Celebrating 7 years of The Narwhal — and gearing up for the next 7

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

“Are you poor enough?”

That’s the question Crystal Lameman, government relations advisor and treaty coordinator for the Beaver Lake Cree Nation, said she felt she had to answer when she entered the Alberta Court of Appeals in the depths of the pandemic last summer. Lameman, along with the nation’s lawyer, was there to face down a stand of six Crown lawyers, representing both the province of Alberta and the Canadian government, who argued to a judge that Beaver Lake was fibbing when it said it didn’t have enough resources to cover its legal expenses.

At issue was whether or not Alberta and Canada should have to pay court-ordered advanced court costs for the Beaver Lake Cree Nation, which, since 2008, has been engaged in a costly treaty infringement case that argues the thousands of permits handed out for oilsands projects in Treaty 6 territory have made it impossible for Beaver Lake to exercise its Treaty Rights.

The courts previously ruled that Canada and Alberta should each cover up to $300,000 of the nation’s court costs per year to ensure the trial continues. The nation is also expected to pay $300,000 per year.

Advance court costs like these are rare. But in 2019 a judge ruled the nation’s infringement case was important to the public interest, and that it was “manifestly unjust” to force Beaver Lake to choose between funding the basic needs of the community or pursuing its Treaty Rights case.

But Canada and Alberta successfully appealed the decision, arguing the nation does in fact have funds — or potential access to funds — it could spend on the trial.

In court, Lameman testified the money the nation does have access to is reserved for things like repairing a water truck, which brings clean water into the Beaver Lake reserve community where more than 85 per cent of homes are not connected to the main water line. The money is also set aside for emergencies, like, for example, if the community’s school flooded — which, Lameman told The Narwhal, it did, just a few months after the advance costs ruling was overturned.

“Think about how, had we put all that money towards the litigation, we would have no money to fix our school,” she said.

Lameman said the court proceedings last summer were “humiliating.” She said the nation is rich in land, resources, and culture, but their financial wealth has been impacted by colonization and genocide.

“I can’t put words to it — knowing you’re having to uphold and respect and honour your ancestors. So you have to be very cautious about the way you talk about your people’s poverty,” she said.

Beaver Lake is now appealing the advance costs decision in the Supreme Court of Canada. Lameman fears a loss for the Beaver Lake Cree would set the precedent that a First Nation must exhaust all the funds it has to operate as a government to assert its rights in the colonial court system.

“If a nation cannot afford to bring claims, then we have no access to the courts, we have no way to uphold our rights,” Lameman said. “If the Alberta Court of Appeal decision stands, it’s basically going to shut the door on First Nations having their day in court unless they choose destitution.”

On the other hand, she said “this decision has the potential to allow First Nations to bring these publicly important claims that we otherwise couldn’t afford to bring.”

Karey Brooks, lawyer for the Beaver Lake Cree Nation, said this case is emblematic of a much larger issue.

“Indigenous communities fought hard to have their rights constitutionally protected,” she said. “But in practice, for many First Nations like Beaver Lake, they know they have constitutionally protected rights, but their ability to access the courts is really constrained by their resources.”

Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada told The Narwhal it could not comment on the Beaver Lake case while it is ongoing.

“We respect the decision of the Beaver Lake Cree Nation to pursue their claims through the courts,” a spokesperson said.

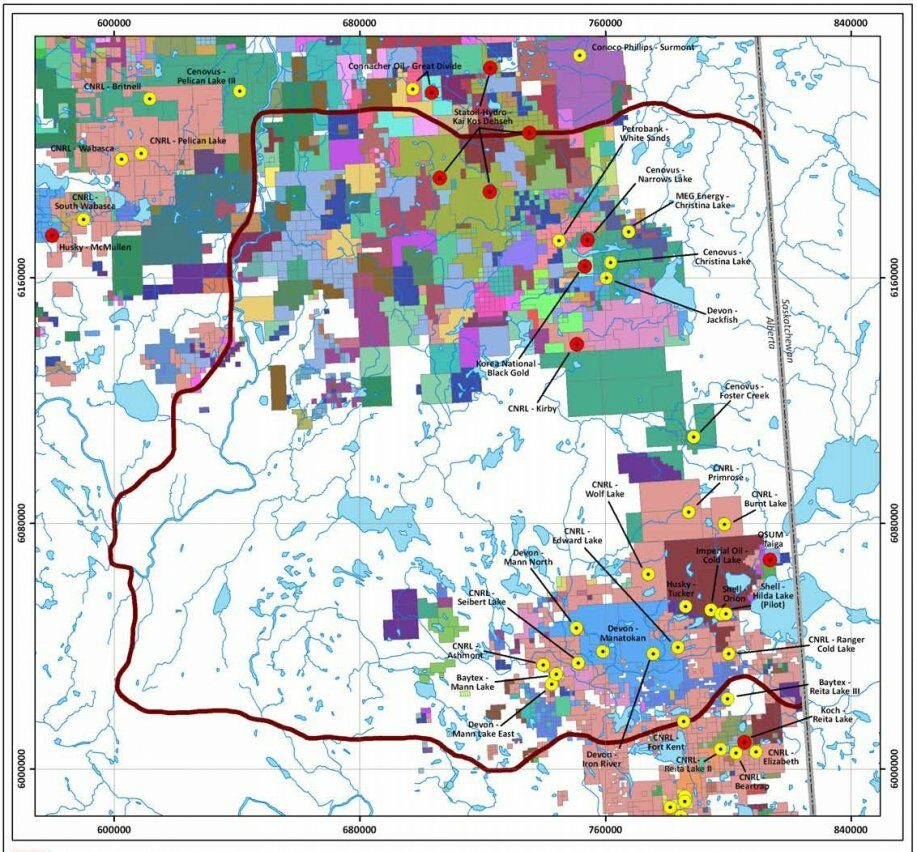

Beaver Lake has about 1,200 members, with roughly half living on their reserve in Treaty 6 territory, a two-hour drive northeast of Edmonton. Over the past several decades the territory has been significantly disrupted by the development of the Alberta oilsands, one of the largest oil deposits in the world. Oilsands are extracted through open-pit mining and in-situ operations and require the creation of vast tailings ponds, which cover 250 square-kilometres of former boreal forest.

Beaver Lake launched the precedent-setting treaty infringement case — the first to argue against the cumulative impacts of industry upon Treaty Rights — in 2008. The nation’s claim points to 19,000 permits granted for oil and gas activity for some 300 projects in the region as collectively causing environmental damage and preventing Beaver Lake members from hunting, fishing and living off the land. The case is scheduled to go to trial in the Court of Queen’s Bench of Alberta in January 2024.

What happens with the Beaver Lake’s infringement case could have significant consequences for the way industrial development is managed on Indigenous lands. But the advance costs case itself could also set new precedent.

At the centre of Beaver Lake’s cost case is a legal test that was established in the 2003 British Columbia (Minister of Forests) v. Okanagan Indian Band decision.

There are three elements to the Okanagan test: the party seeking interim costs must prove they “genuinely” cannot afford to pay for the litigation, the claim has to have merit and the case must be of public importance.

In the Beaver Lake case, Canada and Alberta did not argue whether the case had merit or was of public importance in their appeal — only that Beaver Lake could, technically, afford the litigation.

On those grounds the Alberta Court of Appeal overturned Beaver Lake’s advance costs award, noting Beaver Lake has access to $6 to $7 million through its Heritage Trust (which it established in 2014), the Indian Oil and Gas Canada Trust and other assets, including money crowdfunded for the nation by the Indigenous Rights non-profit RAVEN Trust.

“A plaintiff cannot fail to seek access to its own assets, and then argue it is … in need of litigation funding,” the court’s decision reads. “It is one thing to have insufficient funds to cover basic short-term necessities, but not all infrastructure and service deficits can be placed in that category.”

“Any applicant for advance costs could argue that it would like to spend its money on other things (e.g. more housing or better services), but such arguments cannot be used to sidestep this branch of the test.”

Brooks said the Crown is treating the First Nation like an individual who could exhaust personal resources, and not as a government with obligations to meet the needs of its people.

“What kind of government could go to its people and say ‘you’re not going to see any improvements in your community, we can’t improve our school or fix houses in dire need of repair, because for the next 12 years every dollar is going to go to this litigation?’ ”

She said the question before the Supreme Court of Canada will hinge on what it really means to be able to afford litigation.

But these arguments are painful to hear, Lameman said. “We’re tired. We shouldn’t have to be doing this,” she said.

“I never thought I’d be in an argument about whether my Nation was poor enough.”

Lameman said she sees a double standard in how First Nations are treated as governments.

“A court would not say, ‘Alberta, you need to be completely broke.’ The same application would not be applied to a municipality, to a provincial government, to the federal government,” she said.

“The systemic racism is so deeply embedded … The fact they feel they can do this to a First Nations government is the reason why we didn’t just let this die.”

“It’s the height of colonial patriarchy,” Susan Smitten, executive director of RAVEN Trust, told The Narwhal.

In their legal arguments, Crown lawyers noted that RAVEN Trust has raised $1.3 million from the public to support Beaver Lake’s legal action. “The level of future funding is uncertain,” the lawyers note.

Smitten said that the prior judgement, which split the costs three ways between Alberta, Canada and Beaver Lake, was based on the fact that RAVEN was supporting the nation’s legal costs. But RAVEN’s support seemed to be used against Beaver Lake when that ruling was overturned.

Smitten called the Crown’s arguments “unbelievable.”

“The position of the Crown, both federal and provincial, is ‘we don’t believe you. You’ve got money and you can just suck it up buttercup. You’ve got a water truck, so that tells us you’ve got enough money to run a multimillion dollar trial.’ ”

“No one in their right mind would think that there’s balance or fairness or equity in that.”

Susan said RAVEN exists to address the power imbalance between the “deep pockets” of government and industry and Indigenous Peoples to ensure Indigenous litigants can access the judicial system.

RAVEN also assisted the Squamish Nation, Tsleil-Waututh Nation and Coldwater Indian Band in their battle against the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion.

Khelsilem, spokesperson and councillor for Squamish Nation, said Squamish Nation budgeted about $150,000 per year in court costs. RAVEN’s Pull Together campaign raised almost $500,000 to assist the three nations in fighting the pipeline.

Khelsilem said Squamish Nation is fortunate in some ways, since it has more members and more capital than a nation like Beaver Lake. But he said they still face the same trade-off.

“We’re having to decide, do we fund Elders programs and health care for our members, or housing for our members, or do we challenge the government, which is not respecting our Indigenous Rights?” he said.

Rather than relying on court cases and “favourable judges,” Khelsilem said laws should be changed in government at the provincial, territorial and federal level.

“I think there’s now a shift happening, although it’s slow and complicated and messy … to develop new legislation that is more respectful and inclusive of Indigenous rights and interests,” he said.

“If we can actually change the laws of the country, then you can prevent these court battles from happening. We can force the bureaucracy, civil service and industry to follow certain legal obligations through legislation, not through case law decisions.”

Another cumulative effects case brewing in British Columbia has presented similar challenges for the Blueberry River First Nations, whose territory has been dramatically altered by oil and gas development, hydro facilities, agriculture and forestry over the last half-century.

Blueberry launched a suit similar to Beaver Lake’s in 2015 and their trial, which went to the B.C. Supreme Court, concluded in 2020 and the decision will be announced later this year. The Blueberry faced similar troubles to the Beaver Lake when it came to affording the legal proceedings.

In 2019, Blueberry successfully had hearing fees waived that would have applied to every day spent at trial and would have ultimately gone to the Crown.

Blueberry argued that the fees were inconsistent with reconciliation and Indigenous Rights under the constitution — and the court agreed.

The court ruled that when Indigenous Peoples must proceed to trial to protect their constitutional and Treaty Rights, it is “inconsistent” with reconciliation to charge them simply to access the court, and contrary to Section 35(1) of the constitution, which acknowledged and affirmed baseline Aboriginal Rights in Canada.

The Blueberry case was specific to hearing fees, and does not directly apply to the court costs in the Beaver Lake case, but the decision was still consequential when it comes to legal fees creating barriers for Indigenous Peoples. The B.C. Supreme Court’s ruling in the Blueberry case established, for the first time, that unaffordable hearing fees could not prevent Indigenous Peoples seeking to protect their Section 35(1) Rights or Treaty Rights from battling infringements.

Beaver Lake Cree Nation is inviting other First Nations as interveners in their case, and West Moberly First Nations from B.C. was eager to participate.

“First Nations don’t have the money for doing this kind of stuff,” said Roland Willson, elected Chief of the West Moberly, which launched a lawsuit in 2019 against the $16 billion Site C dam, arguing the project infringes on their Treaty 8 rights. The Site C dam will flood 128 kilometres of the Peace River and its tributaries — about the equivalent distance of driving from Vancouver to Whistler or from Victoria to Nanaimo — in the heart of Treaty 8 territory.

He said consultation with the province around the Site C dam was not executed properly, and there were no substantive discussions of the project’s negative impacts on Treaty Rights.

“They were just informing us of what their decisions were going to be,” he said.

Willson said negotiations with B.C. and BC Hydro were going nowhere and they felt no choice but to go to court.

“If the province did what they were supposed to do and upheld their obligation to the Treaty, the nations wouldn’t have to defend their Treaty Rights all the time,” he said.

“But that’s not what happens. The province and industry push it all the time to see how far they can go, and then First Nations have to push back.”

Brooks said as things are now, provinces and the federal government have a “perverse incentive” to stretch out cases and bury First Nations in paperwork and mounting costs.

Willson said that is exactly what’s happening now in his nation’s legal battle against Site C.

“We’re tied up in court and they’re still building the project,” he said.

The Beaver Lake case could change this dysfunctional dynamic, Brooks said. If provinces and the federal government know they have to foot the bill in cases that meet the requirements (the party is unable to pay, the case has merit and the case is in the public interest), it may give governments incentive to wrap up trials more quickly.

APTN reported Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada and Indigenous Services Canada spent around $30 million per year on litigation between 2011 and 2018.

Between 2012 and 2015, former prime minister Stephen Harper’s Conservative government spent $92.4 million on litigation with Indigenous Peoples. Trudeau’s government actually spent $3.5 million more between 2015 and 2018, for a total of $95.9 million.

Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada told The Narwhal, “the Government of Canada believes that the best way to resolve disputes and address outstanding issues is through dialogue and negotiation.”

Lameman and Brooks said Beaver Lake has proposed negotiations several times, but talks never get off the ground because the parties disagree on what issues are up for discussion.

Khelsilem said negotiations going sideways is often why First Nations wind up in court in the first place. He said judges often agree with First Nations in court, but order the Crown and the nations to return to negotiations, which is “not the relief that nations are looking for.”

“[The courts] recommend that they go back to the table and negotiate. Then six years go by and the nation has to go back to court again and say hey, six years have gone by and they haven’t acted in good faith,” he said.

That’s exactly what happened for Squamish Nation, Tsleil-Waututh and Coldwater, when they successfully argued Canada had not met its duty to consult them on the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion. The Federal Court of Appeal sent Canada back to re-do consultation and the approval process in 2018. One year later, Canada re-approved the project and the First Nations again argued that Canada had not consulted in good faith, but this time, the Federal Court of Appeal dismissed their legal challenge and the Supreme Court denied their appeal.

Near the end of her time as Attorney General in 2019, Jody Wilson-Raybould was mandated by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to write a directive on civil litigation involving Indigenous Peoples, meant to provide guidance to federal prosecutors.

A central objective of the directive is “to advance an approach to litigation that promotes resolution and settlement.”

In the directive, Wilson-Raybould said litigation can be important and necessary in receiving “guidance from the courts” in complex issues.

“However, litigation cannot be the primary forum for achieving reconciliation,” she said. “Where litigation is unavoidable, this directive instructs that Canada’s approach to litigation should be constructive, expeditious and effective in assisting the court to provide direction.”

“In other words, stop delaying and denying,” commented Smitten from RAVEN Trust.

“All the rhetoric we hear nowadays about reconciliation, or that the relationship with Indigenous Peoples is Canada’s most important relationship, and then you compare that to this case — it’s just such a stark contrast,” she said.

Still, she added, courts play an important role as arbiter. Courts can “change things on the ground in a way that’s permanent and leads to upholding of Indigenous Rights in a tangible way,” she said.

“It is slow, but in many cases, it’s worth waiting for.”

Lameman said she hopes both cases will set precedents for Indigenous Rights to be respected, and allow them to defend their rights “without having to choose between drinking clean water and having a home to live in.”

To her, the solution is for the Crown to meet Beaver Lake for negotiations on “equal terms.”

“The solution is full implementation of the treaty,” she said. “Full and equal participation as Treaty partners.”

Updated June 13, 2021 at 9:23 a.m. PT: This article was updated to clarify Crystal Lameman’s title with the Beaver Lake Cree Nation, to note the lawyer she attended court with was the nation’s lawyer and to add in reference to the Beaver Lake Cree Nation’s experience of colonization and genocide.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits