Rocky Mountain coal mine in Alberta takes next step to expansion

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

Two days before Christmas, a Durham Region mayor penned a letter to Ontario’s minister of municipal affairs, asking for a favour.

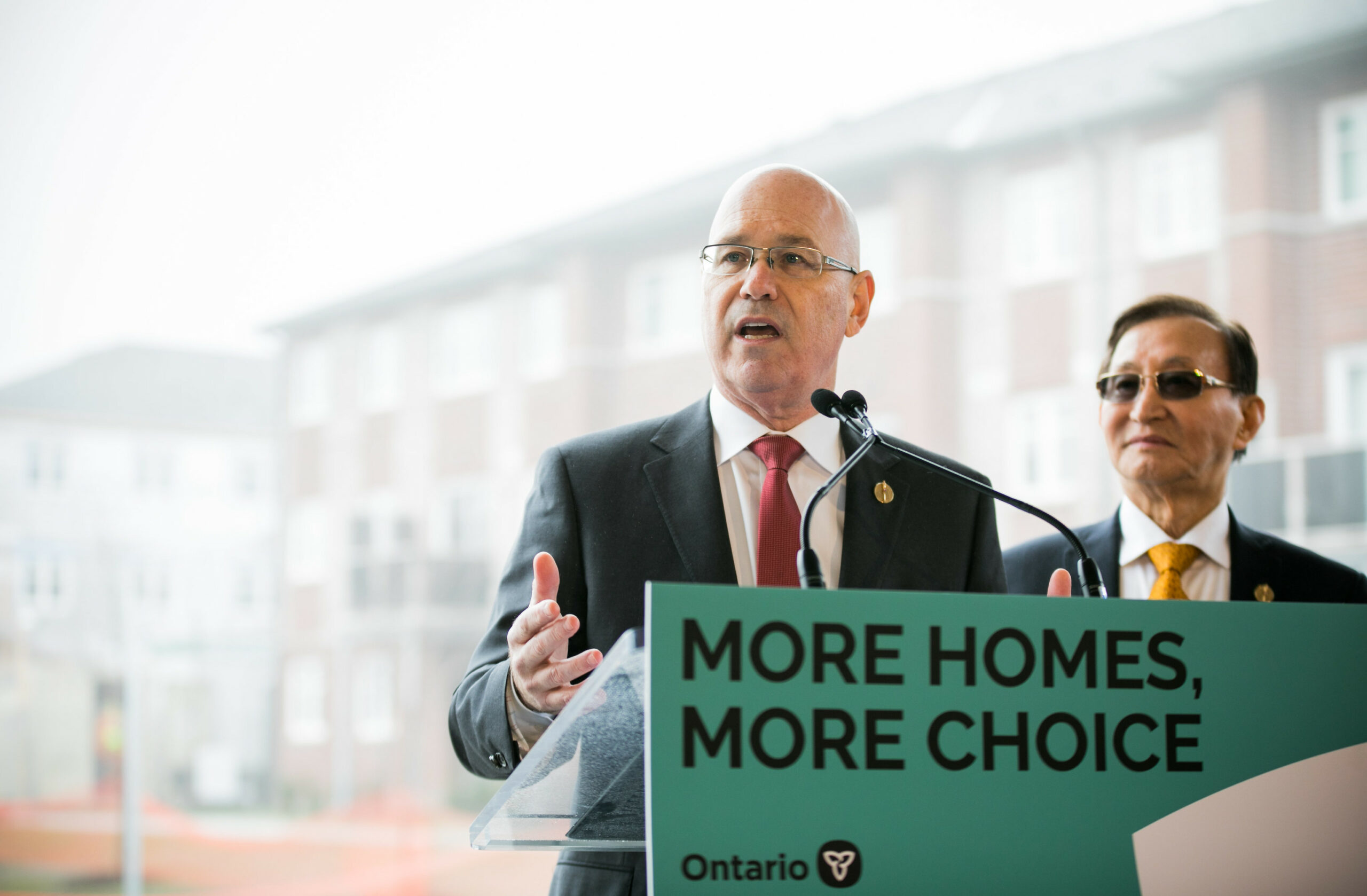

Kevin Ashe, the newly-elected mayor of Pickering, wanted Minister Steve Clark to use a controversial power called a minister’s zoning order, known as an MZO, to fast-track a major housing development in the city’s northeast.

“It will provide for more homes and more choices, faster,” Ashe wrote in the letter.

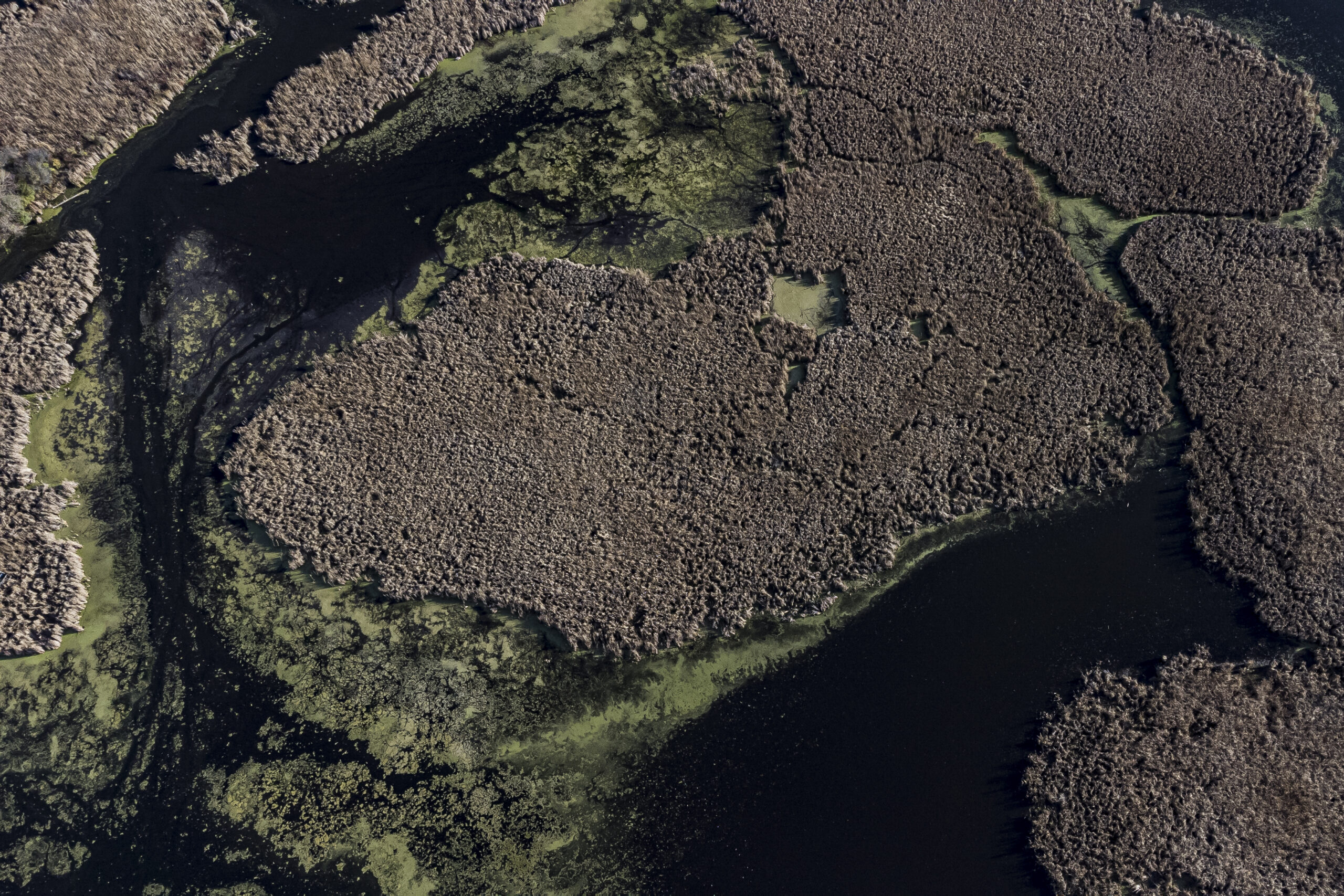

The land in northeast Pickering that Ashe was asking about is the headwaters of Carruthers Creek, a waterway that trickles down through the neighbouring town of Ajax to drain into Lake Ontario. Though parts of the creek further south are protected as part of Ontario’s Greenbelt, the headwaters aren’t, and critics say development there could cause big issues downstream.

Ashe’s letter sparked backlash almost immediately. That’s because his big ask taps into two long-running fights: the fate of the headwaters, but also the debate over the Doug Ford government’s use of minister’s zoning orders.

So what’s going on here, exactly? Here’s a breakdown of what a minister’s zoning order is, why they’re so contentious and what’s happening with the one Pickering has requested for the headwaters of Carruthers Creek.

In urban planning, rules around zoning define how a piece of land can be used — for agriculture, homes, stores or industrial facilities, for example. Zoning rules, typically set by municipalities, can even define how tall buildings can be.

If someone who owns a piece of land zoned for agriculture wants to build houses there instead, they have to apply to the municipality to have it re-zoned. That’s a long, difficult process. It often involves checking whether the re-zoning would comply with other land use plans, like provincial policies protecting natural features. And the public gets to weigh in before municipal governments make a final decision.

A minister’s zoning order, or MZO, is a mechanism the Ontario government can use to instantly override all of that. With a stroke of the pen, the minister of municipal affairs and housing can rezone a piece of land. This doesn’t give every single project all of the approvals it might need, but it does speed up the process, a lot. The orders also can’t be appealed, and the province isn’t required to consult the public before using one.

Minister’s zoning orders have existed for a long time, and previous governments have used them, too. In 2012, the Dalton McGuinty Liberals deployed one to relocate a grocery store in Elliot Lake, Ont. that was destroyed when a mall roof collapsed. Previous governments generally used them about once a year, for special circumstances. That was the original purpose of the mechanism.

That all changed under Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservatives, which have used the power at least 100 times since they were first elected in 2018, according to a government list. The previous Liberals used 16 of the orders over 15 years in government.

For years, Municipal Affairs and Housing Minister Steve Clark has said the orders are a pivotal part of the government’s plan to increase Ontario’s housing supply and create jobs. He’s also said that the province would never use a minister’s zoning order in Ontario’s Greenbelt.

Ford himself has said so, too: “We will never stop issuing MZOs for the people of Ontario, the people that need housing,” he said in 2021. In several cases, the orders have been used to fast-track important projects, like badly-needed long-term care homes.

Some Ontario mayors do believe the orders are appropriate when used correctly. Ajax Mayor Shaun Collier, for one, told The Narwhal he wants to bring forward a motion at council to ask the province for five minister’s zoning orders in his community, which he says would accelerate urban housing projects that include affordable units.

“I personally believe that MZOs can be a very effective tool when used in a responsible and predictable manner,” he said in an email. But using one on the headwaters of Carruthers Creek would be neither of those things, he added.

The Ford government has been criticized for using the tools in a way that doesn’t consider expert opinions, or for projects that are unnecessary. Sometimes, they’ve been used to kickstart projects on land that isn’t yet hooked up to municipal services like sewage and water, which city planners have argued doesn’t make sense. Like one issued in Clarington, Ont., in 2021 for land previously zoned as an environmental protection area, which wasn’t hooked up to sewers and water. And the mechanism isn’t necessarily being used for urgent projects, either — one 2020 order allowed a Walmart warehouse north of Toronto to be built on top of protected wetlands, while another that year was used to aid an entertainment complex in Pickering.

Other concerns revolve around transparency. There is no formal process for requesting a minister’s zoning order, Ontario Auditor General Bonnie Lysyk found in 2021. There’s also no established criteria for which ones get approved. Some orders have been made at the request of local municipalities, but some were against their wishes. And while some municipalities did public consultation before putting in a request, others didn’t.

Lysyk’s office looked at 44 orders issued between March 2019 and March 2021 and found many of them benefitted the same seven developers.

“Lack of transparency in issuing MZOs opens the process to criticisms of conflict of interest and unfairness,” Lysyk wrote.

In many cases, the orders have been used to override environmental protections while also lining the pockets of Progressive Conservative Party donors, a National Observer investigation found in 2021.

It’s also difficult to get clear information about each order, what they do and who requested them. The province has to post the orders online within 30 days, where they show up as regulations under Ontario’s Planning Act — but the text of the orders themselves don’t explain basic information about them, like the addresses of the development and who proposed it in the first place.

There’s also the issue of how such a volume of individual orders affects the bigger picture of environmental protection. Clark promised in 2021 to add two acres of land to Ontario’s Greenbelt for each acre of land developed using a minister’s zoning order. At the time, that meant the province would have to protect nearly 6,000 acres to make up for 3,000 acres of development, but Clark has handed down even more of the orders since then, so the current total is likely higher.

To date, the only land the government has announced it would add to the Greenbelt as part of the pledge is an 890-acre tract of forest north of Toronto that was almost entirely protected from development already. Clark’s office did not answer when asked for an update by The Narwhal.

The headwaters of Carruthers Creek are contested ground.

They sit in an area of land that’s part of the “whitebelt,”’ an unofficial zone between the Greenbelt and urbanized areas. There’s a lot of disagreement over what whitebelt land should be used for: some people view it as an important ecological buffer for the Greenbelt that should have been protected, while others see it as valuable land that was purposely left open for future development. Municipalities tend to make decisions about whitebelt land like the Carruthers Creek headwaters on a case-by-case basis.

A coalition of developers organized as the Northeast Pickering Landowners Group have proposed to build a community on the headwaters called Veraine. The landowners group didn’t respond to questions from The Narwhal for this story, but according to a 2021 Pickering city council document, its members include Dorsay Development Corp., Tribute Communities, Trinison Management Corp., Coughlan Homes, 2750 Hwy 7 Inc., the Brown Group and Armland Group.

Dorsay requested a minister’s zoning order for the area in 2020, but withdrew it after Durham Region, which includes both Ajax and Pickering, didn’t support the request. The developer group also offered to donate land to build a hospital on the headwaters in 2021, but a different site was ultimately chosen for the hospital, in part because of environmental concerns.

Those concerns are pretty serious, because developing the headwaters of a waterway affects everything downstream. There’s already a lot of urbanization along Carruthers Creek, and scientists have warned that more in the headwaters could lead to increased flooding downstream in Ajax. Stormwater management ponds could help with aspects of this, but scientists say they can’t fully replace the function of natural landscapes.

“Ajax council has taken a strong position against the development of the Carruthers Creek Headwaters and this position hasn’t changed,” Mayor Collier said in an email. He said he hasn’t seen any plans for stormwater management to go along with development in the headwaters: he doesn’t want his constituents at greater risk of flooding, but he also doesn’t want them on the hook for stormwater infrastructure costs.

The developer group has been making its case to the public, including through a form of advertising called sponsored content, which typically involves paying for an article marked as an ad to appear in a newspaper. In one sponsored story in the Toronto Sun, the Northeast Pickering Landowners Group argued that activists who oppose the Veraine project are contributing to overinflated housing prices. In a similar sponsored article in the Toronto Star, the group wrote that “experts,” including the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority, say the developers “will use responsible environmental measures to improve and protect the region’s ecological systems, including the Carruthers Creek watershed.”

The latter advertisement was misleading, according to the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority. Michael Tolensky, the chief financial and operating officer of the agency, said it hasn’t actually done a specific review of the Veraine proposal. The conservation authority manages Carruthers Creek, and its plan for the watershed included suggestions for a “series of mitigation measures to manage those impacts should detailed development proposals be considered by the municipality.”

Back in 2020, Ashe — then a city councillor and deputy mayor — was supportive of the original request for a minister’s zoning order on the headwaters. And in his letter to Minister Clark in December, he argued that the housing crisis makes it urgent for the province to accelerate the Veraine development. Durham’s population is expected to nearly double by 2051.

“If we accept the premise that we are in a crisis, which I do, then we must take bold action to get the issues of affordability and attainability back under control,” Ashe said in an email.

In his email, Ashe pointed to a broader process that’s also playing out: last year, Durham Regional Council voted to expand its urban boundary by opening 9,000 acres of farmland for development. The region is currently trying to figure out where that land will come from, and an initial proposal has so far included development on the headwaters of Carruthers Creek. That hasn’t been finalized, though, and some on the council are pushing for Durham to pursue denser development in urban centres instead.

Another dimension of the debate centres on whether Ashe’s request to Clark followed the right process. He didn’t consult Ajax before sending his letter to the province. Nor did he consult the Mississauagas of Scugog Island First Nation, a community 50 km northeast of Ajax that has ties to Carruthers Creek stretching back to the 1700s.

Mississaugas of Scugog Island Chief Kelly LaRocca doesn’t think it’s a good idea to “senselessly destroy the headwaters, risking negative impacts on the environment throughout the region,” she said.

“Once again, a government entity has refused to listen to potentially opposing views and missed out on an opportunity to advance reconciliation,” LaRocca wrote in an email, calling it “shortsighted.”

“Sound decision-making processes must look at impacts on future generations. In this case, one must consider the environmental consequences that will almost certainly lead to fiscal complications through extreme weather events and climate change.”

Ashe also didn’t put the request before the newly-elected Pickering council before sending the letter. He told The Narwhal his rationale is that council’s last recorded position on it, from 2020, was supportive of a minister’s zoning order. “Any discussions made outside of the council chambers do not change that,” Ashe said in an email.

Four Pickering councillors, a majority, have since said that isn’t a fair portrayal of their view and sent their own letters to Clark to ask that he deny Ashe’s request. Councillor Mara Nagy pointed out that Ashe sent his request right before the holidays while Pickering was in the midst of a massive snowstorm.

“I was shocked and I was a little bit almost hurt that we hadn’t at least been given a warning,” Nagy said in a phone call.

Other concerns revolve around the environmental impact. The developers have offered to add 465 acres of land to Ontario’s Greenbelt as part of the proposal, something Ashe’s letter said would “further efforts to build climate resilient communities.” The developer group hasn’t released where that land would be and who currently owns it, and Ashe’s office said it didn’t have details.

Phil Pothen, the Ontario environment program manager at the non-profit Environmental Defence, said the Greenbelt offer is a public relations exercise. It’s common for developers to offer up land they weren’t going to build on anyway while building on prime greenfield, he added.

“By actually destroying land that is functioning as farmland and habitat now, they’re causing a net reduction,” Pothen said.

Municipal Affairs and Housing Minister Steve Clark has stayed mum so far about Ashe’s request for a minister’s zoning order.

“We are aware of Mayor Kevin Ashe’s December 2022 request for an MZO,” Victoria Podbielski, a spokesperson for Clark, said in an email. “No decision has been made at this time.”

Podbielski didn’t answer when asked whether Clark is also considering letters from Pickering councillors who are opposed.

Pickering council is set to meet and talk about the issue on Jan. 23.

In the meantime, local group Stop Sprawl Durham has run a letter writing campaign. Critics have sent 1,000 letters to Ashe’s inbox, said Mike Borie, a founding member of the group. “It’s a never-ending fight,” Borie added.

Updated Jan. 25, 2023, at 10:05 a.m. ET: This article was updated to correct the name of the local group opposing Ashe’s request for a minister’s zoning order. The group is Stop Sprawl Durham, not Environmental Action Now Ajax-Pickering.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...