A light snow started to fall as leaders of the Dehcho First Nations, federal officials and Environment and Climate Change Minister Catherine McKenna gathered in Fort Providence, Northwest Territories, Thursday for an announcement that has been more than 20 years in the making.

“It was a beautiful day. You could feel that the room was full of pride and hope,” said Dahti Tsetso, Dehcho resource manager, who heads the Indigenous guardians tasked with protecting the newly announced Edéhzhíe (eh-day-shae) Indigenous Protected Area.

The snow gave a special atmosphere to the traditional fire feeding ceremony when tobacco and special foods are put in a basket to honour ancestors and the spirit of the land and water, she said.

“Then to drum music and drum prayers the offerings are fed into the fire. It was a beautiful way to start such an important event,” Tsetso told The Narwhal.

Grand Chief Gladys Norwegian said people in the communities of Fort Providence, Jean Marie River, Fort Simpson and Wrigley have worked hard for decades to protect the massive culturally and ecologically significant area.

“It has been a long time coming, but I was always hopeful,” Norwegian said.

Edéhzhíe Indigenous Protected Area. Illustration: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

In addition to rich wildlife and myriad berries and medicine plants the area has a wealth of spiritual connections and many Dene myths are based in the Edéhzhíe.

“For some of our leaders this was a very emotional day. The Dene have a special relationship with the land…It is a place our ancestors used from time immemorial,” said Norwegian, who hopes the Edéhzhíe will be an example of how government and Indigenous communities can work together.

The 14,281 square-kilometre Edéhzhíe protected area is the first of what Minister McKenna promised will be many new Indigenous Protected Areas funded by the federal government’s nature legacy and the addition will make a dent in Canada’s international commitment to protect 17 per cent of land and fresh water by 2020.

“By creating the Edéhzhíe Protected Area and National Wildlife Area under the leadership of the Dehcho First Nations, we are protecting a very special place in Canada while working in partnership with Indigenous Peoples to advance reconciliation,” McKenna said in a news release.

The new classification of Indigenous Protected Area will offer the same protection as a National Wildlife Area.

Valérie Courtois, director of the Indigenous Leadership Initiative, told The Narwhal the establishment of the new protected area is an important step ahead for Indigenous-led conservation.

“The kind of past models of protected areas has always been led by crown and public governments and this is a case where the Dehcho under their own authority and own laws were able to declare the Edéhzhíe as a Dehcho protected area,” Courtois said.

Tania Larsson stands watch on the shore of Great Slave Lake. She’s a member of Dene Nahjo, an organization of young leaders looking to advance social and environmental rights for indigenous people in the N.W.T. Their motto is “Land, Language and Culture Forever.” Photo: Pat Kane

“And to the credit of the federal government they responded to that and recognized the role of Indigenous governments as decision-makers over their own lands.’

The Edéhzhíe, in the southwestern Northwest Territories, will be managed through a consensus-based management board, with federal and Indigenous members, with eyes on the ground provided by the Dehcho First Nations Indigenous guardians.

“Any protected area really only becomes real when there are people working in it,” Courtois said. “We protect areas from humans, that’s the idea of protected areas. We need that presence and focus and relationship there to make sure the reason we’re protecting these areas is fulfilled.”

The emergence of Indigenous guardianship over protected areas is charting a new path forward for conservation, she added.

“There always is a risk of conservation being a new tool of colonialism. Certainly in designation of lands — whether for development or conservation — this can be a tool of colonial governance.”

“That’s so 1990s,” she said. “Today it’s really about strengthening and holding up Indigenous leadership. In order for us to be who we are on our lands, it requires healthy lands.”

Residents from Fort Good Hope check beaver traps. The area is rich in shale and potential natural gas deposits: a traditional hunting territory that outside exploration companies are interested in. Photo: Pat Kane

Residents of Behchoko, N.W.T., make their way to Whitebeach Point, an area where mining companies want to develop silica for use in fracking. Photo: Pat Kane

In addition to monitoring, Tsetso explained, the guardians will also work on mentoring youth and the program has grown from a few people doing aquatic monitoring to a full-fledged program.

“Since 2016, with the support of member communities, we have put a lot of focus on growing the program and this past year we have entered into agreements that have allowed us to add 12 guardians,” she said.

“They will focus on research and monitoring and support of on-the-land programming for youth,” Tsetso said.

Dahti Tsetso, resource manager for the Dehcho First Nations, will lead the Indigenous guardians tasked with monitoring the protected area. Photo: Amos Scott

The relationship between the government and area First Nations has not always been so cordial as the Dehcho First Nations struggled to protect the mineral-rich Horn Plateau — an integral part of the new protected area — from resource development, which involved a 2010 court case against the Harper government after it dropped protections against mining.

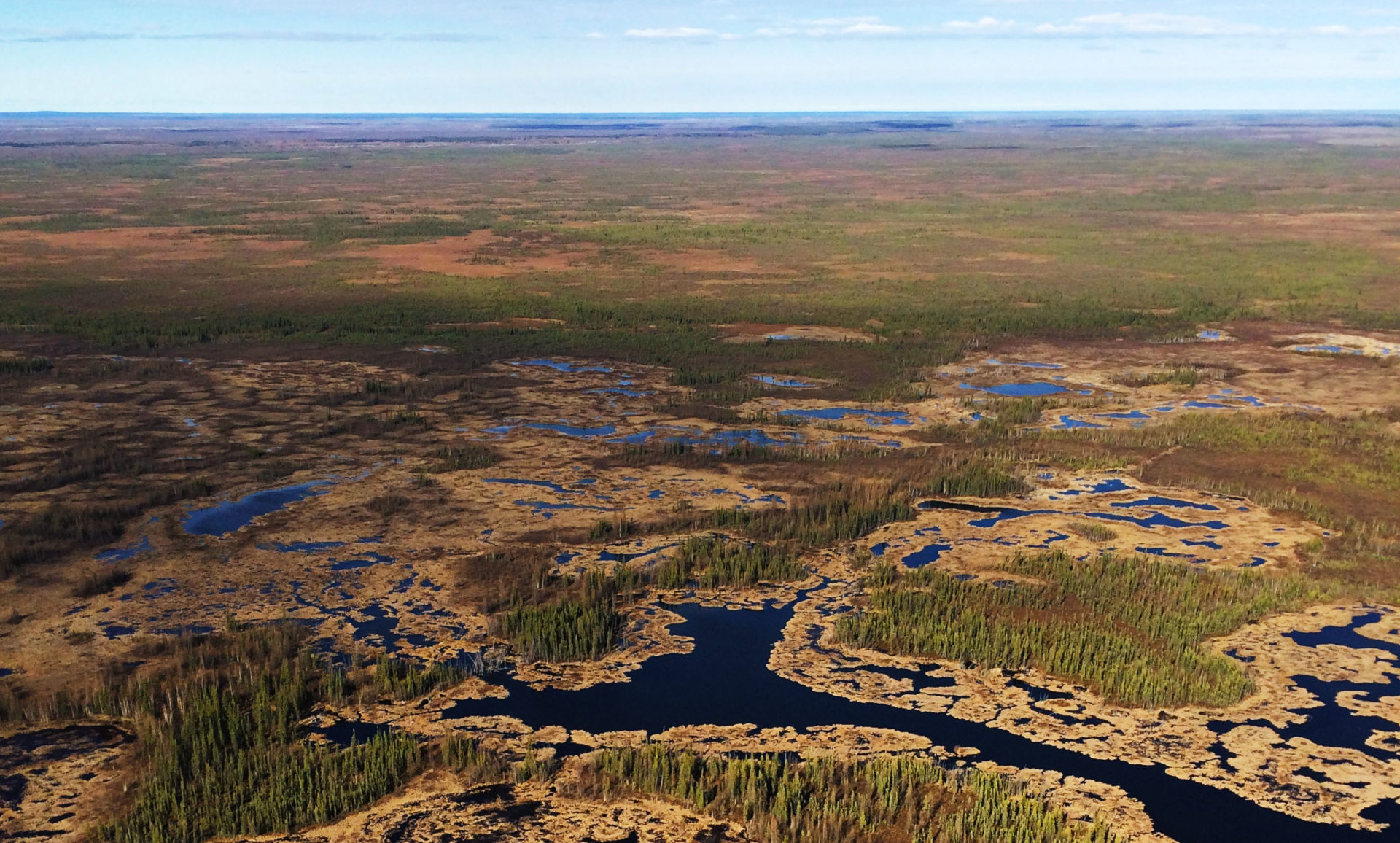

Now, all industrial development will be banned and the Dehcho K’ehodi Indigenous Guardians and the Canadian Wildlife Service will draw on Dene culture and western science to protect the vast region of boreal forest, lakes and wetlands.

The vast wilderness area is home to species at risk such as the boreal caribou and wood bison.

It is expected that Edéhzhíe will be particularly significant for boreal caribou herds as climate change affects their southern ranges.

The Edéhzhíe Indigenous Protected Area is home to rich river systems and waterfalls. Photo: Environment and Climate Change Canada

Edéhzhíe also supports 36 types of mammals, 24 species of fish and 197 bird species, including at risk bird populations such as the rusty blackbird and short-eared owl.

“It’s incredibly abundant in fish and wildlife and, in the past, elders have often referred to Edéhzhíe as being the breadbasket of the Dehcho because in times of scarcity they could always go up to Edéhzhíe and find refuge in that area and be able to harvest fish and wildlife,” Tsetso said.

Many members of the communities continue to use the area for hunting and trapping and most people in the area supplement their diet with country food, she said.