Teck Coal was ordered to pay a record $60 million fine this year for polluting waterways in the Elk Valley, but despite the penalty, contaminants continue to leach from piles of waste rock at the company’s mines — and the clock is ticking on new federal regulations that observers say are long overdue.

“Leadership is desperately needed in this watershed from the Canadian federal government,” said Erin Sexton, a University of Montana biologist.

The Elk Valley may have “one of the worst selenium contamination issues, I would say, even globally,” she said. And yet, “over the last decade and a half, there’s been a notable lack of regulatory response in this watershed to the water quality issues.”

New regulations are on the way, but there is concern they won’t be strong enough to address the legacy of pollution from more than a century of coal mining in the Elk Valley.

The coal mining operations fall within the territory of the Ktunaxa Nation, which in March called for there to be “an appropriate and achievable plan in place to ensure that Teck Coal Limited meets water quality limits and addresses impacts to wuʔu (the water) and ʔa·kxamis ̓qapi qapsin (All Living Things).”

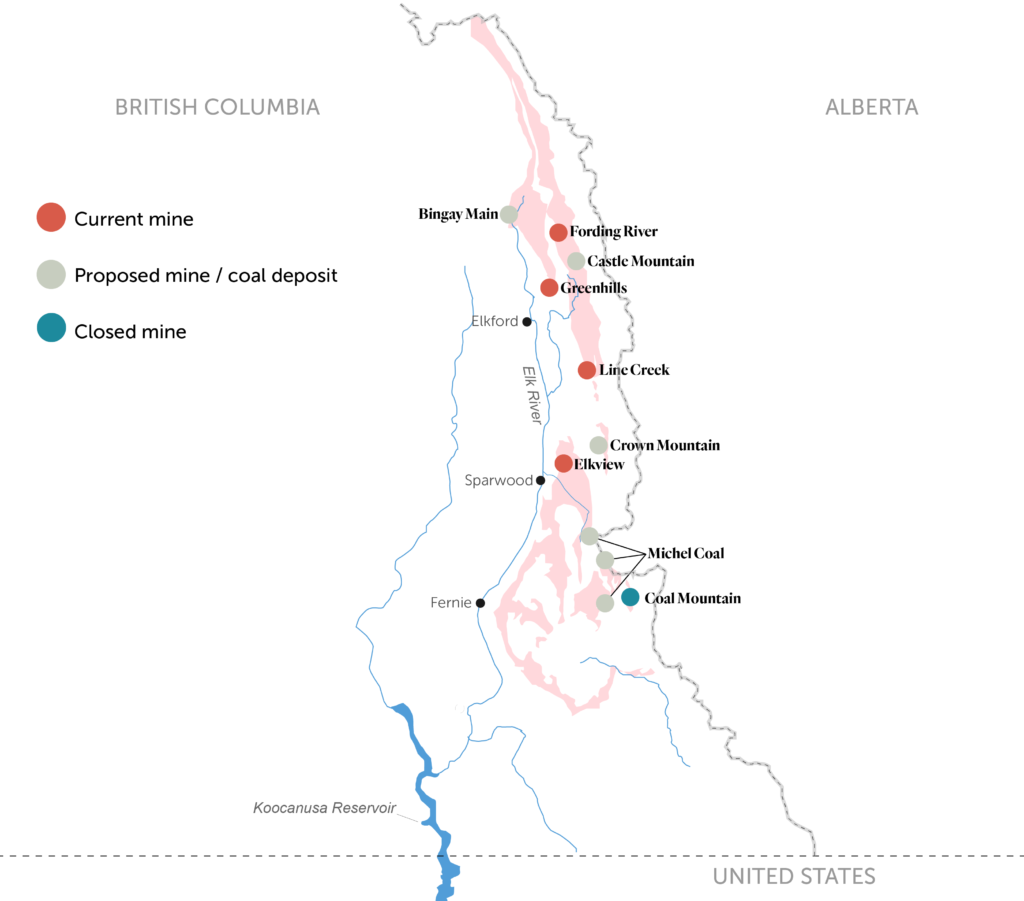

With several new coal projects proposed in the region, including a Teck mine expansion, experts say swift and strong measures are needed to ensure the region’s pollution problems don’t get worse.

If the federal government’s draft regulations are any indication, Sexton said, the changes could be “a lot too little and a lot too late.”

Her comments come in the lead up to a bilateral Canada-U.S. meeting this week focused on cross-border water issues. Transboundary mining will be on the agenda in the gathering between Global Affairs Canada, Environment and Climate Change Canada, the U.S. Department of State and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Selenium pollution a persistent challenge in the Elk Valley

Selenium, which leaches from the mines’ waste rock piles, is toxic to aquatic life at elevated levels. Species of mayflies, stoneflies, and caddisflies — food for fish — have already been lost, Sexton said. In fish, selenium poisoning can cause deformities and reproductive failure. It’s a pressing concern for the westslope cutthroat trout, which is listed as a species of concern under the Species at Risk Act.

Teck has so far invested roughly $1 billion in water treatment facilities and other measures to address water pollution in the Elk Valley. Currently, selenium is removed from up to 27.5 million litres of water a day at two treatment facilities, spokesperson Chris Stannell said in a statement to The Narwhal.

With additional treatment facilities being constructed, the company is aiming to be able to treat more than 54 million litres of water a day by the end of this year and expects to see “significant reductions in selenium and nitrate concentrations throughout the watershed as a result,” Stannell said.

Westslope cutthroat trout is listed as a species of concern under the Species at Risk Act. In fish, selenium poisoning can cause deformities and reproductive failure. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

But data from monitoring stations in both the Elk River and Lake Koocanusa, a reservoir that crosses the Canada-U.S. border, shows selenium concentrations have increased despite these efforts, according to Lars Sander-Green, a mining analyst with the Kootenay-based conservation organization Wildsight.

“More mining is more waste rock and more waste rock is more water pollution,” Sander-Green said.

“Teck is planning and has built some small treatment plants but so far they’ve been increasing mining faster than they’ve been bringing treatment into place,” he said.

At this point, Sander-Green said he estimates that Teck is able to remove about 10 per cent of the total selenium pollution that flows downstream of its mines.

Teck did not answer questions about what percentage of its mining wastewater is treated to remove selenium.

Federal oversight of coal mining ‘desperately needed’ in Elk Valley

Teck’s coal mines are subject to the Fisheries Act, which prohibits the release of a “deleterious substance” in fish-bearing water. The company’s recent $60 million fine, for example, stemmed from an investigation that found “deposits of waste rock from the company’s operations had leached deleterious substances, selenium and calcite, into the upper Fording River and its tributaries,” according to an Environment and Climate Change Canada summary of the case.

However, there’s been a longstanding gap when it comes to how coal mining is governed under the Fisheries Act because there aren’t any regulations specific to the coal industry.

“There are regulations for paper mills, for example, or metal mines, but not for coal mining,” Dan Cheater, a lawyer with Ecojustice, said.

Regulations governing effluent from metal mines have been in place for more than four decades and updated twice in the intervening years. But it wasn’t until 2017 that Environment and Climate Change Canada began working on regulations for coal mining effluent — despite its responsibility to protect fish and fish habitat under the Fisheries Act and the federal government’s commitments under the Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909 to not pollute transboundary waterways.

(Pollution from the Elk Valley coal mines has long been a source of contention between Canada and the U.S. as contaminants from Teck’s mines eventually flow into Lake Koocanusa, a reservoir that straddles the B.C.-Montana border.)

In a statement, Stannell said: “Teck supports the development of regulations that are informed by a science-based approach, protective of aquatic life, and considerate of available treatment technologies.”

Those with long-standing conservation concerns, including Sexton, welcome the prospect of new regulations.

“I am 100 per cent in support of federal oversight in this watershed, I think it’s desperately needed,” she said.

“Not only are we well beyond what’s considered protective of fish and aquatic life in this watershed, we’re actually looking at expanding those impacts with the Fording River mine expansion and the three new coal mines that are proposed in the Elk Valley.”

As for Cheater, he said he’s “hopeful that with these regulations, we’ll start seeing some progress.”

University of Montana biologist Erin Sexton takes a water sample in the Koocanusa Reservoir as part of an independent water testing program. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

Draft coal mining effluent regulations have been watered down

But there is reason to be wary.

“One thing that we’ve seen as new materials are being released by the federal government is there is a watering down of what the regulations were originally set to do that I think is disappointing,” Cheater said.

Initially, Cheater said, the proposal included the ability to adjust contaminant limits based on fish health and concentrations in fish tissue samples. That was subsequently changed to a “strict limit” that applied to new mines and expansions.

“Now we’re seeing an exception carved out for the Elk Valley specifically,” he said.

Sander-Green called it “a Teck-sized hole in the regulations — there’s a whole set of regulations, that’s just for Teck, that’s much, much weaker, allows a lot more pollution than it would for a mine in Alberta or Nova Scotia.”

An Environment and Climate Change technical briefing document from February 2020 shows the federal department proposed a “two-pronged approach” to the regulations: a general approach that applies to new and existing mines and an alternative approach that applies only to the existing coal mines in the Elk Valley.

The draft general regulations as proposed early last year would apply limits to the concentrations of selenium, nitrate and suspended solids in mine effluent from final discharge points, with slightly weaker standards for existing mines.

Selenium levels by the numbers

Regulations for selenium pollution vary widely in the U.S. and Canada. Teck has been given plenty of latitude by the B.C. government to exceed provincial standards, prompting observers to call for stringent new federal rules.

0.8

The parts per billion limit recently adopted by U.S. agencies for Lake Koocanusa, where average selenium levels are about one part per billion.

2

B.C.’s general water quality guidelines currently recommend selenium levels be kept within two parts per billion to protect aquatic life.

63

Teck’s provincial permit allows selenium levels in rivers and creeks downstream of the company’s mines to far exceed the provincial water quality guideline. For instance, one of its Fording River order stations has a limit of 63 parts per billion.

Provincial regulations not enough to protect fish from coal mine pollution

Teck’s coal mines are already regulated by a provincial permit, which sets limits on how much of a contaminant, such as selenium, the mines can release into the environment — but Sander-Green said the limits are too high and Teck has too often failed to meet them.

For example, B.C. government inspection records for one of Teck’s Fording River order stations, where water quality is regularly monitored, show average selenium levels in March 2020 measured 65.7 parts per billion and averaged 67.9 parts per billion in December. That’s higher than the allowable permit threshold of 63 parts per billion.

The company is also required to ensure selenium concentrations at one of its Fording River compliance points, where mine effluent is monitored, do not exceed a monthly average of 90 parts per billion. But inspection records show average selenium concentrations were 112 parts per billion in October 2020, 102.5 parts per billion in November, and 124 parts per billion in December.

The company could face new administrative penalties from the province for failing to meet the requirements of its permit, but according to Stannell those exceedances were unusual occurrences.

“In 2020, water quality at order stations met permit limits 99 per cent of the time and at compliance points 93 per cent of the time,” he said. “We expect to further improve on this performance as additional water treatment comes online this year.”

An aerial view of a Rocky Mountain coal mine in B.C.’s Elk Valley near the B.C.-Alberta border. Photo: Callum Gunn

Observers say draft federal regulations aren’t strong enough to address Elk Valley pollution woes

Under the draft federal regulations, Teck’s existing mines would be required to meet baseline pollution limits set two and three years after the regulations are enacted. The company would then be required to reduce concentrations of selenium in the environment relative to that baseline in subsequent years.

For instance, based on the February 2020 draft, the company would have to reduce monthly average selenium concentrations at federal compliance points by 36 per cent from the baseline, or to 40 parts per billion, whichever is lower, 16 years after the regulations are enacted.

Existing mines subject to the general regulations, meanwhile, would be required to meet a monthly average selenium limit of 10 parts per billion for effluent that is collected and released at specific outflow locations. New mines would face a limit of 5 parts per billion.

Four companies are proposing new coal mines in the Kootenay Rockies. Conservationists fear increased pollution in the region if they are approved. Map: Carol Linnitt

Sander-Green worries that “the proposed regulations would create a perverse incentive for Teck to do less to control their pollution in the coming years.”

“It’s actually in Teck’s interest to keep pollution levels as high as possible until three years after these regulations come into force, because their pollution limits for the rest of the life of the mine would be based on pollution levels in the years after the regulations come into force,” he explained in an email to The Narwhal.

While the February 2020 draft regulations would eventually set a minimum requirement that monthly selenium averages don’t exceed 40 parts per billion, Sexton noted that’s still 20 times higher than the selenium concentration that’s considered protective of aquatic life.

In a statement to The Narwhal, Samantha Bayard, a spokesperson for Environment and Climate Change Canada said “the proposed regulatory rules for existing coal mines in B.C.’s Elk Valley take into account the unique circumstances in the region.”

Coal mining in the area has “resulted in vast mine waste rock piles that often overprint water bodies, which make it impractical for existing mines to collect all of the mine effluent and apply the same effluent quality standards that can be achieved by newer facilities,” she said.

But Sexton argued the existing Elk Valley mines “should be held to the highest standard because according to the science this is the watershed that’s most at risk.”

Experts are increasingly worried by the high levels of selenium found in rivers near B.C.’s scenic Elk Valley, which is a great risk to aquatic life. The province has yet to finalize specific selenium pollution limits. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

At this point, selenium levels in the Elk and Fording rivers are “orders of magnitude” higher than what is safe for fish and other aquatic life, she said.

The Narwhal asked Environment and Climate Change Canada when the regulations would be finalized. In a statement, Bayard said that “given the importance of these regulations, we are taking the time to get them right. This will include extensive consultations with industry, Indigenous groups, environmental non-governmental organizations, and provinces.”

The timeline is a concern for Sander-Green, who noted any new coal mines built in the next few years may only be subject to the weaker standards for existing mines. According to the February 2020 technical briefing document, the draft regulations define new mines as mines that start operating three years after the regulations are enacted.

Sander-Green said any further delay is unreasonable. “There’s no reason we shouldn’t have had these regulations in place years ago,” he said.

‘Short-term solutions to long-term problems’

Even with new regulations forthcoming, there are concerns on both sides of the Canada-U.S. border about the long-term implications of continued coal mining in the Elk Valley.

While Teck is making considerable investments in water treatment, Sander-Green is concerned it won’t be a viable solution over the course of the decades or centuries to come.

“What these regulations should be doing is banning perpetual water treatment and prohibiting mines that will leave behind toxic pollution problems that will last beyond the lifetime of the mine,” he said.

It’s a concern Sexton — who called the water treatment facilities “short-term solutions to very, very long-term problems”— shares.

Robert Sisson, a U.S. commissioner on the International Joint Commission (IJC), recognizes the major investments Teck has made in water treatment facilities, including saturated rock fill technology.

But “I’d like to make sure that we’re also discussing Plan B and Plan C, in the event [the saturated rock fill technology] does not work as intended or it’s just simply not enough to do the job that we need to protect the waters,” he told The Narwhal in an interview.

Sisson said a bi-national watershed body that brings all interested groups and experts together could be helpful for finding a solution to the long-term pollution challenges in the Elk Valley.

“The IJC would be a good option, but there are others out there,” he said.

Under the Boundary Waters Treaty, the International Joint Commission has the power to investigate and recommend solutions to transboundary water disputes referred to it by the U.S. and Canadian governments.

The commission has alerted both governments to the selenium issues in the Elk Valley watershed, but has so far not been asked to intervene in the situation.

In the meantime, selenium and other contaminants continue to leach from piles of waste rock at the mines.

With new projects and mine expansions being proposed, Sexton said she wants to see a moratorium on any new or expanded mines in the Elk Valley until the existing pollution problems are addressed.

“We have clear evidence now that this watershed is in trouble,” she said. So, “the first thing you do is try to stop the bleeding.”