The Right Honourable Mary Simon aims to be an Arctic fox

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

It was an early morning in May when I drove past rows of houses and turned into an industrial park in Richmond Hill, Ont., to visit one of the remaining places you can find redside dace — a surprising one given this species of minnow is extremely sensitive to urban development.

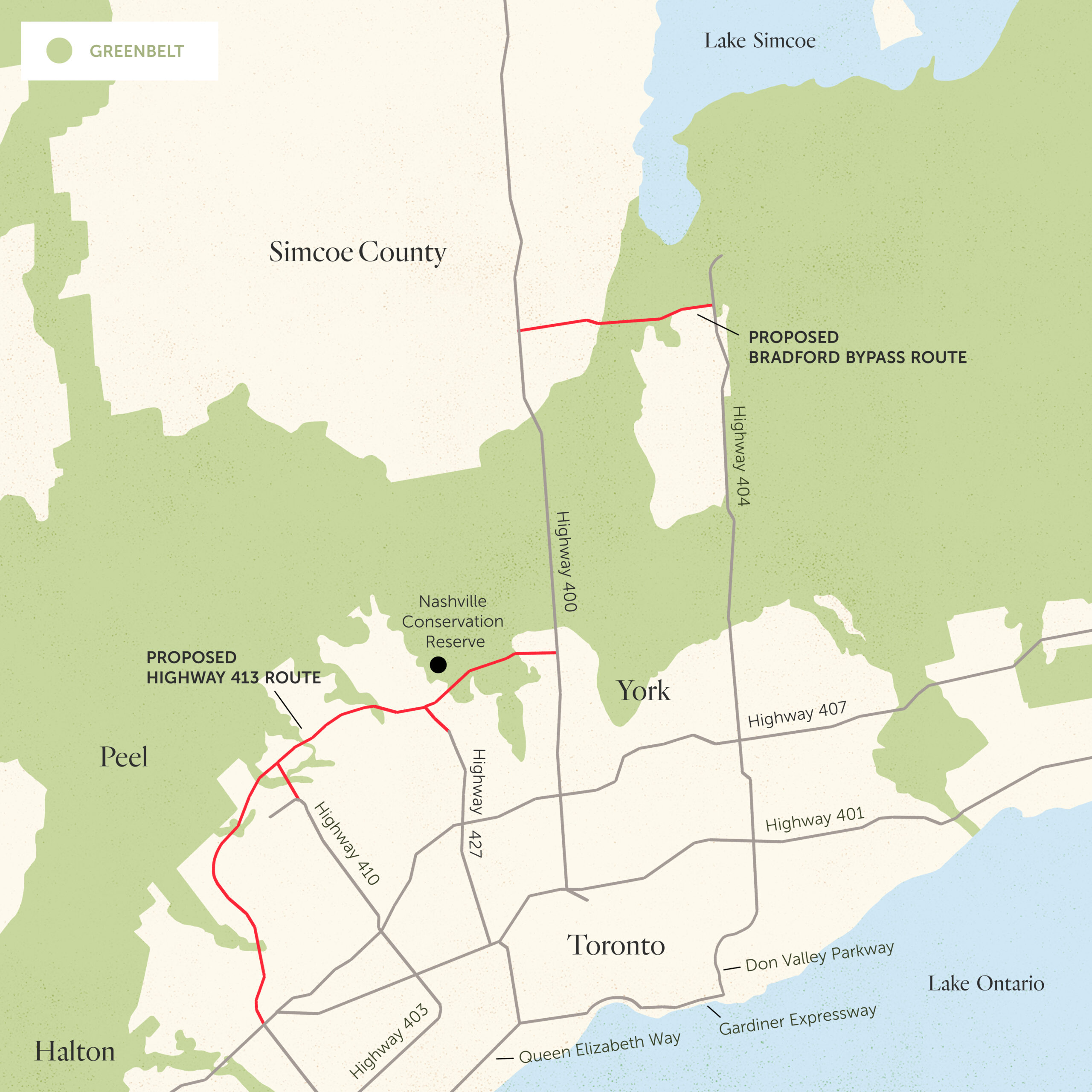

This small silver minnow with its namesake red stripe has received outsized attention as one of the endangered species whose limited habitat would be cut through by Highway 413, a signature road project for Ontario’s Doug Ford government. The 60-kilometre route rings around the suburbs north and west of Toronto, crossing 85 waterways and the habitats of 11 species at risk — including redside dace.

Now found only in small, fragmented populations in creeks and rivers from Whitby to Hamilton, redside dace were once abundant across the Greater Golden Horseshoe of southern Ontario.

In June, the federal government released a recovery strategy and action plan for redside dace, with a goal of ensuring “the long-term survival and recovery of redside dace in Canada by addressing key threats to the species and its habitat,” a Fisheries and Oceans Canada spokesperson told The Narwhal.

It comes as the Ontario government has been trying to weaken protections for the fish and the federal government’s environmental review of the Highway 413 project, which could have prioritized the endangered minnow’s protection, was compromised by challenges to the Impact Assessment Act. But despite the urgent need for action, the federal government’s much-delayed new strategy reiterates what’s already been proposed provincially to help the endangered fish recover, and misses key points.

The hope lies in the federal government issuing a protection order for redside dace, and using its power to deny projects that harm this fish or its habitat. But this power is not new, and since the recovery strategy lacks mandatory development limits and fails to emphasize severe population declines, it’s unclear how it will help Fisheries and Oceans Canada make strong arguments to deny projects that harm redside dace.

In the creek running behind the Richmond Hill industrial park, I watched as redside dace broke into small groups to spawn. Some leapt into the air to feed on flies and other bugs, a unique trait that helps connect terrestrial and aquatic systems.

The water was slightly murky, with a sediment layer on the creek bottom, and its temperature was already at 21 C, the higher limit preferred by redside dace. With myriad development nearby this creek — a golf course, parking lots, roads, houses and industrial buildings — and more proposed upstream, it’s hard to say if this population will still be here next year or the year after.

With 80 per cent of the Canadian redside dace population living in the Greater Toronto Area, where there is major development proposed in most watersheds they use, it seems unlikely the species will survive at all in southern Ontario — despite the new recovery strategy.

Redside dace have been officially considered under threat for 15 years. The Committee on the Status of Species At Risk in Ontario listed them as endangered in 2009 and they were added to the species at risk list that same year, gaining full habitat protection under the provincial Endangered Species Act in 2011. That habitat is defined as any part of a stream they have occupied for the last 20 years — a time period the province tried to reduce to 10 years, before backtracking a couple of weeks ago on that particular attempt to water down protections for the fish.

Federally, redside dace were assessed as endangered by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada in 2007, although they weren’t listed as endangered by the federal Species At Risk Act until 2017.

In the decade since the 2007 federal assessment, the range in which redside dace live has shrunk by 4.4 per cent, the area within their range that they actually occupy declined by 47 per cent and their population declined by a staggering 81 per cent. In 2017, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada projected the population could decline even further in the next 10 years by more than 50 per cent — and we are seven years into that period.

In a 2019 assessment of the population, Fisheries and Oceans Canada stated this rate of loss means “there is no scope for allowable harm to the population.” This was based on the federal agency’s own science, which concluded “any human induced mortality or habitat destruction would jeopardize survival or recovery.”

Their sensitivity to development makes them a measure of the health of an ecosystem — and their disappearance suggests our efforts to maintain that health are failing.

Federal recovery strategies for species at risk are meant as planning documents that identify how to stop or reverse the decline of a species — the actions provide the best chance of increasing both the size of a population and the area in which it lives.

Curiously, the new federal recovery strategy for redside dace, prepared by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, does not state that any harm to the fish jeopardizes its survival — as the department’s own assessment did in 2019 — nor does it reference the severe population decline. Instead, the strategy reiterates much of the same list of proposed measures already identified through the Ontario government’s recovery strategy — measures that are either not being followed or not working.

Within the federal strategy, the actions for seeing redside dace recover are prioritized as high, medium or low.

It suggests raising fish in hatcheries is a high priority. But with suitable habitat being lost to development, there are fewer and fewer places to release any hatchery-raised redside dace, especially since stocking in the same place as wild populations harms those wild fish.

Identifying how urban development and agricultural practices contribute to population declines is listed as only a medium priority in the federal strategy. Yet this information is crucial to help populations recover because there is a glaring absence of science on this topic, and development is the main cause of population declines.

Where there is science, it isn’t necessarily followed by the strategy. Redside dace prefer cool water below 20 C, but the recovery strategy lists the target temperature as a maximum of 24 C. This higher target means warm water from urbanization and storm runoff will be allowed to enter streams, degrading habitat quality for not just redside dace but other fish like brook trout, as well as insects that provide food for animals in the water and on land.

The lowest priority in the strategy was measuring the health of redside dace habitat and investigating the feasibility of restoring its water quality, streamside vegetation and the movement of water. Strangely, this was ranked as a high priority in the draft version, but downgraded in the final.

The Fisheries and Oceans Canada spokesperson said the changes between different drafts of the strategy “reflect ongoing consultations with experts and stakeholders, as well as new internal guidance on prioritizing recovery measures.”

They added “all the measures included in the strategy are considered high priority. However, we needed to rank them to ensure the most critical actions are addressed first.”

The priorities are laid out to focus on immediate recovery measures that have a high impact in addressing population decline and threats, they said. However, the first priority listed in the strategy is to continue working with local planning authorities to consider the protection of critical redside dace habitat — which they’ve already been doing with little marked success and, as the strategy states multiple times, with limited understanding of the significance of different impacts.

The release of the strategy requires the federal fisheries minister to make an order under the Species At Risk Act prohibiting the destruction of redside dace habitat by Jan. 25, 2025. Having the protected habitat defined federally does provide a backstop, should Ontario again tinker with its own definition of critical redside dace habitat. Fisheries and Oceans called this “an additional tool to ensure the legal protection of redside dace critical habitat,” but also stated, “The 2024 recovery strategy does not grant new authority beyond what already exists.”

The department can still authorize development in redside dace critical habitat, as long as “the activity does not jeopardize the species’ recovery,” the department wrote.

Fisheries and Oceans has authorized 154 permits under the Species At Risk Act since redside dace were listed in 2017, and the species continues to decline. And indirect impacts on critical habitat, like runoff from a highway, still do not require this federal approval.

So how will the new strategy allow Canada to rein in Ontario’s appetite for development, if it’s operating by the same rules?

The province’s track record of protecting redside dace from development is zero, according to Ontario’s auditor general. Provincial permits to harm redside dace or their habitat have never been denied.

Overall, the province approved about 500 permits from 2007 to 2020 for activities affecting redside dace. Under “overall benefit” permits — which purport to only allow the permit holder to harm a protected species if there will be an added benefit, like from the creation of additional habitat — there was more damage allowed to redside dace habitat than what was restored in all eight cases over two years found by Ontario’s auditor general.

And it’s not just private companies doing the damage. The auditor general found the Ministry of Transportation obtained “an overall benefit permit in 2021 for a highway crossing over a creek that allowed the damage and destruction of 0.46 hectares of redside dace habitat, but only required 0.08 hectares of habitat to be created or enhanced.”

In 2016, Ontario’s Ministry of Environment published best management practices for development in redside dace habitat. It stated that the greatest threats are physical changes to the streams, including changes to flow, temperature and turbidity, as well as the removal of streambank vegetation where insect prey live. Contaminated runoff from intensive agriculture and stormwater management ponds are also a massive threat to this fish.

We know the general reasons why we’re losing this little silver fish. We also have laws that have protected their habitat for more than a decade. Clearly, something isn’t working.

The listing of redside dace under the Endangered Species Act almost 15 years ago should have stopped harmful activities. Environment Canada recommends development should be limited to less than 10 per cent of a watershed, but the Ontario government continues to issue development permits well beyond this. And every year, the population of endangered redside dace is estimated to shrink by more than five per cent.

All of the current legal protections for this species have failed, and the new federal recovery strategy and action plan provides no new information on how to protect against what has proven to be the main driver of population declines — urbanization and the resulting effects on stream habitats, water quality and flow and groundwater sources.

Instead of setting clear thresholds for development and guidelines for how to reduce known threats, this strategy ranks monitoring as a higher priority than actually identifying and stopping the drivers of population loss.

Meanwhile, the provincial government has plans to begin work on bridges and other early infrastructure for Highway 413 next year. And the federal government has already stated “no additional restrictions for industry stakeholders are anticipated” as a result of redside dace’s listing under the Species At Risk Act.

Redside dace need strong legislation that clearly states how much land can be developed and altered, and what must be left in a natural state. They need governments willing to say “no” to permits that harm their habitat. Unless the federal government takes a much stronger stance than it has so far, and than the provincial government has shown, the future of redside dace in southern Ontario is bleak.

Soon, I fear, I’ll be watching the extirpation — or local extinction — of this tiny unique fish.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...