B.C. has a new policy for staking mining claims. Why doesn’t anyone like it?

B.C. previously allowed mineral claims without First Nations consultation. It was court-ordered to fulfill its...

The grizzly bears of Glendale Cove are the stars that draw international visitors to Knight Inlet Lodge. They are also the catalyst for one of the more than 100 successful First Nations businesses launched with the help of Coast Funds, an Indigenous-led conservation finance organization created through the 2006 Great Bear Rainforest agreements.

“It is 100 per cent First Nations owned and it opened up our eyes to opportunities beyond resource extraction and shone a light on the opportunities and benefits of ecotourism,” Dallas Smith, president of Nanwakolas Council and Knight Inlet Lodge, told The Narwhal.

The former fishing lodge was bought two years ago from Dean and Kathy Wyatt by Nanwakolas — representing the Da’naxda’xw Awaetlala, Mamalilikulla, Tlowitsis, Wei Wai Kum and K’omoks First Nations — with a $6-million investment from Coast Funds, which allocates funds across the Indigenous communities of the Great Bear Rainforest and Haida Gwaii.

“It was a fair chunk of change and one of the great things is it has shown First Nations can work together in ecotourism opportunities when we pool our assets and those of Coast Funds,” Smith said.

The success of the ecolodge can be measured in occupancy rates of 90 to 95 per cent, with the majority of visitors coming from markets such as Europe and Australia.

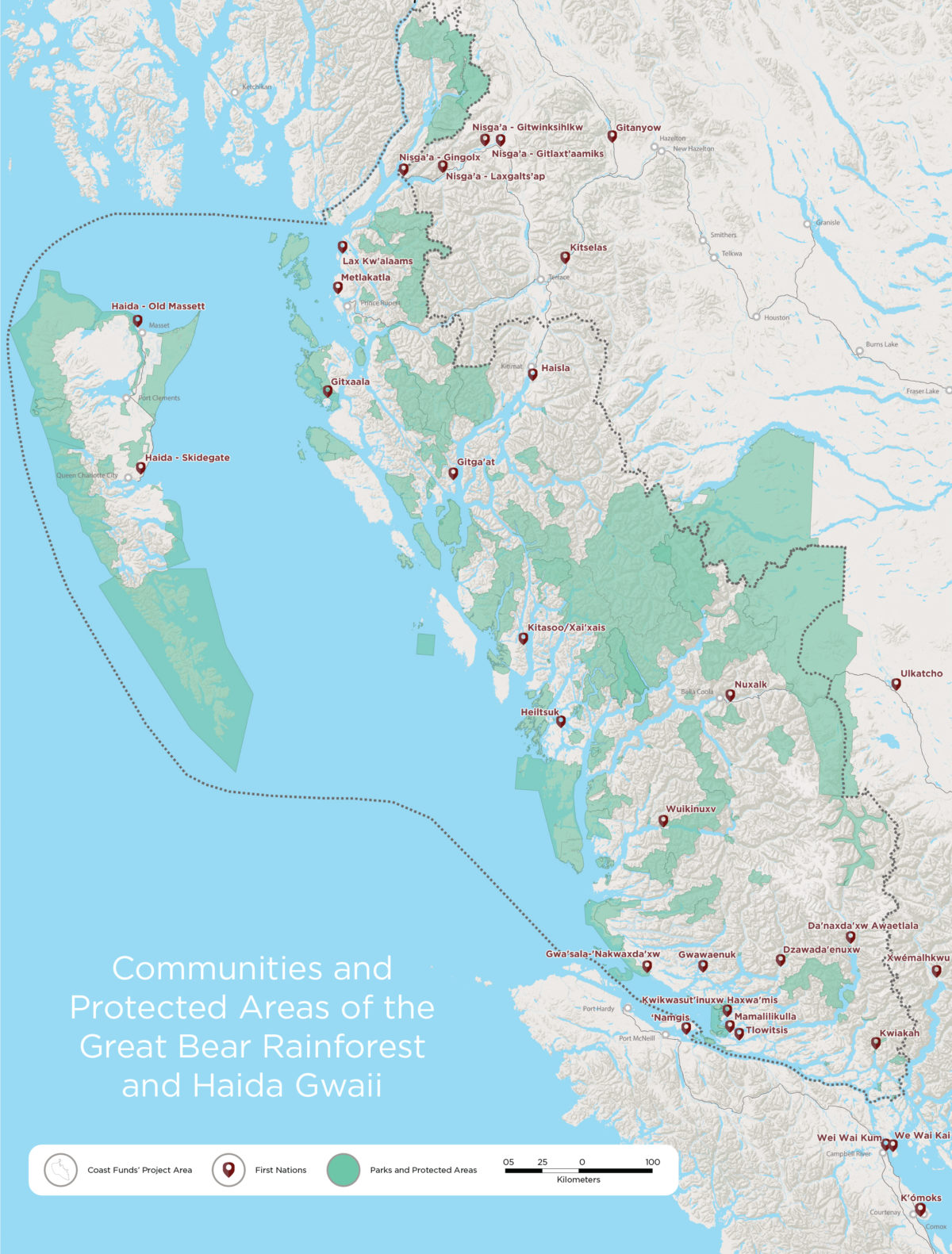

The Great Bear Rainforest covers 6.4 million hectares on British Columbia’s north and central coast — equivalent in size to Ireland. The land is home to 26 First Nations. The 2006 agreements outlined forest practices for the area, including protecting 70 per cent of old-growth forest.

Map: Coast Funds

Coast Funds was established with funding that came through First Nations’ reconciliation agreements with B.C. and Canada, in combination with funding raised through private donations.

In addition to financial help, Coast Funds has provided help with business management and scientific training so community members can learn more about the bears and other wildlife populations.

Knight Inlet Lodge now offers 13 wildlife viewing opportunities with seven bear viewing stands, an array of small boats that take visitors up spawning channels for a closer look at the bears and 52 wildlife cameras — down from 57 as five were destroyed by wolves or bears.

As much effort is put into bear monitoring and gaining a better understanding of bear life cycles, diet and migration routes as is put into offering a good experience for customers, Smith said.

“We make sure that we are not having an impact on bear health and there are not too many boats crowding into the same inlet. You are not even allowed to sneak a cookie into the boat,” Smith said.

Four Guardian Watchmen have been trained for Knight Inlet, with another three in training, and the monitoring program is a model for managing the surrounding territories. Indigenous-led guardian programs empower communities to manage ancestral lands according to traditional laws and values.

Guardian Watchmen are the eyes and ears on the lands and waters of the Great Bear Rainforest. Pictured here are members of the Coastal Stewardship Network — one of the first projects for which Coast Funds’ board approved funding. Photo: Alishia Boulette

Knight Inlet is an example of the achievements of the conservation finance funds, which promote community well-being and Indigenous-led sustainable development and stewardship, Brodie Guy, Coast Funds executive director, told The Narwhal.

Over the last decade, more than 1,000 permanent jobs have been created, 100 businesses have been developed or expanded and 14 regional monitoring and Guardian Watchmen programs, operating across 2.5 million hectares, have been created or expanded, according to a Coast Funds report released this week.

Funding approved for 353 projects has attracted more than $286 million in new investment to the region between 2008 and 2018 and every dollar spent by Coast Funds leverages three or four dollars, according to the report.

“We are demonstrating that conservation finance, led by Indigenous people, is the key to protecting the world’s most precious ecosystems, such as the Great Bear Rainforest and Haida Gwaii,” Guy said.

One key is that funding is allocated across the communities, rather than one big pot, so it avoids the gold rush mentality or competition between First Nations, Guy told The Narwhal.

“It’s completely up to the nation based on their vision for moving forward and their stewardship of the land and water in this period of — hopefully — decolonization,” he said.

Spirit Bear Lodge in Klemtu sponsors the Súa youth cultural program to support cultural reconnection with Kitasoo/Xai’xais traditions. The lodge is owned-and-operated by the Kitasoo/Xai’xais Nation and employs 10 per cent of the local population. Photo: Súa youth cultural program

Fisheries technicians from Lax Kw’alaams Fisheries Stewardship program hold up a red rock crab while conducting Dungeness biosampling as part of surveys occurring year-round in Stumaun Bay and Big Bay. First Nations have conducted 222 species research and habitat restoration initiatives with support from Coast Funds. Photo: Lax Kw’alaams fisheries stewardship program.

Initiatives include more than 220 species research and habitat restoration programs, 71 projects involving access to traditional foods and 50 protecting cultural assets.

The larger projects range from a renovated grocery store in remote Rivers Inlet to a unique sustainable scallop project and, so far, of the more than 100 businesses started or expanded, only four have failed, Guy said.

Most are community owned and the low failure rate demonstrates the strategic, strong and smart leadership of First Nations applying for projects, he said.

“We are moving away from a totally extractive economy with publicly traded companies coming into the Great Bear Rainforest and Haida Gwaii and extracting value and leaving little value there,” Guy said, underlining that a new way of doing business has taken root.

“We are shifting from an extractive and exploitative model of development to one that has benefits for everyone. It’s not just Indigenous people that are benefitting. It’s everyone of the Central Coast,” he said.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

B.C. previously allowed mineral claims without First Nations consultation. It was court-ordered to fulfill its...

British Columbia has vowed to fast-track several mining projects in an effort to blunt the...

Alberta introduced North America’s first industrial carbon tax in 2007. Now an industry email obtained...