In a Nova Scotia research lab, the last hope for an ancient fish species

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...

Teck’s Castle Mountain expansion project in B.C.’s Elk Valley looks, at first glance, a lot like a new mine.

But the company describes the proposed project as a mere extension of Teck’s current Fording River mine (the biggest coal mine in B.C.) — a distinction that means the proposed Castle Mountain project does not automatically qualify for a federal impact assessment.

Yet critics say Teck’s plans require the leveling of another mountain, the destruction of wildlife habitat and the increase of dangerous selenium pollution in the Elk Valley’s waterways.

The expansion is currently submitted for an initial project review with the B.C. Environmental Assessment Office only, but in May the leadership of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho formally asked Ottawa to submit the project to a robust federal review.

Canada has 90 days to decide whether or not the project — quibbles about it being an ‘expansion’ or a ‘new mine’ aside — will undergo a review with the Impact Assessment Agency.

Here’s what we know about Castle Mountain — and its potential environmental impact.

Teck’s “current understanding” is that the Castle Mountain expansion does not constitute a new mine, even though the company admits the expansion project’s future annual output of coal would be the same as the Fording River mine’s current output of 10 megatonnes of steelmaking coal a year. (One megatonne is the equivalent of one million metric tonnes, in case you were wondering.)

Teck also designates the project as an expansion even though new coal pits would be constructed entirely outside the current permitted area for the Fording River.

Teck argues Castle — in spite of being a set of new pits, at a new site, outside of the currently permitted mining area — will be part of Fording River operations because it will make use of “existing FRO access roads and power lines” and “coal processing plant facilities,” as well as offices, warehouses, and equipment.

The company does acknowledge Fording River’s current supply of economically usable coal will be exhausted by the early 2030s, and that the Castle pits would become the sole source of coal for the operation from then on.

In the eyes of regulators, whether a mine is “new” or an “expansion” depends not only on its level of production, but also, if it’s adjacent to a pre-existing mine or its size relative to that mine.

Essentially, the Physical Activities Regulation requires a federal assessment only for coal mine expansions that “result in an increase in the area of mining operations of 50 per cent or more” and in which daily total coal production after the expansion would stand at 5,000 tonnes or more.

Teck says Castle would maintain Fording River’s capacity of 10 megatonnes of coal a year — well over the daily coal production requirement for a review.

However, the company estimates the new Castle area will take up 2,550 hectares of land “not previously permitted for disturbance,” or 36.5 per cent of Fording River’s current land area — so, falling short of that 50 per cent threshold.

A federal review is mandated only if both thresholds are exceeded.

But Teck’s land use breakdown is up for question.

The company calculates Fording River’s current land area as the land that is covered by its existing permits, which it puts at 6,993 hectares. Of this, however, Fording River only actively utilizes about 5,000 hectares — and by this calculation, the Castle project would represent a 51 per cent increase in the area of mining, qualifying the expansion for automatic federal review.

Teck estimates Castle’s carbon footprint at roughly 673,000 metric tonnes of CO2 equivalent (including carbon dioxide, methane and other greenhouse gasses) yearly, in keeping with Fording River’s current emissions. This is only an approximation, however.

Over half of the greenhouse gas emissions at Teck’s sites is caused by fossil fuel combustion, particularly from the use of diesel trucks for transport and haulage.

While Teck claims to be exploring alternatives, including the electrification of its truck fleets, the Castle project would likely require an even greater use of fuel than Fording River. Preliminary maps provided by the company suggest a driving distance of approximately four kilometres between the processing plant at Fording River and the nearest Castle Mountain pit — and an even greater distance between Castle Mountain and the proposed waste rock storage pits to the north. In short, trucks will be driving more.

Teck also reports having drastically reduced its overall carbon footprint — for all its operations including coal, oil and gas — since 2011. But emissions at Fording River itself have actually grown 34 per cent during that time, from 500,000 tonnes in 2011 to the 673,000 figure in 2018.

But this number only represents emissions from operations at the mine itself (a part of the reason for this increase may be the expansion of Fording River in 2015 that included a new set of pits).

There’s also transport: most of the coal from the Elk Valley travels over a thousand kilometres by rail to Vancouver and is then shipped across the world, primarily to China.

And there’s its end-use emissions when the coal is turned into steel.

In 2019, Teck estimated the use of its steelmaking coal produced a further 73 megatonnes of CO2 globally (for reference this is just above what the Alberta oilsands as a whole emit).

Fording River accounts for one third of the company’s total coal production and the Castle project is expected to continue this level of production for several decades. This means use of the coal mined there could generate a further 24 million tonnes of CO2 emissions every year, unless mitigated, into the 2050s — the equivalent of 3 per cent of Canada’s entire annual greenhouse gas production.

A meandering bend in the Upper Fording River where high levels of selenium have been measured and a population of westslope cutthroat trout recently experienced a 93 per cent population crash. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

From mining to use, the steelmaking coal extracted from the Elk Valley releases as much greenhouse gas into the atmosphere as every other activity in British Columbia combined.

Teck’s steelmaking coal is “needed to build infrastructure such as schools and hospitals, as well as clean energy projects like wind turbines and solar panels,” Chris Stannell, the company’s public relations manager, told the Narwhal.

He added there are no adequate alternatives to coal in the making of steel — for reasons of cost, quality, and/or carbon footprint — and that “Teck’s steelmaking coal has among the lowest carbon intensities in the world,” meaning its carbon footprint is lower than that of competitors.

Critics argue steelmaking coal is in fact an extremely detrimental process. Globally, the industry’s carbon footprint accounts for “as much as the entire aviation industry,” according to Lars Sanders-Green, a mining analyst for conservation organization Wildsight. Viable alternatives to coal in the making of steel already exist, he added, including methods using electric arc furnaces or

On top of all of this, Teck does not systematically track the methane released into the air from its mining activities. It is only estimated and translated to a CO2 equivalent in its calculations.

Critics of the project have identified three main areas of concern with Teck’s Castle proposal: water pollution, air pollution, and wildlife impact.

High levels of selenium in local waterways have been linked to waste rock from Teck’s existing Elk Valley mines. This is a longstanding problem: when Teck last expanded Fording River, in 2015, its Environmental Assessment certificate was conditional on an independently-monitored plan to protect the population of cutthroat trout downstream of the mine.

Instead, the trout population in the waters directly downstream of Fording River has collapsed over the last two years, and in some Elk Valley rivers today the selenium concentration is four times the legal maximum for drinking water. Authorities from local Indigenous Nation Councils to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency have demanded explanations for the pollution, and in late 2018 Canadian federal prosecutors notified Teck it could lead to potential charges under the Fisheries Act. (“Discussions with respect to the draft charges,” according to the company’s latest sustainability report, are ongoing.)

Air pollution is also a problem. Castle is expected to discharge between 15 and 22 tonnes of sulphur dioxide into the air every year, but the main air pollutant from mining is particulate matter 10 (or PM10), a mixture of chemical airborne contaminants small enough to be inhalable into the lungs and possibly cause adverse health effects including respiratory illness and heart or lung symptoms, primarily in infants, children, and the elderly. Amounts of PM10 in the air at Fording River were recorded at higher levels than the Provincial Ambient Air Quality Objective on sixty-two days in 2018. As with water, however, the company’s management plan consists mostly of “new strategies and new equipment” to mitigate pollution. Critics say these strategies are not scientifically sound and revolve around experimental monitoring and treatment facilities that have little to no track record of meaningful success.

Finally, Teck’s initial project description identifies 58 blue- or red-listed plant species (one listed as endangered under Canada’s Species At Risk Act) and 55 blue- or red-listed wildlife species (six listed under SARA) that may be impacted by the Castle project. Possible disturbances also include destruction of bighorn sheep habitats and interference with several wetlands and mature and old growth forests “within the project vicinity.”

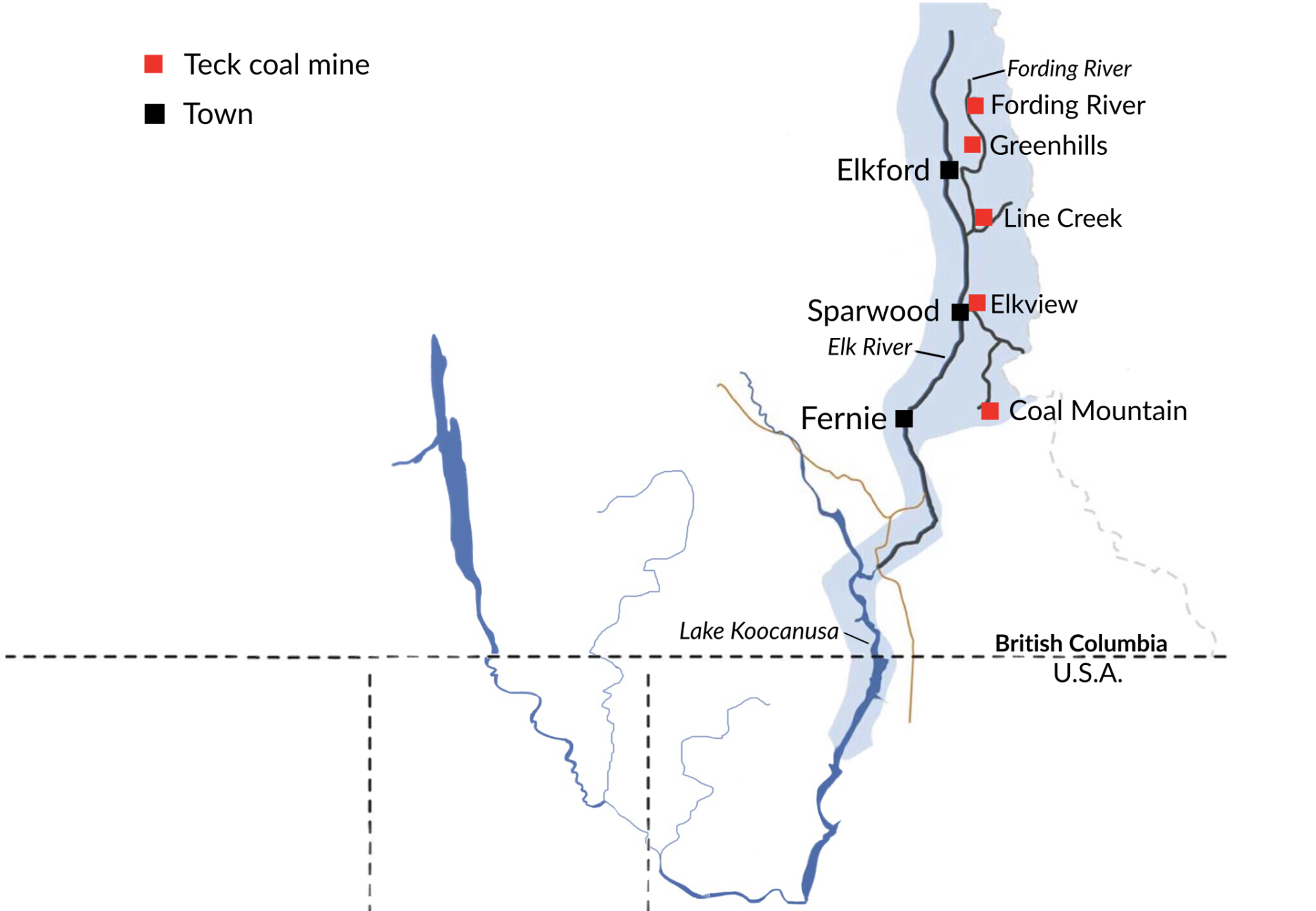

Teck’s five metallurgical coal mines are all upstream of the transboundary Koocanusa Reservoir. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

The public comment period of the B.C. Environmental Assessment Office’s initial project description period is open through June 22. Provincial authorities will then deliver a summary of engagement and a suggested direction for a detailed project description to be delivered by Teck before the end of 2020.

Teck hopes pre-construction on the Castle project would begin in 2023, with the mine ready for production by 2026. Meanwhile, having received a request to designate the Castle project for federal review, the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada is currently analyzing the project, and must make a recommendation to the Minister of Environment and Climate Change by August 19.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...

From investigative reporting to stunning photography, we’ve been recognized with four 2024 CAJ Awards nods...

The Narwhal is expanding its reach on video platforms like YouTube and TikTok. First up?...