out of a $1.4 million province-wide budget.

The B.C. government also invested in a $2.4 million pen for pregnant females from the Columbia North herd, who were tranquilized and transported to the enclosure by helicopter and skidoo. The pen was shut down after three adult caribou died and two calves sustained injuries and were euthanized. That didn’t stop the government from spending about $360,000 on a new maternal pen that began operations last year in a desperate effort to save the only other caribou herd left in the Kootenay region — the Central Selkirks population, with only 28 animals remaining. (Project partners spent an additional $200,000 in in-kind time and equipment.) The pen, funded by First Nations and non-governmental organizations as well as the government, has a first-year operating budget projection of $290,000, according to the ministry.

Studies show such interventions can stave off near-term extirpation — local extinction — for herds in rough shape like the Columbia North population. But while extreme measures buy time, Ray and other biologists say they are not a solution if habitat destruction continues simultaneously. “We’re nullifying the problem on the one hand but we’re still continuing to create the problem on the other,” Ray observes.

Last spring, the conservation group Wildsight discovered an approved cutblock in the Wood River basin, north of Revelstoke, in the Columbia North herd’s critical winter habitat — habitat the federal government deems necessary for the herd’s survival and recovery. The group also documented numerous other cutblocks overlapping Columbia North herd critical habitat. Many cutblocks were auctioned by BC Timber Sales, a government agency that manages about 20 per cent of the province’s annual allowable cut.

In November, Wildsight sounded the alarm about plans to clear-cut more of the herd’s critical habitat, in the Seymour River watershed north of Revelstoke, in an area biologists refer to colloquially as the “hub” for the Columbia North caribou because herd members spend so much time there. Wildsight tallied up 620 hectares of clear-cuts — a total area larger than one-and-a-half Stanley Parks — planned in the herd’s habitat in the rare inland temperate rainforest, a highly endangered ecosystem.

The clear-cuts were planned despite a request from Splatsin First Nation for a moratorium on logging in Columbia North habitat, in the nation’s territory, until herd planning is complete. Led by the B.C. government, the herd planning process aims to identify activities to reduce the decline of individual herds and restore habitat.

“It’s really a frustrating state of affairs,” says wildlife biologist Corey Bird, who works for Yucwmenlúcwu (Caretakers of the Land) LLP, Splatsin Development Corporation. “Caribou require a functioning ecosystem, not just old trees … It really kind of boggles the mind that we’re able to continue to impact habitat.”

Trina Antoine, Splatsin title and rights cultural liaison, recounts how caribou were once so numerous in the nation’s territory it took four hours for the animals to pass. Caribou were essential for the Splatsin and other Indigenous nations, she explains. The thick hides were tanned to make hardy, waterproof footwear, and animals were harvested in the late summer when meat held a high fat content.

Today, Splatsin members don’t know what caribou meat tastes like, Antoine says. “How we go hunting now is the IGA and SuperValu. Back then, the refrigerator was the land. If people were hungry they just had to go outside and they could find their food, whether it was through foraging or game or fish.”

According to knowledge gathered from Elders, the demise of caribou in Splatsin territory began in the 1920s after thousands of miners flocked to the area and needed to be fed. Construction of the Mica and Keenleyside hydro dams dealt another blow, impeding caribou migration routes and flooding old-growth forest habitat. Recreational vehicles such as snowmobiles and ATVs — and alpine activities such as heli-skiing — also disturb caribou, Antoine points out. “People won’t leave well enough alone. They have to develop every little place, every space that’s available. Nobody can leave places for the wolves to be, for the caribou to be, for the grizzly bear to be.”

Speaking for herself and not for the nation, Antoine says it’s easy to make wolves the scapegoats. “When it really comes down to it … this is not a wolf problem. This is a human problem. These caribou didn’t disappear because of wolves. They disappeared because of the destructions that we have put upon them.”

In 2020, to stave off an emergency order under Canada’s Species at Risk Act, the B.C. government signed a much-touted caribou recovery “framework agreement” with the federal government.

The agreement came after the environmental law charity Ecojustice, acting on behalf of four conservation groups, asked the federal government to invoke emergency powers under the Act to save the Columbia North herd and other imperilled B.C. caribou populations. Emergency powers grant Ottawa responsibility for decisions that are normally provincial jurisdiction, such as whether to issue logging permits in critical habitat for endangered caribou herds.

“The current situation with southern mountain caribou is dire,” Ecojustice told then-federal Environment Minister Catherine McKenna in 2018. “After years of federal delay under SARA [the Species at Risk Act], and in the face of B.C.’s ongoing failure to protect the species and its habitat, this species needs immediate action to ensure it can survive and recover.”

The framework agreement referenced somewhat vague commitments to protect and restore habitat, manage predators, institute maternal pens and captive breeding, monitor populations and incorporate Indigenous Knowledge into recovery efforts.

Almost three years later, Bird says framework agreement discussions are moving at a “very slow pace.”

“We’re feeling very frustrated at the pace at which discussions are occurring and any foreseeable change in what’s happening on the land,” he says. “It’s hard not to feel like the efforts being made in some ways are lip service.”

Eddie Petryshen, conservation specialist for the non-profit group Wildsight, questions whether the framework agreement has helped the Columbia North caribou. “The province and the federal government have committed to recovering caribou, but so far all we have seen is a plan to make a plan,” Petryshen says. “Right now it’s business as usual on that landscape … There’re places that are extremely high-value caribou habitat that have been logged in the past three years, while that agreement was in place.”

To illustrate his point, Petryshen emails The Narwhal photographs of core Columbia North herd habitat that was clear-cut after the agreement was signed. One photo shows a logging road surrounded by felled trees in an area known locally as the Devil’s Garden, about 90 kilometres north of Revelstoke, in the transition zone between old-growth cedar and hemlock forests and sub-alpine forests of Engelmann spruce and fir. The clear-cut was part of the old-growth deferral areas announced in November 2021 by the B.C. government to protect forests at the highest risk of biodiversity loss. It went ahead after the deferrals were announced, ostensibly because it had been pre-approved.

A second photo shows a clearcut in a “beautiful, spectacular big old-growth valley bottom,” in core Columbia North herd habitat in the inland temperate rainforest, about 110 kilometres north of Revelstoke. Petryshen says the area was logged in the winter or spring of 2021.

Two aerial photographs Petryshen shot from a small float plane during a bumpy, three-hour ride depict a landscape fractured by multiple clear cuts, zig-zagging logging roads, a hydro line corridor and the Revelstoke hydro reservoir, all in Columbia North herd habitat. One photo shows a brown square in the herd’s habitat, all that remains of what Petryshen describes as a “beautiful, ancient forest” that was logged in the fall of 2021.

The B.C. government says 35 per cent of the Columbia North herd’s habitat is “protected” in parks and other designations such as ungulate winter range. Yet 65 per cent of the herd’s habitat remains open to logging, mineral exploration and other cumulative impacts such as recreation and heli-skiing, Petrynshen points out. “Decades of science has shown that caribou need vast swaths of intact forest in order to survive. The vast majority of their habitat needs to be undisturbed or minimally disturbed.”

B.C.’s 2007 mountain caribou recovery plan aimed to protect 95 per cent of winter range for caribou. But Petryshen says that didn’t happen in the Columbia North herd habitat, where the majority of caribou winter range remains unprotected and open to logging and road building. Most habitat loss from logging in recent years has occurred in low elevation ranges where the herd spends upwards of half the year in old-growth cedar-hemlock forests, Petryshen notes. “You don’t need to look far to see how the status quo is failing caribou,” he says, pointing to all the extirpated herds in the Kootenay region.

Trevor Goward calls government-sanctioned logging in core caribou habitat “designer extinction.” Goward is a lichenologist with a particular interest in B.C.’s deep-snow caribou herds, which rely on nutritious arboreal hair lichen for sustenance in wintertime. The lichen grows only in sufficient quantities on old-growth trees, money-makers for the logging industry.

Goward has been monitoring the deep-snow Wells Gray South caribou herd for decades, ever since he began to have memorable encounters with herd animals on hiking trips in the mountains near his home in Clearwater, B.C. He’s watched the herd disappear from the southern half its range and drop over a 20-year period from 350 animals to about 140 — even though, unlike other deep-snow caribou herds, the Wells Gray South population has about 40 per cent of its core range in a provincial park.

One problem, Goward observes, is that only about one-fifth of the Wells Gray South herd’s extended range occurs in the park, making animals vulnerable to human-induced predations arising from clearcut logging. The herd is also now forced to spend much of its time in steep, rugged terrain where hair lichens are less abundant, expending more energy to find food in deep snow than in preferred habitat further south. In winters where tree-dwelling hair lichens — their only source of food in the winter — are difficult to access, the herd must move to old-growth forests at lower elevations to find food. “This seasonal migration used to serve them well,” Goward says. “But now most of these old-growth forests have been logged.”

Goward was so disturbed by the downward population trend of the Wells Gray South herd that he launched a website called “Death by a Thousand ClearCuts: Canada’s Deep-Snow Mountain Caribou Going Down. “The pending extinction of the deep-snow mountain caribou is no oversight or accident,” the website says. “Rather, it’s a government-orchestrated instance of “designer extinction” — extinction by design — taking place in real time in one of the world’s largest, richest nations in utter contempt of Canada’s international obligations around species protection.”

The website details decades of resource decisions that have negatively impacted the Wells Gray South and other deep-snow caribou herds, including the Columbia North population. “The situation only keeps getting worse,” Goward observes. “Episodic winter starvation is just around the corner for many of the remaining herds.”

The Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship says it is committed to “helping caribou populations recover,” with province-wide investments of more than $10 million annually. “Caribou recovery is a complex, time-consuming challenge, requiring multiple approaches across the landscape to help stabilize and reverse the decline of caribou herds in B.C.,” the ministry says.

In 2022, the provincial government spent more than $1.1 million on habitat restoration work in southern mountain caribou ranges. Over the two previous years, it spent about $639,000, according to the ministry. That includes helping to fund a $300,000 Splatsin First Nation project to decommission two sections of road totalling about 10 kilometres. Calling habitat restoration an important, yet “band-aid” measure,” Bird says “it doesn’t replace what’s been lost.”

Ray lays some of the blame for the demise of Canada’s deep-snow caribou herds on piecemeal decision-making. “Each action, each development, is considered one one at a time. Not in a broader context,” she says. “And that’s how we’ve always done business. It’s the tyranny of small decisions. And so it just nibbles away, and there’s no overall responsibility and restraint at the appropriate scale.”

For Ray, there are only three choices for the Columbia North herd. One is to continue business as usual in the herd’s habitat. “Business as usual right now would be continuing under the mirage of meaningful long-term action, plus the continued resource development,” she says. A second scenario would be to control the pace and scale of development in the herd’s habitat while focusing on intensive management efforts, in the hopes that recovery might still be possible.

And the third scenario, she says, is “being truthful about what’s happening.”

The truth, Ray says, is that planning for industrial activities in the herd’s core habitat continues because governments have quietly deemed resource extraction in the region “more important than caribou.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

From disappearing ice roads to reappearing buffalo, our stories explained the wonder and challenges of...

Sitting at the crossroads of journalism and code, we’ve found our perfect match: someone who...

The Protecting Ontario by Unleashing Our Economy Act exempts industry from provincial regulations — putting...