Will Canada’s next prime minister support Indigenous Rights and conservation projects?

The Conservative and Liberal parties diverge sharply on Indigenous issues. Here’s what that could mean...

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

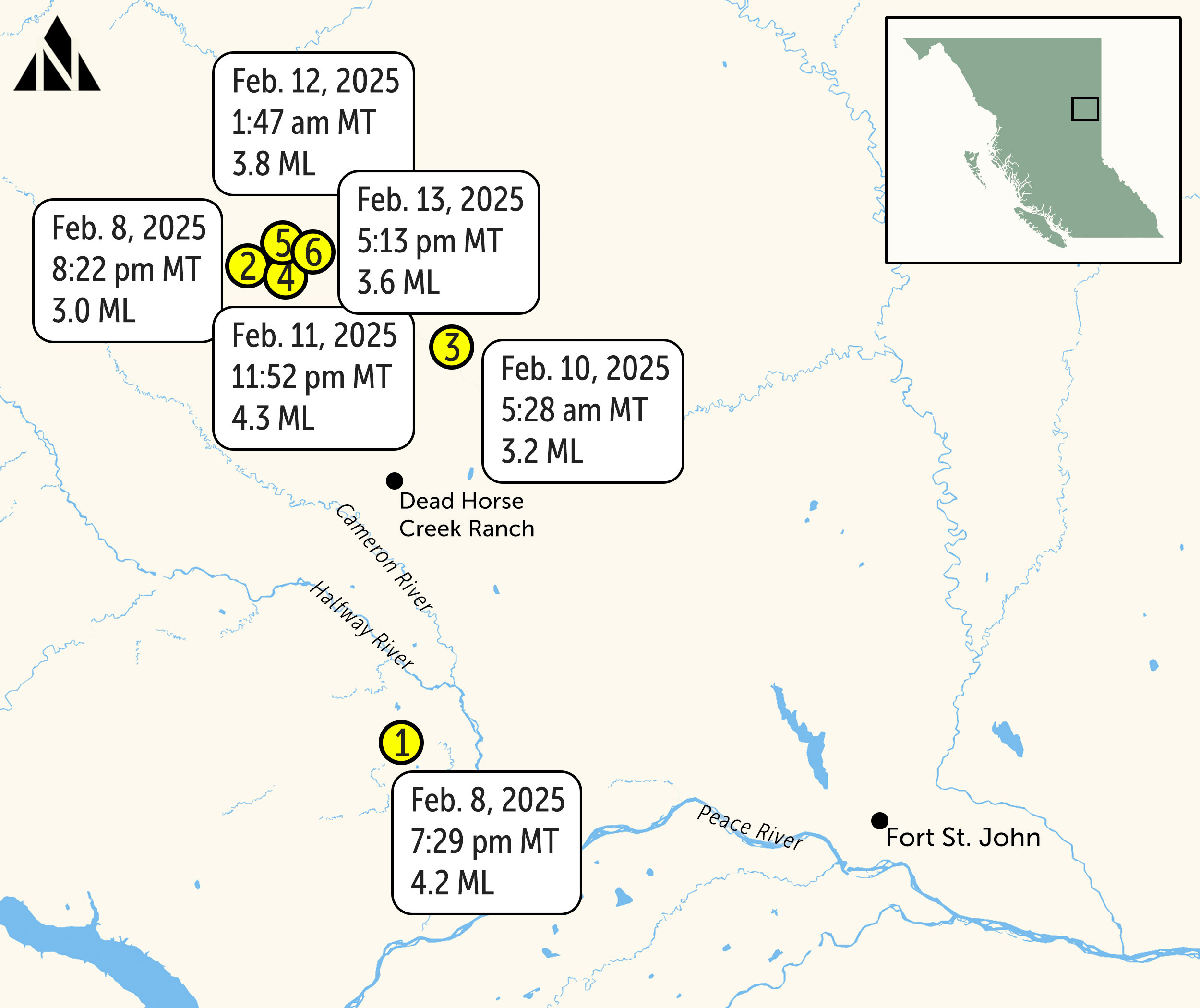

In mid-February, B.C.’s northeast was shaken by a series of earthquakes that both the province’s energy regulator and Natural Resources Canada say were linked to hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, for natural gas.

To release oil or gas from rock formations deep underground, companies blast a mix of water, chemicals and sand into the earth, a process that can sometimes trigger earthquakes.

Honn Kao is a seismologist, or earthquake scientist, who leads a Natural Resources Canada research project on “induced seismicity,” which refers to earthquakes caused by human activities. He says the whole point of hydraulic fracturing is to cause very, very small earthquakes, known as microseismicity, to fracture rock and release gas. “That is totally normal, because that’s the purpose of it.”

“It is not a particular surprise to see induced earthquakes that happened in the area where you have a lot of hydraulic fracturing operations or wastewater disposal injections,” Kao says in an interview. The two, he says, “usually go hand in hand.”

Naturally occurring earthquakes happen when underground rock suddenly breaks and there is motion along a fault. The sudden release of energy causes seismic waves that shake the ground.

When fracking fluids are injected into the earth’s subsurface at high pressure, they sometimes cause faults to slip earlier than they would naturally, inducing an earthquake, Kao explains. “So quite often [when] you have an increased level of hydraulic fracturing operation in the region, then the level of seismicity becomes larger, higher as well.”

But that doesn’t necessarily mean bigger earthquakes will occur. The vast majority, Kao says, are “small events that can be located or detected by seismometres, but not necessarily felt by local residents.”

The issue, Kao says, is when earthquakes are large enough to be felt in nearby communities. “That means the energy released by the earthquake is way bigger than the energy that we input through fluids.” The implication, he says, is that it must have triggered a fault where energy is already building up for an earthquake … “and you just simply make it happen earlier.”

And that has long concerned local residents, from ranchers to people worried about their well-being and drinking water. Some northeast B.C. residents affected by fracking can no longer get earthquake insurance.

Determining if an earthquake is induced by fracking requires investigation and research that includes examining the rock properties where the earthquake occurred and the injection history for nearby fracking operations, Kao explains. An earthquake is generally deemed to be induced if it occurs near an active fracking injection operation, he says.

Injection operations take place at relatively shallow depths, while many natural earthquakes occur at deeper depths. “Generally speaking, most of the induced earthquakes occur at or slightly above the injection depths.” But sometimes they are deeper, so seismologists have to examine different factors to infer whether a quake is caused by industrial activity.

Induced earthquakes usually occur in clusters, like the February earthquakes in B.C.’s northeast, Kao adds. “Once the hydraulic fracturing operations finish, they die down very quickly.”

The BC Energy Regulator requires any fracking operations that trigger an earthquake with a magnitude of 4.0 or greater to immediately suspend operations. In an emailed response to questions, the regulator said the operations may continue with written permission “once the well permit holder has submitted operational changes satisfactory to the BC Energy Regulator to reduce or eliminate the initiation of additional induced seismic events.”

Kao says B.C. hasn’t experienced induced earthquakes large enough to cause significant damage to buildings or infrastructure. Most earthquakes causing damage to buildings and infrastructure have a magnitude of 5.5 on the Richter scale or higher, Kao explains.

That doesn’t mean smaller earthquakes can’t have impacts. A B.C. family says a 4.3 earthquake on Feb. 11 precipitated a rush of calf births on its ranch, including premature twins, and the loss of most of their main water supply. While the quake may not have caused damage to buildings and infrastructure, Kao says “it certainly is a warning sign.”

He says it’s important to make sure a robust regulatory framework is in place that will prevent fracking-induced earthquakes from becoming large enough to cause significant damage in the community. “I think that is really the ultimate balance we want to achieve between public [safety and concerns] and the economic benefit of the industrial activity.”

The regulatory framework appeared to be working in the case of the February earthquakes he says, because they died down once the fracking operations responsible ceased.

Fracking companies can take steps to prevent earthquakes by controlling the number of injection wells or the volume of injected fluids. If an earthquake occurs, Kao says the operator can immediately change the injection pattern by reducing the injection rate, “or even completely shut down their injection operation.”

Kao and other researchers are studying the spate of February earthquakes in northeast B.C.

“We want to figure out why it happened, what we have missed, what kind of sign can we actually see beforehand? And hopefully we’ll build that into the regulatory framework, so that we can prevent these kinds of things … in the future.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. When I visited my reserve, Moose Factory,...

Continue reading

The Conservative and Liberal parties diverge sharply on Indigenous issues. Here’s what that could mean...

After a series of cuts to the once gold-standard legislation, the Doug Ford government is...

The BC Greens say secrecy around BC Energy Regulator compliance and enforcement is ‘completely unacceptable’