The Narwhal’s in-depth environmental reporting earns 11 national award nominations

From disappearing ice roads to reappearing buffalo, our stories explained the wonder and challenges of...

November nights in Grand Forks are dipping below freezing, so Courtnay and Jesse Redding are racing the clock as they hustle to transform a 12-by-16-foot shed into a home where they and their dogs can survive the winter.

“We had a building down in our farmyard that was insulated and had power. It flooded quite badly, but we gutted it, put it on skids and moved it up to the high ground on our property,” Courtnay Redding told The Narwhal.

“Yes, it’s small. We won’t have a door on the toilet, but we love each other and we live outside most of the time,” she laughed.

Like many others in Grand Forks, the couple is continuing to struggle with the aftermath of devastating May floods that saw the Kettle and Granby Rivers burst their banks, swamping entire neighbourhoods and the downtown core.

Courtnay Redding walks toward her now-condemned home, on the outskirts of Grand Forks. The house flooded during the past two spring runoffs and has severe water damage and mould. The Reddings are currently renovating a 12 by 16 foot shed to live in for the winter but will continue to use their old home as a workspace and for showering. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Their riverfront dream farm was destroyed, their meat chickens died of shock after being carried out in the middle of the night through armpit-high water, kilometres of fencing was wiped out and, despite an estimated replacement cost of $450,000, insurance claims have been denied and help from the provincial Disaster Financial Assistance is likely to top out at about $10,000.

“Not enough to even cover a new foundation,” said Redding, who is planning to build a new house on higher ground because, like others in the community, she is convinced that the historic flood was not a one-off.

Courtnay Redding walks down to their river front property. This was one aspect of the land that drew them in and they still love the natural beauty the river provides despite the difficulties that come with living next to its volatile banks. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Courtnay Redding stands in her soon-to-be new home — a 12 by 16 foot shed that will serve as a house until they can afford to build a new one on the portion of their property that’s on higher ground. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Jesse Redding stands on the sandy banks of the Kettle River where flood waters once churned. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Jesse Redding shows where the high water mark was this spring when flood waters covered much of his property for the second year in a row. When the Reddings purchased the property in the winter of 2017 the previous owner told them it had never flooded, which they later discovered was untrue. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

In 2017 there was localized flooding in Grand Forks, but nothing prepared the 4,200 residents for this spring’s water levels, which rose more than half a metre higher than previously recorded.

As residents look for answers, there are increasingly pointed questions about the role of forestry and over-harvesting in the watershed.

Six months after the water swept through Grand Forks, at least 28 downtown businesses are still closed and the city is planning to buy between 80 and 120 properties in flood plain areas, at a cost of $60-million to $90-million, if it can get financial support from the federal and provincial governments. The city is also planning to build three new dykes, raise some houses and reinforce several kilometres of riverbank.

A closed cafe in downtown Grand Forks, where 28 business still remain unopened six months after flood waters flowed through the streets. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

The reflection of a closed shop on Second Street is seen in the boarded windows of another. Slow insurance claim processes and extensive water damage have made it difficult for some businesses to reopen. Graham Watt, flood recovery manager at the Regional District of Kootenay Boundary, said he expects some businesses will remain permanently closed. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

A closed hair studio in downtown Grand Forks hosts an advertisement for flood restoration services. Despite more than six months elapsing since water flowed through the streets, many business remained shuttered. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

A recently built house on the outskirts of Grand Forks. Its foundations buckled when the Kettle River rose over its banks in the spring of 2018. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

The financial toll includes about $25 million in response costs, about $26 million in business losses, the loss of a tourist season at a cost of about $30 million and household damages in the $10 million to $20 million range.

“It was a very, very expensive flood and we are looking for permanent solutions. How do we make sure this doesn’t happen again?” Graham Watt, flood recovery manager at the Regional District of Kootenay Boundary, told The Narwhal.

A provincial household emergency assistance program is helping some repair their homes sufficiently to get them through the winter, but about a dozen families need emergency winter housing and will be put up in hotels until they get on their feet, Watt said.

Among the 28 closed businesses, some are unlikely to re-open, he said.

“There are also the farms and rural businesses that had assets in the flood plain, such as large nurseries, which were heavily impacted by the floods, but there is very, very little help for farms,” Watt said.

Graham Watt, recovery manager for the City of Grand Forks, points to one of the many places the now-drought-stricken Kettle River overflowed its banks in the spring of 2018. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

The Kettle River winds through the Grand Forks valley north of the city after the “the forks” where the Granby River joins its waters. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

A house in South Ruckle, one the Grand Forks neighbourhoods most affected by the spring flood, was spared falling into the Kettle River this year. A small shed adjacent to it wasn’t so lucky. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

The Kettle River, which is currently suffering through a drought, winds peacefully through the Grand Forks valley. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Spinoff problems include a shrinking tax base “so those left behind will have a tougher go,” said Les Johnson, whose partner, Lorraine Davies-Van Boeyen, has not yet been able to reopen her downtown business supply store, meaning estimated losses of between $70,000 and $80,000.

Johnson, searching for new ways to put Grand Forks back in business, has taken drone footage of the neighbourhoods that will be abandoned, in hopes he might pique some interest from movie producers.

But, overshadowing all the efforts, are fears that the floods will be repeated next spring and that protective measures will not be in place in time, he said.

As bewildered residents look for causes of the devastation, the provincial explanation

is that a heavy snowpack in the Boundary region, estimated at 238 per cent of the norm, was followed by unusually warm weather and days of heavy rain, resulting in a rapid melt.

“This was an extreme and unprecedented flood event that was affected by a combination of warm weather and rain on an extreme spring snowpack,” said a forests ministry spokeswoman.

No one doubts that the weather created the perfect, flood-creating storm, but there is cause for concern that forestry practices in the watershed, combined with climate change, make future floods a virtual certainty.

Interfor’s lumberyard across the Kettle River from downtown Grand Forks. Some residents believe that dykes built to protect the forestry giant’s property made flooding worse for neighbouring communities because the water had nowhere else to go. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Courtnay and Jesse Redding, who both grew up in Grand Forks and moved back two years ago, draw on decades of local knowledge to come to the conclusion that clearcuts worsened the spring floods.

Jesse, who worked in the logging industry for 20 years, said he is shocked by forestry practices and the size of clearcuts he witnessed in the watershed.

“We think it’s climate change, clearcutting and watershed issues that have caused the flooding. That was not an abnormal winter or spring at all,” Courtnay said.

Courtnay Redding points to future garlic fields, planted on a portion of their property that sits well above the flood plain. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

The Reddings are convinced that the floods will happen again and are ensuring that any new structures and animal pens are built on higher ground, leaving the river frontage as a beach.

Jennifer Houghton, a local realtor and yoga teacher, watched her home flood two years in a row and she is also convinced that the floods were not a weather-related anomaly.

“Last year I had two feet of water in my house and this year I had four feet,” she said.

Houghton has gutted her house, but she’s not taking any chances and, with the help of friends, is building a 230 square foot house on wheels, framed on a commercial trailer.

“I am building a tiny house on wheels because I am 100 per cent sure there’s going to be more flooding because of the logging…The next time the flood comes I can just wheel it out,” said Houghton, who is filming a documentary about the flood.

Grand Forks resident Jennifer Houghton in her unfinished tiny home. She hopes to move in by mid-December with her two dogs. Believing her main house, which has flooded in both of the past two years, will inevitably flood again she decided to invest in a home that can be moved when the water rises in the spring. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Jennifer Houghton on the steps of her unfinished tiny home with her two dogs. Houghton was the first Grand Forks resident to apply for a new tiny home permit approved by the city late last year. She plans to move her new home if floods threaten her property again in the future. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Graham Watt, recovery manager for Grand Forks, looks out over the Kettle River from a bank in the Grand Forks neighbourhood of South Ruckle. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Houghton started researching local history for the documentary, following river and snowpack levels and looking for reasons for the floods. She rapidly zeroed in on the combination of clearcut logging and climate change.

“What’s happening in Grand Forks is a microcosm of what is happening everywhere,” said Houghton, who believes that as people realize how climate change and logging practices are affecting their lives, change will start to happen.

Losses from the floods permeate almost every aspect of life in Grand Forks, with many suffering mental health problems, said Houghton, recalling walking into her house in hip waders and watching her possessions floating into the front yard.

However, the community spirit and the work of volunteers has been extraordinary, she said.

“It has really brought the town together. There have been a lot of low lows, but a lot of high highs,” she said.

A poster in a downtown Grand Forks coffee shop offers a help line for residents feeling frustrated and overwhelmed with life after the floods. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Graham Watt agrees that the community spirit has been remarkable, but the darker elements include eye-opening difficulties and delays in dealing with insurance companies and assistance programs that favour those who had more expensive properties, while those who were getting by with cheaper housing are now being pushed into poverty.

A report on the Grand Forks Economic Disaster Recovery Program by the B.C. Economic Development Association concludes that changes to infrastructure must be made at the local level, with help from the federal and provincial governments, and that support programs be revamped.

“The Province of B.C. must consider a complete review of support programs like DFA, Agri-Recovery and more,” the report says.

Flooding in Grand Forks in the spring of 2018 surrounds the log yard of Interfor. Photo: Sergeant Mike Wicentowich

Tina Rae is one of those who will receive a buyout for her house, but after living in a trailer in a friend’s backyard with her partner, cat and dog, she has temporarily moved in with relatives as she cannot find anywhere to rent with her animals.

The buyout cannot replace her home of 18 years or erase the trauma of having to move out as the water rose, she said.

Flags showing community support line a fence in South Ruckle, one of the Grand Forks neighbourhoods most affected by the 2018 flood. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

An RV, skirted with insulation, will have to suffice for one resident of South Ruckle as a housing shortage forces people with damaged homes to make tough decisions with winter on the horizon. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Wood smoke rises from an RV’s chimney in downtown Grand Forks. Many residents have been forced to find temporary living solutions due to homes being damaged beyond repair by the spring floods. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

An insulated RV will have to suffice for the winter for many residents who are still unable to return to their flood-damaged homes. Some people are choosing to live in local motels until insurance money or buyouts go through. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

“My daughter came down and the next day they went down to get my cat out of the house. They had to kayak into five feet of water. The cat was on the couch, which was floating in the living room,” Rae said.

Making matters worse, insurance claims were denied because their home was in a flood plain, although they still have to pay premiums and the mortgage.

Many people are struggling, Watt said.

“On the wellness side we are hearing there’s an increase in opioid use and substance misuse. There’s an increase in mental health concern, as is typical when a major disaster hits the community,” he said.

Courtnay Redding in the small shed she and her husband Jesse are converting into a living space for the winter. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Frosty sandbags on the Reddings’ property, remnants of the floods that flowed over them this spring. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

The Kettle River at sunset, downstream of where it joins the Granby River. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Long before the floods, studies by independent foresters pointed to problems with unsustainable logging in the Kootenay Boundary Region, compounded by excessive road building and overestimation of the amount of timber in the Timber Supply Area within that region.

“Yes, Grand Forks had a lot of rain in the spring of 2018, but, if the upstream watersheds had not been unsustainably logged, especially at the high elevations, because of the timber supply for the annual allowable cut having been overestimated by 20 per cent, the flooding might not have been nearly as severe,” said Anthony Britneff, a retired registered professional forester who spent 40 years working for the B.C. Forest Service.

Location of the Kootenay Boundary Region’s Timber Supply Area. Graphic: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

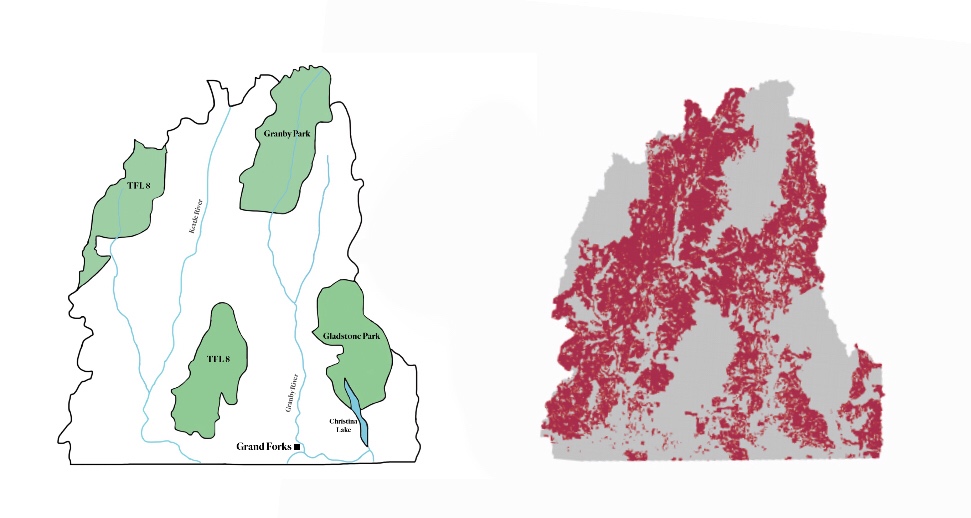

Left: The Kootenay Boundary Region Timber Supply Area, showing the two locations of TFL 8 or Tree Farm Licence 8. A Tree Farm Licence is an area-based tenure that grants exclusive rights to harvest timber. Right: the “timber harvesting land base” as identified by the province of B.C. Graphic: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Clearcuts and roads remove the natural forest cover, allowing deep snow to accumulate and then melt much faster than in a forest setting.

Compounding the problem, most of the logging has occurred at high elevations, where the majority of the watershed is, meaning higher than normal spring runoff can be anticipated, Britneff said.

Martin Watts, a professional forester and forestry consultant, has done studies showing that computer models are flawed and the amount of timber in the Boundary Timber Supply Area has been overestimated by 20 per cent.

Watts said the ministry has never been able to disprove his conclusions, but he has not been able to convince the Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations that there should be an immediate reassessment of the timber supply and the amount of trees the province allows to be cut in any given year, known as the “Annual Allowable Cut.”

“To this day, the previous and present government has provided no evidence to support its claim that the timber volume is not over-estimated by 20 per cent…When one combines a rate of logging that is 20 per cent above a sustainable level with excessive logging at high elevations, the result is flooding,” Watts said.

Fred Marshall, a retired forester, in his home near Greenwood, B.C. Marshall believes one of the main causes of the 2017 and 2018 floods was excessive clearcutting in the many watersheds that feed into the Granby and Kettle river systems. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Solitary larches, left as seed trees, stand in cutblock 04Q-09. A 2016 report by the the Forest Practices Board investigated a complaint made by a local hunter regarding the 454-hectare clearcut. Under normal circumstances cutblocks are required to be no more than 40 hectares but loopholes and exceptions allow companies like Interfor to regularly expand that size. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

In an October letter to Britneff, Forests Minister Doug Donaldson said he is satisfied harvesting decisions “are based on sound environmental and biological principles” and he has confidence in the chief forester’s decisions.

“Those determinations are based on a large body of research, inventory data, field work and monitoring, all with an appropriate consideration for the uncertainty that is inherent to this type of growth and yield analysis and modeling,” Donaldson wrote.

Giving weight to claims of excessive harvesting and road building in the watershed, the Forest Practices Board upheld a 2015 complaint by the Friends and Residents of the North Fork that the density of logging roads meant the threatened Kettle-Granby grizzly bear population was not being adequately protected.

The Board found the government had not taken adequate action to address road density and that the licensees — B.C. Timber Sales and Interfor — did not follow road density targets because they were not legally required to do so.

Roy Schiesser, spokesman for the Friends and Residents of the North Fork, has lived in the area for 20 years and noticed about six years ago that the logging rate was accelerating, together with road construction.

“People now realize that the underlying problem is that we have overcut and overcut the high elevations. I don’t think the residents were aware of how much was going on, but I think people are now are ready and willing to look at options,” said Schiesser.

“It’s not going to get better. It can only get worse if we think we can keep on building roads and overcutting and deal with the aftermath afterwards,” he said.

Despite the Forest Practices Board decision, little has changed and, in addition to more road building and lack of oversight of road deactivation, B.C. Timber Sales is allowing massive clearcuts, said Fred Marshall, a professional forester who owns Marshall Forestry Services and operates a woodlot close to Grand Forks.

“We have been opening up way more forest than we have historically. Big clearcuts. Interfor just cleared about 450 hectares and the other day when I was out there’s another one in the [B.C. Timber Sales] area that I think is close to another 400 hectares. It’s a huge area — inordinately so,” Marshall said.

The log yard and mill of forestry giant Interfor is located in the heart of Grand Forks. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Fred Marshall walks through a 454 hectare cutblock in the mountains between Greenwood and Grand Forks. Marshall, a retired forester, believes that massive cutblocks like this contribute to spring flooding because of rapid snow melt and non-existent topsoil. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

B.C. Timber Sales, which auctions off Crown timber sales licences to the highest bidder, is responsible for 40 per cent of the Annual Allowable Cut in the Boundary region and is also responsible for building and maintaining logging roads, but Marshall said with exasperation that when he asked the crown corporation about the number of roads, he was told they did not know.

“We now have over 16,000 kilometres of roads in the Boundary…The roads are everywhere and the clearcuts are massive. There is no more natural and, hence, the forest doesn’t have the capacity to absorb any large, natural events like it did in the past. It doesn’t have the resilience,” Marshall said.

“There is no question that (the floods) will happen again. More roads are being built and more logging is being done as we speak,” said Marshall.

About 30 years ago the annual allowable cut was 700,000 cubic metres, but, after two large protected areas were formed — Gladstone Provincial Park covering 40,845 hectares and Granby Provincial Park which covers 39,300 hectares — the chief forester kept the cut at the same level.

“How did that happen?” Marshall asked. “It was magic. We lose a huge part of the land base and the cut stays the same.”

Logging is taking place on steeper slopes, the mountain pine beetle has taken its toll and yet there is pressure to log more, he said.

“We are pushing the envelope in every direction.”

Interfor mill and log yard. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Smoke from slash pile burning fills the Kootenay Boundary valleys southwest of Grand Forks. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

But the forests ministry says there are no problems with the cut rate in the region and harvest levels are regularly monitored to ensure licensees are meeting their commitments.

Clearcutting in any watershed in the region must not exceed 20 per cent and no operations have exceeded that number, said a ministry spokesperson.

The annual allowable cut is reviewed every decade by the chief forester and, although the annual allowable cut for the Boundary region was last set at 700,000 cubic metres in May 2014, it was adjusted to 670,142 cubic metres in October 2016 because of the creation of a new community forest, she said.

“The inventory for the Boundary Timber Supply Area is currently being updated and monitoring plots are being established to support future decisions,” she said.

Any future assessments will include the cumulative effect of road densities, she said.

As questions about forestry practices in the Boundary Region became louder, renowned forest ecologist and ecosystem-based forester Herb Hammond took a look at the area on Google Earth.

“I was shocked by what I saw. Talk about ill-designed forestry, it’s a perfect example of it,” he said.

The simple reality is that clearcuts intercept 30 to 40 per cent more snow, meaning snowpacks are deeper than in the adjacent forests, and then the snow melts faster in the spring because it is not shaded by surrounding forests, Hammond said.

“You cross the threshold where you have done way too much and the system just falls apart and that’s what happened,” he said.

“It’s not something that’s going to go away, particularly in this era of deeper snowpacks in this phase of climate change and it’s not something you can easily fix…The damage will continue to grow as long as this kind of ill-conceived forestry continues,” he said.

Roads divert natural water courses disrupting the hydrological cycle and leading to higher peak flows — meaning floods — and lower low flows — meaning droughts, Hammond said.

“When you look at the Kettle Valley you have clearcuts right down from the top of the watershed to the bottom of the watershed and so you desynchronize the water flow,” he said describing B.C.’s forestry practices as a sordid mess, with government hand in glove with the industry and a total lack of accountability.

“The Kettle Valley is a tragedy and what happened in Grand Forks is a tragedy but it’s happening in a lot of places,” Hammond said.

The picture of a community struggling to recover from a flood that many believe could have been much less severe if forestry practices had been different infuriates Britneff.

“The residents of Grand Forks need to hold the forests ministry to account for what some would describe as a crime against wildlife and humanity, a crime still being played out at high elevations in the sub-watersheds around Grand Forks,” Britneff said.