Water is precious — and precarious — on First Nations reserves like this one

Boil-water advisories in Moose Factory, Ont., are frequent, expensive and ongoing — but not ‘long-term’...

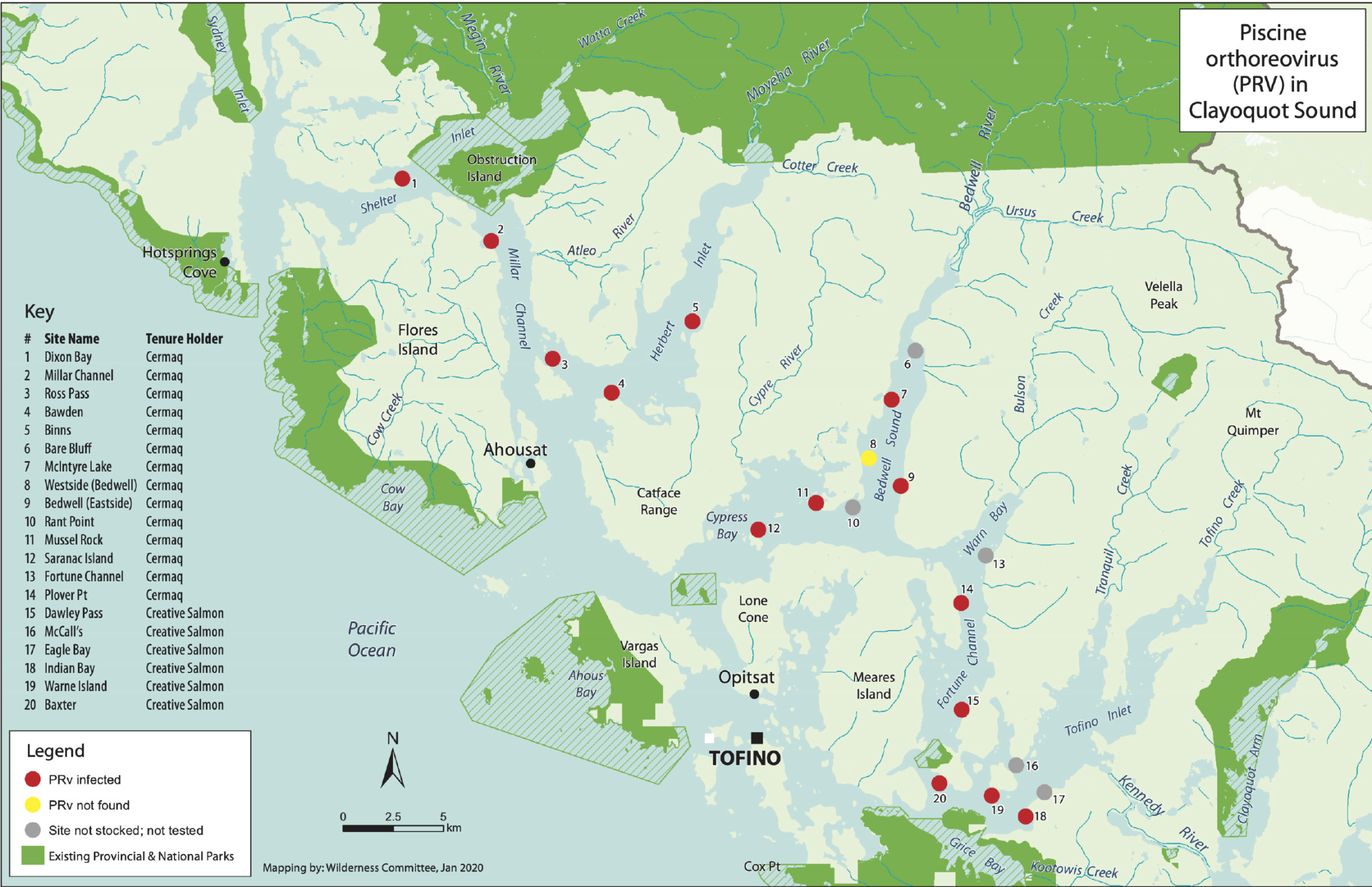

Salmon at a majority of Clayoquot Sound fish farms are infected with the Norwegian strain of a highly contagious virus, according to an investigative report released Wednesday.

The report by Clayoquot Action, a Tofino-based conservation society, says feces, flesh and scale samples from 14 out of 15 farms tested positive for the piscine orthoreovirus, a disease that gained notoriety after a video of bloody discharge from packing plants in Tofino and Campbell River went viral in December 2017.

Laboratory testing by the B.C. government showed the underwater effluent was contaminated with piscine orthoreovirus, a disease found in 80 per cent of farmed Atlantic salmon that is linked to a host of fish health problems, including heart and skeletal muscle inflammation and haemorrhages in internal organs.

Clayoquot Action campaigns director Bonny Glambeck said it’s particularly concerning to find piscine orthoreovirus on Chinook salmon farms located along wild salmon migratory routes in the Clayoquot Sound UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, off the west coast of Vancouver Island.

Four of the active farms the group tested are owned by Creative Salmon, the only company raising Chinook on a large scale in open net pen farms in B.C. Most B.C. open net pen operations — including 11 other active farms tested for the study, which are owned by Cermaq, a Mitsubishi subsidiary headquartered in Norway — produce Atlantic salmon, a species not native to the Pacific Coast.

“Wild Chinook salmon in Clayoquot Sound are on the brink of extinction,” Glambeck told The Narwhal.

“This is just the final nail in the coffin with all the stresses that the wild salmon are undergoing right now.”

An open-net pen salmon farm in Clayoquot Sound. Photo: Clayoquot Action

Fisheries and Oceans Canada says a B.C. strain of piscine orthoreovirus has been found in salmonids off the B.C. coast since 1987 or 1977 — about the time salmon farming began — and has a “low ability” to cause disease.

Laboratory testing commissioned by Clayoquot Action found the strain in Clayoquot Sound fish farms is a Norwegian variant of the disease, known as PRV-1a.

Atlantic salmon eggs — 30 million of which were imported to B.C. — are the most likely source of contamination, according to the report, Going Viral: Norwegian Salmon Farm Virus Threatens Clayoquot Chinook.

“It’s very, very concerning,” Glambeck said.

“They are essentially denying the existence of this Norwegian variant in British Columbia waters … It’s just shocking to me that they continue to deny that it is damaging and dangerous to wild salmon, pretending that it’s not happening.”

Terry Dorward, a Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation councillor, said the federal government is spreading “disinformation” about the piscine orthoreovirus variant found on salmon farms in Clayoquot Sound, whose biodiverse rainforest islands support many species dependent on wild salmon.

“This is similar to what my people — Indigenous people — experienced when we were given smallpox blankets,” Dorward told The Narwhal. “We were nearly wiped out. And I believe the same thing is happening to our wild salmon.”

There is scientific evidence that piscine orthoreovirus is harmful to salmon. A June 2018 DFO study confirmed that piscine orthoreovirus in Pacific Chinook is strongly associated with the rupture of red blood cells, resulting in jaundice, organ failure and death.

The findings suggest that “migratory Chinook salmon may be at more than a minimal risk of disease from exposure to the high levels of PRV occurring on salmon farms,” according to the study.

Shawn Hall, a spokesperson for the B.C. Salmon Farmers Association, said there is “nothing new” about information in the Clayoquot Action report.

Hall said the same variant of the virus is present in both B.C. and Norway and “is not virulent. It doesn’t make fish sick.”

“Our fish go into the ocean without PRV, from land-based hatcheries which are based here in B.C.,” Hall said.

“We’re not importing anything. Our fish are raised from local broodstock in local hatcheries. They go into the water without PRV and they pick it up in the ocean just as wild fish do … the strain that they found is the strain that we knew was here and it’s not causing significant issues.”

Hall pointed to a study conducted in 2018 after fears were raised, following the video of bloody discharge at the packing plants, that wild salmon could be harmed by piscine orthoreovirus.

The study notes that piscine orthoreovirus is a causative factor to the disease Heart and Skeletal Muscle Inflammation (HSMI), that fish infected with the virus may not exhibit any symptoms and that the virus appears to have far less of an impact on fish in B.C. than it does on salmon in Norway.

The study, conducted by researchers at the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences and UBC, also notes research gaps that need to be addressed “as PRV is a recently discovered virus and its pathogenicity to salmonids is still a mystery.”

Wild salmon smolts swim past the open nets of a fish farm in Clayoquot Sound. Photo: Tavish Campbell

Dorward said an agreement the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation signed with Creative Salmon has been “in limbo” since the chief and council voted last year to ask the company to remove open net pen farms from the nation’s traditional territory.

The vote followed a visit to salmon farms last summer, when Dorward said he and others saw deformed farmed fish and wild salmon swimming through open net pens.

“Over the years we’ve witnessed the collapse of the fisheries and the negative impacts it has to our coastal communities … We know there’s other factors involved, [like] climate change … Some things we can’t stop. But we can stop this particular issue of open net salmon farms,” he said.

“These organisms are extremely successful viruses that can mutate and spread. The protection of our wild salmon is at great risk here.”

In 2018, the state of Washington announced that open net pen Atlantic salmon fish farms would be phased out by 2025. The state also stopped hundreds of thousands of salmon infected with an Icelandic strain of piscine orthoreovirus from being transferred to the farms, saying wild salmon could be at risk.

A map showing the location of fish farms in Clayoquot Sound. Sites where the piscine orthoreovirus was found are denoted in red. Map: Wilderness Committee

Clayoquot Action is one of a number of groups and First Nations calling on the federal government to prohibit the transfer of piscine orthoreovirus-infected fish to open net pen farms.

Last year, following parallel legal cases brought forward by biologist Alexandra Morton and the ‘Namgis First Nation that aimed to prevent the transfer of smolts infected with the virus to open net pens, the courts ordered Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) to revise its piscine orthoreovirus policy and apply the precautionary principle by June 4. DFO subsequently received a four month extension from the courts.

But during the fall federal election campaign, when there was no sitting fisheries minister, DFO said it would not screen for piscine orthoreovirus or prevent the transfer of piscine orthoreovirus-infected fish to salmon farms.

In an emailed statement in response to questions from The Narwhal, DFO said it had determined in October 2019 that testing for the B.C. strain of PRV is not required under fishery regulations in order to authorize a fish transfer license.

“While this decision was based on best available information and science, the department will continue to adapt its approach to managing PRV, if warranted by new science or information,” the statement said.

DFO also noted the World Organization for Animal Health does not consider PRV to be a reportable disease and there is no human health risk associated with the virus.

The ‘Namgis First Nation is now taking the federal government back to court, asking for a review of the October 2019 decision to continue to allow salmon farms to be stocked with piscine orthoreovirus-infected fish.

As a campaign promise, the Trudeau government pledged to work with the province of B.C. and Indigenous communities to create a plan to transition from open net pen salmon farming in coastal B.C. by 2025 — a commitment also outlined in the mandate letter for Bernadette Jordan, the newly appointed federal Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard.

Many people interpreted the promise to mean open net pen farming on B.C.’s coast would end by 2025. Yet Jordan subsequently clarified that she has five years to prepare for a transition, implying that open net pens could remain in coastal waters past 2025.

Dorward said the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation wants Creative Salmon either to move to closed containment systems for salmon farming or to transition to kelp farming, which he said would also create jobs, be better for the environment and help meet a growing global demand for kelp.

“We need to be more proactive and creative in finding solutions to these disease outbreaks or we’re going to completely wipe out our wild salmon which we greatly depend on on the west coast,” he said.

Glambeck said a team of staff and volunteers conducted 25 field trips to the fish farms, scattered along Clayoquot Sound’s meandering inlets, from May to December 2019. Farms were visited multiple times, she said.

Sampling vials used by researchers with Clayoquot Action. Photo: Jeremy Mathieu

“We would use a fine mesh aquarium net on a long pole and we would go around the fish farms — very close, within a few feet of the farms — and we would just scoop up little bits of fish scales and feces and bits of flesh, the type of thing that floats out of the farms.”

Dozens of samples were put on ice and shipped by courier to the Atlantic Veterinary College where they were tested by virology professor Fred Kibenge, chair of the department of pathology and microbiology. Kibenge, who declined to be interviewed, is editor of the journal Aquaculture.

Some of the samples were taken last November after an unseasonable algae bloom caused a massive die-off at Cermaq operations in northern Clayoquot Sound, killing 200,000 fish. Clayoquot Action sent decomposing flesh and other matter from the die-off to the Atlantic Veterinary College, where it tested positive for the Norwegian variant of PRV.

Glambeck said she first heard of piscine orthoreovirus during the Cohen commission investigation into the decline of Fraser River sockeye, when federal government genomic scientist Kristi Miller testified that she had been asked to help Creative Salmon diagnose why fish were jaundiced and discovered the company’s farmed Chinook had piscine orthoreovirus (PRV).

“It’s a particular concern that Creative Salmon has PRV on their farms that is replicating and adapting to a specific species, and spreading through the waters of Clayoquot Sound,” Glambeck said.

“Viruses and pathogens on these farms become more virulent with the amount of fish crowding on the farms so we’re really concerned that this virus will become even more dangerous to Chinook and other Pacific species than it is now.”

According to the report, a salmon farm infected by piscine orthoreovirus can release as many as 65 billion viral particles an hour, which are spread far and wide by tidal currents.

“Because fish breathe by passing water over their gills, it is dead easy for PRV to enter the bloodstream of wild fish,” the report said.

Salmon farming companies referred questions to the B.C. Salmon Farmers Association.

Updated at 2:40 p.m. on Feb. 6 to include comment from DFO, which was not able to respond to questions by our deadline.

Updated at 12:40 p.m. on Feb. 7 to add the words “Atlantic salmon” to the following sentence: In 2018, the state of Washington announced that open net pen Atlantic salmon fish farms would be phased out by 2025.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. When I visited my reserve, Moose Factory,...

Continue reading

Boil-water advisories in Moose Factory, Ont., are frequent, expensive and ongoing — but not ‘long-term’...

On the election trail, Canada's federal leaders are pushing military and industry in the North....

President Trump’s threats towards Canada carry great risks to Americans as well, and to the...