Ontario’s public service heads back to the office, meaning more traffic and emissions

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

This story is a collaboration with The Sprawl, an independent news outlet based in Calgary. Jeremy Klaszus contributed reporting and research for this story. You can listen to the first part of the podcast on the Three Sisters saga, where he goes deep into issues including the old mine works, by playing the embedded audio below, or read the transcript here.

Raymond Haimila can still remember a time when lots in Canmore sold for $50 and coal dust ran through the veins of the locals. It’s a far cry from the million-dollar homes and weekend traffic that now characterizes this Alberta town on the outskirts of Banff National Park.

Haimila worked the coal mines that built the town. His father worked them too, a lot of people did. Until they didn’t.

“When the mine shut down, so many people thought there was no future here, and a lot of them left,” Haimila says, driving through the area in his Volvo.

But the town didn’t die. The million-dollar homes attest to that. They also attest to the fact that a lot has changed in the wide Bow Valley on the eastern slopes of the Rockies, just 100 kilometres from Calgary, the corporate home of the oilpatch.

Now the area is poised for even greater change.

Late last year, Canmore town council was forced to approve two plans that make up the Three Sisters development — a sprawling project that would take up almost all of its remaining developable land, nearly double the population and eat into critical wildlife habitat.

Councillors vehemently opposed to the development had no choice but to cast their votes in favour after the town lost its last legal battle against it. Several of their colleagues had to recuse themselves from the decision due to a $161-million lawsuit filed by the developer.

It was a tearful and acrimonious end to years of resistance and stood in stark contrast to council’s rejection of the development in 2021 following an outpouring of public opposition.

But it was a sigh of relief for Three Sisters Mountain Village properties, which owns the land. The company argues it will bring much-needed housing to the valley, and safe passage for wildlife through its provincially approved corridors

The path to that tearful meeting is long and winding.

It has been more than 30 years since a provincial tribunal first approved a resort project on those lands, but the saga and the complex issues facing the development and the town go back even further — to the Winter Olympics in Calgary, to those coal mines and even further back to a time when wildlife roamed free in the valley bottom.

The Narwhal, in collaboration with The Sprawl, spent months combing through stacks of documents, collected over the years through freedom of information requests filed by the late David Owen — a Canmore resident long opposed to the project — as well as pouring over archives, legal documents and interviewing more than two dozen sources.

The story that emerged is one of money and politics, of nature and recreation and the inevitable clash that comes when those values collide.

It is a convergence of forces in a place that has served as a place of convergence long before the settlers arrived.

“Our creation story begins in these mountains. We have many sacred sites, places of worship and areas of harvesting, reflection, meditation and fasting in the sacred mountains,” John Snow Jr., with the Stoney Nakoda Nations, said during those public hearings at Canmore town council in 2021.

“These mountains are sacred places.”

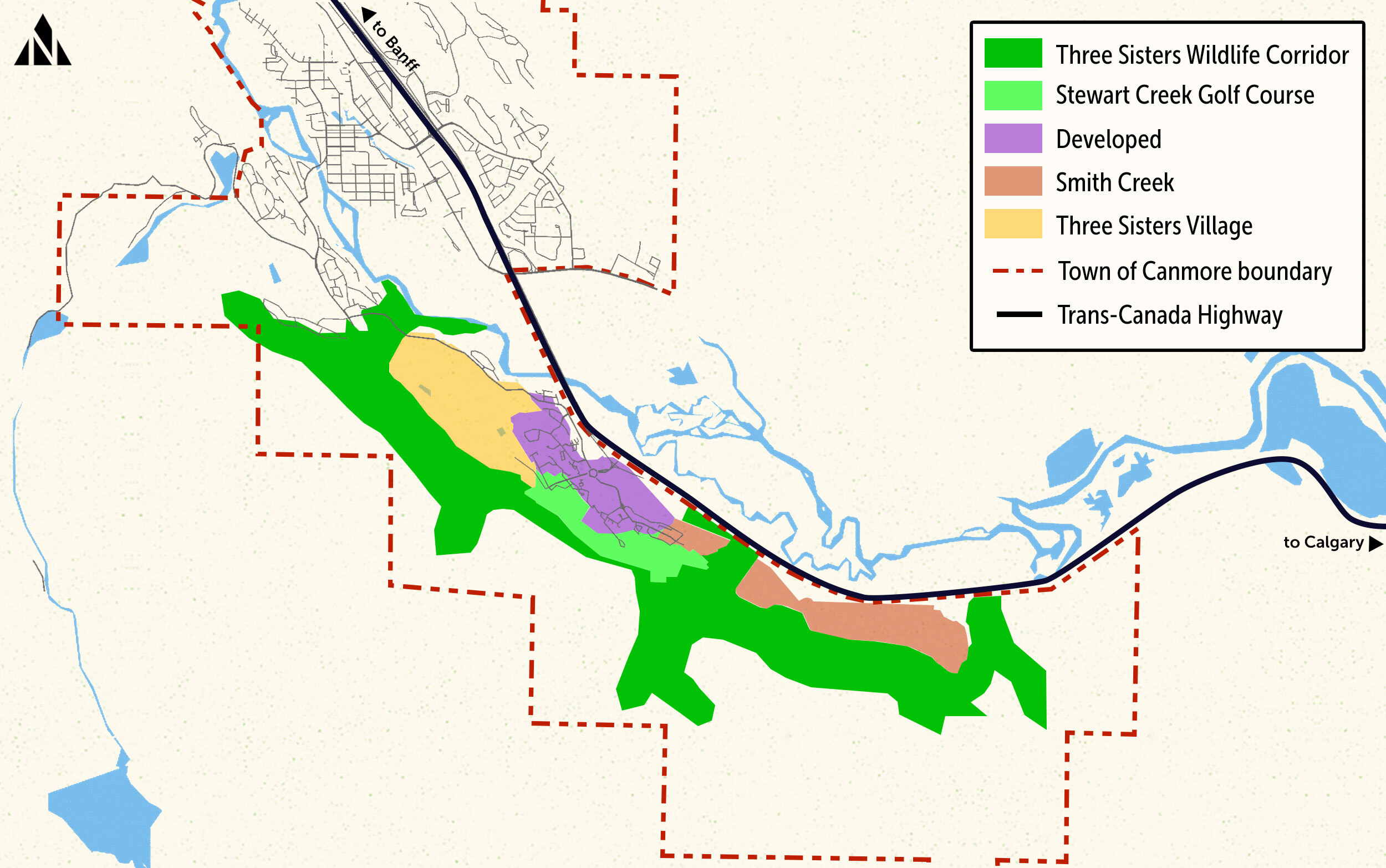

The plans approved by council late last year are known as the Smith Creek and Three Sisters Village areas structure plans, covering large sections of land owned by Three Sisters Mountain Village Properties that stretch down the Bow Valley south from downtown Canmore.

Smith Creek is largely residential, while the village is a sort of secondary downtown geared more towards tourism. Together, they will swell the population by up to 15,000 people, depending on the season or day of the week, and extend Canmore far to the south, across the Trans-Canada Highway from Dead Man’s Flats.

Canmore’s current population hovers around 14,000.

“I would say that this is the most complex project of its kind in Alberta, for sure. And probably, arguably, throughout much of Canada,” Chris Ollenberger, the director of strategy and development for Three Sisters, says in an interview. “It’s got a lot of layers to it.”

That complexity has posed significant challenges for the company and its predecessors, but the location is irresistible, so close to Calgary and its international airport. So close to Banff and ski hills, the nordic centre and world-class hiking.

“There are very few opportunities like this, I would even argue North America-wide, which … has all of these things coming together,” Ollenberger says.

It attracts Calgarians who can commute to work in the city, and it attracts international buyers who can easily fly in, rent a car and quickly find themselves in the Rockies.

It’s why a rotating cast of developers have held on to the dream of building on this long stretch of land, even as obstacles piled up and money evaporated.

But the value of the land isn’t just financial. It’s also why the town has fought to its last legal breath against a development it sees as too big and too destructive, and why many in Canmore still vow to resist it.

The valley was not just home to First Nations before the settlers poured in. Animals have used the Bow Valley as a place of transit and foraging for millenia. Carpeted thick with pines from the treeline down to the electric blue, glacier-fed Bow River, the area is important for its scale and its bounty.

Large mammals, particularly grizzly bears, favoured the low flat ground along the river that’s now favoured by humans and their homes.

Elk, deer, sheep, grizzlies and more still use the valley to roam from east to west and to wander from the protected enclave of the national park and south into the mixed-use area of Kananaskis Country.

When the settlers did come, the mountains that remain sacred to the Stoney Nakoda inspired another sort of awe.

Trains were built and visitors flocked to nearby Banff — Canada’s first national park — with its castle-like hotel erected by the same company that laid the rails.

But that awe was limited in the settler imagination. It wasn’t sacred so much as sold.

Despite its proximity to Banff and the soaring cliffs that surround the town, Canmore wasn’t part of the brochures. The town was established by the Canadian Pacific Railway as a pit stop to fix up, store and refuel its trains. Rich coal seams helped power the locomotives and the industry kept the town alive for almost a century — first feeding the trains and then Japanese steel plants.

“People didn’t like to stop in Canmore” Haimila says. “They felt nervous here. They would rather just go straight to Banff because mining towns had a bad reputation, I guess.”

The fortunes of the mines ebbed and flowed over the decades — through wars and the depression, through changing demand and fickle markets — but the tunnels continued to expand, the earth under Canmore hollowed. The town remained fixed on its one major industry.

By the ’70s, however, Canmore was struggling.

The mines were sold to a Hawaii-based conglomerate called Dillingham Corporation, but it would never recover. Dillingham closed the Canmore mines in the summer of 1979, on a day that became known locally as Black Friday.

A lot of people left and the future, briefly, looked bleak.

But others had different ideas for this valley oasis, and pressure was already starting to mount.

There is an expansive feel to the mountains and the valley in this little pocket of this corner of the world. Often a surreal blue sky arcs overhead, punctuated by the sharp stabs of prominent peaks. There is a sense of enormity.

The more poetic can attribute all sorts of personalities and pursuits to it — adventure, vision, hubris or even quiet contemplation.

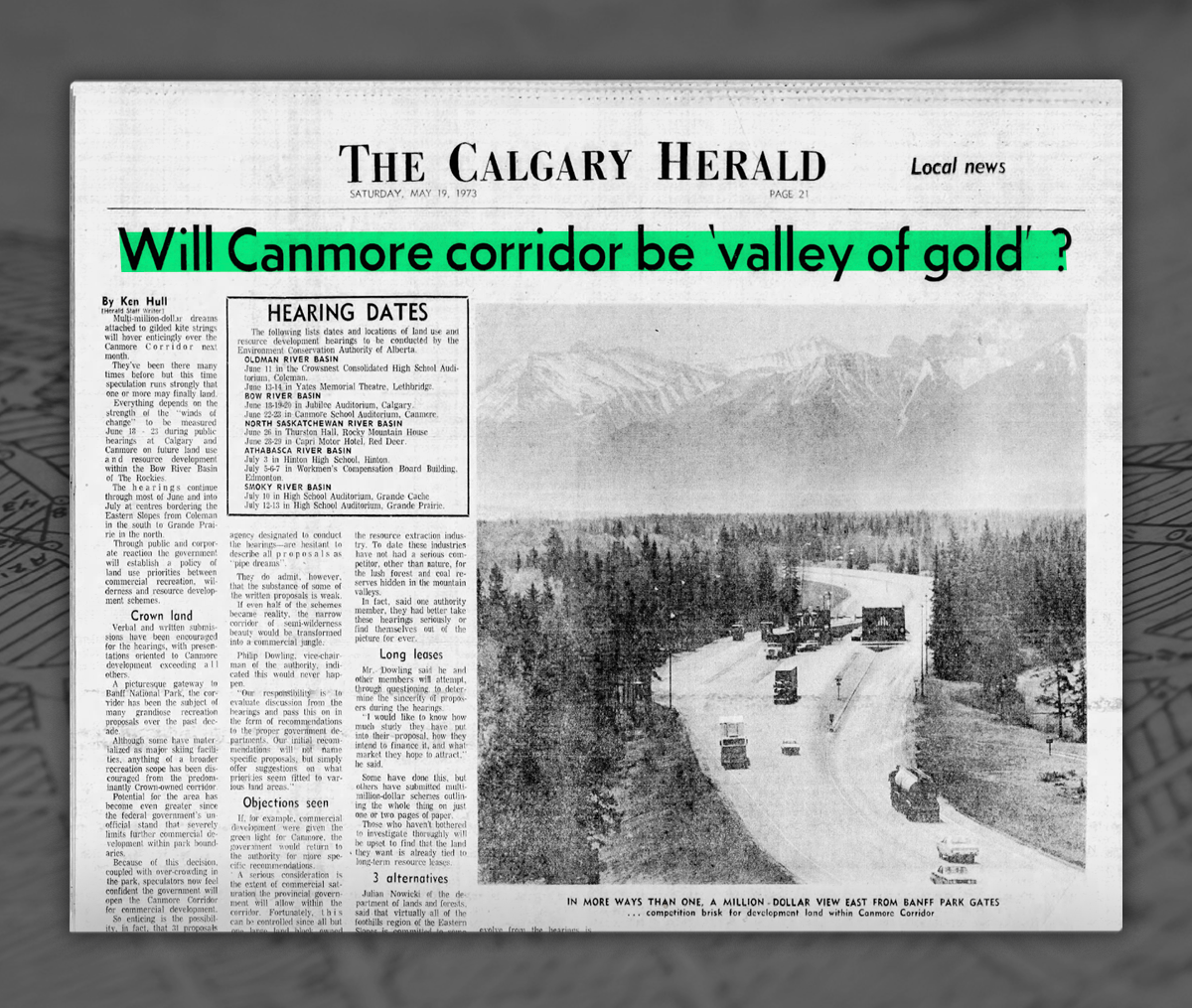

Even before the mine closed, the provincial government was thinking about change and held public hearings in 1973 into the future of what was called the Canmore Corridor.

According to reports from the Calgary Herald at the time, the hearings attracted 31 proposals “by individuals and groups eager to cash in on what might become Alberta’s Golden Valley.”

“If even half of the schemes become reality,” it noted, “the narrow corridor of semi-wilderness would be transformed into a commercial jungle.”

But the long spit of land that extended down the valley from the town wasn’t open for that kind of business. The mines still operated, for one, and what wasn’t owned by Dillingham was held by the Crown.

Dillingham wasn’t against a shift, but change would come slow. The company told the hearings it might consider building a golf course, around 3,000 housing units and even an artificial lake — in 50 years or so.

That change, if it came, would fit into a larger pattern. The town built by coal was surrounded by land meant more for recreation than toil, with Bow Valley Provincial Park (incorporated into the larger Kananaskis Country in 1978) and Banff along its various edges.

But in 1981, a delegation of Albertans got the news they’d been waiting for, and working on.

“After 30 years, at last we’ve got it,” Frank King, the CEO of the Calgary Olympic Committee, said after hearing the city would host the 1988 Winter Olympics. “Hallelujah! It’s going to change the future of Calgary. Calgary will become, now, an international city.”

The Games were a sort of coming out party for Calgary, a once-small outpost on the western frontier that had reinvented itself with the help of vast oil reserves.

The eyes of the world didn’t just focus on Calgary, where many of the facilities were built and the ceremonies held. A new nordic centre was built in Canmore and the nearby Nakiska ski hill opened in Kananaskis to host events.

“That was big time. That was huge. That really started the property values going up,” Haimila says of the time.

“People from all over the world started to buy properties here.”

Even before the international camera crews arrived and expanded the settler awe farther afield from Banff, money was changing hands.

In 1980, Peter Pocklington, then the owner of the Edmonton Oilers and now infamous for trading Wayne Gretzky, bought the land from Dillingham — just as Gretzky completed his rookie season.

Pocklington’s company, Patrician Land Corporation, had made the purchase specifically for a future residential development, but the project soon went bankrupt — a precursor of challenges to come.

It wasn’t until after the Olympics, in 1989, that the land was purchased by “a group of powerful and politically well-connected Calgary businesspeople,” as the Herald put it. John McInnis, an NDP MLA at the time, decried them as “cronies” of Alberta’s conservative government.

One of those new owners was King, who had just overseen the wildly successful Games. He was joined by Bill Dickie, Alberta’s mining minister in the ’70s and Richard Melchin, who’d previously been president of Pocklington’s Patrician Land Corporation — a precursor, this time, of familiar faces showing up even as ownership of the land changed.

The new company was called Three Sisters Golf Resorts, and they were talking about a big project with hotels and housing for some 11,000 people — and maybe even an amusement park.

“Certainly in the late ’80s, early ’90s, there was almost the sense of being under siege,” Ron Casey, who has been a Canmore councillor, the town’s mayor and a former provincial MLA, says. For a time, Casey was also an employee of Three Sisters, hired to improve relations with residents and the town, and to try and work through issues collaboratively.

That siege wasn’t just coming from those well-connected owners.

In 1991, the town annexed the Three Sisters lands from the Municipal District of Bighorn and inherited the Three Sisters proposal. In the same year it annexed the land, it released a tourism investment plan for the valley that pledged millions of dollars to help move the Three Sisters project and the Silver Tip development across the valley forward.

The plan estimated the town, at that time, would face $115 million in infrastructure costs (in 1991 dollars) and asked for the province to pay up to $77 million of it.

The developers also negotiated a land exchange with the province, a process of swapping dozens of parcels of privately owned land for Crown land. Another swap would follow in 1994 to ensure the owners didn’t lose out when environmentally fragile areas were barred from development.

In total, 751 hectares of environmentally sensitive land was traded to the province in exchange for 619 hectares of “titled, optioned and leased lands” for development by Three Sisters between 1990 and 1994, according to those agreements, part of the stack of documents obtained by Owen.

Not everyone was against development, but the population had doubled since the mine closed and the land was increasingly valuable. Casey also says the money and the connections of the new owners made people in town feel overwhelmed.

“You had people coming in that had way more capacity than anyone locally had ever dreamt would show up on our doorstep,” he says. “And there was a bit of a concern in the community that we were being outweighed.”

That sense of a power imbalance only increased, and lingers still, when another provincial intervention sealed the town’s fate.

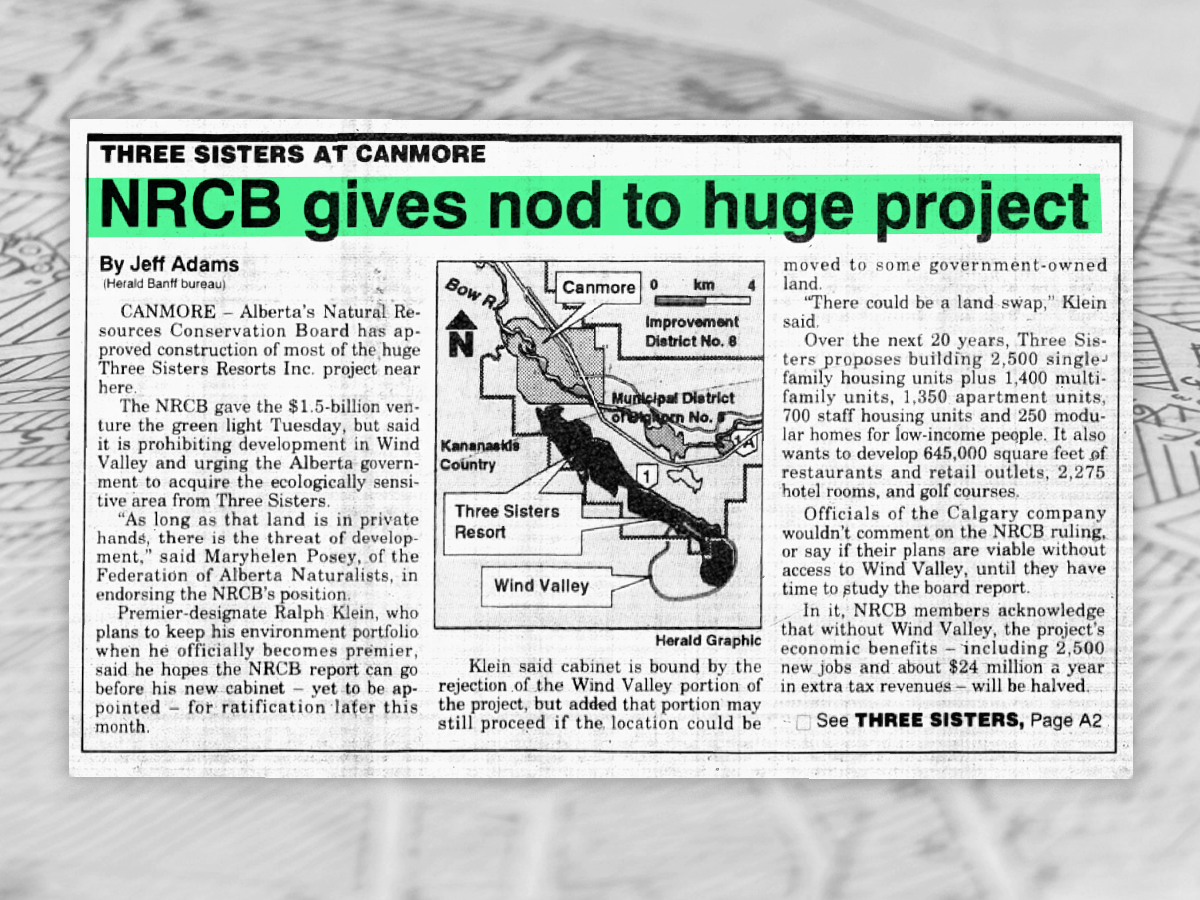

The scope of the development proposed for the Three Sisters land — and its focus on tourism — was so significant that it qualified for review by the Natural Resource Conservation Board, a quasi-judicial provincial body that examines large projects to determine whether they’re in the public interest.

A purely residential development would never fall under its purview.

It approved the plan, with conditions, in November of 1992 after hearing from 41 organizations and individuals in person and more through letters, citing a public interest despite the impacts on the environment.

But it did prevent the owners from developing a resort in the sensitive Wind Valley on the southeastern edge of the property, saying the impacts would be too drastic in the pristine and ecologically significant area.

The 239-page report outlining the hearings and the board decision showed the complexity of the land in question and the scope of the concerns that accompanied the development — even those voiced by Three Sisters. They included wildlife habitat, affordable housing, the threat of collapsing old mine shafts, infrastructure costs, water use and protection and the strain of so much change on one small town.

But even the board said it couldn’t peer into the future and truly understand how the project would play into the greater whole when it came to development and growth in the Bow Valley. It was tasked, it said, with evaluating the Three Sisters plan — something described as “conceptual in nature.”

Parks Canada, one of the organizations that spoke at the hearings and described its position as “neutral,” had serious concerns about the potential impacts on wildlife and the wider ecosystem.

It called the environmental assessment carried out by Three Sisters inadequate and said habitat models and the data used for those models were “questionable.” Parks Canada, along with others, said there needed to be clearer understanding of cumulative effects over a larger area and warned the Bow Valley was in danger of being “overdeveloped.”

The board itself expressed concerns about how much is too much and said there is “kind of ‘maximum carrying capacity’ for change in societies and ecosystems,” but it ultimately rejected the need for a proper assessment before considering the development, or to wait for the town to finalize its in-progress master planning document.

Others worried about how the project would provide affordable housing in an area already struggling with soaring costs and an influx of wealthy outsiders, but the developer assured the board that over 60 per cent of the units would be “low and modest cost housing” with plenty of staff accommodation and rentals.

Critically, the board rejected suggestions from some hearing participants that its approval would prevent the town from rejecting more specific proposals brought before council for the project.

“The board is satisfied that such an approval would not denude the town of its authority under the Planning Act, nor would it preclude the effectiveness of public participation processes in the town, owing to the need for both the approval of the board and the approval of the town before the project may ultimately proceed,” it said.

The board did not impose a time limit on its decision, even though it had the power to do so.

“This is an unusual piece of land and it’s unusual intervention by the provincial government that doesn’t put any sunset clause on the application of the [board] decision, which was, in retrospect, kind of strange, given how things change in the world,” says Frank Liszczak, a former manager of planning and development for the town.

More than 32 years later, under ownership that has changed four times, that decision still stands and covers a development that bears little resemblance to the scheme that first gained board approval.

“The approval by the province on this is premature at best, and done so without any real knowledge of the long term effects,” Casey says. “ And that, to me, is tragic.”

The project today, separated into two distinct areas, is mostly a residential development. No big resorts. No big golf courses. Certainly no amusement park. The Wind Valley, where that original group of owners wanted to first develop a tourist enclave amidst the forest and hills, was removed by the board decision and the plans shifted.

Sean Krausert, the current mayor of Canmore, says the town annexed the land in 1991 knowing it would be developed.

“The division starts with a different understanding of how they would be developed,” he says.

As late as 1997, the original owners were proposing resorts that would spread across their patch of the Bow Valley, including a cornerstone 400-room Marriott Hotel to be built in the first phase, three lodges ranging from 30 to 120 rooms and timeshare units, with commercial developments, golf courses and housing to follow.

Three Sisters also proposed to develop what it called a “tour mine” using the historical features from the old coal operations.

But it had drastically increased the number of residential units since the time of the Natural Resources Conservation Board hearings, and the visions continued to change as the owners struggled to finance their plans.

Casey says when he showed up on council in 1995, he was helping oversee a “fractured community.”

“From the developer side, they felt that when parts of the development were approved by the [board], well that was a carte blanche — a go ahead, do anything you want scenario,” he says. “And so that, again, created a great deal of friction.”

Liszczak, the former manager of planning and development who started with the town shortly after Casey in 1996, thinks some of that friction likely came from within the company.

“I don’t think Three Sisters really had a good handle on what they wanted to do with the land,” he says. “Once they got that [board] decision, they kept changing their mind as economics changed, as their cash flow changed and the town councillors changed. Probably more importantly than anything else, as the information about wildlife movements evolved over time.”

The type of resort development first envisioned requires patient money, Liszczsak, who went into private practice as a planner after working for Canmore, says, the kind that can stare down loss and uncertainty and wait for the payoff. He says it wasn’t there.

Some of the friction, including a looming court battle over what exactly was approved by the provincial board, ended with a settlement in 1998 that would have capped the numbers of units and hotel rooms the developer could build.

The land was bought in 1999 by TGS Properties Ltd., and then morphed into Three Sisters Mountain Village, which brought on additional corporate shareholders. In 2007, management of the project fell to East West Partners and the ownership once again shifted to include investment bank Morgan Stanley with a majority stake.

Two years later, in 2009, Three Sisters Mountain Village filed for bankruptcy.

The first report of the court-appointed receiver cited a sharp downturn in the demand for recreational property, a surplus of properties in Canmore, a complex and lengthy approval process, limited cash flow and the “significant funding” required to maintain operations and complete development as reasons for the company’s demise.

The receiver tried in vain to see the project through as well, but it eventually unloaded the property in 2013 after Canmore town council rejected its area structure plan for the lands.

The terms of that sale were sealed by the court, but the purchase involved money owed to creditors. Two of those creditors were men who had been involved with the project for years and who just happened to be the new owners — Blair Richardson and Don Taylor.

Richardson and Taylor are two constants in a story that has few.

Taylor and his family are well-known in Calgary, with the name on everything from the Taylor Family Digital Library at the University of Calgary to the Taylor Family Polar Bear Sanctuary at the zoo.

Don Taylor made his fortune building Engineered Air — a heating, ventilation and air conditioning equipment manufacturer of which his son David is now president, and is also a shareholder in Three Sisters.

Richardson, based in Denver, Col., spent his career working in investment firms, including Morgan Stanley — the one-time majority owner of Three Sisters — and has run Bow River Capital since 2003.

Both have links to the Three Sisters land since at least 1999, with varying levels of involvement throughout the changing ownership groups.

Canmore had evolved over the decades since the mines closed and as the world shifted its gaze to the Bow Valley. An environmental conscience settled in and more research and thought was going into how to live with wildlife and protect habitat.

Walking up the forested hills from Canmore to a vista that overlooks the valley and town in December last year, Leanne Allison and Tracey Henderson, both with an organization called Bow Valley Engage that sprang up to oppose Three Sisters, talk about how the town has changed.

Henderson says the area where they’re walking, across the valley from Three Sisters, points across the valley to its south side, now built out, and says it was largely undeveloped when the board made its decision.

“A big part of the kind of cultural identity of Canmore, and I think that’s why we saw so many people come up for the public hearing … is that we’re proud of coexisting with things like grizzly bears and wolves,” Allison says. “And we’ve actually developed ways of doing that that are being shared around the world.”

“Now, in 2023, it’s a whole different story,” she says.

Central to the ongoing tension within the community — and a strict condition of the Natural Resources Conservation Board decision — was the need for wildlife corridors through the Three Sisters lands.

It’s important not just for the legal obligation, but for how critical the area is for wildlife.

“The Bow Valley is one of few very important east-west connectors in this broader 3,200-kilometre region called the Yellowstone to Yukon region, which is one of the most intact mountain ecosystems remaining in the world,” Hillary Young, with the Yellowstone to Yukon Initiative, says.

“We are worried about human-wildlife conflicts going up, and the ultimate risk is that wildlife who have used this valley and this habitat for thousands of years may no longer come to this valley,” she adds, referring to situations when people and animals cross paths, often to the detriment of the animal.

Her organization released a cumulative impacts study in 2022 that showed recreation and development greatly increase the risk of those conflicts in the Bow Valley.

“The accumulation of wildlife risk in the valley is an example of the tyranny of small decisions, whereby environmental degradation occurs not by design but through the unintended consequence of numerous small decisions made in isolation from one another,” it reads.

Another study, in the journal Movement Ecology, looked at grizzly bears and grey wolves moving through the Bow Valley and found current development in the valley “reduced the amount of high-quality habitat between two mountain towns by more than 35 per cent” and reduced connections they travelled by 85 per cent.

That’s without Three Sisters.

Jon Jorgenson was on the frontlines of the corridor debate in the ’90s, working as a senior wildlife biologist for the province in the Bow Valley. He says the board decision had a serious impact on his work.

“Suddenly pressure came at senior levels that, hey, we need to get this corridor resolved, we need to get an approved wildlife corridor because we want to move forward,” he says in an interview.

“And for myself, what it meant was having to approve a wildlife corridor when we didn’t have adequate information. Because we didn’t know very much about wildlife movement in those days.”

He says there was support for his work to gather and share that information within the Alberta government, but at the end of the day, there was pressure to get something done.

The result was a corridor — essentially a protected stretch of land for animals to travel — approved in 1998, that he says was on slopes too steep for wildlife and that didn’t take into account how animals move through the region. Even as that knowledge deepened, the corridor remained. Jorgenson saw an unfair playing field.

“For Three Sisters, things changed. They could modify however they deemed fit,” Jorgenson says. “And we did not have … let’s just say senior levels of government were not prepared to go back and change the agreement that they had made.”

With the size of the development now approved, he questions whether even the best corridor would be effective.

“What good is it to have a functioning wildlife corridor that allows grizzly bears to move through the valley if they are just going to get into conflict with people, and they end up being destroyed or removed,” he says. “You don’t have a functioning wildlife corridor in an instance like that, you just don’t — anything that ends up in the Bow Valley ends up dead.”

That 1998 corridor stuck, but the connection with the rest of the property was a problem. Another proposed corridor down the valley and then east along the southern edge of the property didn’t align and the science was changing, with more attention being paid to the steepness of slopes and the preferred routes of creatures large and small.

Even as the company fell into bankruptcy, the receiver pushed to resolve the corridor issue so it could improve the value of the land for any potential buyers. At first one of the creditors, a company owned by Taylor called Airstate, resisted the idea.

The company said it “is of the opinion that the receiver should not participate in the process set out by the province to resolve the delineation of the wildlife corridor.”

By 2012, however, the receiver noted Taylor and Richardson were working on the corridor issue themselves as creditors in the bankruptcy, bringing proposals to town council while the receiver kept the province up to speed.

They kept at it after they re-purchased the property the next year.

In 2018, the province, under an NDP government, rejected their plans for a corridor. But after the United Conservative Party (UCP) took power in 2019, those fortunes changed. The province suddenly approved the corridor and cleared the final hurdle from that board decision 27 years earlier.

Ollenberger defends those corridors, saying they will be effective in allowing wildlife to move through the area and that the developer will include fencing to reduce interactions between humans and that wildlife.

“Human use management of these corridors is key,” he says. “Not only did we make the wildlife corridors wider, not only did we put in an additional crossing structure in the Trans Canada Highway, but we are going to fence them.”

Strolling down Canmore’s main street, there is still a quaint feel — though the SAAN store, a small-town Alberta staple, is gone — and there’s no shortage of paintings, coffees and puffer jackets for sale. It’s hard to imagine a miner from the ’60s knowing what to make of the tuna ceviche with passionfruit served at Crazyweed.

Driving out of downtown and along Three Sisters parkway, earlier residential phases built on their land are testament to the wealth of those who buy here. Weekend cabins that dwarf most homes line the prime habitat that hugs the Bow River.

In 2023, the median price of a home in Canmore climbed to $1.7 million, according to data from Royal Lepage. And according to the latest data from the province, the vacancy rate for rentals was 0.2 per cent in 2022 — a 93-per-cent decrease in vacancy from the previous year.

That leaves a lot of locals, the ones who haven’t already left, worried.

“They are not fulfilling any community needs through this development, zero,” Allison, with Bow Valley Engage, says about the housing being built by Three Sisters.

When the project was approved in its nebulous form by the Natural Resources Conservation Board, the developer at the time made promises about affordability. Even then, the valley was struggling with rising costs and limited vacancies.

But those promises weren’t written in stone. It said 50 per cent of the housing units would be “available at relatively low cost” on small lots or as multi-family dwellings. Approximately 30 per cent, it said, would be in the “mid-price range.”

“It didn’t actually say: here’s the price points,” Ollenberger says, stressing it was more about the forms of housing to be built.

“People would pick up the torch, forget the word forms and say, ‘Well, they promised us 50 per cent affordable housing and now it’s down to 10’, when it’s actually a very apples-to-oranges comparison.”

Three Sisters did set aside land for the town to use for affordable housing and Ollenberger says there will be options, particularly in a commercial development it is currently building that’s not part of the controversial area structure plans.

It’s not enough to tame the housing crisis that extends from Canmore and into the national park, with workers struggling to cover costs and businesses struggling to attract and keep workers. But no one really knows what could.

“The reality that we have today is we’ve really replaced one extractive industry — coal — with another — housing and tourism,” Josh Welsh, a former Canmore town planner who helped organize the public hearings into the current projects, says. “And some could argue that the latter is more intractable. Because once you build the roads, once you bring the people, once you build the houses, you can’t really take them away.”

Ever since the 1992 approval, and even before, there was a tension at play that encompassed all the others — the ability of the town to make decisions about its future.

It was there when the board assured residents and the town the approval would not “denude” local authority. It was there as the town rejected proposals and went to court several times. It was there as the developers pushed back and pushed on despite the headwinds, waving the provincial approval as a beacon in their financial storm.

“The concern of the community, and my own concern, is that the current scope of what is being proposed and planned far exceeds what community members think is appropriate for that landscape,” Sarah Elmeligi, the local NDP MLA and a biologist, says. “And what science suggests is appropriate for that landscape as well.”

She says this is a case of “massive provincial overreach” into municipal governance.

Even when the development was in receivership, usually staid reports from the receiver brimmed with frustration at its dealings with a town that clearly did not want the project to move forward as pitched.

“The receiver’s dealings with the Town of Canmore,” it said matter of factly in its third report to the court, “have been challenging.”

In 2017, the town council sent Three Sisters packing when it rejected an area structure plan for the entirety of the remaining lands. Council said it wanted that plan broken up into two separate plans before it would even consider it.

Then, in 2020, as Three Sisters returned with its two plans as requested, the town showed up in force to oppose it. Public hearings stretched over seven days as speaker after speaker outlined their concerns, and a few — nine out of over 260 — offered support.

Haimila spoke of the extensive undermining that sits below the surface and what he sees as threats of collapse. Snow Jr., from the Stoney Nations, spoke of a lack of consultation and the significance of the land.

The whole litany of issues bombarded council for days.

On the last day, it heard from one of the owners, David Taylor, the son of Don Taylor and a Three Sisters director.

“I will be honest that it has been difficult to listen over the past few days to so many people who have labelled us as greedy developers and portrayed us as speculators,” he said.

The issue was too polarized, there was no room for discussion and those who supported the project felt like they could not speak up, he told the packed chambers. The land, he said, was long meant to be developed.

“[Three Sisters Mountain VIllage] has no intention of walking away from this project,” he said.

Council rejected the plans anyway in 2021. First the Smith Creek area structure plan on April 27 and then the Village area structure plan on May 25.

By July, Three Sisters appealed to the provincial Land and Property Rights Tribunal to overturn the rejections.

By December 2021, the developer launched its $161-million lawsuit against the town and against individual councillors for abuse of office. It called their actions “de-facto expropriation.”

Three Sisters, no matter the specific owners, has been working to develop its land for over 30 years, and seen approval by the Natural Resources Conservation Board and various approvals and support by the province and even the town. The frustration it felt with the 2021 rejection is palpable in its lawsuit.

“The extent and degree of that resistance has been unwarranted, unlawful and beyond the legitimate circumscribed interests and entitlement of Canmore,” reads a portion.

The developer said it poured $11 million into developing the two plans in discussion with the town. It argues in its lawsuit that based on its working relationship with town administration and guidance from council, it expected an approval, perhaps with the usual modifications as plans are narrowed down.

The town, councillors and mayor, in a statement of defence, argued they were acting in good faith and “in accordance with their legislated powers and obligations.”

Naming individual councillors and the mayor was, the town argued, an “effort to coerce elected individuals to accede to [Three Sisters’] wishes at all costs, and regardless of any other relevant considerations.”

That lawsuit is still winding its way through the courts and continues to hang over council chambers, despite an election that replaced three of the named councillors and the mayor. It’s why three named councillors who still have their jobs were forced to abstain from the vote approving the plans late last year.

Casey, the former mayor, says even those who aren’t named as defendants are left to worry about being sued if they speak out.

Ollenberger says the lawsuit is still active, but the company will reconsider the amount of damages sought since the project is now moving forward. He rejects the notion it is designed to stifle dissent and bend council to the company’s will.

The developer also won at the property tribunal, which ruled the area structure plans were consistent with the Natural Resources Conservation Board decision and Canmore would need to approve them. Canmore appealed that decision to Alberta’s highest court and lost at the beginning of October 2023 — sealing its fate.

The tribunal found the company’s plans were broadly consistent with the Natural Resources Conservation Board decision in 1992.

The Court of Appeal did not deal with the substance of the plans, but only whether the tribunal erred in its decision, and found no legal failings.

“As unfortunate as this process has been, whether it be the land and property rights tribunal followed up by the Court of Appeal, there’s now certainty and clarity, not just for Three Sisters, but also for the town of Canmore,” Ollenberger says.

The projects are approved, the development is happening and those who think they can simply say no have realized that’s not an option and maybe never was. Ollenberger thinks it might have been helpful if the “crisis moment” came sooner.

“So the focus will shift, I think, relatively quickly from instead of talking about if the project should go forward — which was a mistake for many years to have that as the focal point — to how does the project move forward?”

In November last year, residents opened copies of the Rocky Mountain Outlook newspaper and found a full-page ad that acted as an open letter to Canmore, warning of the high costs of dissent.

“Three Sisters will continue to pursue a civil court case against the Town of Canmore, which when issued sought $161 million in damages for the decades of obstruction of the project, now determined to have been unlawful,” Richardson, one of current owners who has held varying stakes in the project over the years, wrote.

“When this matter is resolved, it could have the potential to severely impact the financial stability of the town and residents’ tax obligations.”

The letter called protestors who showed up at the Calgary home of Don Taylor shortly after the project cleared town council “immoral.”

Ollenberger says Richardson was frustrated.

“I’ve talked to him about this. And he would like to see things just move forward in a productive professional way,” he says.

It was a visceral reminder of the frustration and acrimony on both sides of the development debate.

Elmeligi, the MLA, thinks there is room for development on the land and compromise between the two sides, but the scale would need to change, the corridors expanded and the areas most impacted by underground mining avoided. She also acknowledges it will be difficult to sit down and have those deep conversations.

“There’s just so much emotional baggage that comes with something like this,” she says.

“Everybody needs to be able to meet in the middle, which means everybody has to move a little bit.”

Bow Valley Engage continues to push against the project, including with a letter-writing campaign that Elmeligi says has inundated her office. It’s calling on the province to step in and protect the land once and for all.

And in December, the Stoney Nakoda filed its own lawsuit against the town and the province for granting approval without proper consultation on a project that would impact its Aboriginal and Treaty Rights.

It wants the recent approvals overturned and the province and town to engage in consultation before any new approvals are issued.

William Snow, who is in charge of consultations for the nations and the point of contact on Three Sisters, declined to be interviewed for this article.

The fight over the Three Sisters lands isn’t just one of development and bureaucracy, it’s a clash of values that seem incompatible. Who gets to live in Canmore? How much care and attention should be paid to the wildlife and ecosystem? Can tourism co-exist with it and at what scale? How much is too much?

It’s about the pace of change in a place of timeless convergence, where the animals plot their way across an often unforgiving environment, full of rocky obstacles. A place that was long overlooked as it serviced the trains and tourists on their way to Banff and now finds itself marketed and coveted as an equal.

Sacred to some. Profitable to others.

Haimila still begrudges the fact there was big change on the horizon when the miners sold those $50-lots for a pittance.

“If they would have known 10 years later, what was going on? They would have tripled their money,” he says.

The long saga of the Three Sisters land has seen so much change and so many plans. Jorgensen says the plans that were finally approved are larger than previous plans in 1998 and again in 2004, and he wonders what it was all for.

“I think we achieved a lot, but at the end of the day, when you just look at the scope of what’s going on there and the amount of people that are moving into the Bow Valley — I just, I wonder whether or not all that effort has been worth it,” he says.

Updated on Feb. 5, 2024, at 8:07 a.m. MT: This story was updated to correct the year Three Sisters Mountain Village submitted two separate plans for its properties to the Town of Canmore. Those plans were submitted in 2020, not 2021.

Updated on Feb. 6, 2024, at 1:44 p.m. MT: This story was updated to clarify the details of two separate decisions: one from the Court of Appeal and one from the property tribunal. The Alberta Court of Appeal decisions didn’t focus on the substance of the proposals, only the processes that approved them. Its focus was distinct from that of the property tribunal.

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

For our last weekly newsletter of the year, we wanted to share some highlights from...

The fossil fuel giant says its agreement to build pipelines without paying for the right...