A Toronto-area regional council will vote this year on the fate of 5,000 acres of farmland, deciding the balance between growth and environmental protection in the area for decades.

Halton Regional Council — which includes the mayors and representatives of Burlington, Oakville, Milton and Halton Hills, west of Toronto — must decide whether to add parcels of farmland scattered to the southeast of Halton Hills and Milton to its urban boundaries, therefore opening them up for development. If council votes no, it would be a rejection of sprawl, made in defiance of the provincial government, which is making big promises about increasing housing stock in advance of this spring’s election. If council votes yes, it will be a blow to environmentalists, who want to preserve local farmland and resist unfettered development in Toronto’s outer suburbs.

Those against opening more land to development argue that farmland can be a crucial carbon sink and source of local food, while car-reliant suburbs produce air pollution and carbon emissions. Those in favour say they also want to protect the environment and avoid sprawl, but feel it’s impossible to build enough homes to accommodate Halton’s rapidly growing population without stretching outward.

Halton’s big question comes amid a broader societal shift, said Matti Siemiatycki, a professor of geography and planning at the University of Toronto and the director of the school’s Infrastructure Institute. He said that most decision-makers seem to understand sprawl can’t go on forever, and that new development must be dense and integrated with public transit. But even as politicians and municipal planners acknowledge that emissions and commute times must both come down, he said, many are still seeking lower-density development on the fringes of the region.

“The plans are there to achieve a region that is trending towards greater sustainability,” Siemiatycki said, pointing to the province’s growth roadmap, which emphasizes the need to protect the environment, preserve farmland and increase transit access.

“It’s the distance between what’s on paper, and the rhetoric and the practice and what actually gets built that I think is challenging.”

Versions of Halton’s soul-searching are playing out in municipalities across southern Ontario. As part of a rewrite of the region’s growth plan in June 2020, the province ordered cities in the Greater Golden Horseshoe — an area encompassing the Greater Toronto Area, Hamilton and Niagara — to decide how they want to structure the next three decades of growth by this coming July.

Environmentalists say the Ford government’s rewrite of the growth plan has effectively stacked the deck to ensure more sprawl, allowing less density, basing its targets on over-inflated population projections and asking municipalities to plan an extra decade ahead of what is customary. Critics argue such moves largely benefit investors who buy and sell the valuable land on the fringes of cities, while harming local government coffers in the long run: neighbourhoods populated with single family homes instead of more dense development result in fewer taxpayers.

“We are nowhere near ready to make a decision of this magnitude,” said Burlington Mayor Marianne Meed Ward, who is pushing against the boundary expansion. She wants regional planners to look at alternative options and to wait for an assessment of Halton’s agricultural land to be completed before deciding to open more for development.

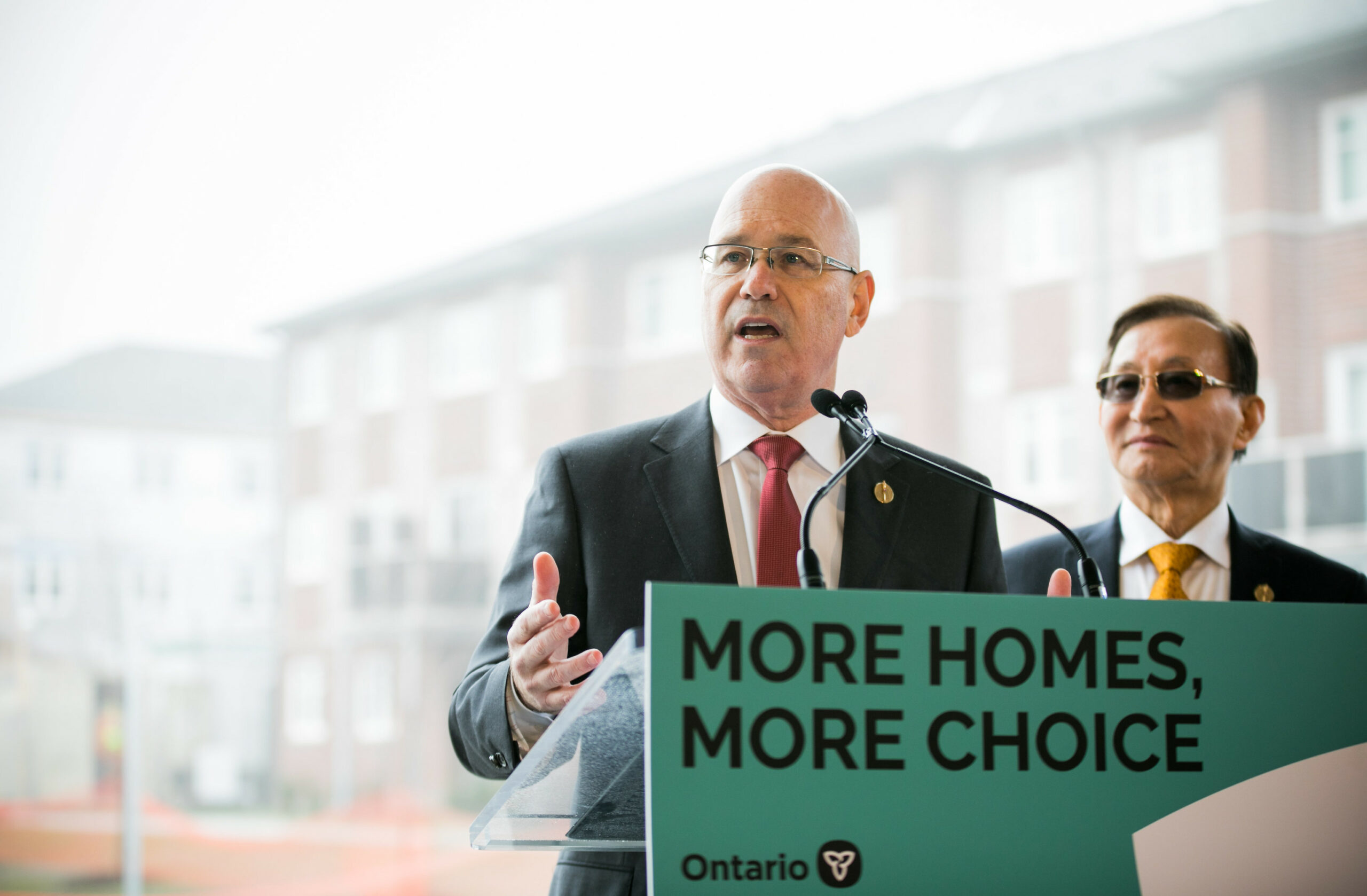

Meed Ward also wants to follow the precedent set by other councils. She points to the neighbouring city of Hamilton, Ont., just south of Halton, where council voted last year to keep growth within its existing urban boundaries despite warnings from the province that it would risk not having enough new homes for its rising population. Though Ontario Municipal Affairs Minister Steve Clark has signalled he might override the decision, he hasn’t done so. Ward thinks this leaves an opening for Halton Regional Council to disregard the province’s wishes and go back to the drawing board.

“There is no planning jail … the minister wasn’t terribly happy, but (Hamilton Mayor) Fred Eisenberger still walks the streets,” Ward said.

‘Once the land is gone, the land is gone’

The proposal to expand Halton’s urban boundaries is meant to accommodate rapid growth in the region — known for its panoramic views of the Niagara Escarpment, rolling farm fields and suburban neighbourhoods. The Ontario government has mandated the region to prepare for 1.1 million inhabitants by 2051, roughly double the 580,000 who live there now.

Figuring how best to accommodate that change is challenging in a place like Halton, which has multiple layers of government with different goals tackling the same issue, Siemiatycki said. The province holds much of the power, but municipalities are tasked with writing their own policies, and four different municipal councils must work together as Halton Region. Meanwhile, the federal government controls immigration, which in the Greater Toronto Area is significant fuel for growth.

“There’s just a lot of cooks in the kitchen,” Siemiatycki said. “It’s really hard to co-ordinate.”

Most councillors from Milton and Halton Hills are in favour of the urban boundary expansion, while those from Oakville and Burlington have come out against it.

Meed Ward says it’s foolish to try to plan 30 years ahead when the region is changing so quickly. “My kids will do jobs that aren’t even invented yet,” she said. “We really should be extremely cautious about making any irreversible decision on farmland which feeds us … it’s bound to be wrong.” In 2019, she and the rest of the regional council declared a climate emergency, pledging to urgently respond to the crisis.

Halton has already set aside thousands of acres for development through 2041 that haven’t been touched yet. The region is also planning to build higher-density housing — like townhomes, multiplexes and apartments — within its existing urban boundaries. In an emailed statement, Halton Region planning staff said more than 85 per cent of new housing units would be built on land that’s already been set aside. But the planners say they’d need the other 5,238 acres of what’s currently farmland in Milton and Halton Hills to meet the provincial government’s expanded growth targets. Though broken up into a handful of parcels extending from the region’s boundaries, the addition would add up to about an area just smaller than Georgetown, the largest community in Halton Hills.

The region’s plans include a larger proportion of high-density development than what it has right now, but they also include “reasonable amounts” of lower-density that takes up more space, like detached houses and row houses, planning staff said in an emailed statement. Though it looked at options that involved making the existing urban area even denser, doing so would “result in a very high proportion of apartment units well beyond market demand in Halton,” putting the region out of step with the provincial government’s guidelines, planning staff said.

In Milton, Councillor Zeeshan Hamid said the region is already trying to add more compact development like condos, and that making the existing urban area as dense as possible still wouldn’t be enough to fit all of the planned growth. Many people also still want low-density single family homes, Hamid said, and he believes that if they don’t find it in Halton they’ll go further afield, which could worsen sprawl over time.

“I think everyone around the council, and the vast majority of our citizens, we all agree that we really need to control sprawl,” he said. “If we start to assume Milton and Halton Hills … is an island of its own where we can somehow impact the wider housing demand or the wider population growth and immigration policy or climate change, that’s where the misconception comes in.”

Hamid believes it’s hypocritical for people who live in single-family homes to argue that newcomers can’t have the same lifestyle they’ve chosen for themselves. And although preserving farmland is important, so is housing affordability.

“We need to understand the entire breadth of the problem we’re trying to solve,” Hamid said. “Because if we over-index on just one area, we’ll end up making the problem worse.”

Phil Pothen, the Ontario program manager for the non-profit Environmental Defence, said low-density neighbourhoods aren’t everyone’s top choice. Some of the region’s most desirable places to live are populated, transit-accessible and walkable areas like downtown Toronto’s Little Portugal, he said, which has a mix of condos and smaller single-family homes with yards.

“We’re trying to make that option available to people who can’t afford the (downtown) core, and replicate that same lifestyle within the suburbs,” he said.

Late last year, a groundswell of local activists formed the group Stop Sprawl Halton, which argues the region could avoid building on farmland if it made its existing urban areas denser. The group doesn’t want neighbourhoods of just enormous condo towers, said founding member Kim Bradshaw, who lives in Milton. They want to see more medium density too, like low-rise apartment buildings and laneway housing, in tandem with measures to make the region more accessible by walking and transit.

“I think it would be a huge improvement to our community to get some density and walkability,” Bradshaw said. “But if they get that 5,000 acres, I don’t see it. I see just more sprawl.”

Expanding the urban boundary would eat up crucial farmland, some of the best in the country. In 2016, Halton Region found agriculture in the area has declined as its towns have grown outward, part of a larger trend in Southern Ontario.

Even among farmers, there’s disagreement about what to do, said Allan Ehrlick, the president of the Halton Region Federation of Agriculture, which represents over 350 farmers in the area. Some farmers, whose children aren’t interested in taking over, are seeking to sell their land and would welcome the property value increases that come with the option to develop. Others worry about local supply chains for food and crops. The local agriculture and food industry is responsible for about a quarter of the jobs in Halton Region — farms in the area that could be developed mainly produce corn and soybeans, a regional assessment found.

“Those who are in the process of selling farmland are going to make out very well because prices are really high,” Ehrlick said. “On our board, we just feel that (the urban boundary expansion is) gonna cause irreversible damage to Halton’s agriculture industry. I mean, you can’t grow food on asphalt, and once the land is gone, the land is gone.”

Halton Region ‘in no position to make a decision,’ Burlington mayor says

Halton’s next steps aren’t clear yet. Regional council had originally planned to vote on the boundary expansion on Feb. 9, but amid backlash from local advocates, it postponed the decision. Instead, planning staff will hold a workshop with councillors to answer questions about the path forward. No date for another vote has been set, though regional planning staff said in an email that it will have more information in the coming weeks.

Pothen said municipalities must have the guts to re-open existing local plans, tweak their zoning rules and add more density.

“It’s hard on the ego,” he said. “What it involves is the current Halton Regional Council and, frankly, the current planning staff, admitting that they’ve got it wrong until now.”

Meed Ward said a pause on the discussion is needed until at least 2023, when Halton’s agricultural assessment is scheduled to be done. She wants the region to make any necessary policy changes and create an overall plan for supporting agriculture before deciding to give up over 5,000 acres.

“There were enough of us that felt, you know, we’re in no position to make a decision,” she said. “And if you force it, it’ll probably fail. And then what?”