The Right Honourable Mary Simon aims to be an Arctic fox

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

Back in February, Canada was in the midst of a different reporting storm about state power and violence against Indigenous People than the one we’re in now.

The RCMP had arrived on the territory of the Wet’suwet’en to enforce an injunction against opponents of the Coastal GasLink pipeline. The story catapulted the Canadian media into a paroxysm of coverage that gave rise to a rigorous debate about how to refer to the individuals the police had been dispatched to arrest: protesters or land defenders?

The conversations swirling around in newsrooms (including our own) at the time were about language, yes, but were in a much deeper way hitting up against an exposed nerve of Canadian history. The Wet’suwet’en had never ceded their territory to any colonial government.

Could these Wet’suwet’en members, Hereditary Chiefs and matriarchs who refused to allow an unwanted project on their own land be rightfully, fairly designated protesters?

“I got interviewed by a number of mainstream media organizations and some smaller organizations as well which were really trying to think about how we consider these terms,” said Candis Callison, Tahltan member and University of British Columbia associate professor of journalism.

“My answer as a kind of expert voice was to say, ‘Well, land defender is an absolutely appropriate term because it points to the long relationship that Indigenous People have with their land.’ ”

That moment stands out in Callison’s mind as an example of the critical role journalists play in contouring public narratives and, beyond that, influencing the way Indigenous lives and interests are represented or, more often, misrepresented in media coverage.

The term protesters casts a delegitimizing light on the Wet’suwet’en in their standoff with the police. But to use the term land defender draws in a whole history and way of being that points to Indigenous Peoples’ particular relationship with the land.

“I think that’s still a relatively new concept,” Callison said. “Especially here in British Columbia, there has been so much talk and coverage of land claims and land rights and at the same time I think the general public has a hard time understanding what that means and what that’s about.”

For Callison, the move from conceiving of the Wet’suwet’en as protesters to land defenders holds the opportunity for a fundamental shift in thought.

“So journalists moving to new understandings of Indigenous People as in a relationship with lands, with waters, with nonhumans, as thinking about nonhumans as a part of their communities and as relatives — that is a major shift that might provide an added dimension to thinking about political structures and the ways in which things need to change in relation to Indigenous People and access to justice.”

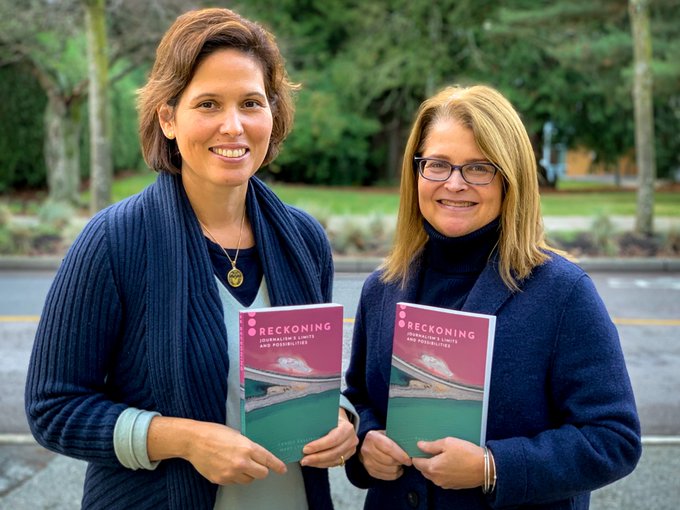

Callison, along with co-author and fellow UBC associate journalism professor Mary Lynn Young, contends with the role of journalism in shaping broader narratives about race, culture and reality in their recent book Reckoning: Journalism’s Limits and Possibilities.

As scandal, uprising and high-profile firings rock the journalism industry across North America in the midst of ongoing demonstrations to protests police violence against Black and Indigenous People, we spoke with Callison, who is a member of The Narwhal’s board, about what this moment’s reckoning should mean for journalism in Canada.

Authors of Reckoning: Journalism’s Limits and Possibilities, Candis Callison, left, and Mary Lynn Young, right. Photo: UBC Journalism / Twitter

One of the arguments we make in the book is about how journalism, despite its claims to objectivity and being outside both culture and the social mores of its time, actually participates in propping up social order and preserving the status quo. The story journalism tells itself is that it has fought for justice.

In some cases that is true — journalism has done great work and good interventions. But oftentimes journalism also is basically amplifying dominant narratives and dominant voices. I think this moment is really interesting because there are so many digital platforms that are not only holding media accountable for the kinds of narratives and the language that is being used and the kinds of voices that are being amplified but also highlighting the gaps in media not only in terms of who is in the newsroom but in terms of what kinds of stories are being told and basically how the present moment is being narrated.

Part of the argument we make in the book is that journalists need to think beyond just reporting on events as one-offs and think about how histories and structured systems are a part of what events can reveal. Events are often intersections of many things colliding.

Instead of thinking of this moment as one of disorder, we need to think about how it reveals the social orders that have preserved and kept injustice in place, that have propped up systems that have systematically dispossessed, disenfranchised and excluded some communities.

I think the challenge in thinking about social order is it’s kind of a nebulous thing, but once you really recognize it, you recognize the way in which media have tended toward certain kinds of voices, certain kinds representations and have created a sedimentation as a result in which even new journalism has to contend with the way Indigenous communities have been represented, the way Black communities have been represented.

This is a moment of reckoning because of that sedimentation being present, because there are so few Black and Indigenous and People of Colour in the newsroom.

Objectivity in journalism really comes out of a moment in time for the profession when it was trying to gain legitimacy. Historians generally look at the period of the 1920 as the time when objectivity emerged as a professional good, a professional norm.

We’re 100 years past that point and there have been enormous changes in the way society operates and our cultural points of view — our sense of what’s ethical, what’s good and what’s right has also changed, to a certain extent.

Journalism really borrowed from science back in the 1920 in adopting this “view from nowhere.” [While] science has been critiqued by feminist and postcolonial scholars, by Indigenous scholars who thought closely about the way that science and colonialism have walked hand in hand … journalism hasn’t kept track. It’s only been over the last 20 years that we’ve seen some of that move into critiques in journalism.

I think to me the work for individual journalists is to locate themselves within a profession that has problematically supported a status quo, supported colonialism with or without realizing it. And to recognize their own personal histories are also relevant. The kinds of questions that individual journalists think are important, that editors think are important, are informed by media practice, existing media narratives, but also their knowledge, how they come to know what they know.

One of the core questions of the book is, how do journalists know what they know? How do we decide what’s good journalism? And who gets to decide?

The kind of inherent power relations in narrating what our present is, and deciding what’s relevant, who the relevant and expert voices are and what is considered news are all questions journalists aren’t thinking about when they’re out there reporting the news.

I think this is the real challenge: journalism has very much been event focused and has not thought about the larger narratives that it’s participating in, that it’s continuing to repeat and the ways in which broader questions — that challenge the status quo and serve very diverse audiences — need to be asked.

In the book we draw from feminist and Indigenous scholars who have actually thought about how important it is for certainly scientists, but we apply this to journalists, to consider themselves on the same plane as the people they’re reporting on, investigating and trying to understand.

So locating yourself in your own social history and social situation becomes really important for understanding the people you’re reporting on. I would argue based on that scholarship that you have actually a stronger objectivity if you are considering yourself as well.

There are good and better and best ways of checking your facts, of making sure you have well-supported perspectives and narratives on events that occurred. But as a journalist you are always going to be contending with multiple perspectives and multiple truths of what really went on in a situation. In situations of conflict that becomes an even greater challenge.

So recognizing that you are coming from somewhere

becomes essential to becoming aware of what kinds of questions you should be asking, what kinds of questions you think are important, who are the experts that can help you shed light on a situation, whose voices need to be heard more than others.

When I started researching climate change, it was in the early 2000s, and one of the things that piqued my interests was that so much of the blame at the time for the public not caring, not being engaged with and not even knowing about climate change was put at the feet of media. My contention at the time was, ‘Hey, you’re putting way too much at the feet of journalists — they can inform you about an issue, but they can’t make you care about it.’

That was me starting to think about climate change and media.

As I got deeper I started encountering these interesting social movements. I came across the Inuit Circumpolar Council and at that time Sheila Watt-Cloutier was bringing a human rights case (to seek relief from the impacts of climate change on the Inuit) before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Then I encountered American evangelicals who were trying to get 30 million American evangelicals engaged in climate change especially when it had been so associated with a left-leaning political stance and evangelicals were associated with a right-leaning political stance.

The other group was the corporate social responsibility group. They were thinking about how Wall Street could become engaged with climate change and they turned [climate change] into climate risk to really think about it.

These different ways of coming at climate change helped me start to realize that there were different ways of talking about it, there were different languages and vernaculars and a different way of making sense of the world that is behind how you talk about climate change.

This is how I began to think about the subtitle of the book: The communal life of facts. Facts have a social life. They get taken up in different ways, they enter into language in different ways, they get put into other moral and ethical codes, such that they come to have meaning, such that people have a rational to act on an issue.

To me there’s only so much work that journalism can do around issues like this that do have to be taken up by social groups. Climate change has to be invested with meaning, ethics and morality in order for people to come to be engaged with it as an issue and to make changes in their personal life and push for political changes.

In the 20 years almost that has elapsed, you see how some of what I thought back then has been borne out: you see young people taking climate change up, talking about it in their own terms and making it meaningful.

This still speaks to the prominent role that journalism can play, but there are also many different social influences and affiliations that inform how people think about the facts and information that they get from news sources, from works of journalism.

I think a lot about crisis, both because of the climate crisis and also because of the way that journalism has described itself as being in crisis especially because of economics and technological change. We have seen enormous changes in journalism.

The last 20 years that I’ve been working in or studying journalism, you see how vast the changes are and the kinds of news sources and opportunities for experimentation and opportunity for an organization like The Narwhal to emerge. This is an incredibly rich time. At the same time we’re seeing the demise of longstanding news organizations at the regional and national level, we are seeing a decline in the size of newsrooms and the reach of big media.

So scholars, industry people, everyone is talking about this as a crisis. In the book we are thinking about this as a much more profound crisis, because if you take into account also the way scholars, Indigenous and Black and other communities of colour have critiqued and been misrepresented or not represented … you really see there is a need for a much more profound change.

I think some of the newer media represents an emergence of what we call “multiple journalisms.” There are multiple ways of doing journalism right now and multiple ways of getting journalism funded and that is a real challenge and at the same time a real opportunity because you are seeing publications like The Narwhal and these new experimental relationships with audiences and thinking about who audiences are.

This is a really interesting moment where especially in the last week and a half where you see journalists having conversations that … I couldn’t have anticipated even five years ago, like these open conversations about who is in the newsroom, about what journalism is doing and what it thinks it’s doing and who it is accountable to. And also the question of how we reckon with the past, of sedimentation, representation and narratives that haven’t served publics that now have a strong voice on Facebook and Twitter and other platforms.

In the book we quote my fellow Narwhal board member Tanya Talaga as saying before Idle No More and before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, there wasn’t a lot of fair and non-racist reporting on Indigenous communities. And I think that’s a fair summary comment on the state of media.

I think there is still a fairly profound and ongoing reckoning. I think you see that for example in events like the Wet’suwet’en land defense that recently happened.

I have such deep respect for the Wet’suwet’en People not only because they brought one of the most important cases to the Supreme Court — Delgamuukw — but because when it came down to Unist’ot’en, the people who were there hung red dresses, they connected Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls to what was happening to our lands, to resource companies coming into their lands. The state of Indigenous People is connected to the long history of colonialism and to the way the state has imposed certain structures and made access to justice very difficult for many Indigenous People.

Red dresses hung at the Unist’ot’en Healing centre as police prepared to make arrests while enforcing a Coastal GasLink injunction in February 2020. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

I think this is the challenge for journalists who maybe aren’t aware of that history and maybe aren’t aware of how deeply impacted Indigenous People are by various aspects of colonialism.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission was such a major contribution to a mainstream society thinking about what happened to so many generations of Indigenous People and how important it was for survivors and those of us who have been affected by intergenerational trauma to speak and to be heard. At the same time this was already a history that Indigenous People knew intimately. We didn’t have to be told because so many of us — myself included — had parents who went to residential school. This wasn’t new history for us.

But having it integrated it into Canadian awareness and consciousness of history, this question of “what is our shared history” really came to the fore in the reporting and the report that came out of the commission.

I think there is still a lot of work to do to think about what that means in everything from decision-making about resource development to how we set up health systems to how we respond to COVID.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...