Bill 5: a guide to Ontario’s spring 2025 development and mining legislation

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

Despite the federal government’s commitment to exceed its 2030 climate targets, British Columbians say it’s not doing enough to tackle the climate crisis.

A new survey found that 41 per cent of British Columbians think the federal government is not paying enough attention to the environment. And when asked about 10 specific environmental issues, at least three in five British Columbians said they are personally concerned about five of them: the pollution of rivers, lakes and reservoirs; air pollution; the pollution of drinking water; climate change and the contamination of soil and water by toxic waste.

“The federal government absolutely needs to do more,” Nikki Skuce, director of Smithers-based Northern Confluence, told The Narwhal. “British Columbians really care about water, particularly those of us who live close to some of these freshwater systems in places where salmon are an integral part of the culture and communities.”

Mario Canseco, president of Research Co., the company that conducted the survey, said a key takeaway from the poll is how climate change is becoming a more front-of-mind issue, with 63 per cent of British Columbians saying it’s a personal concern.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau makes an announcement in June 2019. According to a new survey, 41 per cent of British Columbians think the Liberal government is not paying enough attention to the environment. Photo: Adam Scotti / Prime Minister’s Office

“We usually see the problems that can have an immediate impact in our lives getting a higher rating,” he said, adding that issues that are perceived as not affecting us yet, such as deforestation and overfishing, typically get a lower rating. “But now we have global warming at a level that is similar to what we see for pollution.”

Around 65 per cent of respondents said they were personally concerned about the pollution of rivers, lakes, reservoirs and drinking water, and 60 per cent said they were concerned about the contamination of soil and water by toxic waste. In northern B.C., where many of the province’s industrial projects take place, those numbers were even higher, with at least 80 per cent of people saying they’re concerned about water pollution and toxic waste.

“When you live near it, you want to protect it,” Skuce said. “We need to do a better job of taking care of our rivers and lakes and creeks because they really are the veins that travel through this region.”

It’s no surprise that British Columbians — and particularly northern British Columbians — care about water and the effects of industrial contamination. In 2014, B.C. made international headlines when the tailings dam at the Mount Polley mine in the central interior broke and spilled 24 million cubic metres of contaminated waste into the surrounding water systems. Since the disaster, the provincial government has done little to improve the laws and regulations to prevent similar disasters.

Mount Polley mine’s tailings pond and tailings pile. Production was ramped up at the Mount Polley mine before a tailings pond breached in 2014, causing one of B.C.’s worst environmental disasters. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Skuce said the federal government’s role in protecting water lies in legislation and policies that guide provincial decisions on resource extraction and development.

Last year, the federal government modernized its Fisheries Act to strengthen protection of fish habitat and support restoration work, including rebuilding depleted fish populations. This follows a previous commitment to protect Pacific salmon through the wild salmon policy, which was developed in 2005 to address declining salmon populations. But according to Skuce, the federal government has yet to fully implement the policy and subpopulations of species like sockeye are on the brink of extinction throughout the province.

“As somebody who works on salmon conservation, I think it’s really important that the federal government actually steps up and implements the Fisheries Act that it updated last year and follows through on a bunch of its commitments to restore and protect habitat,” she said. “And within that, there’s the outstanding commitment to implement the wild salmon policy.”

In 2019, the federal government modernized its Fisheries Act to rebuild depleted fish populations, such as sockeye salmon, pictured here. However, according to Nikki Skuce, director of Smithers-based Northern Confluence, the government has yet to fully implement the policy. Photo: J Armstrong / University of Washington

Aaron Hill, executive director of Watershed Watch Salmon Society, said the Fisheries Act can help address the concerns of British Columbians reflected in the survey, but it has to actually be followed. “We need both levels of government to step up and, at the very minimum, fully implement the laws and policies that they already have on the books.”

He also said the BC NDP’s commitment to develop a water security strategy, which would protect watersheds throughout the province, will require collaboration and buy-in from the federal government. “It’s really important that the prime minister and Premier Horgan support that work.”

Skuce agreed and added that protecting water from pollution also requires legal reforms at both the provincial and federal levels. Despite federal mandates to protect salmon habitat, for example, provincial laws permit mining activity in salmon watersheds.

“There’s a need to enforce our existing laws and close some loopholes on some of them,” said Skuce.

The poll was conducted just after last month’s provincial election and respondents were asked how they voted. Nearly three-quarters of voters who supported the BC Greens or the BC NDP said climate change was a personal concern, but for BC Liberal voters, it was about half.

“If you take a couple of Liberal party voters, one of them is going to say, ‘Oh, I don’t care about global warming.’ That’s pretty shocking,” Canseco said.

He found that divide particularly interesting because it was the Liberal government that created the provincial carbon tax in 2008.

More than a third of British Columbians surveyed, and more than half of northern British Columbians, believe the introduction of the carbon tax has made people more mindful of their carbon consumption and led to a change in behaviour. Photo: Deb Rousseau

“It’s been 12 years that we’ve had the tax and now you have the BC Liberal voter becoming decidedly less environmentally friendly,” he said. “It’s definitely something that is troublesome. I think they’ve been moving too far to the side of industry in many ways and forgetting that this is about the future of the planet as a whole.”

More than a third of British Columbians surveyed believe the introduction of the carbon tax has made people more mindful of their carbon consumption and led them to change their behaviour, a proportion that rose to more than half of respondents from northern B.C. Almost two-thirds of British Columbians said the tax has not negatively impacted their finances.

For Skuce, government action on climate change means more than implementing carbon taxes and protecting watersheds.

“We need to stop subsidizing pipelines and fossil fuels at both the federal and provincial level,” she said.

When asked how they felt about the provincial government, 35 per cent of British Columbians said they thought the province was not focusing as much it should on environmental issues and 38 per cent said their municipal governments also weren’t doing enough.

“British Columbians perceive their municipal and provincial governments in a more positive light than Ottawa, especially with all of the commitments that have been announced,” Canseco said, referring to the NDP election promises to strengthen environmental protections in B.C. “We’ll have to wait and see if they get a better rating in the future, and also if the B.C. government keeps this seemingly high rating now that the Greens are no longer as influential in their policies.”

Hill and Skuce said given British Columbians’ concerns about water pollution, the NDP’s promise to create a water security strategy likely contributed to the public perception that the province is doing more than the federal government to protect the environment.

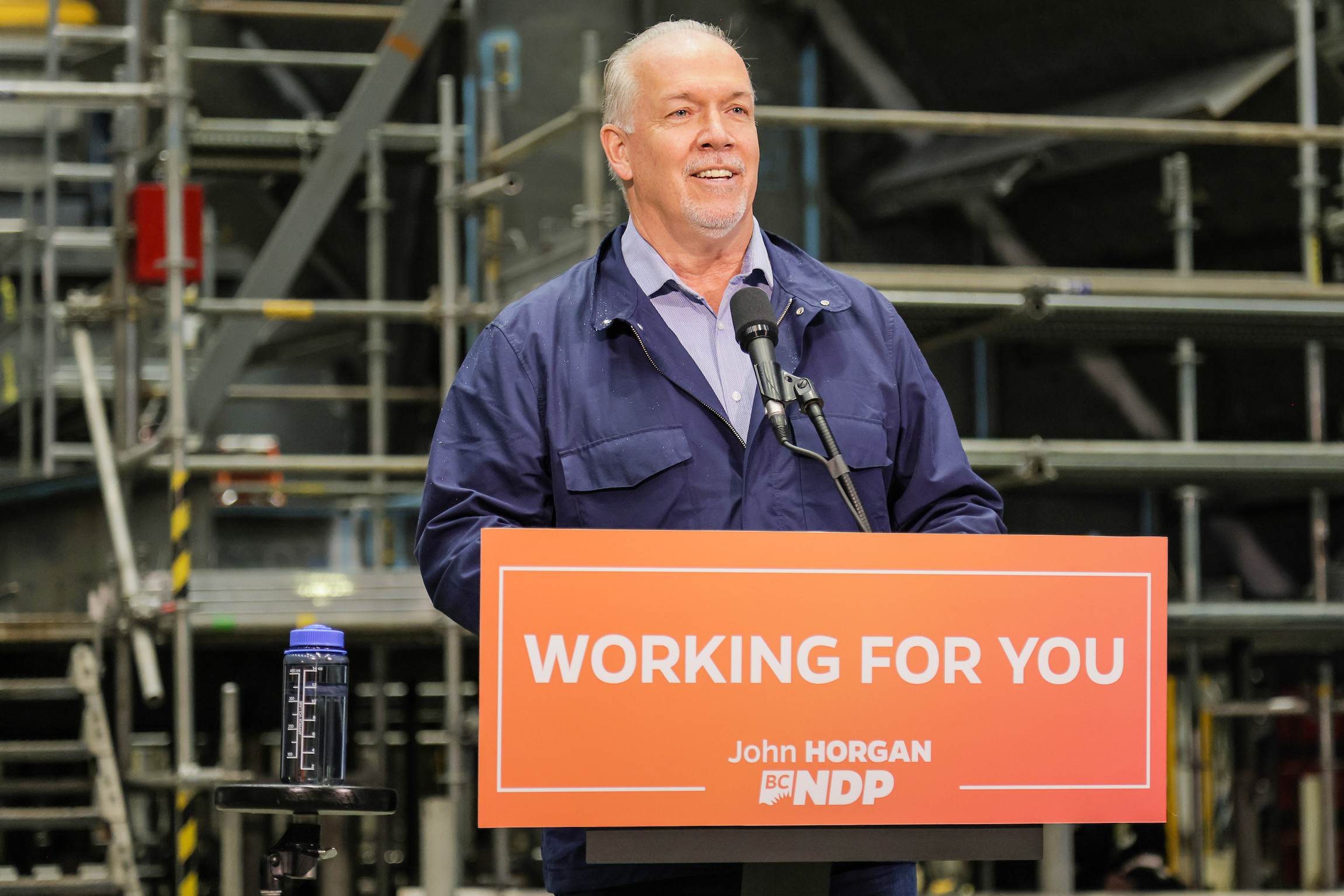

When asked about the provincial government, led by Premier John Horgan, 35 per cent of British Columbians said they thought the province was not focusing as much as it should on environmental issues. Photo: BC NDP / Flickr

But both conservationists said this perception may be somewhat skewed in part due to a lack of education. Skuce called it “jurisdictional illiteracy.”

“For instance, the federal government has committed to increasing protected areas of land and water to 30 per cent by 2030, and the Government of British Columbia has been reluctant to support that,” she said, pointing out that the province failed to meet its 2020 targets of protecting 17 per cent of land and 10 per cent of marine areas.

Similarly, the federal government has clearly defined legislation on species at risk, but as The Narwhal reported last year, B.C. still hasn’t enacted provincial legislation to protect threatened and endangered species like caribou.

Hill said governments at all levels need to step up and start working harder, collaboratively, to address the concerns of the public.

“Even though water licensing and specific on-the-ground management of water falls to provincial and local governments, the federal government approves things that affect water like pipelines and hydropower projects and they have a lot of regulatory authority as well,” he said.

Skuce said one of the ways the federal government could strengthen its commitment to protect the environment is by updating the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, which regulates the use of toxic substances and is meant to prevent pollution and protect the environment and human health. The act was legislated in 1999 and has had minor amendments over the years.

Early this year, the environmental watchdog Ecojustice called on the Trudeau government to overhaul the act to reflect current science and “reduce our exposure to pollution and toxic chemicals.”

Skuce said the act could provide the federal government with the “tools to help protect our watersheds through environmental and climate action.”

The federal government has released new legally binding legislation that commits Canada to reaching net-zero emissions by 2050. Photo: Justin Trudeau / Flickr

Hill said the federal government made significant commitments to environmental protection last year when it promised to create a new Canada Water Agency in its mandate letter to the minister of Environment and Climate Change Canada. The letter also promised to strengthen the Canadian Environmental Protection Act and introduce new greenhouse gas emissions reduction programs. Earlier this month, the Trudeau government introduced a bill to support its goal of reaching net-zero emissions by 2050. The legislation would require the minister of environment to set five-year emissions reduction targets starting in 2030, along with a plan for meeting those targets.

Hill said that in addition to the commitment to create a Canada Water Agency, governments already have the means to strengthen environmental protection.

“The premier and the prime minister [need] to give their cabinet ministers and their staff a clear mandate and adequate resources to actually do their jobs and implement the laws that are already on the books,” he said. “Whether it’s mining or fracking or clear-cut logging or extraction of water for various purposes, there’s a whole lot of room for improvement. And people are right to expect that the government will do better.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy