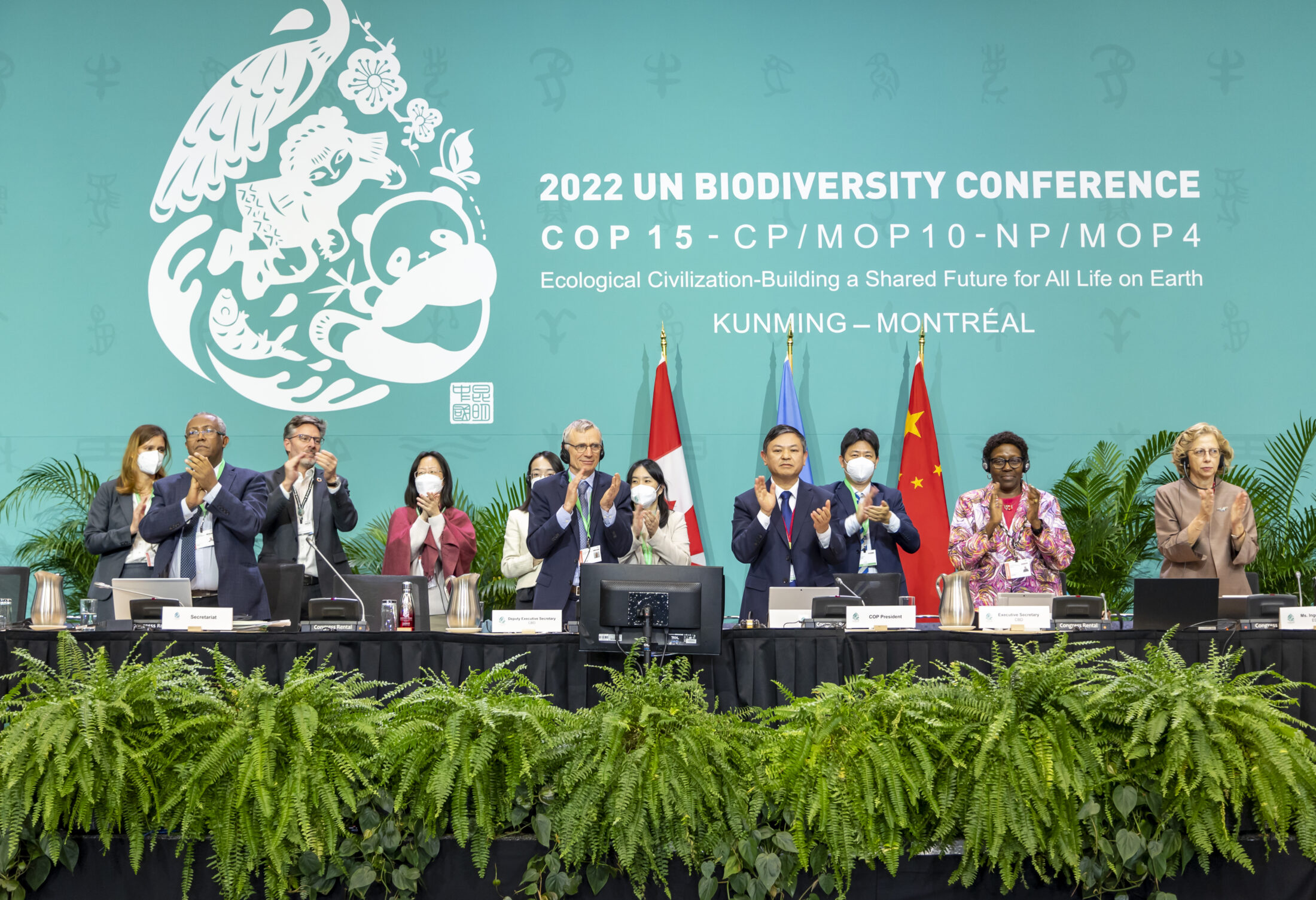

After some tense moments, including a brief breakdown in talks, 196 countries reached a new global agreement at COP15 to stem the stunning loss of biodiversity worldwide.

Though not quite as ambitious as many hoped it would be, the new Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework lays out a series of 23 targets that — if met — could help prevent further extinctions.

Among the targets, countries agreed to ensure at least 30 per cent of the world’s land and waters are effectively conserved and managed by 2030, to significantly reduce the risk of extinction, to phase out or reform at least $500 billion in subsidies that harm biodiversity and to reduce the risks from pesticides and other harmful chemicals by at least half.

“The health of our forests, oceans, animals and all biodiversity underpins the very strength and stability of our societies. We cannot take that for granted any longer,” Environment and Climate Change Canada Minister Steven Guilbeault said in a statement Dec. 19 from COP15, the United Nations biodiversity summit held in Montreal during the last two weeks.

“Here in Montreal, we have set a new course. Now it is time to deliver,” he said.

“This agreement is a critical achievement and if implemented fully could take great strides towards combatting extinction and conserving biodiversity,” Charlotte Dawe, a policy and conservation campaigner with Wilderness Committee, said in a statement Monday.

She warned, however, “there is much more work to be done and governments must use policy change to achieve the targets.”

“Currently, businesses are trusted to ‘do the right thing’ when it comes to nature protection, and they fail every time,” Dawe said.

The question now is whether governments will take the necessary action to meet the targets they’ve adopted. Their track record so far is poor.

Countries failed to fully achieve any of the targets adopted in 2010 under the previous agreement.

And in the 30 years since the first countries signed onto the international biodiversity treaty, under which these 10-year agreements are negotiated, the state of nature has declined dramatically.

Today, biodiversity is shrinking faster than at any other point in human history. Numerous species have already been erased from the planet and one million more are at risk of extinction.

Canada made big conservation commitments at COP15, but big promises have been made before

In Canada, more than 5,000 wild species are at some risk of extinction, according to the most comprehensive assessment of biodiversity ever undertaken here.

Guilbeault and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau signalled a renewed commitment to the conservation of biodiversity with a flurry of announcements at COP15.

They committed $800 million over seven years to four Indigenous-led conservation initiatives, announced support for the First Nations Guardians Network, next steps towards the creation of two significant Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas and committed millions of dollars for ocean restoration projects. The first in a series of bilateral nature agreements between the federal and provincial and territorial governments was also announced between Canada and the Yukon. The long awaited agreement with B.C. is expected in the New Year.

Throughout the conference, Canada pushed countries to formally adopt the 30 per cent protection by 2030 target (commonly referred to as 30 by 30) at COP15, positioning it as a sort of north star for biodiversity in the same way that limiting warming to 1.5 C is for climate change.

Trudeau told reporters during a roundtable discussion he was optimistic Canada had a clear path to conserving 25 per cent of lands and waters by 2025 on its way to meeting the 30 by 30 goal. (Canada had conserved 13.5 per cent of lands and freshwater as of the end of last year and 14.66 per cent of marine areas as of June.)

At the same time, the federal government committed to a major shift in the way conservation and land use decisions are made to one that ensures Indigenous nations are in the “driver’s seat.”

“They’re saying everything we want to hear, but there’s a little bit of a ‘well, let’s just see,’ because the track record — it’s not a great track record,” Clarissa Sampson, an ecological economist at the David Suzuki Foundation, told The Narwhal.

In B.C. — the province with the highest number of species at risk — Premier David Eby recently directed his new minister of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship, Nathan Cullen, to work towards protecting 30 per cent of B.C.’s lands by 2030, which will be critical to meeting Canada’s international targets because the province has currently only protected about 15 per cent of land.

In a sit-down interview with The Narwhal at COP15, B.C. Energy, Mines and Low Carbon Innovation Minister Josie Osborne and Environment and Climate Change Strategy Minister George Heyman said the province is also changing the way land use decisions get made.

Heyman noted the province has committed to implementing the recommendations from a 2020 review of the way it manages old-growth forests. A key recommendation was to shift away from an industry-first approach to one that prioritizes ecosystem health and determines from there how economic activity fits in, he said.

“To me, it’s a matter of understanding that both environmental and ecosystem health and economic activity are interdependent,” Heyman said.

Osborne added that the creation of the Ministry of Water, Land and Stewardship was a significant step as it brought land-use planning and natural resource policy-making under one roof so to speak.

“That really is a recognition of the Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act and the fact that we must do business differently in the province,” she said.

Osborne said B.C. is shifting its approach to conservation away from the “hard edges” of parks and other protected areas, echoing comments Trudeau made earlier this month about leaving a parks-style approach to conservation behind.

Instead, the province is looking at ways to preserve “the ecosystem services that we all rely on, but at the same time, allow for certain activities done in the right place in the right way by the right people,” Osborne said.

Conservation groups worry B.C. may rely on ‘fancy’ accounting to meet goals

Internal government documents obtained by The Narwhal suggest B.C. plans to rely on old-growth management areas, ungulate winter range designations and wildlife habitat areas — which do not ensure long term protection — to meet its conservation goals.

Dawe worries the approach is “a fancy way of basically hitting those 30 by 30 targets on paper.”

“In actuality there’s no way you can log a forest and call it protected,” she said.

“Anyone now that goes for a drive in a forested area or a mountainous area will see scars, cutblock scars across the land, so I think this green idea of B.C. is really starting to crack and break,” Dawe said.

Old-growth forests hold an immense amount of biodiversity. When they’re destroyed, so is their ability to support plants and animals, including endangered caribou and spotted owls. Their loss is also felt deeply by communities.

“Since I’ve been in Montreal at COP15 they’re going full bore deforesting my ancient lands. And I don’t know what to say, it’s disheartening,” Kwakiutl Hereditary Chief Walas Namugwis, whose English name is David Mungo Knox, told The Narwhal.

“We’re not us without our old-growth trees, we can’t make our totem poles, we can’t carve our big houses, we can’t carve canoes, without our medicines we can’t heal. So it’s another cultural genocide,” he said, at a hotel restaurant across the street from Montreal’s Palais des Congrès where negotiations were underway.

Back in his home territory on Vancouver Island, trees were being cut down near where coho salmon had recently spawned and in the habitat of the northern red-legged frog, a species of special concern under the federal Species at Risk Act.

“Governments need to grow a spine, push back against big corporate industrial market approaches and then let a more diverse economy flourish,” Mark Worthing, director of Awi’nakola Foundation, a new organization that combines Indigenous Kknowledge, scientific research and the arts to conserve and restore forests.

“We’ve lost the taste for announcements,” he said. “Stop talking about it, start doing it.”

“That’s pretty much been my take home from this too. We need radical change and that needs to come now,” Ma’amtagila Hereditary Chief Makwala, whose English name is Rande Cook, said.

“We’re in a place right now where it literally is about the planet and we’re putting a timeline on the existence of humanity. For the health of all of us we need to make some real radical changes,” Cook, who is also part of the Awi’nakola Foundation, said.

Asked at what point the B.C. government would, for instance, issue a hard stop of logging in critical caribou habitat, Osborne noted the “importance of land use planning with Indigenous nations and really truly listening.”

“So incorporating those worldviews, those values and understanding what the solutions are we can provide together so that we know and we agree together enough is enough,” she said.

Osborne added that it’s also important to understand decisions around resource and land use impact communities.

“Simply stopping an activity overnight isn’t going to provide the kind of assistance or security or ability for a community to determine what its next steps are, how people are going to continue to support themselves and their communities and that has to be part of this conversation as well,” she said.