In a Nova Scotia research lab, the last hope for an ancient fish species

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...

The enticing smell of cooking salmon filled a clearing in the woods with the sounds of a nearby river singing its late summer song on Gitanyow lax’yip (territory). A crowd of about 150 people gathered in late August — community members, guests from neighbouring nations and non-Indigenous supporters — to celebrate the second anniversary of the creation of Wilp Wii Litsxw Meziadin Indigenous Protected Area.

The fish camp sits above T’aam Mats’iiaadin (Meziadin River), where salmon leap up the falls on the last leg of their long journey to reach spawning grounds in the cold creeks that spill down from glaciated mountains. As the once-abundant spawning channels warmed and the numbers of salmon returning dwindled, Gitanyow fisheries researchers noticed salmon were spawning in new systems — the ones fed with cold water from the ice-covered peaks. Two years ago, tired of waiting on the provincial government to act as populations continued to plummet, the Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs declared the creation of the new protected area under ayookxw, Gitanyow law.

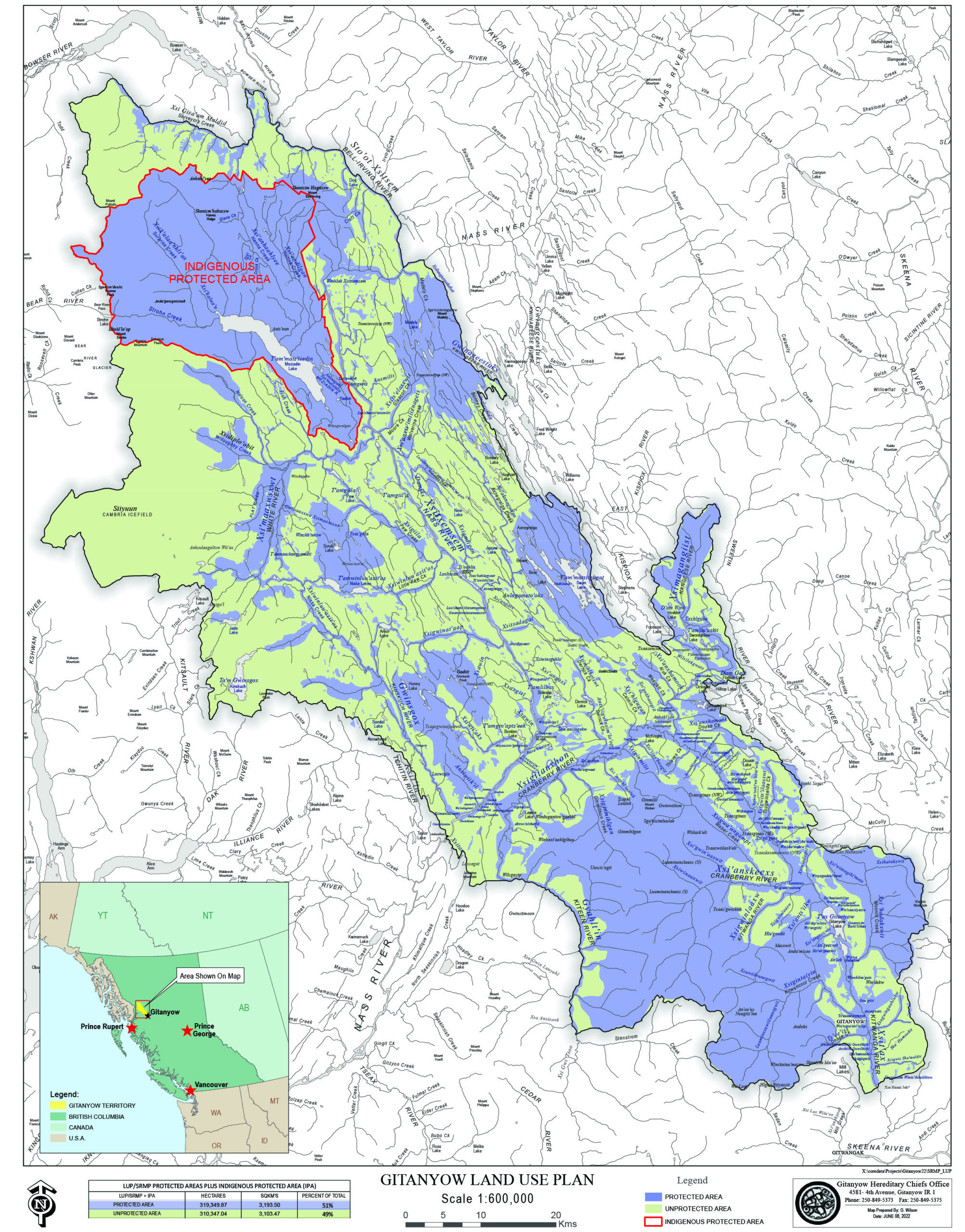

Spanning 54,000 hectares of land and water in northwest British Columbia, it’s a place of abundance, where bears outnumber humans and salmon return in the tens of thousands to spawn every year. It’s also a place where the province has handed out mineral rights to settlers.

When the chiefs signed the declaration in 2021, B.C. was nowhere to be found. Two years later, the province still hasn’t officially recognized the nation’s assertion of its right to protect the area. That means, under colonial laws those mineral interests are still valid, leaving the door open to industrial development in the protected area — and conflict with Gitanyow.

“British Columbia is a little bit slow,” Sk’a’nism Tsa ‘Win’Giit, Joel Starlund, a Gitanyow wing chief, said with a wry smile. “After the [2021] event, they said, ‘Hey, hold up Gitanyow, we’ve seen what you’ve done. We are interested in discussing potentially protecting this underneath British Columbia law as well.’ ”

“A lot of people get scared when they hear ‘traditional laws’,” he continued. “Our ayookxw … has been established for thousands of years — and our hereditary system as well. But that doesn’t mean that that old system is not able to operate in the modern day context.”

In other words, the Gitanyow chiefs are willing to work with the government to bring provincial policies and legislation into alignment with ayookxw — but they’re not going to wait forever. Starlund said discussions about the Indigenous Protected Area have been underway for about a year now and neighbouring Nisga’a Nation is involved in the conversation.

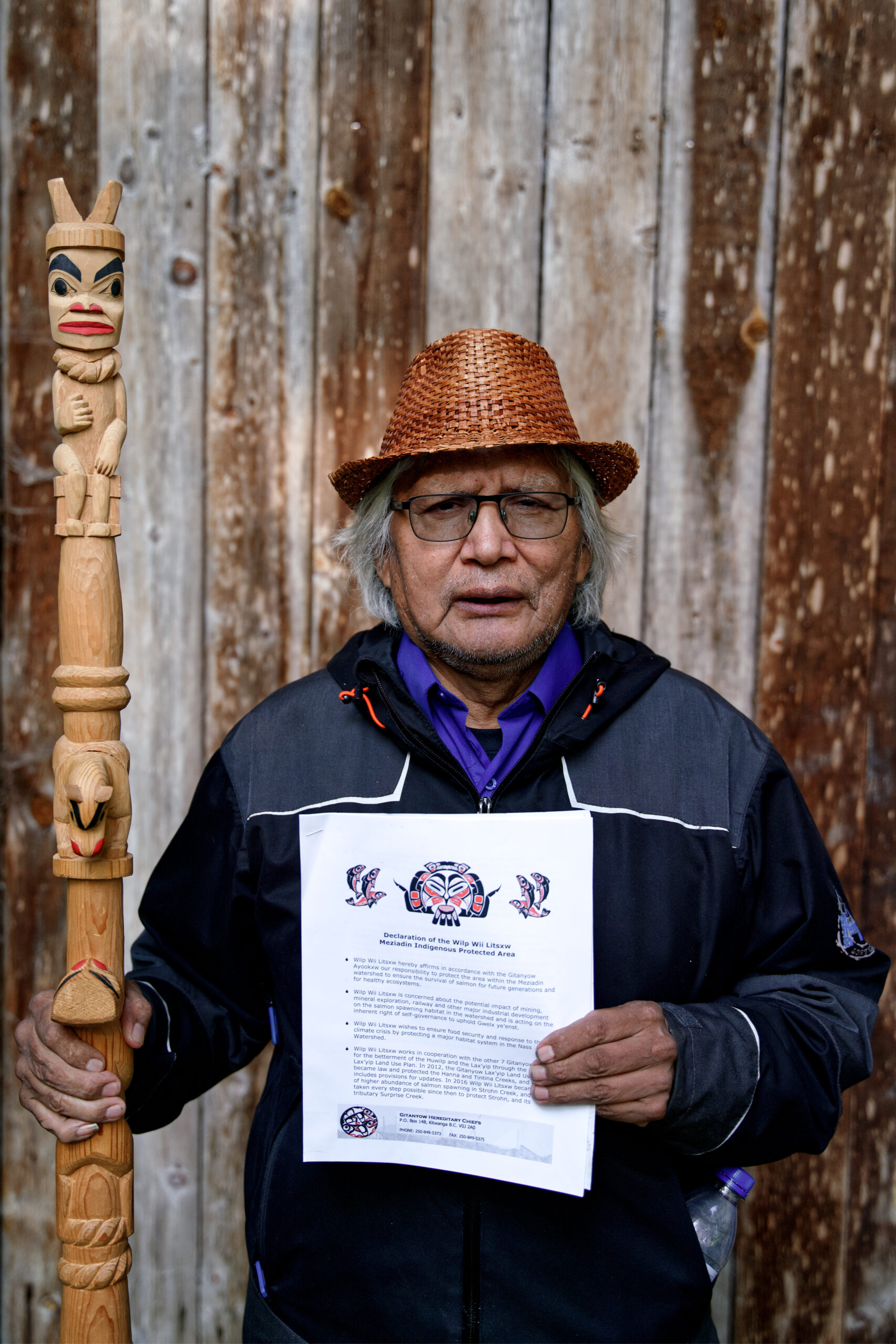

With his grey hair tucked under a braided cedar headband, Simogyet (Chief) Wii Litsxw Gregory Rush Sr. spoke softly. The protected area is on his wilp (house) territory and when the chiefs discussed creating the protected area prior to the 2021 declaration, he gave his blessing.

“I’ve met so many people over my time here thanking me for the work that we are trying to do in protecting this very eco-sensitive area,” Wii Litsxw said, acknowledging the dedication of his fellow chiefs and the next generation of Gitanyow leaders.

“One of the final wishes of my brother, Xlgo’hiss’gethxws, was to have his ashes spread here,” he said. “This is just how special this place is.”

Simogyet Malii Glen Williams, president of the Hereditary Chiefs’ office, said what’s happening now is the culmination of generations of work to reclaim the rights that were stripped away when colonizers first arrived.

“I never forget spending a lot of time with my grandfather,” he told the crowd sheltering from the hot summer sun. “He said, ‘You watch, one day our ayookxw is going to be in the white man’s law. It’ll be a small light. It’ll glow, it’ll flicker … but one day it’ll glitter in their supreme law.”

B.C.’s Mineral Tenure Act is at the heart of the disconnect between Gitanyow ayookxw and colonial law, when it comes to the new protected area.

Currently, anyone with a credit card can easily register an online account with the province and stake claims on First Nations territories without first getting consent. Even if the person or company behind the claim has no plan to conduct any mining activity, a tenure, once granted, throws up a roadblock to any land-use planning or habitat protections. Several nations and supporters have been calling for legal reform for decades, noting the legislation has its origins in the 1800s. B.C. introduced some changes in 2005, creating an online application system which led to a dramatic increase in claims staked on First Nations’ territories. Earlier this year, the Gitxaała Nation was in the B.C. Supreme Court, providing testimony for a challenge filed against the province. Gitxaała, Ehattesaht Nation and numerous supporters argue the current system is in direct conflict with Indigenous Rights.

On Gitanyow lax’yip, that conflict frustrated years of efforts to protect salmon habitat despite ample data showing the fish populations are migrating as climate change advances. Figuring out what to do with existing tenures that overlap with the Meziadin Indigenous Protected Area appears to be a thorny issue for the B.C. government, according to the Gitanyow chiefs.

“That whole new area is covered in mineral tenures that were given to different people that wanted those rights,” Starlund said. “British Columbia would have to compensate those people millions of dollars [but] that doesn’t seem to be the issue. The issue seems that they don’t want to provide uncertainty to the mineral tenure rights-holders.”

In 2022, B.C. Mining Minister Josie Osborne was tasked with modernizing the legislation to bring it into alignment with the principles of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Among the crowd gathered at Lax An Zok were a handful of B.C. government employees, an incremental shift from the notable absence of any provincial representatives in 2021. The Chiefs acknowledged their presence at the celebration.

“At the original event, they were kind of told not to go — so we are making progress,” Starlund noted. “I just want to thank everybody for coming and witnessing.”

The Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation — which employs at least two of the government employees who made the three-hour drive up from Smithers — forwarded The Narwhal’s request for an interview to the province’s Ministry of Water, Lands and Resource Stewardship.

Nathan Cullen, the minister who leads this department, was not available for an interview but said the province is working with Gitanyow on land-use planning and relationship-building between nations.

“B.C. is committed to Indigenous-led land stewardship and recognizes Gitanyow’s work to advance their vision for the Meziadin area,” he told The Narwhal in an emailed statement.

Gitanyow’s approach to enforcing ayookxw and charting a path forward from the ongoing impacts of colonization is a model of patience and diplomacy. The new protected area is one example of several showcasing the nation’s work to uphold gwelx ye’enst — the rights and responsibilities to sustainably pass on the land from one generation to the next. In late 2022, Gitanyow and B.C. celebrated the 10th anniversary of a groundbreaking land-use plan, which sets parameters for how, where and when industry can operate on the lax’yip.

“Everybody’s been following that Gitanyow land-use plan,” Starlund said. “The sky hasn’t fallen, there hasn’t been uncertainty and the stock market hasn’t crashed, like a lot of British Columbia government members would have been telling you about 10 to 15 years ago.”

Naxginkw, Tara Marsden, a Gitanyow member from Wilp Gamlakyeltxw who has worked with the Chiefs for many years, said the relationship with the province isn’t the only one that matters. Working closely with industry operators enabled Gitanyow to ensure protection of the most vulnerable areas while also creating opportunities for community members.

She gave a shout-out to ArcWest, a Vancouver-based mineral exploration company.

“They sent us a letter saying, ‘We will respect the Gitanyow Indigenous Protected Area, we will not go mining in there.’ ”

Another company from the Vancouver area, P2 Gold, similarly agreed not to pursue its mineral interests in the area.

“We’re trying to be good neighbours and work together up in the area,” Joe Ovsenek, president of P2 Gold, told The Narwhal in a previous interview.

“There are companies that are not listening to us or not respecting us,” Marsden added. “So we need to acknowledge and shine a light on those people who are doing the good thing, who are respecting the environment and respecting Indigenous Rights.”

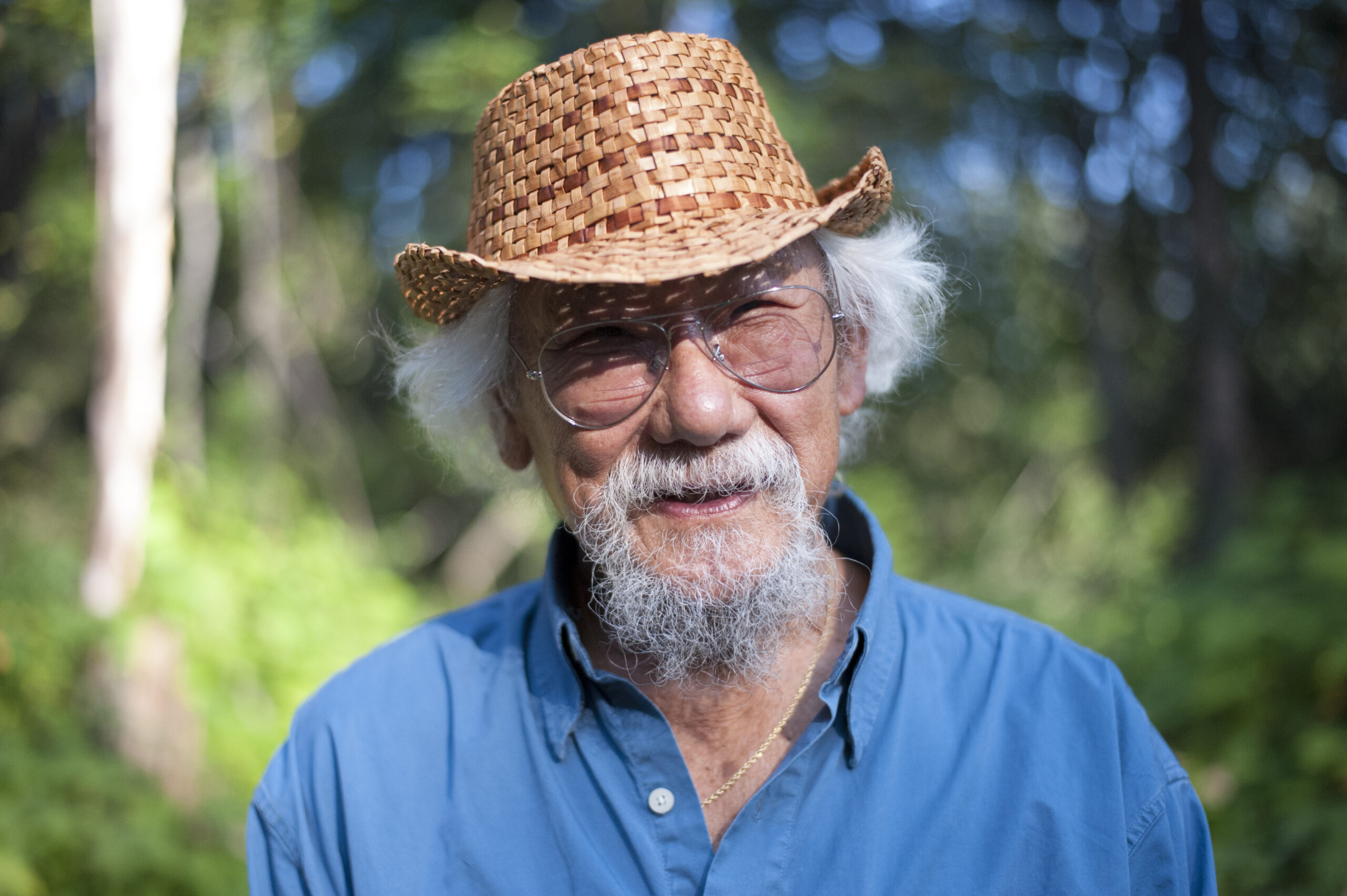

To celebrate the second anniversary of the Indigenous Protected Area, the Gitanyow chiefs welcomed environmental icon and climate activist David Suzuki and his wife, Tara Cullis, to the lax’yip. Wearing a blue denim shirt tucked into his jeans, with a knife strapped to his belt, Suzuki spoke with familiar frankness.

“We’re talking about the protection of an area that is our life source,” he said. “Why do we give a shit what the economy is going to do as a result? That’s our highest priority? Let’s make the economy somehow fit the most important things.”

His speech somehow spanned the entirety of human history, highlighting key moments when our species started to wreak havoc on the planet and pointing out where we went wrong.

“We lived in a world where we understood we lived in a web — a web of interconnections, a web of relationships with all other animal species that we called our relatives, with all plant species, with air, water, soil and sunlight. That has been the understanding of our species for over 95 per cent of our existence.”

The last five per cent, he said, is when we shifted our perspective away from seeing ourselves as part of the natural world.

“The way that we look at the world shapes the way that we behave and act towards that world,” he explained, adding Gitanyow’s actions reflect a sustainable worldview — one that everyone can learn from.

“Indigenous people have to take ownership. Take back what is rightfully yours and allow us then, through the kinds of values and principles that you’ve received from your Elders, to begin to treat the world in the manner that it should be.”

Starlund said the first responsibility of members of the nation is upholding ayookwx — but that doesn’t mean shutting out the colonial government.

“Both of our laws are coming together to make sure that the territory is going to be able to be passed down to future generations,” he said.

At the fish camp, children of all ages are part of all the proceedings. Standing patiently with their parents and aunties and uncles, snacking on jello and carrot cake, playing and giggling at the edges of the clearing. A grandmother rocked a baby in her arms as wilp members stood behind their Chief and held a moment of silence for those who passed away this year.

Simogyet Malii said he thinks often about what to do with all the information being gathered about fish and wildlife, habitat and climate. He hinted at a coming court case but said the knowledge will also be passed down.

“I totally believe that continuing to move forward, we begin to sort this information out, build it into our schools, into the elementary schools, into the secondary schools,” he paused, as if listening to his grandfather’s words again. “Develop courses in ayookwx, our own ayookwx, and use the territory as a classroom: that’s the future.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...

From investigative reporting to stunning photography, we’ve been recognized with four 2024 CAJ Awards nods...

The Narwhal is expanding its reach on video platforms like YouTube and TikTok. First up?...