Hope for a huge, ancient and imperilled fish

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

Bob Chamberlin is in a long-term relationship with wild Pacific salmon.

“My relationship with fish and salmon began pretty much when my life did,” said Chamberlin, who is a member of the Kwikwasut’inuxw Haxwa’mis First Nation in the Broughton Archipelago and chair of the First Nations Wild Salmon Alliance.

“I was raised with salmon.”

Chamberlin reminisces on the joy he felt after he fed his family with cod he had caught when he was just seven years old. He later went on to become a commercial fisherman based out of Campbell River, during which he continued providing his family with fish, and especially salmon, a traditional food.

For many First Nations communities in B.C., Pacific salmon represent “so much more than a menu choice,” said Chamberlin, citing how salmon sustain survival and existence for many Indigenous communities on the coast and along river headwaters.

He’s fighting to protect wild Pacific salmon, which are already facing devastating population declines along the coast. And he’s particularly concerned about open-net pen fish farms in coastal waters.

In 2019, the federal government vowed to phase out open-net pen fish farms by 2025, but later walked back on its pledge by re-wording their timeline to simply have a plan developed by 2025 to make the transition away from open-net pens.

In late July, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) quietly released a report on the findings of its initial engagement process with stakeholders, but did not include any update on its plan or timeline to phase out open-net pens from B.C. waters, sounding alarm bells for conservation groups who say protecting wild salmon requires immediate action.

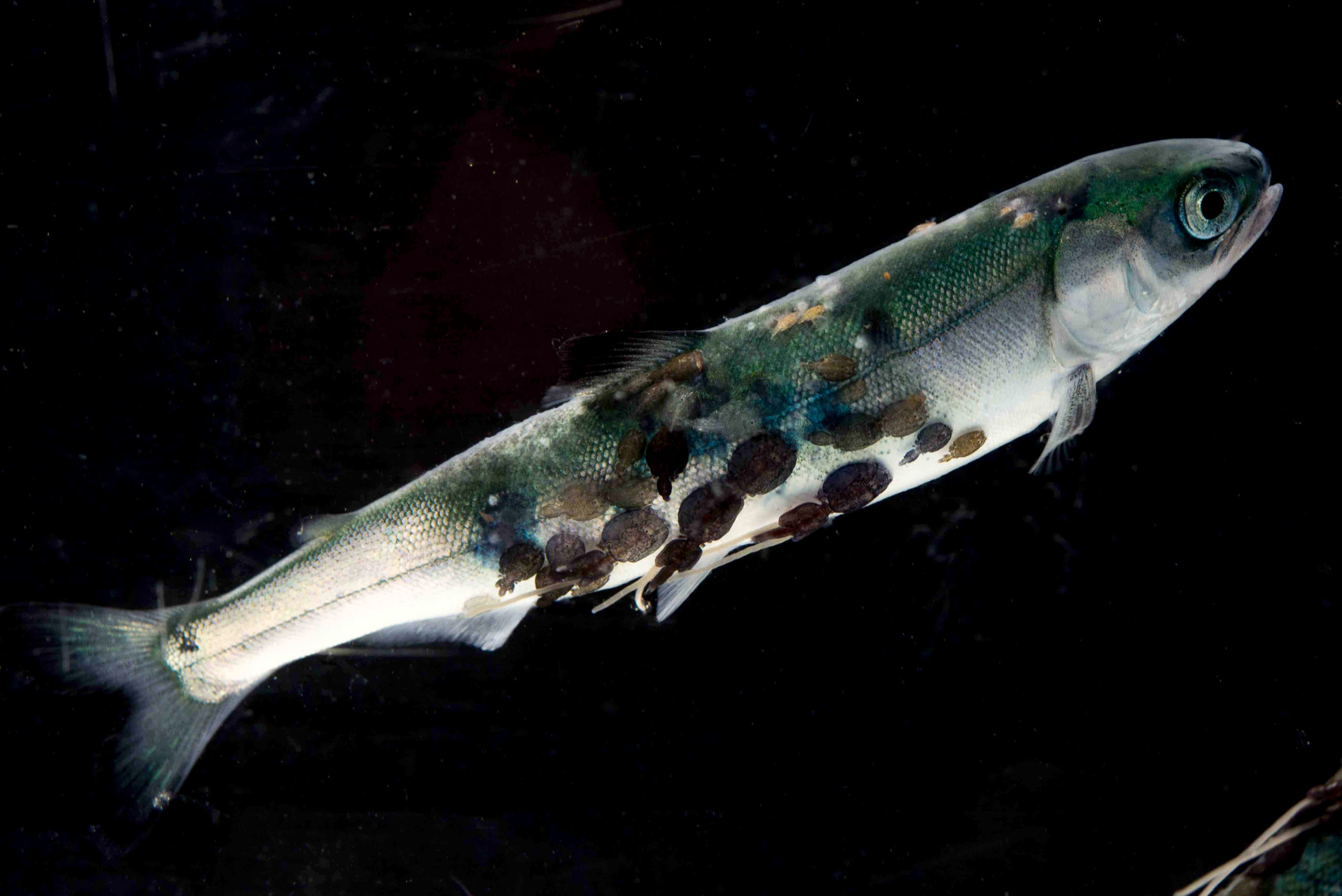

Open-net pens can release sea lice, disease, excess food and feces into the marine environment and increase the risks of harmful algal blooms and diseases for wild fish, with elevated risk along migratory pathways for wild salmon. When Atlantic salmon are farmed in open-containment systems in Pacific waters, mass escapes could affect wild Pacific salmon.

“We’re in a state of crisis and need that plan,” Karen Wristen, the executive director of environmental organization Living Oceans Society, told The Narwhal. “Wild salmon can’t wait.”

A new poll from Insights West reveals that 86 per cent of B.C. residents are extremely concerned about declining Pacific salmon stocks and 75 per cent believe that fish farms should be transitioned to land-based systems.

The DFO report expressed a wide range of views based on input from First Nations representatives, local governments, fish health experts and researchers, environmental groups and the fish farming industry.

The report is based on the feedback of 114 participants and over 5,400 written submissions gathered between December 2020 and April 2021. Quoted stakeholders are unnamed throughout the report.

Participants suggested various alternatives to open-net pen fish farming, such as land-based aquaculture, closed- or semi-closed containment systems, and hybrid methods, which involve moving fish from land to the ocean during different life stages.

Wild fish advocates say hybrid systems won’t solve the issues with open-net pens. “That’s no improvement,” Wristen said.

While the report did not include a fish farm transition timeline nor a plan to support affected communities with economic opportunities, it did acknowledge the time sensitivity in upcoming renewal options for B.C.’s 109 federally-issued fish farm licences — the majority of which are set to expire next year.

“A large percentage of tenure decisions will need to be made by June 2022 — an important milestone for this transition. The decisions made during this transition will have a significant impact on the livelihoods of British Columbians,” wrote MP Terry Beech, parliamentary secretary to the minister of fisheries, in the report’s foreword.

This acknowledgement signals hope for those campaigning to phase out open-net pens, who say they believe their work is being heard by decision makers.

Wristen recommends DFO consider alternatives to renewing those licenses, noting tenures could be turned over to First Nations communities who want to pursue some form of aquaculture. Shellfish or seaweed farming, forms of restorative aquaculture that benefit marine ecosystems, should be considered as alternatives, she said.

By 2025, Wristen hopes the open-net pens are, once and for all, out of the water.

“The farming of fish is no doubt an important part of our future, but it needs to be done on land in controlled conditions so it doesn’t pollute the environment.”

In the new DFO report, some participants questioned the department’s oversight, echoing concerns that have been raised for nearly a decade.

“Rebuilding wild fish stocks should not be tied to the evolution of the aquaculture industry — it should be a separate initiative,” said one stakeholder in the report.

The idea that DFO’s mandate represents potential conflict of interest — both conserving wild fish while promoting the interests of the aquaculture industry — dates back to 2009, when Canada established the Cohen Commission to investigate the decline of sockeye salmon populations.

The commission released their final report in 2012, coupled with 75 recommendations. One recommendation called on DFO to eliminate its promotion of the aquaculture industry.

“The problems associated with aquaculture are substantially exacerbated by DFO’s stated mandate to promote the aquaculture industry, and its movement away from simply conserving wild fish,” reads the 2012 report.

While DFO said it has acted on all 75 recommendations of the Cohen report, conservationists say several recommendations under the aquaculture umbrella still await implementation.

For instance, the Cohen Commission report recommended removing all open-net pens from B.C. waters. The federal government recently announced that 19 open-net fish farms along a key migration route in the Discovery Islands near Campbell River, B.C. will be phased out by June 30, 2022.

When pressed on the question of a timeline for removing the remaining farms, a spokesperson for the DFO told The Narwhal, “the Government of Canada is committed to working with relevant partners and stakeholders on the development of a responsible plan for transitioning open-net pens in coastal B.C. waters by 2025.”

The 2012 Cohen report also recommended applying the precautionary principle to B.C.’s aquaculture management, which means that conservation measures should be applied when scientific certainty is not confirmed and when there is a risk of serious or irreversible harm to the environment.

Several stakeholders who participated in DFO’s initial engagement report advanced the same recommendation. “The precautionary approach is the only approach for B.C.,” wrote one participant who believes open-net pens harm wild Pacific salmon.

Achieving scientific certainty and understanding the potential ecological consequences of fish farms will require comprehensive risk assessments, which wild salmon advocates say DFO has not yet completed.

“There’s absolutely zero objectivity or credibility” in the risk research the DFO has published to date, Chamberlin, from the First Nations Wild Salmon Alliance, told The Narwhal. Last Fall, multiple First Nations leaders conveyed doubt about a DFO assessment that found fish farms pose minimal risk to declining wild sockeye salmon populations.

Other events have undermined the public’s trust in the department and its commitment to protecting and promoting the recovery of wild salmon stocks.

Recently, The Narwhal reported on internal documents that reveal DFO scientists discussed mouth rot disease that infested Atlantic salmon farms in B.C. with the salmon farming industry last fall, but without informing the public or First Nations communities about the “realistic and serious” risks of transmission to wild salmon. The DFO has also been accused of not disclosing contributions from the salmon farm industry to fund fish farm research.

The DFO report notes that “several participants suggested that there was some distrust of DFO as the organizer of an engagement process for providing input into a transition plan” away from salmon farms.

Chamberlin said DFO’s track record on science and decision-making in aquaculture has made himself and other Indigenous stakeholders wary.

“They have a really long road to go before there’s any measure of trust with First Nations,” said Chamberlin, who is currently collaborating with Indigenous communities across the province to put together a B.C. First Nations Salmon Restoration Framework.

DFO acknowledged the “ongoing lack of proper engagement with First Nations on fisheries and aquaculture” in the new initial engagement report, which devotes a section to advancing reconciliation and aligning the engagement process with principles in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

Within a section of the report addressing reconciliation, stakeholders commented on the need for nation-to-nation, government-to-government engagement for shared decision-making and for DFO to build resourcing and capacity into the process to ensure First Nations communities can participate.

Some participants shared Chamberlin’s frustration with DFO.

“We the chiefs gave the authority to DFO to manage the resources and we’ve come to the state where we’re at the last buffalo, only instead it’s the last wild salmon and the last herring,” the report quotes one participant as saying.

The formal open-net pen fish farm engagement process is scheduled to begin this fall.

In an emailed statement to The Narwhal, DFO said future engagement will build on conversations and feedback reflected in the initial engagement report, noting additional programs to support the process.

“DFO is developing a funding program that will support First Nations with support for travel, training or other activities related to consultation sessions. DFO is also working with the First Nations Fisheries Council on the development of an Indigenous engagement strategy and communication materials.”

While it’s unclear how DFO will proceed in developing a plan to phase out open-net pens and what their final approach to reconciliation and engagement will entail, Chamberlin hopes the department will put wild salmon first by phasing out open-net pens and separating its primary responsibility of wild fish conservation from its engagement with the aquaculture industry.

Above all, Chamberlin said DFO must respect how First Nations communities choose to organize themselves and must provide Indigenous stakeholders with adequate resources for capacity to participate in and inform a full-fledged transition plan.

“DFO Pacific has specifically done a very, very poor job in terms of reconciliation with First Nations. They have mountains to climb and rivers to cross to get anywhere near a measure of reconciliation on fish,” he said.

Updated Thursday, August 19, 2021 at 3:06 p.m. PT: This article was updated to remove reference to the ability of escaped farmed Atlantic salmon to disrupt the genetics of wild Pacific salmon. Atlantic and Pacific salmon cannot interbreed, so fugitive farmed salmon do not pose the genetic threat on the Pacific coast of Canada that they do on the Atlantic coast. Escaped farm Atlantic salmon do pose a threat to wild Pacific salmon stocks, however, through the transmission of disease and parasites.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. Angello Johnson’s shoulders burn, and his arms...

Continue reading

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

We’re excited to share that an investigation by The Narwhal is a finalist for the...

A new documentary, Nechako: It Will Be a Big River Again, dives into how two...