In a Nova Scotia research lab, the last hope for an ancient fish species

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...

Teck’s plan to sell its Elk Valley coal mines to Swiss mining giant Glencore has raised alarm bells on both sides of the Canada-U.S. border amid negotiations over an international inquiry into extensive water contamination from the mines.

The sale “introduces huge uncertainty into a very alarming situation,” Tom McDonald, chairman of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, said in a statement to The Narwhal. “Glencore’s record is really concerning.”

Teck’s proposed sale of its coal mines is subject to review under the Investment Canada Act. But if the $9-billion deal goes through as planned, Glencore would take a 77-per-cent stake in the mines, while Japan’s Nippon Steel Corporation and South Korea’s POSCO, another steel-making company, would gain a 20-per-cent and a three-per-cent stake in the mines respectively.

In a statement announcing the deal last week, Glencore CEO Gary Nagle said the company “has high regard for the business that has been developed over many decades in British Columbia and looks forward to maintaining and enhancing its operational performance, environmental stewardship and social contribution.”

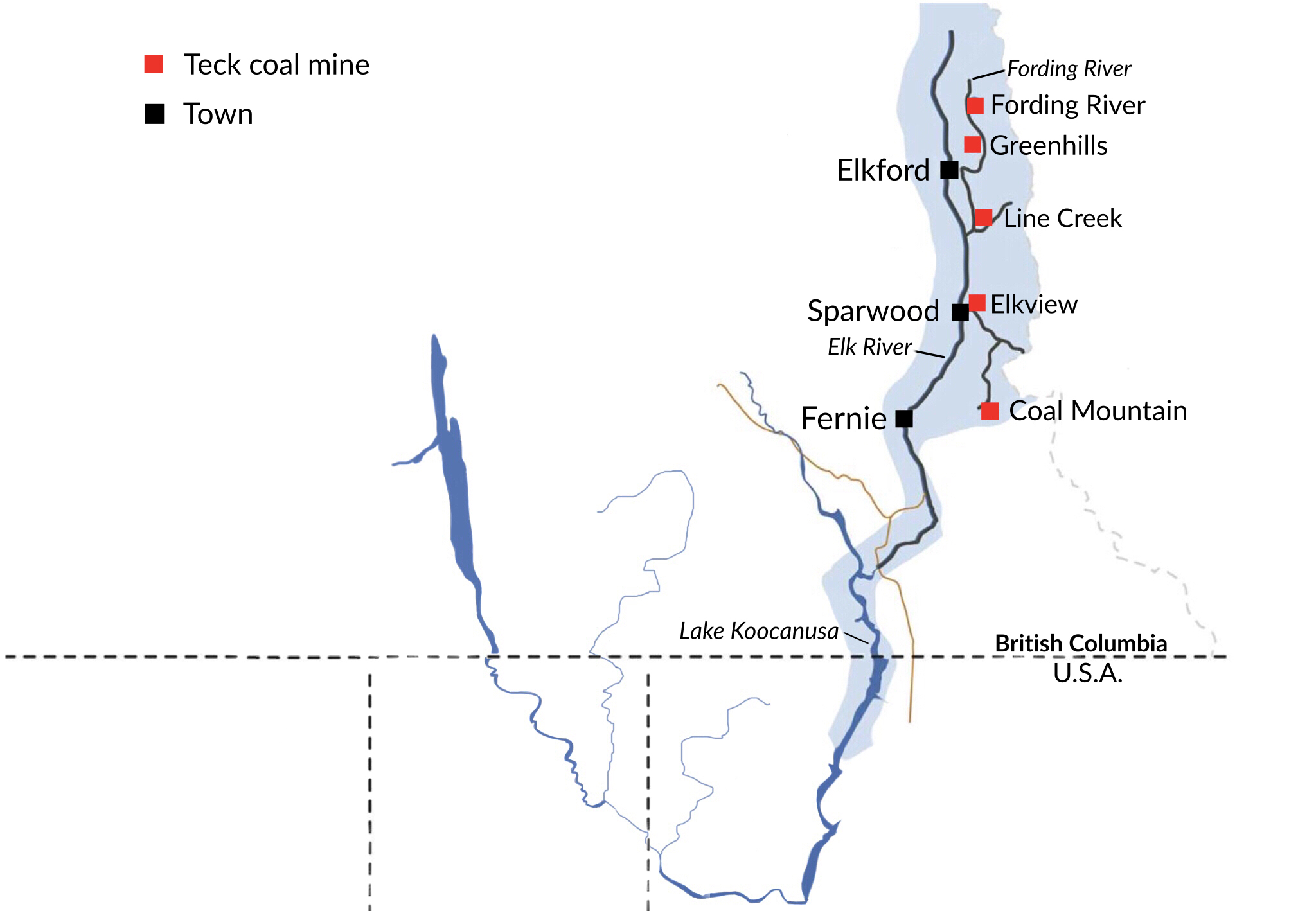

Coal has been mined from the Rocky Mountains in the Elk Valley for more than 120 years and remains a significant economic engine both regionally and provincially. Teck’s coal business is the largest employer in the Elk Valley. It contributed an estimated $4.9 billion to B.C.’s GDP in 2019, accounting for roughly 59 per cent of B.C. mining sector GDP, according to an economic contribution report prepared for the company by Deloitte.

But as coal mining expanded, so has the pollution that now courses through Ktunaxa Nation territory. The nation, whose territory spans parts of B.C., Montana and Idaho, includes the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes in Montana, the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho and four First Nations in B.C.

To access the coal, Teck systematically blasts into the mountaintops where it operates. The process produces an enormous amount of leftover waste rock.

When that rock is exposed to rain and snowmelt, contaminants, such as selenium, leach into the water and find their way into nearby rivers and creeks, eventually flowing into the Koocanusa Reservoir and across the U.S. border.

The contamination has raised particular concerns for at-risk westslope cutthroat trout and, farther downstream, white sturgeon and burbot. In fish, too much selenium can impede reproduction and cause deformities such as curved spines, misshapen skulls and abnormal gills.

Teck has invested more than $1.4 billion in water treatment and other measures and spokesperson Chris Stannell said the company is “improving water quality in the region.”

But pollution concentrations in some areas downstream of the mines remain far higher than the levels the B.C. government considers protective of aquatic life.

If Glencore’s bid for the Elk Valley coal mines is approved under the Investment Canada Act, the Swiss miner will be walking into a long-simmering international dispute over this pollution.

For more than a decade, the Ktunaxa Nation has pushed Canada and the U.S. to refer the transboundary contamination to the International Joint Commission. The commission was created under the 1909 Boundary Waters Treaty to study and recommend solutions to intractable disputes and many believe it has an obvious role to play in this case.

In March, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and U.S. President Joe Biden said they intended to reach an agreement in principle to address the pollution by the summer, but that deadline came and went with no announcement.

With negotiations ongoing, McDonald said Teck’s plan to sell the mines only adds urgency to calls for the International Joint Commission’s involvement. “The future of our waters depends on it,” he said.

A spokesperson for Glencore declined to comment when asked for the company’s position on an International Joint Commission reference.

In his public statement last week, Nagle said Glencore is committed to ensuring the deal benefits Canada and noted the company has made specific commitments related to jobs, reclamation and meaningful engagement with Indigenous Nations.

The company also specifically said it would continue to implement the Elk Valley Water Quality Plan, a government-approved plan outlining Teck’s targets and strategy for improving water quality, and continue related investments in research and development.

On Wednesday, Yaq̓it ʔa·knuqⱡi ‘it Nasuʔkin Heidi Gravelle met with representatives from Glencore and Teck, including Nagle.

In an interview with The Narwhal after the meeting, Gravelle said, “It speaks volumes” that the company took time to meet face-to-face.

She said her biggest concern is what the change in ownership will mean for the land, water and all living things.

“There are mountains that have been fully removed and decimated that our ancestors once walked on,” she said. “There’s no other way to describe it other than mass devastation.”

“What’s been done in the past has been done. We can’t rewrite it, we can’t change it. But we can change what we do from this day going forward,” she said.

Gravelle said she was clear with Glencore that the harms wrought by decades of mining must be repaired, that there must be “reconciliation with the land,” and Yaq̓it ʔa·knuqⱡi ‘it must be involved in decisions about what happens within the nation’s territory.

“Will Glencore meet the expectations that we will not stray from?” she asked. “We don’t know that yet.”

But Gravelle said the company’s response was “very positive” and she wants “to remain hopeful that this can be an opportunity to change the way mining is being done.”

But in the context of the unresolved transboundary pollution, there are some concerns about Glencore’s record.

Last year, Glencore pleaded guilty to bribery and market manipulation charges and agreed to pay more than $1.1 billion in penalties. The bribery charges related to payments made approximately between 2007 and 2018 in what the U.S. Department of Justice described as a “decade-long scheme by Glencore and its subsidiaries to make and conceal corrupt payments and bribes through intermediaries for the benefit of foreign officials across multiple countries.”

Glencore also pleaded guilty to a “multi-year scheme to manipulate fuel oil prices at two of the busiest commercial shipping ports in the U.S.,” which took place between 2011 and 2019, the Department of Justice explained in the news release.

In a statement to The Narwhal, Glencore spokesperson Charles Watenphul said the company “has taken significant action over the last several years towards implementing a world-class ethics and compliance program.”

“Glencore is a different company today and is committed to being a company that creates value for all stakeholders by operating transparently under a well-defined set of values, with openness and integrity at the forefront,” he said.

The company has also faced criticism over its human rights record.

Earlier this year, the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre reported 70 allegations of human rights abuses against mining projects Glencore was involved with between 2010 and 2022, including the bribery and market manipulation charges for which the company was penalized last year, environmental impacts and allegations of poor working conditions.

Watenphul told The Narwhal Glencore’s “assets are located in diverse contexts, some in highly developed countries with strong legal and political frameworks, and others in more challenging socio-political circumstances with a history of conflict, limited basic services and weak rule of law. We require our industrial assets to adopt an inclusive community approach informed by the local context.”

“We aim to respect human rights and seek to learn about the traditions, cultures, perspectives and development priorities of people with whom we engage, to build trusting and constructive long-term relationships and to contribute to the social and economic development of affected people and society more widely,” he said.

Watenphul went on to add that “we recognise and uphold the rights of our workforce to a safe workplace, freedom of association, collective representation, collective bargaining, fair compensation, job security and development opportunities.”

In Montana, McDonald raised concerns around the cleanup of a major contaminated site at an old aluminum plant, owned by the Columbia Falls Aluminum Company, which Glencore acquired in 1999.

“They have resisted removing toxic aluminum plant waste and adequately cleaning up that site,” he said.

Watenphul said the Columbia Falls Aluminum Company demolished buildings on site and has worked with government agencies to assess the site and identify options for remediation.

The company “conducted significant investigations at the site with over 1,000 soil samples, 400 groundwater samples, 200 surface water samples, 100 off-site samples and 70 sediment samples to thoroughly evaluate the issues,” Watenphul said.

The Columbia Falls Aluminum Company will continue to work with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Montana’s Department of Environmental Quality “to fulfill its obligations to the community and under applicable law” and “Glencore will continue to ensure the [company] has the resources it needs to meet its obligations,” he said.

Meanwhile, in Quebec, the provincial government is planning to spend $88.3 million to support the relocation of some 200 families that currently live in an area contaminated by a local copper smelter, owned by Glencore, CBC reported in March.

Watenphul said “the expansion of the buffer zone between the 100-year-old smelter and the community is an initiative of the Québec government that Glencore supports.”

“This urban planning project is in addition to our long-term plan to upgrade the facility with the latest technology and to further reduce the smelter’s environmental footprint. Glencore has committed [$500 million CAD] to this project,” he said.

In B.C., the most recent report by the chief inspector of mines shows Glencore owes about $8.5 million in security payments to cover the estimated reclamation liability at three of its closed mines.

Watenphul said “every year each site calculates the estimated cost for its reclamation and discloses this to the government of British Columbia in the annual reclamation report.” He explained that the recent estimate to reclaim three of the company’s four closed mine sites in B.C. are higher than what was included in Glencore’s mine permits. The B.C. government has asked the company to pay the difference by the end of March and Watenphul said the security payments will be made.

He added Glencore will ensure the Elk Valley mines comply with any reclamation security requirements should the sale go through.

Despite the list of commitments Glencore has made regarding the Elk Valley mines, Randal Macnair, the Elk Valley conservation co-ordinator with the Kootenay-based organization Wildsight, remains concerned about the deal.

“Actions speak louder than words and Glencore’s actions don’t give us a warm, fuzzy feeling about their operations,” he said. Instead, it’s “warning bell after warning bell.”

“We’ve got one of the most significant environmental issues in mining in Canadian history on our doorstep and it’s something that needs to be treated with a great deal of respect,” he said.

Selenium concentrations in the Elk River, not far from where it flows into Koocanusa, increased by 551 per cent between 1985 and 2022, according to a new study by scientists with the United States Geological Survey. In 2022, the average selenium concentration at this spot, which is 80-to-120 kilometres downstream of the mines, was 5.77 parts per billion.

Closer to the mines, selenium levels are considerably higher.

B.C’s water quality guidelines recommend average selenium concentrations over 30 days should be no more than two parts per billion. But the province does not require Teck to meet those guidelines in the Elk and Fording rivers.

Instead the provincial government has set much higher regulatory limits — ranging from a monthly average of 19 to 63 parts per billion — that the company is required to meet at certain compliance points downstream of its mines.

Selenium concentrations regularly exceed those limits as well. In the first half of this year, Teck failed to meet the terms of its permits at at least one compliance point in February, March and April, according to the B.C. government’s Elk Valley Water Quality Hub.

Downstream, selenium concentrations at the international boundary in the Koocanusa Reservoir are also consistently higher than the U.S. regulatory standard for the reservoir, which is 0.8 parts per billion.

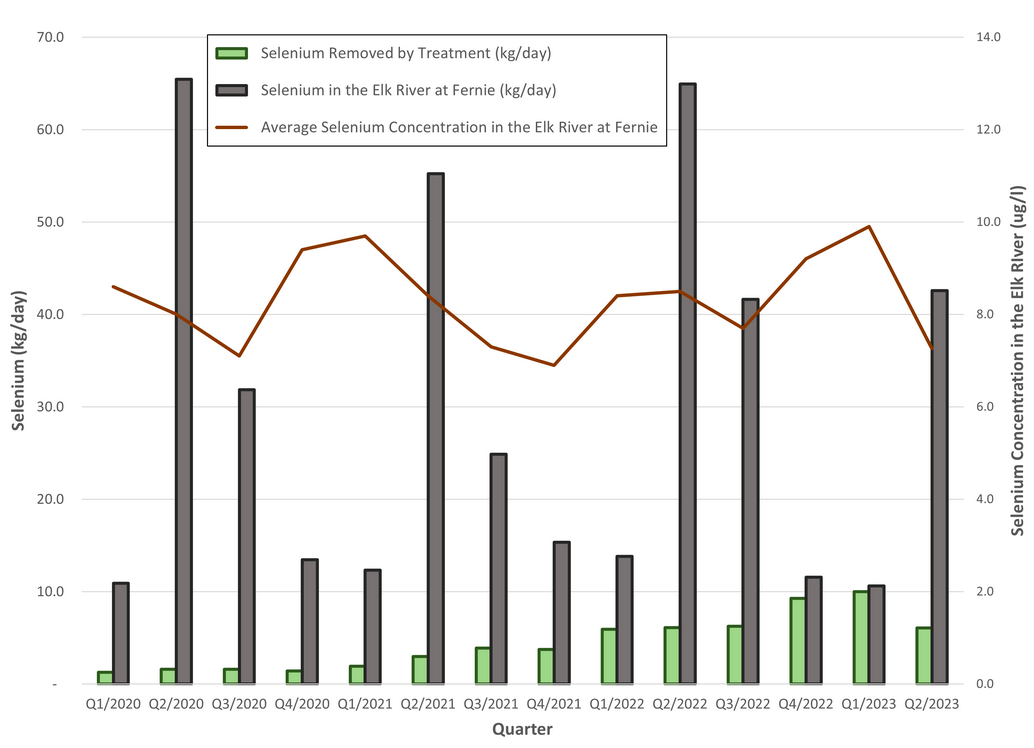

In a statement to The Narwhal, Stannell said Teck’s treatment plants are removing between 95 and 99 per cent of selenium from the water they treat.

“We have constructed four water treatment facilities to date with capacity to treat 77.5 million litres [77,500 cubic metres] of water per day, a four-fold increase from treatment capacity in 2020,” Stannell said. The company expects to increase treatment capacity to 150,000 cubic metres a day by 2026.

But the latest data posted to the Elk Valley Water Quality Hub shows the company continues to face challenges with its treatment facilities.

Between April and June of this year, for instance, Teck had capacity to treat 47,500 cubic metres a day, but was on average treating 24,480 cubic metres per day, due to a number of shutdowns. And, the majority of both selenium and nitrate pollution from the mines was still flowing downstream without any treatment at all.

In a statement to The Narwhal, a spokesperson for B.C.’s Environment Ministry said, “B.C. is continuing to use Teck’s Environmental Management Act permit to ensure that treatment facilities are constructed, and other measures are put in place to further improve water quality in accordance with the Elk Valley Water Quality Plan.”

The province is also committed to updating both the water management plan and the selenium limits for the Canadian side of the Koocanusa Reservoir.

But “given current and planned mine operations and water treatment, it is unclear whether current and planned surface water treatment will be sufficient to meet downstream water-quality regulations,” the U.S. Geological Survey study concludes.

“The treatment plants that they have in place can only treat a certain volume of water in a 24-hour period,” explained Meryl Storb, a hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey and lead author of the new study.

During low flow periods in the winter, Teck can treat a higher proportion of the water coming out of the mines — and because the pollution is more concentrated, the treatment plants are also able to remove proportionally more of the contamination.

But the largest amount of selenium by mass flows into the Koocanusa Reservoir during the spring melt. “All of a sudden you have this huge volume of water, but we still have the same amount going through the treatment plant,” Storb said. So, proportionally, the treatment has much less of an effect.

What that means for contaminant concentrations in Koocanusa and farther downstream depends on how the pollution is mixed through the reservoir over the course of the year, Storb explained.

Erin Sexton, a senior research scientist with the University of Montana’s Flathead Lake biological research station, said, “the report shows that Teck’s mitigations are not working at the scale of the watershed.”

“We have this enormous problem that has gone unaddressed for decades now,” she said.

“There’s been a demand for meaningful action to address the pollution in the river and start to heal the watershed for a very long time, and a reference to the International Joint Commission to set up a multi-government framework to address this problem would be a very significant step forward,” she said.

Discussions between Canada, the U.S. and Ktunaxa Nation governments are ongoing.

In a statement, a spokesperson for Global Affairs Canada said, “Our priority remains to continue to work with the U.S. and other partners in the region to find an appropriate path forward on the issue of protecting freshwater resources in the Elk-Kootenay watershed.”

Sexton said she was cautiously optimistic following a recent meeting in Cranbrook, B.C. But, “we are still waiting for both Canada and the U.S. to make good on their promise,” she said.

After years of discussions, the prospect of the U.S. moving alone to involve the International Joint Commission is being raised once again.

As reported by the Missoulian, Montana Senator Jon Tester called the failure to meet Trudeau and Biden’s end of summer deadline “disappointing” in a letter to Secretary of State Anthony Blinken earlier this month.

“The selenium contamination issues only continue to compound in northwest Montana, and we can no longer delay a solution,” he wrote.

“I urge you to work with Canada to pursue a joint reference to the [International Joint Commission], but to move forward with a unilateral reference if Canada remains unwilling to meaningfully engage on this issue,” he said.

“Our clean water is too important to sit by idly while Canada fails to uphold its end of the agreement.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...

From investigative reporting to stunning photography, we’ve been recognized with four 2024 CAJ Awards nods...

The Narwhal is expanding its reach on video platforms like YouTube and TikTok. First up?...