Celebrating 7 years of The Narwhal — and gearing up for the next 7

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

This is the first part of Carbon Cache, an ongoing series about nature-based climate solutions.

Well, it’s 2020 now and the techno-fixes are, rather unfortunately, not in.

No promise to geoengineer the skies or seed the ocean with iron or suck carbon out of the atmosphere has really come to fruition.

Yet, all along, Canada’s seaweed, dirt and trees have managed to do something that’s seemed impossible for the world’s most advanced technocratic nations: provide a legitimate, ongoing and cost-effective climate solution.

It’s with no irony that the world’s foremost scientific institutions are now recommending that to save nature what needs to be done is, well, save nature.

Perhaps the biggest boost to the idea of these so-called ‘nature-based climate solutions’ came in late 2017 when a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that the simple act of preserving wetlands, forests and grasslands could provide more than one-third of the emissions reductions needed to stabilize global temperature increases below 2 C by 2030 under the Paris Accord.

For countries looking to make quick climate gains, the idea of these nature-based climate fixes created quite the buzz.

Those findings also thrust Canada — home to 25 per cent of Earth’s wetlands and boreal forests, as well as endangered prairie grasslands and the world’s longest coastline — into playing a vital role in the global fight against climate change.

In early 2020, before the pandemic hit, hundreds of people from across the country gathered in Ottawa to discuss what a pivot to nature-based climate solutions in Canada might entail.

In a cavernous, bright conference room — booked and rebooked several times as numbers expanded from dozens to more than 400 attendees — Environment and Climate Change Minister Jonathan Wilkinson delivered the keynote address.

“Nature-based solutions give us the opportunity to tackle the challenges of climate change and biodiversity at the same time,” Wilkinson said to the more than 400 attendees.

In addition to its global climate commitments, the federal government has also set a goal of protecting 30 per cent of lands and oceans by 2030.

As part of its 2019 election platform, the federal Liberal Party pledged to spend $3 billion on nature-based climate solutions, including the planting of 2 billion trees and other land-use projects that naturally sequester carbon.

But at the conference another voice emerged to urge Canadians to think beyond the terms of “land-use” when it comes to nature’s role in the battle against climate change.

“Land relationship planning,” Steven Nitah, Dene leader and former Northwest Territories MLA, pitched to the crowd.

“Think of the phrase ‘land-use planning,’ ” he challenged the audience. “Land use — how we use the land. That doesn’t talk about land relationship planning.”

Nitah was the chief negotiator for Łutsel K’e Dene First Nations during the creation of Canada’s newest national park, the Thaidene Nëné National Park Reserve. The protected area, which covers 26,525 square kilometres of lakes, old-growth boreal forests, rivers and wildlife habitat, was uniquely designed with Indigenous land management in mind.

Steven Nitah, the Lutsel K’e Dene First Nation lead negotiator for Thaidene Nene National Park. Photo: Pat Kane

Nitah argued the concept of “land relationship planning” should enter the collective vocabularies of Canadians as the country imagines pathways forward for nature-based climate solutions.

It’s a phrase that got stuck on the tongues of the crowd for the rest of the conference as various experts pooled around tables and in the halls to discuss Indigenous protected areas and undervalued grasslands and how farmers are reimagining their relationship with soil to be better carbon stewards.

For climate solutions in particular, reimagining the relationship between humans and the land has never been more urgent.

Earth has regulated its own carbon cycle for eons, and it has only taken humanity 150 years to throw that cycle out of whack. Fortunately, the systems that balanced carbon in the atmosphere, in soil and the oceans, in living beings and inert rocks, still exist and still have the potential to recover. But doing that requires space.

“The capacity for nature to bounce back is incredible,” said Lara Ellis said of ALUS Canada, a national charity that works with farmers on projects that restore and benefit the natural landscapes, such as wetlands or good habitat for pollinators.

Protecting a forest is easier than recreating an entire forest, which itself is easier than building a machine to suck an equivalent amount of carbon from the air and store it. But the result, less carbon in the atmosphere, is the same.

The same holds for wetlands: artificial, built wetlands are both 150 per cent more expensive and significantly worse at storing carbon than simply protecting a wetland to begin with.

As climate change intensifies, many of the opportunities to harness nature’s own climate regulation systems are dimming.

Canada’s forests have begun to emit more carbon than they store as wildfires, droughts, pests and diseases rage within them. Coastal wetlands are shrinking and flooding, while inland ones are facing droughts and fires.

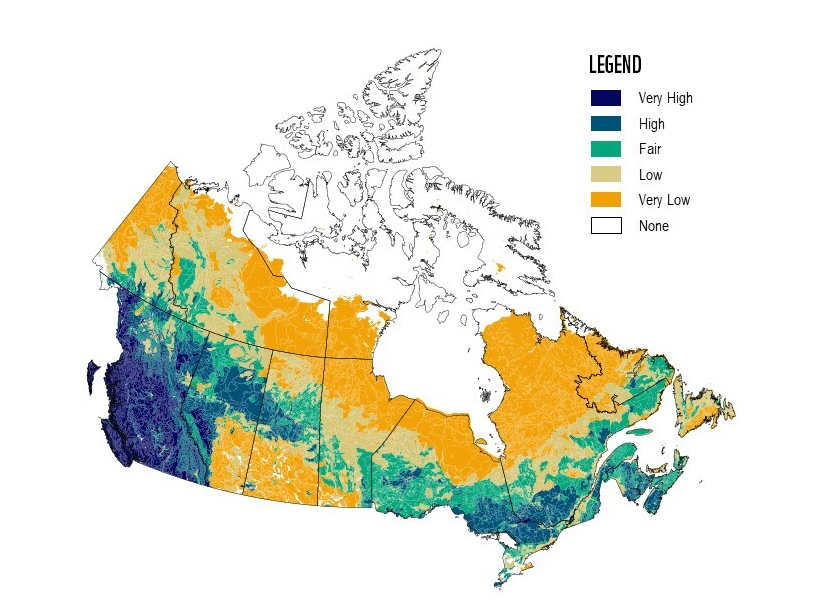

A map created by WWF-Canada for its 2019 wildlife protection assessment indicates the levels of forest biomass across Canada. Map: WWF-Canada

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that as many as 30 per cent of the planet’s species could be at risk — even in an optimistic 1.5 C temperature rise scenario.

Because of the urgency of the climate emergency, it is necessary to rethink conservation efforts not just under the banner of preservation but of restoration.

The United Nations has already declared the years between 2021 and 2030 as the “decade on ecosystem restoration” in the fight against climate and the growing threats to human survival.

“There is still time to work with nature, not against it,” said Patricia Fuller, Canada’s ambassador for climate change, standing before the Ottawa conference.

“But the window to do so is shrinking rapidly.”

In that shrinking window, scientists, Indigenous leaders, experts and policy advisors have begun identifying the most critical regions in Canada for the implementation of nature-based climate solutions.

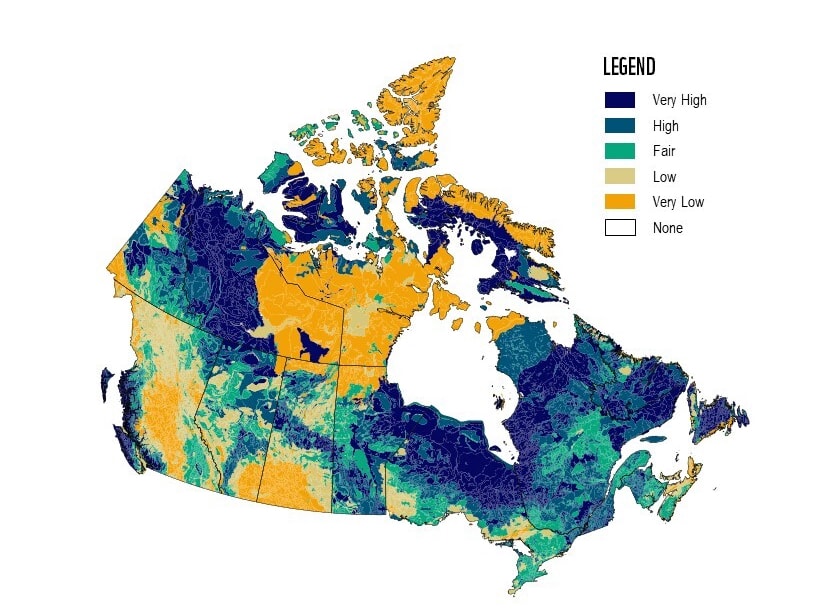

The concentration of carbon in the soil follows the boreal forest almost perfectly as it swoops across Canada, dipping from northern Yukon east around Hudson Bay and spilling out to cover much of Quebec, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador. It’s a globally significant store of carbon that holds almost twice the carbon of the planet’s tropical forests.

A map created by WWF-Canada for its 2019 wildlife protection assessment indicates the levels of soil carbon across Canada. Map: WWF-Canada

But with that storage comes the potential for release when the land changes: as much as 15 per cent of global carbon emissions come from deforestation. Destruction of peatlands accounts for 10 per cent as well, while farming accounts for another 10 per cent.

“The boreal forest is one of the largest intact forests in the world,” James Snider, the vice-president of science, research and innovation for World Wildlife Fund Canada, told The Narwhal.

“That establishes us in an important place to be leading the charge to show how nature-based climate solutions ought to be implemented.” But the boreal’s effectiveness at storing carbon has to do with what’s happening to its landscapes — logging, climate change and wildfires have all emerged as threats to the boreal and its carbon storage potential.

Canada’s boreal forest is a globally significant store of carbon that holds almost twice the carbon of the planet’s tropical forests. Photo: Stand.earth

Protecting those lands delivers other benefits to humans too. Forests purify the air, stabilize soil and provide places for recreation.

Wetlands are exceptional water filtration systems that also provide habitat for birds and amphibians, while absorbing excess water, thereby protecting land from floods.

Grasslands are home to the pollinators that keep agriculture alive. As an added bonus, the places that hold the most carbon are often the places that support the most biodiversity.

Protecting an area isn’t always enough, if climate change and its impacts are coming for the landscape and its wildlife regardless.

The solution, Snider says, is to make sure those ecosystems have the protection they need to be more resilient. He points to the Hudson and James Bay Lowlands, an area five times the size of New Brunswick on the southern edge of Hudson Bay. On a map of the richest areas of carbon storage in Canada, the Hudson and James Bay Lowlands is clearly outlined in the deepest possible shade.

“That’s an area that’s accumulated carbon over thousands of years,” Snider says. “How do we avoid that becoming future emissions?”

Canada is home to the world’s largest peatland carbon stores, with peatlands covering about 12 per cent of Canada’s total land area. The area is also mineral rich and being eyed for future mining projects.

A big part of the protection required for Canada’s carbon-rich landscapes is likely to come from Indigenous protected and conserved areas, something the Cree Nation is working toward establishing.

To date, the nation has protected 15 per cent of its territory in northern Quebec, which is home to vast tracts of boreal forest, and is seeking to reach 30 per cent. Such big protected areas create resilience by having interconnected systems that protect one another.

Looking for opportunities to work with communities on the landscapes they already inhabit is key to coming up with practical, workable nature-based climate solutions, Graham Saul, executive director of Nature Canada, said in a webinar months after the Ottawa conference.

“We can ground people who care about climate change in their own landscapes,” he says, adding that efforts to build buffers against climate change can actually restore people’s relationship to the land.

This has become all the more important in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic devastation, Saul says.

A poll, released Tuesday and conducted by Pollara Strategic Insights for the International Boreal Conservation Campaign, found 70 per cent of 3,019 respondents across Canada want to see conservation of nature included as part of the economic recovery. The poll also found 72 per cent of respondents believe the government should invest in Indigenous stewardship as part of the economic recovery.

Inspired by the Great Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps in the U.S., some are asking for the establishment of a corps of workers dedicated to nature-based climate projects as part of federally funded relief programs.

Others are calling for Indigenous-led conservation efforts to be recognized as part of coronavirus resilience and recovery efforts.

“How do we ensure that nature is part of the recovery process?” Saul asks.

In the coming weeks, The Narwhal will look at the role of Canada’s natural landscapes in the fight against climate change. This Carbon Cache series is funded by Metcalf Foundation. As per The Narwhal’s editorial independence policy, the foundation has no editorial input into the articles.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits