‘Afraid of the water’? Life in a city that dumps billions of litres of raw sewage into lakes and rivers

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Despite vocal public opposition, the regional government for the East Kootenays has paved the way for a new estate-style neighbourhood just outside Fernie, a small city nestled in the Rocky Mountains of southeastern B.C.

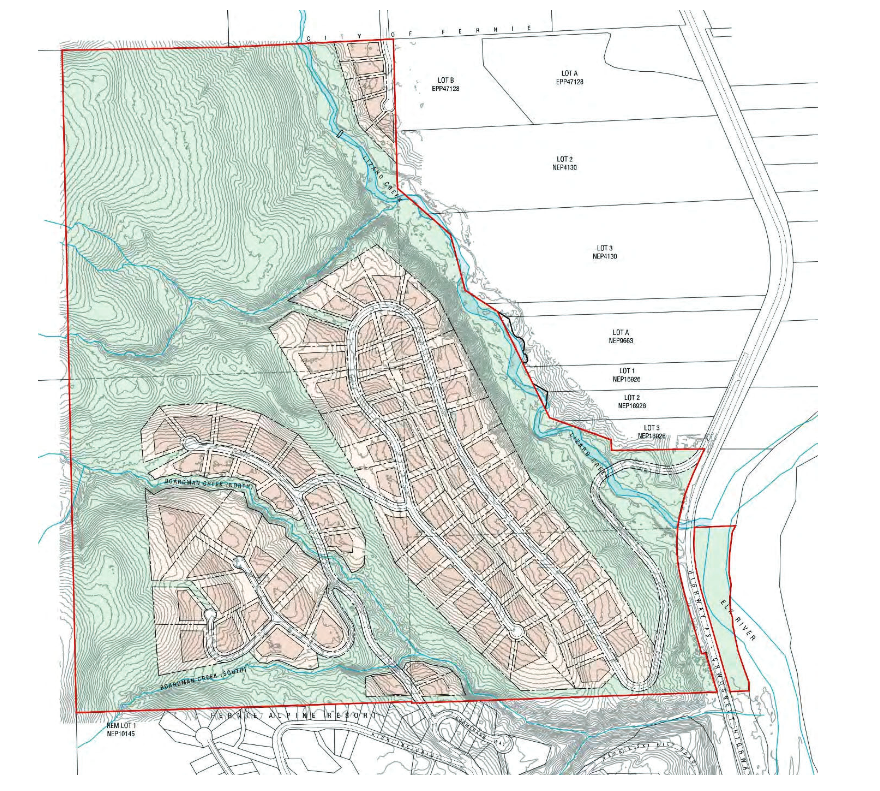

The proposal to rezone 185-hectares of private property, known as the Galloway Lands, to develop 90 single-family homes passed third reading on May 12, with the support of nine regional directors. Six, including Fernie Mayor Nic Milligan, voted against it.

Third reading is typically the last opportunity for any debate or amendments to a proposed bylaw before it is adopted. In order for any changes to be made now, this vote would have to be repealed and taken again.

“We are at an important crossroads and the decision we make today will shape the trajectory of our entire region going forward,” Milligan said, as he urged his colleagues to reject the proposed rezoning.

“The mixed, authentic community of service workers, nurses, teachers, tradespeople, coal miners, small businesses, young families and young single people is being lost in favour of an exclusive playground for the wealthy,” he said. “Our communities are all being hollowed out.”

“The primary issue are ecosystem services that these lands offer, services that we cannot replace once they’re gone,” he said.

The proposal has faced considerable criticism over concerns it would sever an important grizzly bear travel corridor, threaten vital fish spawning habitat, destroy part of a network of well-loved Nordic ski trails and fail to resolve an affordable housing crisis.

The developer, however, has said the project will improve affordability issues in the city through a “trickle-down” effect by making more housing available and has committed to setting roughly half the land aside for conservation and recreation.

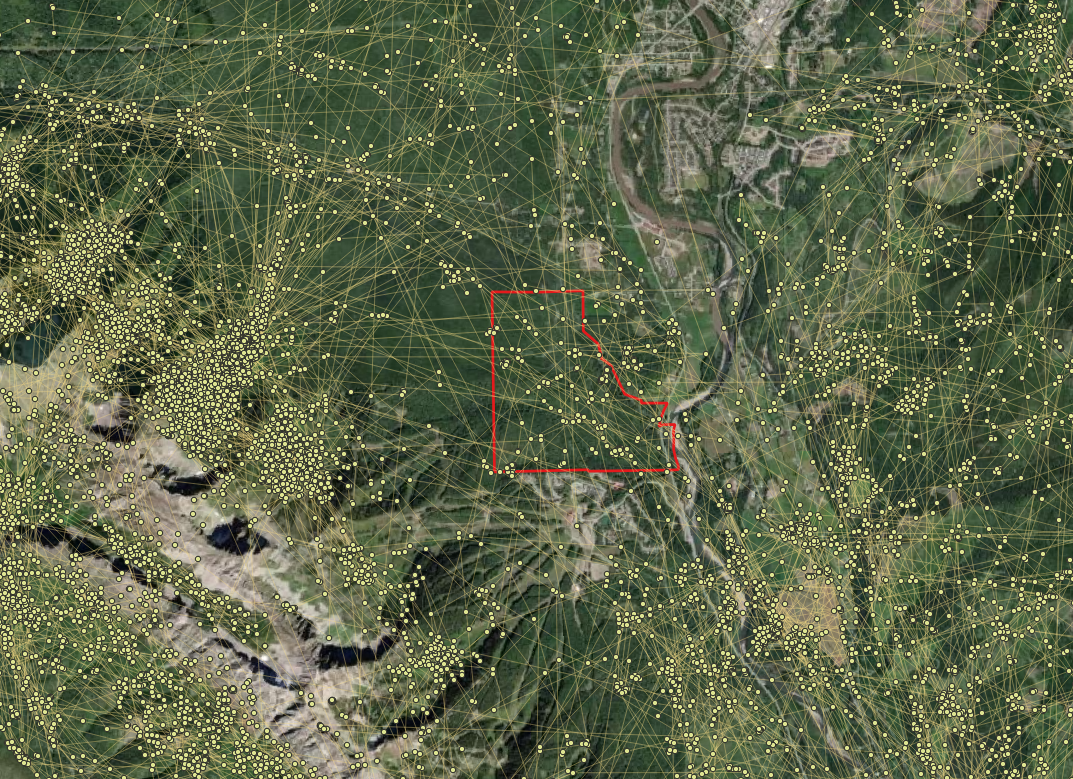

Because the land sits outside Fernie’s municipal boundaries the decision fell to the Regional District’s board of directors, which includes representatives from nine municipalities and six rural electoral areas. Thomas McDonald, the regional director for the Elk Valley, which includes the Galloway Lands, supports the project.

“I’ve been continuously engaging with all members of the community,” he said. “I’ve seen a much bigger picture than just the public hearing.”

“I believe that this proposal balances environmental concerns, public access and economic growth,” he said at Friday’s board meeting before voting in favour of the rezoning.

David Wilks, the mayor of Sparwood, a community about 30 km northeast of Fernie, also supported the rezoning. He noted the developer addressed several community concerns with the initial pitch, adjusting for instance a plan for wells and septic systems to connect instead into a community water and sewer system.

“We will never have a perfect plan,” he said, “but I feel that if we don’t move forward, we are sending a message to developers of private land that you are not welcome here.”

In the Fernie area, the proposed development has stirred considerable debate about what development for the future should look like and how those decisions get made.

Randal Macnair, a former Fernie mayor and Elk Valley conservation co-ordinator for Wildsight, a regional environmental charity, said he was “very disappointed” with the outcome of the vote.

Several hundred people had voiced opposition to the proposed rezoning through the public hearing process.

Prior to the vote, Both Milligan and Norma Blisset, a director for Cranbrook, urged the board not to ignore the public feedback.

“Do not minimize the value of the public hearing,” Milligan said. “We may not recover from the depth of cynicism and mistrust.”

That the decision is being made by the regional district at all is a concern for Macnair, because most of the elected officials on the board are not accountable to the affected community, he said.

In a statement to The Narwhal, Karen MacLeod, planning supervisor at the Regional District of East Kootenay, noted “land use decisions under the jurisdiction of regional districts are routinely made by the respective Board of Directors utilizing this representation model across B.C.”

Macnair called it “a crisis of democracy.”

At the same time, there are concerns that the policies meant to guide land use management and community development are out of date.

“Galloway is just a tipping point,” Janice Kron, who lives near the proposed development, told The Narwhal ahead of the decision. “It’s the watershed moment where we have to decide how we utilize the land in this region.”

The issues at play are not unique to Fernie. Whether it’s port expansions in Delta, B.C., or urban sprawl in the suburbs of Vancouver and Toronto, countless communities are grappling with how to balance competing pressures on the land in the face of global biodiversity and climate crises.

Here’s what you need to know about the proposal to develop the Galloway Lands:

Fernie is a picturesque city built on the banks of the Elk River and surrounded by towering mountain peaks. More than 6,000 people call Fernie home, and tourists flock to the region for its access to hiking, mountain biking, skiing and fly fishing. It’s also the largest community in the Elk Valley, a region that’s seen a major expansion of metallurgical coal mining and logging over the last several decades.

As the human footprint in the region expands, it’s encroaching on the lands and waters that wildlife, like grizzly bears and westlope cutthroat trout, rely on.

With three times the density of Banff National Park, the Elk Valley grizzly bear population is “moderately dense” and “fairly stable,” said Clayton Lamb, a wildlife scientist with Biodiversity Pathways, a research institute at the University of British Columbia. But there’s a “fragile balance” at play, he said.

Though the Elk Valley has plenty of good food for bears, mortality levels are so high that females can’t reproduce fast enough to replace the bears that die, which means the population is dependent on grizzlies that move in from other, less developed areas, Lamb explained.

At this point, scientists don’t really know what level of development could cause that dynamic to fail, he said. But the bears’ world is getting smaller as new developments sprout up.

Nasuʔkin Heidi Gravelle of Yaq̓it ʔa·knuqⱡi ‘it, which is part of the Ktunaxa Nation, said in an interview that the proposal to develop these lands is “disheartening.” The area is not only used by wildlife, which would be displaced by the development, it’s also home to traditional plants and medicines, she said.

“We all know the magnitude of building a subdivision, especially one with that many homes,” Gravelle said. It’s “going to completely wipe out an entire area, which means disrupting the animal corridor.”

The developer said he met with Yaq̓it ʔa·knuqⱡi ‘it in 2021 and reached out several times over the last couple years to discuss the project. But Gravelle said the consultation was “superficial” and didn’t offer a meaningful opportunity to guide the project. “It’s typical,” she said, “we see it all the time.”

The Galloway Lands sit between the City of Fernie and Fernie Alpine Resort, which includes a growing residential area. Though privately owned by Bud Nelson through his company CH Nelson Holdings Ltd., the land is used by hikers and mountain bikers in the summer and, in the winter, by the local Nordic ski club, which has an agreement with Nelson that allows them to use the land.

The community of Nordic skiers in the area has “absolutely burgeoned,” according to Macnair.

Today, the Galloway Lands are the “most-used and best Nordic terrain in the Elk Valley,” he said.

Jen Grebeldinger, an avid skier, said the community is “grateful” to have access to Nelson’s private lands.

Her kids started taking lessons when they were just three or four years old. Years later, cross-country skiing is still the thing that gets her family out of bed on Saturday mornings in the winter. She’s seen “moose tracks and hawks in the sky” while gliding through those trails and spent countless hours with friends. “It’s just a beautiful community of people who just love to be outside,” she said.

Alongside concerns about lost trails, numerous people who have spoken out against the proposed development raised concerns about the potential harms to wildlife.

Ultimately, Macnair said he’d like to see the area be included in the adjacent Mount Fernie Provincial Park. If the proposed development falls through, he said, “I’m sure we could find the money to make that happen.”

Reto Barrington, a former Canadian Olympic skier and local developer, is the person proposing the new housing project through a company called Handshake Holdings.

In a statement to The Narwhal, Barrington said: “I want the people of the Elk Valley community, a community I am very much part of, to know that we are committed to preserving the beauty and integrity of the Galloway Lands.”

“We are confident and committed to ensuring that environmental protection, recreational opportunities and a new neighbourhood will work together,” he said.

Barrington said he sees his proposed development as a compromise between what could one day be a denser, more urban expansion through the area and the complete protection some quarters of the community are calling for.

The land is “clearly in the growth corridor” for the Fernie area, he said in an interview, pointing to both the city and the regional district’s current official community plans.

Back in 2014, when the regional district adopted its official community plan for the Elk Valley, most of the land in question was considered as a future expansion area for the local ski resort.

Because the resort is expanding in another direction, regional district staff said changing the designation for the land in the official community plan “is appropriate.”

The plan tends to favour “more compact development with opportunities for more efficient use of land,” regional district staff said in a March 31 report. But in their view, the proposed development balances the conservation objectives with rural residential development and public access for recreation.

Macnair, however, worries there “has been a lack of critical analysis on the staff’s part as far as the impacts and ramifications of the development.”

Under the current zoning, the lands could be used for anything from logging to one single-family home per land parcel. If the owner were to subdivide the properties, the zoning would allow for lots that must be at least eight hectares in some areas and 60 hectares in others, according to the regional district’s Elk Valley zoning bylaws.

Barrington is proposing 90 lots but rezoning the properties could in theory allow for more development. The zoning could allow for up to 195 lots, though this doesn’t account the creek, roads and other factors that could limit building, into consideration, according to a March 31 report from the regional district.

According to Handshake Holdings, the topography and a minimum lot size of 0.4 hectares under the proposed zoning mean “the maximum number of lots actually possible within the development lands (outside the conservation parcel) is consistent with the proposed conceptual plan,” the report says.

As currently conceived, each property would be connected to sewer and water systems at the Fernie Alpine Resort and Handshake Holdings has proposed registering ‘no build’ covenants on each lot that would restrict building and landscaping to a smaller footprint within each property, preserving forested areas between them.

Fernie Alpine Resort is part of a company called Resorts of the Canadian Rockies, owned by Alberta oil executive Murray Edwards.

In a March letter to the regional district, the vice-president of Resorts of the Canadian Rockies said the company supports the proposed development, noting that “any increase in residents and visitors has a net benefit to the resort.”

Barrington said his vision would see 70 per cent of the forest cover retained across the property.

The developer says the setbacks from Lizard Creek, which runs along one edge of the property, would be larger than required and has proposed setting aside 94 hectares surrounding the neighbourhood for conservation and recreation, which could be transferred to a conservation organization to manage. Barrington, who hired the consulting firm Cascade Environmental Resource Group to review potential impacts of the development and suggest measures to reduce those risks, has offered to make several commitments under a development agreement as an assurance that the land would be developed as currently proposed.

The Cascade report, which is not a peer reviewed scientific study, concluded that as long as the recommended measures are taken to reduce potential impacts from construction and operation “the Galloway Lands appears to be suitable for the proposed development.”

Martin Vale, another local developer, was one of a handful of people who spoke up for the development at an online public hearing in early May. He called it a balanced proposal that would provide a home for the local Nordic ski club and warned that if it doesn’t move forward the public could risk losing access to these lands entirely.

A lot of the hiking and biking in the area today seems to be unsanctioned use of private lands. Barrington said his proposal would secure community access to the lands for recreation.

Area resident Ron Smith, who also spoke in favour of the development, highlighted in particular the potential for a trail linking the ski hill to the provincial park.

The B.C. Ministry of Water, Lands and Resource Stewardship, however, has recommended that the proposed project should not be approved.

“The project area provides valuable habitat for multiple species and is currently relatively undisturbed; this project would permanently remove functioning habitat,” a B.C. government biologist wrote in an email to the regional district in late March.

Lamb, who lives in the Elk Valley, was contracted by Wildsight and the Elk River Alliance to assess the potential impacts of the proposed Galloway Lands development on grizzlies.

He’s been studying grizzly bears in the Elk Valley for the last decade and said data from collared bears he tracks show a number travel through the Galloway Lands.

Between the city on one side and the resort on the other, the bears are funneled into this undeveloped channel as they move throughout the valley, he said.

“The Galloway Lands are basically part of that movement corridor that animals would use to go around the city of Fernie,” he said, “just like water would flow around a rock in a river.”

“It’s hard to imagine a situation where there would be 90 properties there and additional recreation use, that would still provide an effective corridor for grizzly bears,” he said.

Grizzlies in Western Canada are currently considered a species of special concern by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, a scientific body that advises the federal government on which species to list under the federal Species at Risk Act.

If the development goes ahead, Lamb said he expects there will be a period where grizzlies continue to move through the area. “They are taught by their mum to move through these lands, some of them,” he said.

But at some point, there will also be 90 or so homes that may attract bears to some degree or another.

“We’ll probably see a bit of conflict to begin with,” Lamb said. “In some cases, it might actually be very dangerous,” he said. “You might not want all those people and grizzly bears clashing on that small parcel.”

Over time, bears will use that corridor less and less.

“Either bears will get killed in that area as a result of conflict with people or they’ll just start avoiding it because of the risks and just how busy it is,” he said.

“If I had the magic wand,” Lamb said, “I would much prefer to see development inside the city’s footprint that is already largely avoided by wildlife.”

Ultimately, Milligan said with a pause, there’s “an opportunity to create a better project for the region.”

The risk that the Galloway Lands could be logged if the rezoning was rejected came up several times during the public hearing process and again during the board meeting on May 12.

Mcdonald noted at the board meeting that “currently there is not a permanent mechanism to prevent clear cut logging, protect environmentally sensitive areas or ensure public access to the recreational trails on the property.”

In contrast, he said, the proposed development plan would ensure public access to trails and protect a large stretch of forest through the conservation parcels, setbacks from Lizard Creek and by restricting building to a certain footprint on each property.

Milligan, however, said “personally, I don’t think logging is a worse outcome than 90 homes that will never go away and a road and a bridge over Lizard Creek.”

Ahead of the meeting, Lamb said logging, done in a responsible way, “would be orders of magnitude better from a wildlife perspective than developing it with houses.”

The disturbance from the actual work of cutting down trees would be for a limited period of time, he noted. It could also open up the landscape, which could allow more good food for wildlife to grow back.

“But even if it was clear cut, it would probably still be better than having 90 houses in there, to be honest, because it will grow back,” he said.

It has before — the land was logged 30 years ago.

Much of the existing trail network would be lost if the development goes forward.

Barrington offered the Fernie Nordic Society the option to buy the land that would be set aside for conservation and recreation surrounding the proposed neighbourhood for $1, which would allow the club to establish a permanent home on the land, according to correspondence posted on the society’s website.

But the deal would depend on the ski club “providing demonstrated public support for the land use application,” the letter said.

Rather than publicly supporting the rezoning application, the ski society president said subject to approval of its board, the club would be open to engaging in a partnership agreement once the land use decision is made, according to an email posted to the club’s website.

Whichever conservation group ends up taking over management of the conservation lands, Handshake Holdings has said the organization would be required to reach an agreement with the Fernie Nordic Society, to allow for the development of new trails that “meet suitable grade requirements,” and to work with other trail groups.

Macnair warned, however, “the land they’re supposedly going to be leaving for trail systems is steep slope,” he said. “It’s completely unsuitable for Nordic trails.”

In a valley heavily impacted by industrial, urban and recreational development, Lizard Creek is “still in relatively good condition,” said Lee-Anne Walker, a local environmental educator, making it a “rare and unique creek.”

It offers some of the best spawning habitat for westslope cutthroat trout, a species of special concern, found throughout the valley.

“With so many of the tributary creeks being affected by mining and logging … we need to set aside creeks that are productive and can feed the Elk River with healthy populations of westslope cutthroat trout,” Walker said.

Barrington agrees the creek is an important habitat. He noted the proposed development setbacks from the creek are larger than required and that the area along the creek is proposed to be off limits for recreational development.

But Stella Swanson and Leslie Frank, whose property backs onto the Galloway Lands, worry the effects of increased recreation could be difficult to control.

Frank said he and Swanson have happened upon unsanctioned trails on their own property. “Right along the bank of the creek people have proceeded deep into our property, making their own trails with chainsaws, cutting down large trees, like 12 to 18 inches in diameter, leaving them scattered all over the place,” he said.

Mount Fernie Provincial Park, which is adjacent to the Galloway Lands, is just one example of an area that’s “almost loved to death,” Swanson, an aquatic biologist, said. Informal trails along Lizard Creek in the provincial park have caused the banks to slide, sending a rush of sediment into the water, Swanson said.

The concern is that more informal trails along the creek could put the quality spawning habitat at risk.

City Councillor Kyle Hamilton said Fernie has a fair number of four-to-five-bedroom family homes and quite a few studios and one-bedroom apartments. But a key gap in the community’s housing stock is those two-to-three-bedroom homes for families.

Though he credits Barrington with adjusting his original proposal to address several community concerns, Hamilton said he personally remains worried about the idea of building more single-family homes.

“There’s a lot of development currently happening,” he said. “What we don’t have in Fernie and what I know is a struggle in other areas are those more dense developments.”

A November 2021 report on the housing needs in the rural areas of the Elk Valley identified a lack of housing for people who work in tourism and hospitality as well as seniors and a lack of low-income housing options.

“Although improvements have been made in this updated proposal, the development does not address the fundamental housing needs in the area,” Interior Health’s community health facilitator and environmental health officer wrote in a letter to the regional district.

“In rural settings, we recommend clustering density toward settlement areas, and maintaining the integrity of large parcels of land,” they said.

Looking into the future, Hamilton said, “it’s probably inevitable that the Galloway Lands will end up getting developed at some point, but how do we ensure that that development is optimized for the needs of the community?”

That’s a concern for Gravelle as well. “We hear about it all the time, people leaving Fernie because they cannot afford to live there,” she said. “We know there’s a need for housing, but it’s not for million-dollar housing.”

“Do we want a Whistler or mini Banff? I don’t think so,” she said.

Barrington, who has attended a meeting of the Fernie Housing Solutions Working Group, said he doesn’t think the Galloway Lands, given their relative distance from city services, are an appropriate place for an affordable housing development.

“There’s plenty of other land where it is appropriate that’s sitting there waiting to be developed already,” he said.

At the same time, there are people who would look at the development he’s proposing and think “this is what I’ve been looking for,” he said. “It’s a product in the market that there’s a demand for.”

He added that “the construction of any houses has a trickle-down effect on the housing stock.”

For some in the Fernie area, a major sticking point is that the Elk Valley official community plan, a policy that’s meant to guide community planning and land use decisions, is almost a decade old.

“It is totally out of date,” Kron said. “It’s left elected officials at the Regional District with “no guidelines, nothing to help them decide what is the most important for this community.”

Though the lands are not within Fernie’s borders, the city also has an interest in whether the development moves forward. As the closest community, any new residents would be likely to shop in Fernie, send their kids to school there and visit the doctors in town.

With both the City of Fernie and the Regional District of East Kootenay set to update their official community plans this year and next, the city said it does not support an “amendment of this magnitude without significant public engagement.”

“This is an important decision that is going to have lasting legacy impacts,” Hamilton said. “I feel it would be really prudent for the [official community plan] update to occur, for that in-depth consultation to occur,” he said.

When asked about calls to update the official community plans before a decision on the Galloway Lands is made, Barrington said, “the irony would be that, born out of a need to compromise, my project would appear because it’s the only way you thread the needle,” between the potential for higher density development down the road and calls to conserve the land as a park.

Many residents in the valley disagree. “It’s low density, automobile-based development,” Macnair said. “That’s not what we need in the future.”

Updated May 12, 2023, at 4:43 p.m. PT: This story has been updated to reflect the discussion and vote at the Regional District of East Kootenay board meeting on May 12

Corrected May 15, 2023 at 3:27 p.m. PT: An earlier version of this story said developer Reto Barrington sits on a local affordable housing committee. It has been corrected to say Barrington attended a meeting of the Fernie Housing Solutions Working Group

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

Break out the champagne: Emma’s storied life and leadership in journalism has earned her the...