Hope for a huge, ancient and imperilled fish

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

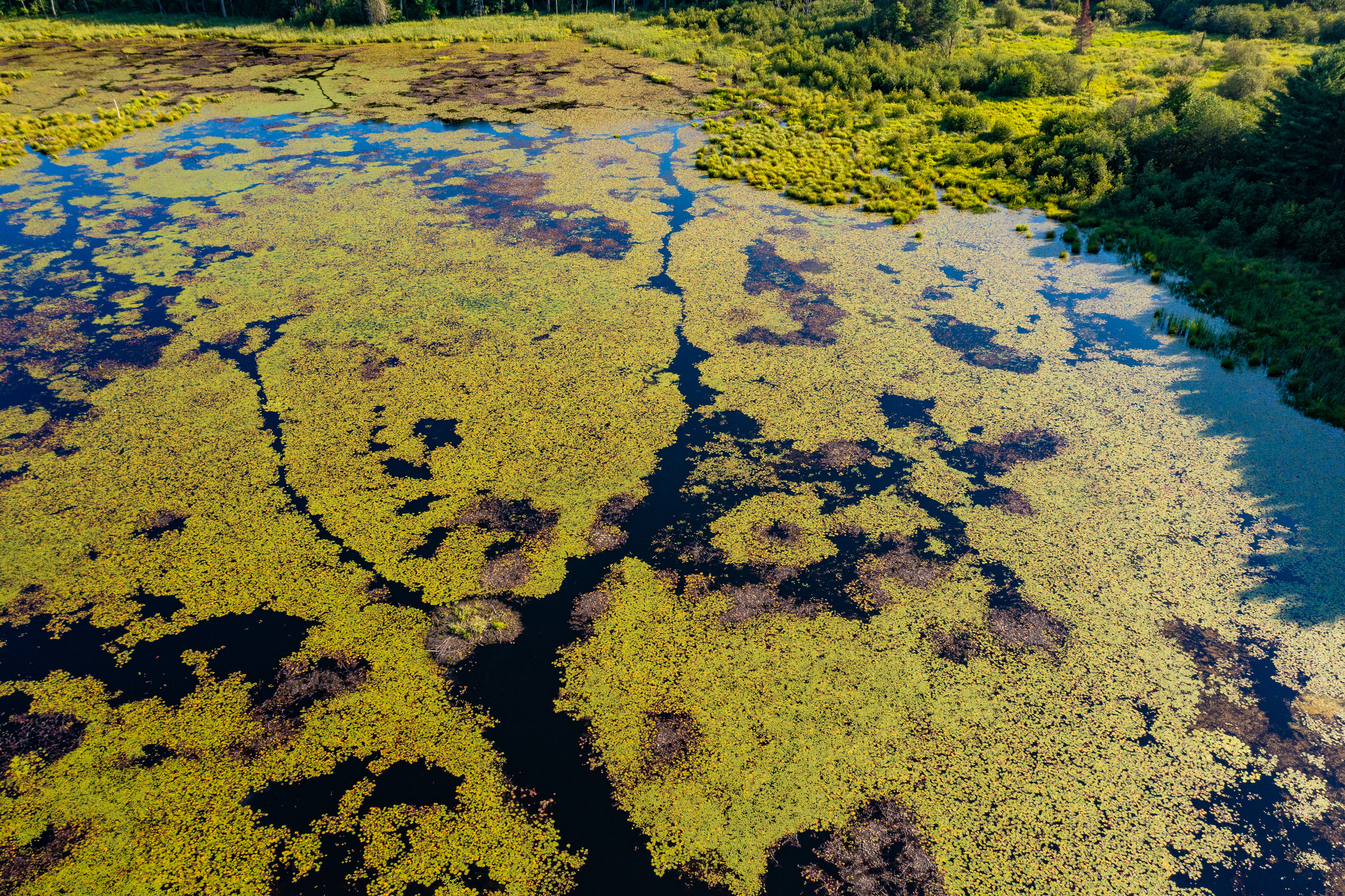

From the marshes and swamps that dot the land surrounding the Great Lakes to the bogs and fens scattered farther north, Ontario is a province of many, many wetlands.

If you’ve spent time in the rocky stretches of the Canadian Shield — where water often pools in stony hollows and wetlands can seem a dime a dozen — it can be hard to believe that the soggy landscapes left are just a fraction of what was here 150 years ago, before European settlers began filling them in. In southern Ontario in particular, about three-quarters of the wetlands that once existed are gone.

Of the ones that remain, a vanishing few are protected from development. An even smaller number have been assessed to see if they’re worth preserving: just 30 in the past decade. Fewer still are bestowed with protective status at the end of the expensive, time-consuming assessment process, a title known as “provincially significant.” Only one site achieved the title from May 2021 to May 2022 — which is why it’s so remarkable that a group of citizens managed to secure it this year for a soggy site in Bracebridge, Ont., a stone’s throw from Lake Muskoka.

Though the newly minted South Bracebridge Provincially Significant Wetland Complex shows the height of what a group of people who care can accomplish, the lengths they had to go to also show why the existing wetland protection system can seem impossible to navigate. The process required thousands of hours of volunteer work, a small army of hired experts and ultimately, half a million dollars.

“How does the average person cough up the dough to fight something like this?” Michael Appleby, a director of the non-profit South Bracebridge Environmental Protection Group, said.

“They don’t. The whole thing is stacked against them.”

It’s a process that matters more than ever. Wetlands are a natural climate solution — they absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. They provide a home for species at risk and soak up rain and melting snow that could otherwise cause floods. Even small or degraded ones have an outsized impact on their ecosystems.

They’re also disappearing. Last year, Ontario’s auditor general concluded the province’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry — which has made it harder to protect wetlands and abandoned a strategy aimed at conserving them — has done very little to prevent more from being filled in or paved over.

Another member of the south Bracebridge group, Lisa Cumber, said advocates don’t exactly see an ally in the politician charged with overseeing Ontario’s wetland policy, Natural Resources Minister Graydon Smith. Before entering provincial politics, Smith was the mayor of Bracebridge, and voted in favour of allowing development near the wetland in 2021 without doing an assessment first. After the group appealed Bracebridge’s decision to a provincial tribunal, the project is going ahead but with stronger environmental protections.

Smith’s office didn’t respond to questions from The Narwhal, including whether any other wetlands have been designated as provincially significant this year. Back in 2021, however, Smith said he didn’t take the decision to approve the development lightly.

“It’s probably easy for people to say I’m being insincere when I say we’ve listened to the community and appreciated those comments but voted in a way that some people in the community don’t support, but such is the life of folks on council,” he told local media.

So, what’s a would-be wetland protector to do?

“The system is broken,” Cumber said. “The public has to keep pushing and pushing.”

Before they were a development battleground, the south Bracebridge provincially significant wetlands were best known as a hiking spot for cottagers and locals alike, brimming with life. In most seasons, birdsong echoes through the air — over the years, people have reported seeing 177 different avian species there — while frogs and turtles poke their heads out of the water.

The Trans Canada Trail wraps around the public stretch of the wetland, known as Henry Marsh, which connects to other wetlands on the property that’s now set to be developed. It drains into the Muskoka River, which empties into Lake Muskoka, an iconic cottaging hotspot.

The Town of Bracebridge, however, had decades ago earmarked the area around the wetland complex as part of its urban centre, meaning the properties around the trail could eventually be rezoned for development. A highway is set to be built there too, one day. Various people proposed various projects over the years, but nothing stuck — until 2018, when Toronto entrepreneur George Chen applied to the town to build a private boarding school there.

Plans for the school, which will be called Muskoka Royale College, show a campus of about 180 hectares. It includes five “precincts” — classrooms, residences and a fitness complex, connected by roads winding through open space. When finished, it will be home to 1,800 students.

Quinto Annibale, a lawyer representing Muskoka Royale who is also known for his work with the right-wing group Vaughan Working Families, told The Narwhal the developer planned the project as if the wetlands were provincially significant even before the official designation.

“Protection of the environment and the wetlands and all other natural heritage features on the property has been, and will continue to be, a paramount concern for my client,” Annibale wrote in an email.

Provincial urban planning rules can restrict development in and around significant wetlands, but they don’t require a wetland evaluation before building starts. And as a private project, Muskoka Royale isn’t subject to a provincial environmental assessment.

Chen has submitted some environmental studies to the town. According to Annibale, Muskoka Royale’s plans would increase the amount of protected land on the property. The site was previously zoned to allow a golf course, which would have disturbed more land than the school proposal, Annibale told The Narwhal.

Still, the impact of Muskoka Royale on the South Bracebridge wetlands remains debated. Some mapping commissioned by the environmental group this fall indicates buildings could come close to the wetlands, infringing on the required buffer of space around them, and planned roads could cross them.

Annibale called the group’s mapping “inaccurate” and said the building locations on the plans were “conceptual only,” and don’t show the “intended actual location of the buildings.”

“The purpose of the plans was to demonstrate that the buildings could be accommodated within each precinct boundary while still protecting the wetlands as though they were [provincially significant wetlands],” Annibale said in an email.

As the development moved through the approval process in 2019 and 2020, locals worried the studies Chen had submitted voluntarily didn’t properly take the sensitivity of the wetlands into account. They suspected the wetlands might qualify as provincially significant, but without a formal assessment, how could anyone be sure?

A wetland evaluation takes a while. It isn’t cheap, and depending on the details of a particular project, the results can make building more difficult. But the residents felt it was important.

“There is a mentality up here that says, ‘We’ve got so much of it, that we can afford to destroy a little bit,’ ” Appleby said. “Council elected to remain willfully ignorant.”

So a mix of cottagers and year-round residents formed the South Bracebridge Environmental Protection Group in 2019 and started pushing the town’s council to ask the province for more studies.

“It was like a frickin’ high school study group,” Appleby said. “It was all of these 50- and 60-somethings hanging out together, going back to school … learning about the process. It was brutal.” What astounded them, he added, was that there seemed to be no checks and balances — no way to ensure their elected officials took their arguments seriously.

The group spoke at council meetings and asked experts to weigh in, prompting conservation group Ontario Nature and wetland scientists to write Bracebridge council in support of a full evaluation. But it didn’t seem to make a difference: in 2021, the town approved Muskoka Royale without the assessment the group had asked for. “I believe I have the information to make a decision,” then-mayor Smith said.

The group kept pushing. At one point, they even hired a public relations firm to help bring attention to the issue. They hired environmental lawyer David Donnelly to appeal the case to the Ontario Land Tribunal. They also hired ecologist Corey Stinson to do the wetland evaluation they thought was needed.

To determine the value of the interconnected wetlands in the complex, Stinson visited the site 13 times in 2022, devoting early mornings and late evenings to cataloguing the flora and fauna and how the water flowed — both on foot and using aerial photos.

“It’s kind of a magical place to be,” Stinson said. The wetlands are unusually well connected to each other, he said, covering about 140 hectares — roughly 260 football fields — storing a ton of water and forming the right habitat for a wealth of plants and animals. He found species at risk, too, like western chorus frogs and a secretive, heron-like bird called a least bittern.

Stinson scored the wetland complex using a standard provincial manual, which awards points based on factors like the species living there, human activity in the area and how much carbon it might hold. Then, Stinson fired off the results to Smith’s Ministry of Natural Resources. The ministry used to review wetland evaluations before making them official, but after the province changed the rules last year, the process is considered complete once the results have been sent to a “local decision maker.”

As of June, the wetlands officially qualify as provincially significant. All told, the South Bracebridge Environmental Protection Group’s efforts cost half a million dollars, Appleby told The Narwhal.

Muskoka, a vast area encompassing several towns and many lakes, hosts both year-round residents and cottagers. Not everyone in the region is affluent — about a tenth of its permanent population is considered low-income, according to data from the 2021 census, and the District of Muskoka says 60 per cent earn less than $40,000 per year. But many in the area, particularly the summer residents, have deep pockets. Cottage owners on Lake Muskoka include Victoria and David Beckham, Tom Hanks and Steven Spielberg.

The board members at the South Bracebridge Environmental Protection Group aren’t celebrities, and they’re a mix of seasonal and permanent residents. Cumber and Appleby, for example, both live there year-round. Some in the group do have experience dealing with governments and big businesses, though. If getting their local wetland protected was a stretch for them — despite their ability to fundraise, hire experts and spend time volunteering — it’s hard to see how most other small communities could do the same.

“I get the sense from networking with other community groups like ours that we’re clearly not alone,” Appleby said. “We just happen to be … one of the communities that had a donor community that could write a cheque and help fight back.”

In early November 2023, the tribunal issued its decision about Muskoka Royale: the project can go ahead, but more environmental impact studies must be done first and there must be a larger buffer between the areas that will be disturbed for building and landscaping and the wetlands. Originally, the town approved Muskoka Royale’s proposal of a 15-metre buffer, but reversed their support for that during the tribunal process. The buffer is now set to be 30 metres.

It’s not everything the South Bracebridge Environmental Protection Group wanted, but it’s a step in the right direction, Cumber said.

Natural features “can’t be protected if they are not recorded anywhere,” Cumber said. “So now we have a record and that is key to me.”

Annibale said the new designation “has no impact on my client’s development plans for the site.” The tribunal hearing was about whether the land could be rezoned to accommodate the school, he said: specific site plans, including building locations, are the next step in the process.

“Muskoka Royale is extremely happy with the decision and the outcome of the hearing,” he wrote in an email. “The merits of the proposal have now been confirmed by the Ontario Land Tribunal … in what is a thoroughly considered and carefully reasoned decision.”

The Town of Bracebridge didn’t respond to questions from The Narwhal.

The auditor general’s review of the province’s wetland protection rules last year found a series of problems. Many marshes that are vital to urban flood control don’t qualify for protection. Swamps that do qualify face delays in getting the official mantle. Wetlands that have not been studied can be destroyed, even if they’re likely to meet the standard for protection. At times, Premier Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservatives have also used a special land-zoning power to override wetland protections and allow development.

A matter of weeks before those findings were released, Smith’s ministry rewrote the provincial manual used to evaluate whether a wetland is provincially significant, making it harder for sites to gain or keep protection. The Bracebridge wetland is one of the first to be evaluated under the new rules. It still made the cut, but nearly 50 hectares of vernal pools in the complex — or wetlands that contain water for only part of the year — were not protected, although they would have qualified under the old rules.

Although the province has invested in some piecemeal wetland restoration projects, Smith’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry didn’t commit to a single one of the auditor’s recommendations to make the system better. For example, the auditor suggested Ontario look to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, where wetlands that haven’t been studied receive a default protection until they can be assessed. As of now, that’s not happening here.

Cumber said she believes it’s worth fighting to fix Ontario’s flawed system for protecting wetlands, even if she doesn’t have a lot of faith in the decision-makers.

“I think the system is broken, but it’s also broken because nobody’s been held accountable,” she said. “Now, they’ve been challenged.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. Angello Johnson’s shoulders burn, and his arms...

Continue reading

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

We’re excited to share that an investigation by The Narwhal is a finalist for the...

A new documentary, Nechako: It Will Be a Big River Again, dives into how two...