The Narwhal’s in-depth environmental reporting earns 11 national award nominations

From disappearing ice roads to reappearing buffalo, our stories explained the wonder and challenges of...

One hundred kilometres west of Calgary, the peaks of Alberta’s famed Three Sisters stand guard over some of the most desirable land in the province — sought after by humans and needed by bears, wolves and other wildlife to survive.

The town of Canmore, set in the shadow of the Sisters, now faces a decision that could change the community for generations of humans and animals alike.

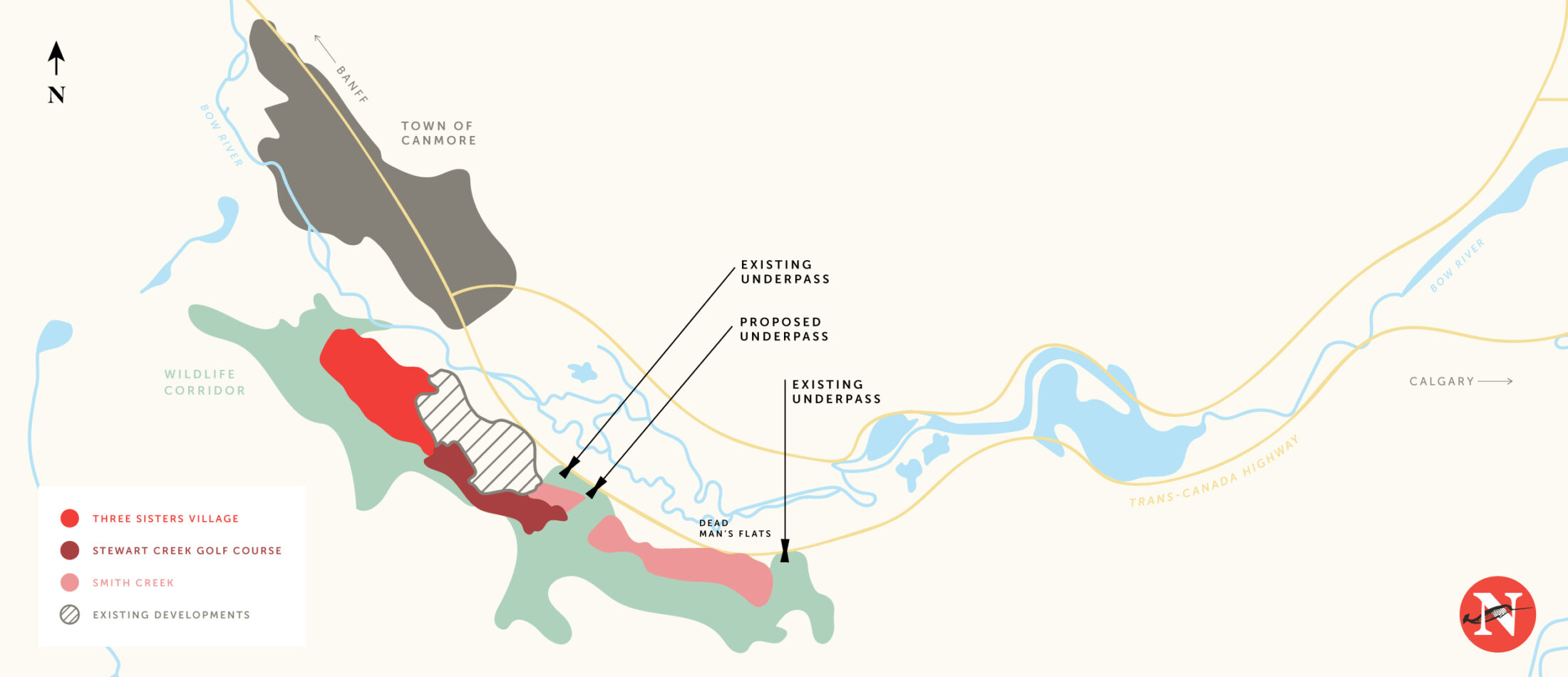

Canmore town council is weighing a proposal from a Calgary-based company called Three Sisters Mountain Village to build two new neighbourhoods on privately owned land on the town’s east side. The developments — Three Sisters Village and Smith Creek — could roughly double Canmore’s population and extend its footprint along the lower slopes of the valley as far as Dead Man’s Flats, about 10 kilometres from Canmore’s Main Street.

Together, plans for the two developments include housing for up to 14,500 people, along with a hotel, spa, arts centre, space for a school, cycling and walking trails, commercial areas, employee housing and a commitment that at least 10 per cent of new multi-residential homes will be affordable housing.

New neighbourhoods would help alleviate Canmore’s chronic housing shortage and create much-needed commercial space, but would also add significant pressure to the already fragile co-existence between wildlife and humans in the Bow Valley.

“If we don’t get it right when we do this, this is really our last chance. There’s no going back,” Hilary Young, senior Alberta program director for the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, told The Narwhal.

Hilary Young, senior Alberta program manager for the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, is among the Canmore residents worried about how large new developments will impact wildlife in the region. At a recent virtual town hall on the issue, more than 90 per cent of 240 participants opposed the developments. Photo: Leah Hennel / The Narwhal

After years of national and provincial involvement, the decision now rests with Canmore’s town council. If council approves the proposal after a second and third reading — mandatory deliberations that councils must go through to pass a bylaw in Alberta — the project will get a green light.

Council will also have to extend the town’s growth boundary into land currently designated as a conservation area to accommodate the Smith Creek development. If the proposal is approved, this step is anticipated.

In early February, Canmore’s town council voted unanimously to approve the first reading for both new neighbourhoods. Council will debate and vote on the proposal at the second reading, expected to take place on April 27.

In March, council opened a virtual town hall for members of the public to voice their opinions. Over six days, more than 240 residents of Canmore and representatives of the Stoney Nakoda Nation appeared via Zoom. Some came with Powerpoint slides and planned talks; others opened in prayer. Even children spoke.

More than 90 per cent of those who attended opposed the development. Town representatives said it may be the largest turn-out for a public hearing in Canmore’s history.

“It boils down to too much risk — financial risk, public safety risk and ecological risk,” Lindsey Marchessault, a local lawyer and governance expert, told council. She said she’d given birth to her daughter seven days earlier but felt it was important to speak out about decisions that would affect her children’s future.

A spokesperson for Three Sisters Mountain Village said the company has sought a ‘balanced approach’ in its plans, and has agreed to numerous ways to reduce its impacts on wildlife. But critics say the proposed wildlife corridor — essential for animals making their way through the region — is too steep and too narrow in parts. About 11 per cent of the proposed corridor is located on slopes with a steepness equivalent to a black diamond ski run. Map: Alicia Carvalho / The Narwhal

Karsten Heuer, an independent biologist who lives in Canmore and a former president of the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, also joined the virtual town hall. He told council the development will lead to more human-wildlife interactions in the Bow Valley and cut into liveable habitat for animals that make their homes in the valley.

“This is one of the last mountain ecosystems in the world where we still have all the native animals that were here when Europeans first started colonizing. It requires incredible awareness to maintain that,” he told The Narwhal.

He said he fears the consequences will extend beyond the province if the development impedes access to the critical wildlife corridor that stretches from Yellowstone National Park through the Bow Valley and up into the Yukon.

“Then you’ve lost not just the character [of the town], but the integrity and function of a much larger ecosystem,” said Heuer, who, in 2016, stepped down from a community advisory group led by the developer because he felt scientists’ voices were being ignored.

Residents like biologist Karsten Heuer are concerned a unique diversity of wildlife is already facing intense pressure from the bustling town of Canmore. “This is one of the last mountain ecosystems in the world where we still have all the native animals that were here when Europeans first started colonizing,” he said. Photo: Leah Hennel / The Narwhal

At the end of the public hearing, David Taylor, the president of Three Sisters Mountain Village, said the company has worked with council and residents over five years to develop plans that fit Canmore’s municipal development and integrated transit plans.

He told the audience the lands are privately owned and will be developed.

“We don’t believe that the status quo is a solution,” he said.

The proposal in front of council is the latest chapter in a debate that has simmered for three decades: how can a booming mountain town balance the conflicting desires of wildlife and humans who want to live in this picturesque part of the province?

Canmore’s unique topography, on the lower slopes of the Bow Valley beneath the famed peaks of the Sisters, draws both humans and wildlife. The valley bed sits at an unusually low elevation for the Rockies, making for warmer temperatures and lusher conditions than many other areas of the province. A gravel-bed river runs along the valley’s flat bottom. This provides an accessible — and visually dazzling — route through the mountains. Just up the road, Banff National Park boasts many similar features, as well as large swaths of impermeable rock and ice.

Evening light on the Rocky Mountains surrounding Canmore showcases the visually dazzling peaks that draw legions of tourists to the region year-round. Photo: Leah Hennel / The Narwhal

That rock and ice makes life more difficult for many animals. “Fifty per cent of Banff is worthless for most wildlife species,” Mark Hebblewhite, professor of wildlife biology at the University of Montana, told The Narwhal.

Species that live, eat, sleep and mate in and around Canmore include grizzly and black bears, elk, cougars, wolves, snowshoe hares and owls. They rely on the Bow Valley as a critical wildlife corridor that stretches for 3,200 kilometres. Such a large corridor is essential for maintaining healthy wolf and grizzly bear populations, according to wildlife biologists.

Grizzly bears used to live as far south as Mexico, explained Heuer, the wildlife biologist based in Canmore. Over the last two centuries, their habitat shrunk as humans moved in. Grizzly bear populations broke into islands scattered across the continent, from which bears were unable to migrate to find food or mates. Bears became genetically isolated, leading to inbreeding, deaths and even the extinction of local populations of grizzly bears.

“If you look at the Bow Valley where Canmore is situated and then zoom out to this 30,000-foot view from above, what you see is the potential for Canmore to cut off a peninsula of grizzly bear activity,” Heuer said. “If we don’t get it right here, we create another island that, over time, is going to get eaten away.”

Grizzly bears in Canmore frequently interact with humans, often leading to harsh outcomes for bears. Almost 100 hundred bears have been killed or relocated from Canmore over the last 20 years, including Bear 148, seen here, who was known locally for her close encounters with residents, and who was ultimately shot by a trophy hunter in B.C. Photo: Leah Hennel / Calgary Herald

Established as a coal-mining town in 1884, Canmore emerged as a resort destination when the town played host to venues at the 1988 Winter Olympics. Since then, it’s been in a state of near-constant boom. The population has tripled over the last 30 years. On weekends, roads are packed with people and cars, while trails are busy with people and bikes. During the pandemic, Canmore has proven even more seductive for visitors, and is now one of the province’s most popular year-round tourist destinations.

As it grew, Canmore became a world leader in implementing science-based solutions that allow bears and humans to coexist in the valley, according to Adam Ford, an assistant professor and Canada Research Chair in Wildlife Restoration Ecology at the University of British Columbia Okanagan. The town discouraged fruit trees on private property and implemented bear-proof garbage-disposal systems. In Canmore and Banff, animal-crossing systems help bears — along with wolves, elk and other species — traverse highways safely.

“We don’t see this anywhere else in North America, and that’s something that Canmore should be proud of,” Ford said in an interview.

The wildlife corridor proposed by the developer includes links to two existing wildlife underpasses under the Trans-Canada Highway, and one new underpass. Wildlife underpasses and overpasses have been used throughout Banff National Park to allow animals such as bears to safely cross the busy highway. Photo: Highwaywilding.org

Efforts are paying off. After grizzly bears were declared a threatened species in Alberta in 2010, their population increased from between 700 to 800 one decade ago to an estimated 865 to 973 today, according to figures reported by the province last month.

But despite the success of some measures, the relationship between people and bears in this area is an increasingly delicate balancing act. Almost 100 hundred bears have been killed or relocated from Canmore over the last 20 years, compared to six in nearby Banff National Park. In the best-known case, Bear 148, who’d become famous in the valley for her unusually close encounters with humans — the subject of a podcast by The Narwhal — grew frustrated after an incident with an off-leash dog. Due to fears for her safety and that of humans, Bear 148 was translocated to Kakwa Wildland Provincial Park, a territory unknown to her. Within days, she wandered into British Columbia, where she was shot and killed by a trophy hunter on Sept. 24, 2017.

Animals face growing struggles to stay out of trouble in Canmore, even with protections in place, Ford said.

“They find themselves on the trail at night and somebody comes ripping down on a bike with their headlamp on,” Ford explained. The human bumps into the bear, even though the animal shifted to nocturnal behaviour to avoid humans.

“They try to get out of our way. It just gets harder and harder to find that space in a narrow valley where there’s more and more people coming,” he added.

Plans to try to keep wildlife safe despite the large influx of new residents that would come with two new developments include wildlife fencing, signage and ongoing education of residents and visitors. Residents of Canmore are already discouraged from growing fruit trees and the town has installed a bear-proof garbage-disposal system. Photo: Leah Hennel / Calgary Herald

The current proposal for the Three Sisters development grew out of the buzz of the 1988 Olympics. The following year, Calgary-based Three Sisters Golf Resorts Inc. purchased land in the Bow Valley and nearby Wind Valley. In 1991, the group announced plans for a massive project of golf courses and housing units on the sites. The scope of the proposal triggered a review by the Natural Resources Conservation Board which, in 1992, approved the application for the Bow Valley but not for the Wind Valley.

This decision stated that any changes to the original proposal would need approval from the town of Canmore.

The decision launched 30 years of debate about what to do with the property, and is the foundation of the current plan.

Proposals have come before town council several times. In 2004, council approved a proposal to build a resort center on the Three Sisters property with a golf course and accomodations. Over the following years, ownership of the land passed through different groups. The current owner, Three Sisters Mountain Village, repurchased the property in 2013. They’d previously owned it between 2000 and 2007.

The town of Canmore sits on the lower slopes of the Bow Valley, in an area at an unusually low elevation, meaning it’s often warmer and lusher than other parts of the province. That makes it appealing to humans and wildlife alike. Photo: Jaime Dantas / Unsplash

In 2016, the company submitted a new proposal to develop the lands at Three Sisters, having decided that a golf course was no longer viable (an unfinished golf course currently sits on part of the land). Council unanimously voted against taking the Three Sisters plan to a second reading.

Around the same time, the company applied to Alberta Environment and Parks to approve a wildlife corridor around the Smith Creek property — a necessary step before council could approve development on the land. In 2018, the province rejected the proposed wildlife corridor, concluding the space was “not satisfactory.”

Then, in February 2020, after the United Conservative Party came to power, Alberta Environment and Parks approved an updated proposal — to the surprise of the town’s residents and council. The company and the province said the plan expanded the corridor and portions were moved to slopes more suitable for animals.

The approved wildlife corridor wraps around much of the proposed development. It begins at an animal underpass that runs beneath the Trans-Canada highway near Dead Man’s Flats and sweeps up slope, enveloping a quarry and the Smith Creek property. It cuts back down slope to the highway where the developer will fund and build a new underpass for large animals. From there, the corridor extends about 600 metres along the highway to connect with an existing underpass.

The approved corridor sparked criticism from conservation experts, who said it failed to meet local guidelines that had been developed with input from experts, as well as federal and provincial governments.

Young, of the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservative Initiative, said the corridor is too steep and narrow in parts. Animals like wolves, grizzlies and elk prefer to travel on flatter slopes. About 11 per cent of the proposed corridor is located on slopes greater than 25 degrees, or about the steepness of a black diamond ski run, she said.

“The precautionary principle should be used so that we make a corridor that is as wide as it can be and as flat as it can be for wildlife into the future. And the corridor that was delineated just isn’t that at all.”

Grizzly and black bears, elk, cougars, wolves, snowshoe hares and owls all frequent the Bow Valley, which biologists say is itself a critical wildlife corridor that stretches for 3,200 kilometres. Photo: Leah Hennel / The Narwhal

Many of the town’s residents, along with conservation advocates, worry the development could set off a chain of events that will increase harmful interactions between humans and animals and affect the broader ecosystem.

“If you shrink the movement corridors all the more, you’ll get some decrease in movement,” said Stephen Herrero, professor emeritus of ecology at the University of Calgary and author of the book Bear Attacks: Their Causes and Avoidance. This will further reduce grizzly bear populations, he added.

An interagency study, released as a pre-print in February, found that wildlife connectivity in the Bow Valley has already declined significantly from pre-development times — it’s down 25 per cent for wolves and 21 per cent for grizzly bears. Researchers used a new form of modeling, based on wildlife transit patterns around Canmore and in uninhabited areas, to predict what will happen if more people and buildings are added to the terrain. According to the model, connectivity will drop another six per cent with the proposed expansion.

“The Bow Valley is already severely impacting wildlife habitat and movement with the current footprint,” said Hebblewhite, who, with Ford, is one of the study authors. “If we roll these developments out, we’re going to see continued reductions and degradation of the quality of the habitats.”

The dramatic landscapes of the Rocky Mountains have long made Canmore a tourist destination. The town’s desirability has led to a housing shortage and a high cost of living. It has also meant increased interactions between people and animals, as developments, which could help alleviate the housing shortage, push further into wildlife habitat. Photo: Leah Hennel / The Narwhal

He said people often mistakenly think of a wildlife corridor as a transit route, but the term also refers to places that wildlife use as a home base.

“In the modern world, corridors … are the leftovers of formerly contiguous high-quality, low-elevation valley bottom habitat that we’ve cut up and then we leave [wildlife] the scraps left on the table,” he said. “They have to kind of eke their existence around it.”

He said he is frustrated that after years of work to protect wildlife on the part of multiple agencies and levels of government, the responsibility has now fallen to the town of Canmore.

“There is an entire governance part of this about who actually gets to decide about what the future of the Bow Valley looks like when the Bow Valley has big implications nationally, provincially, and obviously for the town of Canmore,” he added.

In December 2020, Three Sisters Mountain Village put its current proposal to town council. Chris Ollenberger, the company’s director of strategy and development, said the plans are based on the Natural Resources Conservation Board’s 1992 decision.

“[The board] wanted to achieve a balance of environmental, social and economic impact from the project. They determined that a balanced approach was in the public interest for Albertans. And so we’ve continued to respect [their] decision,” Ollenberger said.

The two communities would be edged with fencing to prevent wildlife from entering — an approach used successfully alongside highways in nearby Banff National Park, but relatively untested around residential neighbourhoods for humans. One exception is Jackson, Wyoming, where a three-kilometre wire fence on the edge of the town prevents elk from wandering in from a nearby refuge.

As part of its proposal, the company submitted an environmental impact statement by Golder Associates. It recommends 100 mitigations that could reduce human-wildlife interactions in the area, including wildlife fencing, signage and ongoing education of residents and visitors. One of the chief aims is to keep humans from entering the corridor and using it to hike, cycle and let dogs loose. The company has agreed to the 100 mitigations, but it is unclear who will be responsible for enforcement.

Wildlife fencing along highways is one way wildlife fatalities can be prevented. Fencing is also proposed to surround the entirety of the two proposed developments in Canmore, something that is rarely done around residential neighbourhoods. Photo: Aerin Jacob / Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative

The effects on wildlife will be monitored and studied as the development is slowly rolled out in multiple stages over the next 20 to 30 years, Josh Welsh, who works in community planning with the Town of Canmore, said during the public meeting.

In his presentation, Welsh outlined what the town sees as the proposal’s strengths — and its weaknesses. He noted the Stoney Nakoda Nation was not consulted on the proposal. Long before Canmore was established, the Stoney Nakoda and other Treaty 7 Nations stewarded the Bow Valley, he said. “We’d all benefit from improving our engagement efforts with them,” he said.

At the public hearing, Bill Snow, a member of Wesley First Nation and a consultation manager at the Stoney Tribal Administration, called on council to deny the applications. The company failed to recognize the First Nations’ water rights, reverence for wildlife and the cultural significance of these areas, he said.

Elders Jackson Wesley and Roland Rollinmud also spoke at the hearing, sharing historical stories of the significance of the Three Sisters.

“Giving voice to the wildlife and habitat is part of the Indigenous stewardship role that the Stoney Nakoda have fulfilled for thousands of years. The voice that is missing from these project assessments is the Indigenous voice,” Snow said at the hearing. (Snow did not respond to The Narwhal’s request for an interview.)

“To not acknowledge, hear or understand the voice of Indigenous perspectives, that is the legacy of colonization,” he added.

He called for an independent environmental assessment and a cultural study of grizzly bear management in the Three Sisters area, similar to a 2016 study in Kananaskis.

“Culturally important species, like grizzly bears, have an important role in Stoney society,” he said. While most studies approach wildlife from a western science perspective, he said they should also take into account the Traditional Knowledge perspective.

In addition to residents who spoke at the town hall, more than 1,800 wrote letters in opposition. Among their concerns, they said the plan falls short of addressing Canmore’s need for more affordable housing. They questioned the financial impact on the town, though the initial assessment suggested it will be revenue-generating. Many pointed out that the development will be built on top of formerly mined areas, which could put roads and trails at risk of sinkholes. And they raised concerns about contributing to climate change.

In early March, the company posted a statement online addressing in detail the residents’ concerns, including with respect to the town’s population, wildlife corridors, sinkholes and property values.

“We have heard those who have offered input,” the company said in the statement. “However, we have been clear that we are not open to making further amendments to the provincially approved wildlife corridor, nor will we consider a ‘no development’ position.”

As development in popular tourism regions of the Rocky Mountains increases, pristine valley-bottom habitat is increasingly scarce. “We leave [wildlife] the scraps left on the table,” Mark Hebblewhite, professor of wildlife biology at the University of Montana, told The Narwhal. “They have to kind of eke their existence around it.” Photo: Karsten Heuer

Young, of the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, said she doesn’t expect the company to leave its lands undeveloped. But she wishes they would commit to a smaller project. “Even if we had a much smaller footprint and that smaller footprint was fenced, I would be much less concerned than I am now,” she said.

Ford drew a parallel between wildlife management in the Bow Valley and the Ever Given ship that became trapped in the Suez Canal in March. The margin for error is small, he said.

“[The canal] was a human-designed system, and it still went haywire. And here, we’re talking about squeezing animals into a canal of habitat,” he said. “And if humans can’t do that in the Suez Canal, how can we expect grizzly bears to do it in the Bow Valley?”

Update May 7, 2021, at 2:11 p.m. PT: Cougars and mountain lions are the same thing. This article has been updated to reflect that fact. Rawr.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

From disappearing ice roads to reappearing buffalo, our stories explained the wonder and challenges of...

Sitting at the crossroads of journalism and code, we’ve found our perfect match: someone who...

The Protecting Ontario by Unleashing Our Economy Act exempts industry from provincial regulations — putting...