‘Afraid of the water’? Life in a city that dumps billions of litres of raw sewage into lakes and rivers

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

When B.C. unveiled its signature CleanBC plan in 2018, onlookers noticed something suspicious: it was full of holes.

Although the plan included a specific target — to reduce emissions 40 per cent below 2007 levels by 2030 — it only laid out the measures to get about three-quarters of the way there.

By its own admission, the province had a climate plan but no credible pathway to implement it.

And while B.C.’s NDP government promised to fill in those gaps on a tight two-year timeframe, that deadline came and went on Dec. 5, 2020, without so much as a mea culpa from officials.

What gives?

Two words: fracking and LNG. (Okay, one word and one acronym…)

Both fracking and the development of liquified natural gas, or LNG, are incredibly carbon intensive.

Fracking is an energy intensive process used to extract natural gas from shale deposits deep underground. The process releases enormous amounts of methane gas, a potent greenhouse gas with a climate warming potential 25 times that of carbon dioxide on a 100-year timescale. Although B.C. has promised to tackle fracking’s methane problem, an explosion in fracking operations, necessary to feed B.C.’s growing LNG industry, is making that impossible.

There are currently seven LNG facilities in various stages of planning, proposal and construction in B.C.

LNG Canada, the province’s largest LNG facility currently under construction, is expected to double fracking operations in B.C., according to the government. The much smaller proposed Cedar LNG facility is expected to require 5,276 new wells to be fracked in northeast B.C. over the next 30 years, based on calculations from the Wilderness Committee.

But high emissions from fracking isn’t the only factor behind B.C.’s climate gaps: LNG facilities are also extremely large emitters.

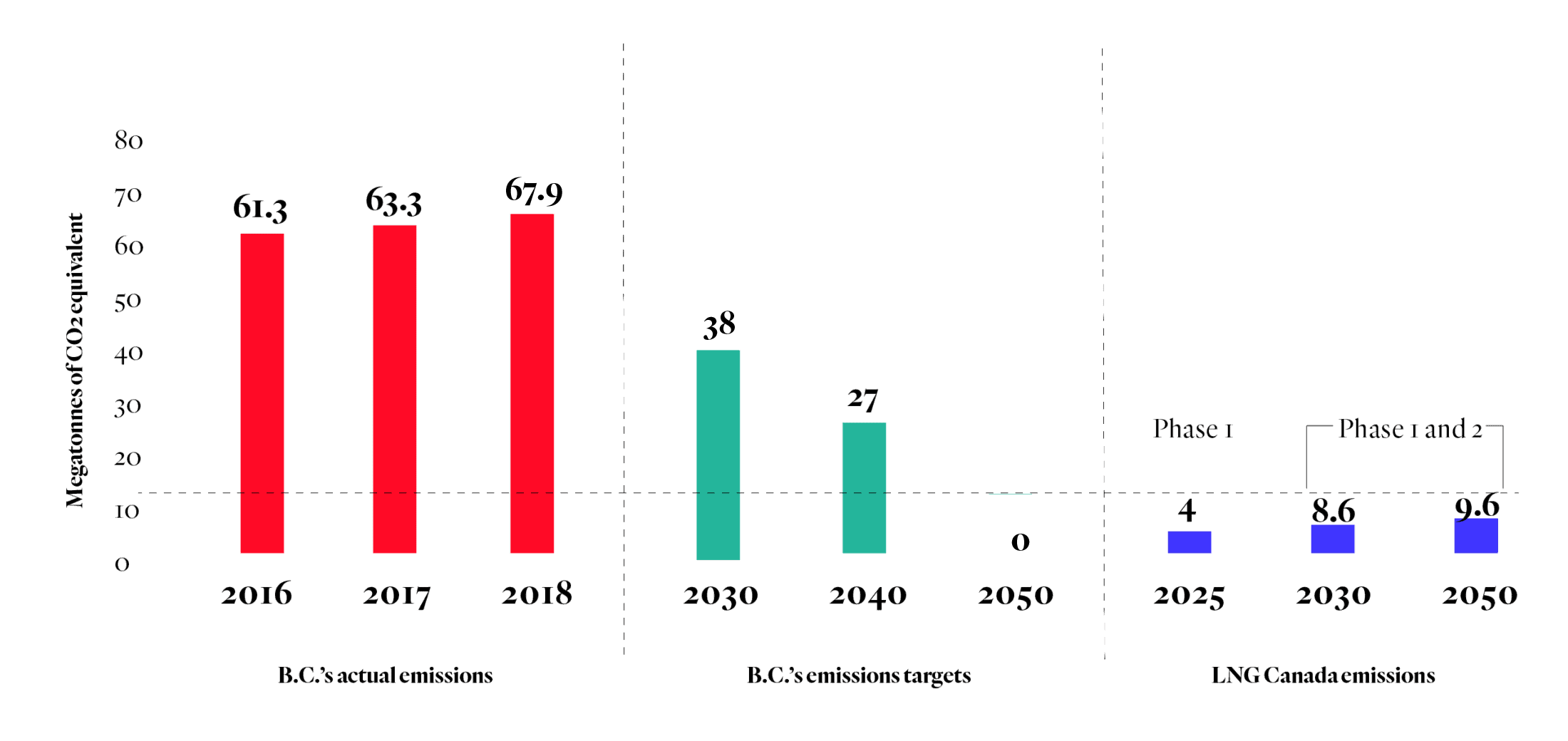

The first phase of the LNG Canada project in Kitimat will emit four megatonnes of greenhouse gas emissions annually, according to the provincial government — the equivalent of adding 856,531 cars to the road.

The Pembina Institute, however, has pointed out that when both phases of the project are built, the LNG Canada project would emit 8.6 megatonnes of carbon per year in 2030, rising to 9.6 megatonnes in 2050.

To put that into the context of B.C.’s CleanBC plan, the province has committed to reducing emissions to 38 megatonnes by 2030. And during his reelection campaign, Premier John Horgan vowed to make B.C. carbon-neutral, or have net-zero emissions, by 2050.

B.C.’s emissions for 2018 totalled 67.9 megatonnes, putting the province 14 per cent further away from its 2030 target than it was in 2007.

B.C.’s vow to make progress on these climate targets while also pursuing its fracking and LNG ambitions has left analysts, climate experts and environmental organizations scratching their heads.

And this question has put a spotlight on CleanBC’s missing measures.

“B.C. has missed every climate target it has set for itself and now is refusing to come clean on the impact of LNG on meeting its 2030 — let alone 2040 and 2050 — targets,” Andrew Gage, staff lawyer with West Coast Environmental Law, said in a recent statement.

Gage said the CleanBC plan as well as B.C.’s Climate Change Accountability Act, which requires the government to give bi-annual progress reports, were “supposed to put an end to this cycle of broken promises.”

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas with a climate warming potential 25 times that of carbon dioxide on a 100-year timescale. Global efforts are underway to curtail methane emissions, and as a part of Canada’s international commitments, B.C. set a goal of reducing provincial methane emissions 45 per cent by 2025, compared to 2014 levels.

But trying to meet that target at the same time as pursuing B.C.’s LNG ambitions is near impossible, experts say. Photo: Garth Lenz / The Narwhal

Here’s another important part of the story: B.C. has bent over backwards to attract the LNG industry.

One of B.C.’s biggest lures to attract multinational LNG companies was the introduction of a new suite of giveaways making fracking, gas liquefaction and export more profitable.

That 2018 fiscal framework, introduced just months before the CleanBC plan, offered LNG developers temporary relief from the provincial sales tax, new emissions standards so they had to pay less to pollute, the elimination of an LNG income tax and rebates for any penalties paid under the carbon tax if the facility met what B.C. deemed best-in-world standards (basically using more electricity).

This broad gesture of support for LNG did the trick. Just months later, LNG Canada — owned and operated by Royal Dutch Shell, Mitsubishi Corp., Malaysia’s Petronas, PetroChina Co. and Korean Gas Corp. — formally announced it would go ahead with a final investment commitment.

At the time, Shell Global’s Maarten Wetselaar said “the governments of Canada and British Columbia have helped to ensure that the right fiscal framework is in place to make sure that the pie is divided in a just and fair way.”

“And that fiscal framework leads to why we believe LNG Canada is in the right place.”

But that framework, so attractive to these corporations, cost British Columbia $5.35 billion dollars.

This support has further undermined B.C.’s climate credibility in the minds of critics.

Sven Biggs, Canadian oil and gas program director at the environmental organization Stand.earth, pointed out the province “gave almost a billion dollars in subsidies to the oil and gas sector in 2019 and 2020, twice what the government spent on their plan to fight climate change.”

A recent Stand.earth report found B.C. is “second only to Alberta in providing subsidies to the fossil fuel industry.”

“Fossil fuel subsidies have grown by a whopping 79 per cent during Premier Horgan’s term in office,” Biggs said in a statement released by a coalition of environmental organizations to note B.C.’s missed Dec. 5 deadline.

“It is difficult to see how this government will ever achieve their climate targets if they continue to heavily subsidize the very projects that are driving the increase in our emissions.”

Just the emissions from LNG Canada alone will make it very difficult for B.C. to meet its climate targets. Graph: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Canada has promised to phase out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies by 2025, a commitment that includes subsidies from provincial governments.

In recent months, and in the lead-up to the last provincial election, a new spotlight was shone on B.C.’s royalties regime when it comes to the oil and gas industry.

The B.C. government describes royalties as a portion of the profits earned by a producer of a resource, such as natural gas.

“Royalties differ from, say, corporate income taxes, in that they reflect a return to the provincial treasury when private development of a public resource takes place,” explains a March 2020 report from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

In B.C., royalty rates are largely based on the price of natural gas, which means the royalties collected by the government are lower when the price of gas is low.

While natural gas production increased significantly between 2008 and 2018, low gas prices were a “critical factor” in the decline in royalties collected over that same period, according to the centre’s report.

Royalty credits also played a role.

B.C. has a number of royalty credit programs, including the deep well royalty credit, which offers lower royalty rates to help offset the higher costs of producing gas from far below the surface, and credits for less productive wells to incentivize companies to keep those wells in production for longer.

These credits allow producers to reduce the amount of royalties they are required to pay the government, meaning the public is ultimately earning less from the production of its natural resources.

Read more: B.C. should disclose what fracking companies pay for publicly owned resources

The B.C. government was expecting to collect $153 million in natural gas royalties in the 2019-2020 fiscal year after accounting for royalty and infrastructure credits, which reduced payments by $381 million. The deep well credits accounted for $318 million of that reduction.

The total allowable deductions for royalty revenue in 2019-2020 was listed as $567 million.

The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives report notes that credits can also be saved and used to offset future royalty payments. According to the 2019-2020 report from the Ministry of Finance’s comptroller general office, there are $2.9 billion in outstanding deep well credits that can be used to reduce future royalty payments.

The oil and gas industry argues these royalty programs are good for business.

“Royalty credit programs, similar to other government programs such as the film and production tax credit program, are intended to maintain competitiveness, stimulate additional investment, and build a strong sustainable provincial economy,” the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers says in an August 2019 publication.

But that’s exactly the problem that some observers have with royalty credits — that they’re largely aimed at growing the industry, rather than phasing it out.

“If we’re going to be consistent with the Paris Agreement, we have to stop trying to do climate action on the one side and expand the oil and gas industry on the other side,” said Marc Lee, a senior economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and co-author of the centre’s report on phasing out B.C.’s fossil fuel industry.

“The amount of gas we produce must move toward zero, essentially, by mid-century, if not sooner,” he said.

Some of the royalty credits B.C. offers help offset the costs for oil and gas companies to reduce their emissions, such as the clean infrastructure royalty credit.

Lee said these measures amount to the government “paying for the companies to clean up their act by taking less royalties” and that methane emissions reductions should be handled by regulations.

But Sara Hastings-Simon, a senior research associate at the Payne Institute for Public Policy and research fellow at the University of Calgary’s school of public policy said in general, “it’s definitely fair to differentiate between subsidies that have strong green strings or even that are directly for emissions reductions … (and) general subsidies to increase production.”

It then becomes a matter of determining whether there’s a particular reason to make a public investment in emissions reductions, such as legitimate barriers that would prevent companies from taking those measures on their own, or just a case of transferring the costs of those reductions from industry to the public.

Another way to look at it is “the carrot versus the stick philosophy of emissions reductions,” Hastings-Simon said.

“You can give companies an incentive to reduce emissions. Of course, the government can also simply regulate them and require them to reduce emissions,” she explained.

But in cases where there may be political pushback against a certain regulation or ‘stick’ policy, governments may opt for the ‘carrot’ approach.

B.C. has promised to conduct a royalty review, but so far hasn’t moved forward.

— With files from Ainslie Cruickshank

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

Break out the champagne: Emma’s storied life and leadership in journalism has earned her the...