Two blank cheques: are Ontario and B.C. copying the homework?

Governments of the two provinces have eerily similar plans to give themselves new powers to...

With the U.S. presidential election just weeks away, the fate of oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge — the largest intact wilderness in America — seems to rest in the hands of candidates Donald Trump (decidedly pro drilling) or Joe Biden (decidedly not).

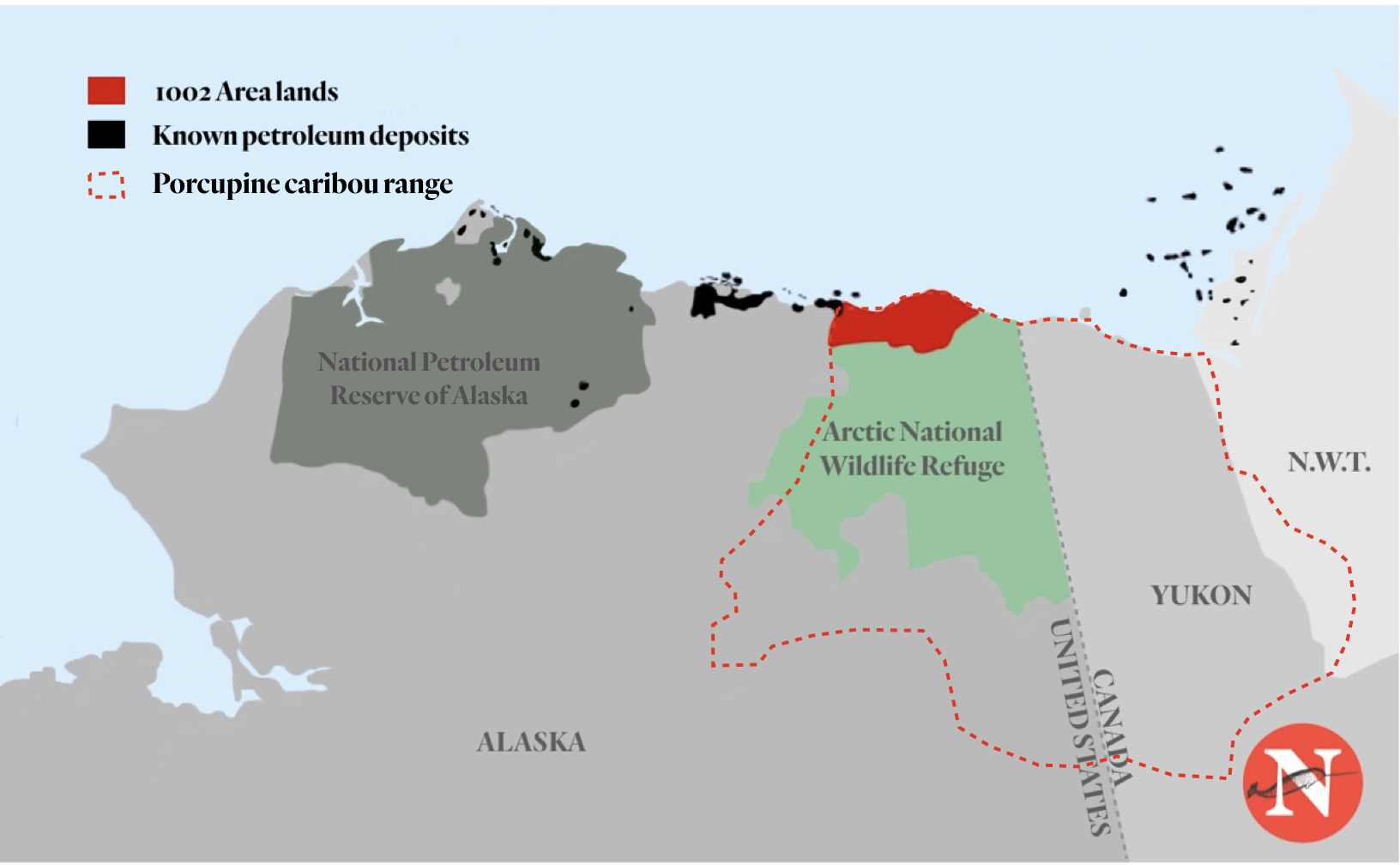

But whether or not industrial development goes ahead in a 1.6 million-acre parcel of the treasured Alaskan refuge, which provides important calving grounds for the threatened transboundary Porcupine caribou herd, could also come down to Canada.

Although in August the U.S. Department of the Interior gave the go ahead to the most aggressive lease program possible — which would open up the entire coastal plain of the refuge to potential drilling — here are all the ways Canadians could get in the way.

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is roughly 19.6 million acres (8 million hectares) of vast wilderness in northeastern Alaska that was set aside decades ago as a haven for wildlife and outdoor recreation. It’s home to a myriad of species including polar bears, migratory birds and the Porcupine caribou, a herd that undertakes one of the longest land mammal migrations on Earth.

There have been attempts in the past to get at oil reserves that lay beneath the refuge, including through exploration activities in the 1980s. But industry has been prevented from moving ahead with any major development, until now.

That’s thanks in part to a 2017 tax bill President Trump used to promote oil and gas activities and open up a portion of the refuge to potential drilling. The bill made way for at least two lease sales in the Arctic refuge by 2024, initiating an environmental assessment process that culminated in a record of decision that allows drilling in what is known as the 1002 area this past August.

Map showing overlap of 1002 area lands and the Porcupine caribou herd range. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Former vice-president Joe Biden has pledged to permanently protect the refuge as part of his campaign commitment to preserve the Arctic and tackle climate change.

In 1987, Canada and the U.S. signed a treaty to ensure the Porcupine caribou herd and its habitat is protected by minimizing possible long-term impacts while balancing subsistence harvesting.

That treaty has now become the focus of talks between the Yukon and federal governments, along with other interested parties such as Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation, the Gwich’in Tribal Council and the government of the Northwest Territories.

Pauline Frost, Yukon Minister of Environment, told The Narwhal the treaty may provide Canada with legal grounds to push back against the August decision.

“It fails to consider impacts to food security in the North,” Frost said. “It’s clearly for financial gains and quick access. It doesn’t consider long-term, specific impacts. It doesn’t correlate with how we do business in Yukon, how we do business in Canada, in terms of effective land management.”

Ian Waddell, a former NDP MP and B.C. MLA, told The Narwhal in 2018 that the treaty could be used to “raise a little hell” with U.S. counterparts. In an interview this week, he said this could take the form of diplomatic letters to the U.S. government.

“It gives us at least something to hang our hat on,” he said. “It’s not a big coat rack, but it’s something, and it can open up the dialogue.”

Jonathan Wilkinson, minister of Environment and Climate Change, said in a statement that the federal government has “significant concerns” with development in the Arctic refuge, noting bilateral agreements with the U.S. government are designed to not only protect the Porcupine caribou herd but also polar bears and migratory birds.

A spokesperson at Wilkinson’s office declined an interview.

The Yukon government has already proven it is willing to intervene in the issue. Last year it made a submission to the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, calling for a complete redo of what the territory considered spotty preliminary environmental assessment work.

Frost, who is Gwich’in from Old Crow, said the record of decision has impacted all Gwich’in nations, which are concerned about the caribou because they are so intricately connected to their culture.

“It affected me, it affected my whole community, it affected my family,” she said. “It’s certainly something, as a Gwich’in person, that I take to heart …”

Frost wouldn’t elaborate on the details of forthcoming talks between Yukon and the federal government, but said the record of decision and the treaty will be front and centre.

Members of the Porcupine caribou herd in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Photo: Matt Jacques / The Narwhal

Last week, the Royal Bank of Canada, the largest financial institution in the country, became the first Canadian bank to refuse to finance any oil and gas development in the Arctic refuge.

“Due to its particular ecological and social significance and vulnerability, RBC will not provide direct financing for any project or transaction that involves exploration or development in the ANWR,” reads RBC’s updated policy guidelines for sensitive sectors and activities posted on Friday.

A spokesperson told The Narwhal that the bank has never financed oil and gas development in the region and that the policy change was a “proactive” decision to ensure it stays that way.

A delegation made up of Gwich’in and members of the Yukon chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society have been putting pressure on not only RBC but other major banks such as TD Canada Trust, Scotiabank and the Royal Bank of Montreal since last December.

The move follows several U.S. banks, such as Goldman Sachs and Wells Fargo, which, earlier this year, publicly stated they would refuse to finance oil and gas development in the refuge.

Chris Rider, the executive director of the Yukon chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, said he hopes other banks in Canada follow RBC’s lead. If they do, that will help highlight the financial risk in store for companies bold enough to consider oil and gas development in the refuge. Severing the flow of cash earmarked for development in the area could thwart any attempt by companies to follow through with their plans, he added.

Dana Tizya-Tramm, Chief of Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation, said RBC’s commitment marks the first time a Canadian bank has taken meaningful strides to consult with affected First Nations and make a decision based on those deliberations.

“This is about leadership,” he told The Narwhal. “What we need more is courage, and we’re looking to the courage of financial institutions in Canada to stand in partnership with Indigenous people and stop ecocide.”

Several groups, including the Gwich’in Steering Committee, the Yukon chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society and the Alaska Wilderness League, are taking the Department of the Interior to court over its handling of the environmental assessment process.

The National Audubon Society and the Center for Biological Diversity, among other U.S. groups also launched a lawsuit against David Bernhardt, the secretary of the Department of Interior, who signed off on the record of decision.

Last month, attorney generals of 15 states sued the Trump administration’s move to open up part of the refuge to development, too.

Malkolm Boothroyd, campaigns coordinator with the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society Yukon, wrote in an opinion piece for The Narwhal that his organization’s lawsuit “challenges the legality of Interior’s environmental review,” stating “the environmental review gave little heed to the seven original purposes of the Arctic refuge, like protecting wildlife, wilderness and subsistence.”

His group, along with 12 others, allege that the Department of the Interior “broke the law by disregarding the refuge’s original purposes and failing to safeguard those purposes through the design of its oil and gas leasing program.”

Adam Kolton, the executive director of the Alaska Wilderness League, said that if Trump is re-elected, litigation will continue, noting there are currently four lawsuits in motion that challenge the record of decision, including one brought by Earthjustice and the Natural Resources Defense Council.

“If Trump wins, these are still going to be active lawsuits, and, depending on the outcome of that litigation, the administration could be forced to redo its work, and this could substantially delay plans to offer the area to lease,” he said. “We think the administration really sidelined scientists, sidestepped environmental laws and went about this in a really reckless fashion.”

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Photo: Matt Jacques / The Narwhal

If the Democratic party wins the U.S. election, the battle to keep oil drilling out of the refuge might all but evaporate.

Biden has pledged to permanently protect the Arctic refuge, calling Trump’s move to open oil and gas development there and in other areas an “attack on federal lands and waters.”

He has several campaign commitments that involve greater protection for the Arctic, including a moratorium on offshore drilling in the Arctic Ocean and prioritizing climate change at the Arctic Council, an intergovernmental body that seeks to address problems faced by people who live in the area.

Tizya-Tramm said that Biden’s campaign suggests that advocacy efforts in both Canada and the U.S. are working.

“We’re almost there,” he said, adding that leaders near and far can take a page from Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation, which is proving to the world that sustainability is possible.

“In our community, as we advocate for the protection of the caribou, we are charting the path in North America as Indigenous people to what renewable economies look like, to what a renewable, permanent presence on the land looks like, and there is no reason why the U.S. government cannot enjoy the same successes that a small village of 250 people north of the Arctic Circle are levying today,” he said.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Governments of the two provinces have eerily similar plans to give themselves new powers to...

Katzie First Nation wants BC Hydro to let more water into the Fraser region's Alouette...

Premier David Eby says new legislation won’t degrade environmental protections or Indigenous Rights. Critics warn...