5 things to know about Winnipeg’s big sewage problem

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

The federal Impact Assessment Act, benign in name, has been fuel for intense anti-federal government sentiment in Alberta for years now.

The debate is now settled, at least in court, with the Supreme Court of Canada ruling with Alberta.

The act, perhaps better known to some as Bill C-69, gave the federal government the power to trump big projects — think coal mines, or oilsands projects — if it deems they are not in the public interest. It gained notoriety when it was dubbed the “No More Pipelines Act” by former premier Jason Kenney, and has been fodder for much political debate.

But it was not just a political weapon. Alberta also took the federal government to court. It saw success in front of the Alberta Court of Appeal, but was challenged in the Supreme Court of Canada.

That decision, out today, said “the federal impact assessment scheme is largely unconstitutional,” taking issue with the justifications for why certain projects are pulled under federal authority and questioning the government’s ability to use climate change and emissions to invoke the act.

But the court did reaffirm Ottawa’s authority to undertake environmental assessments as long as it doesn’t infringe on the constitutional division of powers.

Here’s a brief rundown on the latest:

Read on for everything you need to know to understand what this ruling means, starting from the beginning.

In the most simple terms, it is legislation that gives the federal government the power to review certain large industrial projects and to assess whether they are, broadly, in the public interest.

The current act is just the latest in a string of federal impact assessment regimes dating back to 1995 — that’s when the first iteration came into force under the Liberal government of Jean Chrétien. That act was overhauled seven years later under Stephen Harper’s Conservative government. That overhaul cut out some environmental impacts to be considered and public participation in the process.

When the Liberals were elected in 2015 under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, they set about overhauling that legislation (again) and the Impact Assessment Act was proclaimed in 2019.

“The way that the Harper government redesigned the federal assessment regime was to dramatically reduce the number of federal assessments every year from 5,000 to 6,000, to just a few dozen,” David Wright, a law professor at the University of Calgary, tells The Narwhal.

“And it’s lost on most people that the Trudeau government kept that core architecture. So what that means is very few projects trigger this regime.”

Wright said he’s wearing his “law prof at the University of Calgary hat” to provide context, but made it clear he also acted as co-counsel for one of the intervenors in favour of the act — the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment.

The projects that fall under the purview of the act are big, with thresholds that have to be met before a project qualifies — new large coal or oilsands mines, pipelines, highways and nuclear facilities are some of the examples. But the minister can also determine, based on their own discretion, that a project should be reviewed.

There are currently 32 projects winding through the assessment process, 20 of which are being assessed under the old legislation introduced by the Harper Conservatives.

The new act includes explicit references to climate change, social impacts, provisions for whether the project is in the public interest and, according to Wright, a “virtually unlimited, at least on paper, ability for everybody in the public — stakeholders, rights holders, etc. — to engage in the process.”

But that could change given the Supreme Court opinion and clarity will have to wait until the federal government amends the act to comply with the court’s opinion.

Speaking on Friday morning, both Steven Guilbeault, the federal minister of environment and climate change, and Jonathan Wilkinson, the federal minister of natural resources, said the act will remain in force and projects currently in the process will continue to be assessed.

But they said the government will implement changes to bring the act into compliance with the court’s majority opinion.

One central point that will have to be confronted is the court’s opinion on the issue of climate change.

“The court was fairly clear that greenhouse gas emissions and consideration of climate change impacts and commitments is not a basis for triggering of the act, nor for decision making with respect to these types of projects,” Wright said, speaking after the opinion was released on Friday.

“So whatever set of amendments come through, that will be a part that basically has to be trimmed out.”

While the Supreme Court found the portion of the act that establishes an impact assessment process for projects carried out or paid for by the federal government on federal land was constitutional, it took issue with the “balance of the scheme.”

In its opinion released today, the court found the “designated projects” portion of the Impact Assessment Act is unconstitutional for two overarching reasons. First, it found, “it is not directed at regulating ‘effects within federal jurisdiction’ as defined in the Act, because these effects do not drive the scheme’s decision-making functions. Second, the defined term “effects within federal jurisdiction” does not align with federal legislative jurisdiction.”

Chief Justice Wagner wrote, “[e]nvironmental protection remains one of today’s most pressing challenges. To meet this challenge, parliament has the power to enact a scheme of environmental assessment. Parliament also has the duty, however, to act within the enduring division of powers framework laid out in the Constitution.”

The court said the real issue is with the scope of which projects are pulled under federal authority and why.

“Perhaps more importantly, the court is saying all of that needs to be very closely and clearly tied to explicit areas of federal constitutional authority, like fishing, fish habitat, migratory birds, navigable navigation, and so on,” Wright said.

“So it’s not just about the projects, it’s about the scope of what can be taken into account in relation to those projects.”

Lisa Young, a political scientist at the University of Calgary, said in an interview, said she’s worried about the reactions of an Alberta premier who “takes her understanding of federalism and strategic advice” from a document called the Free Alberta Strategy, co-authored by the executive director of the premier’s office, Rob Anderson.

That strategy calls into question the impartiality of the federal courts. “If we go down the road of engaging in that kind of rhetoric, if we have senior officials engaging in that kind of rhetoric, we’re in a very difficult place because then we’re calling into question the legitimacy of the one institution that we have to interpret the constitution,” Young said.

“It puts us in an unprecedented and, I think, potentially dangerous place.”

It’s a worry that might be allayed given the opinion handed down by the court, but that doesn’t mean the road forward is clear.

The court avoided spelling out a path forward for the provinces and the federal government to sort out their differences on federal authority and impact assessments.

“Instead, at the very end of the majority decision, or opinion, they simply say we’re not going to prescribe a way forward, but we note that typically these things ought to proceed through cooperation between federal and provincial governments,” Wright said.

It’s something Wilkinson hopes to achieve.

“To the provinces and territories who brought this lawsuit forward, I would suggest that we collectively commit to this being the last time we look to settle our differences in court,” he said.

The Alberta government feels the same, although with some ultimatums.

“Finally, we call on the federal government to learn the lessons from this decision and abandon their ongoing unconstitutional efforts to seize regulatory control over the electricity and natural resource sectors of all provinces,” reads a joint statement from Smith and Minister of Justice Mickey Amery.

“Instead, we invite them once more to come to the table in good faith and work with Alberta to align our mutual efforts on emissions reductions and development of our electricity grid and world-class energy sector.”

Alberta has a long history of pushing back against federal authority. It, along with Saskatchewan, was denied control over its natural resources until 1930, despite both becoming provinces in 1905. The province tends to bristle at any hints that its authority might be curtailed.

This has led to various degrees of Alberta separatism over the years and the push for climate action has amplified anger in Alberta, which owes its wealth to revenues from the oil and gas sector.

Climate policies, including the assessment act, have led to calls for more autonomy for Alberta, including severing ties with the RCMP, pulling out of the Canada Pension Plan and the current government’s introduction of the Sovereignty Act, which it claims allows it to ignore some federal laws.

“This was the one of the first things that the Trudeau government did that sparked this kind of a reaction,” Young said.

In its submission to the Alberta Court of Appeal challenging the assessment act, the province called it a “Trojan horse” that will lead to further erosion of provincial authority and all but removes its hard-won control over natural resources.

Even in the wake of the Supreme Court opinion, the United Conservative government remains combative.

“The federal government, through passage of Bill C-69, and continuing now with their proposed electricity regulations and oil and gas emissions cap, is blatantly attempting to erode and emasculate the rights and authorities of provinces as an equal order of government under the Canadian Constitution,” reads the joint statement from Smith and Amery celebrating the opinion.

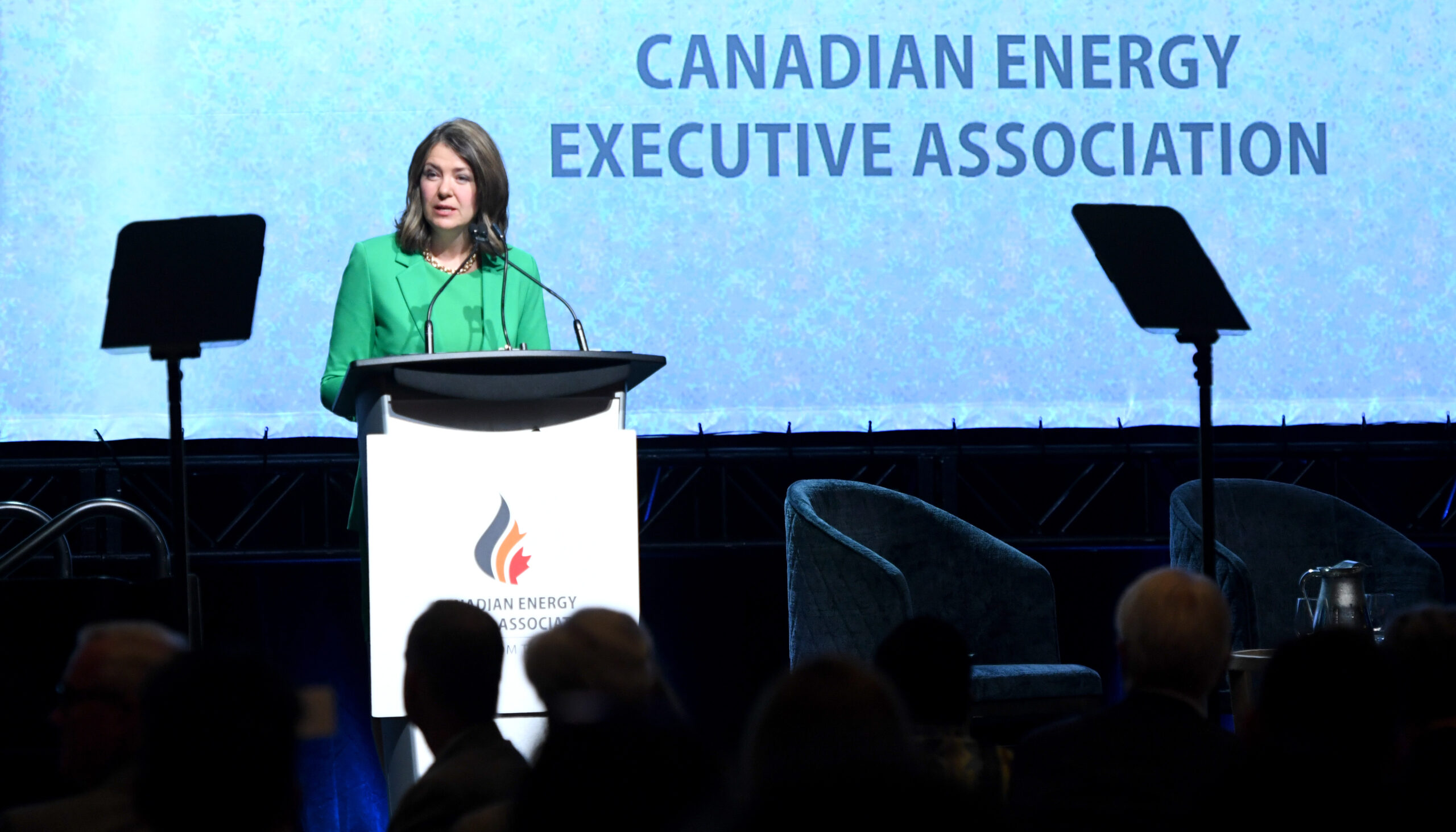

Smith, speaking at a news conference, blamed the legislation for killing billions of dollars in investment and the loss of thousands of jobs, but could not provide specifics when pressed. She then blamed the act for there being no natural gas projects lined up for approval.

“We’re a natural gas basin, we’ve got 12,000 megawatts of natural gas on our grid, why in the world, would I only have 41,000 megawatts of solar and wind in the queue and virtually no natural gas?” she said.

“That is absolutely underscoring why nobody wants to invest in natural gas in our province, and it is 100 per cent because of the uncertainty that the federal government created from this act.”

But it’s not just a battle of jurisdiction, it’s also simply a battle over wealth. Fossil fuels contributed approximately $25 billion to the provincial treasury last year. Without those funds, Alberta would not be able to spend as it does, or continue to forgo a sales tax.

Given the slow pace of assessments and the limited number of projects affected, it’s too early to tell whether it is more efficient or effective than previous iterations.

“The story is still being written,” Wright said. “We are still in time-will-tell mode. There aren’t a lot of examples.”

The federal government, for its part, has pledged $1.3 billion over six years to improve efficiencies in the process, but hasn’t yet released details. It also increased funding to regulator bodies to speed up the process.

The government says it will outline a concrete plan by the end of this year.

Alberta, for one, was not impressed when the act was introduced. Then-premier Jason Kenney dubbed it the No More Pipelines Act before it was even law — a rhetorical flourish he never tired of using — and promised to fight the legislation.

His government argued the act would give Ottawa a veto over projects under provincial jurisdiction and crossed a constitutional line by encroaching on what it sees as federal overreach.

It was part of a wider push against the federal government and its environmental and regulatory powers.

“I think it was understood as an attack on the resource sector, in Alberta and in parts of Western Canada,” Young said.

But beyond that, she said it struck a regional nerve and was seen by many as an attack on Alberta itself.

The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, the sector’s largest lobby group, said it would put Canada’s “economic future in jeopardy” and sacrifice “the livelihoods of hundreds of thousands of Canadians.” The industry group argued the process would take too long and the scope was too broad, which would spook investors.

Alberta wasn’t alone among the provinces, however. Ontario and Saskatchewan also vowed to fight the legislation and eventually signed on to a court challenge that started in the Alberta Court of Appeal and culminated in today’s Supreme Court ruling.

The Indian Resource Council, the Woodland Cree First Nation and the Alberta Enterprise Group — which was led by Smith at the time — were among the groups who signed on in support of the province’s appeal.

There was also support for the revamped legislation.

Ecojustice, which intervened in support of the legislation in the courts, celebrated what it saw as improvements to assessments and was “pleased that damaging amendments to the bill dictated by oil and gas interests were defeated and that the law maintains its ability to tackle crucial issues like climate change.”

The Mikisew Cree First Nation and the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation, both headquartered in Fort Chipewyan, Alta., both intervened in favour of the legislation, arguing it supported Indigenous participation. The Mikisew Cree argued the federal government has a role to play in examining impacts on Indigenous and Treaty Rights.

One thing that stands out in the 2022 Court of Appeal majority decision is its tone in a long introduction to its reasoning.

“The Impact Assessment Act also brings to the fore legitimate concerns about stranding oil and gas resources in this country as the world transitions away from fossil fuels to a greener economy,” reads the majority opinion.

“This transition will take time. That is why it is called a transition. That time may be measured in double digits, if not three or possibly four decades, particularly if carbon capture, utilization and storage, the use of hydrogen and small modular nuclear reactors allow those resources to be developed in, or near, a net-zero manner.”

Another stand out is its apparent departure from legal precedent — similar to an early opinion on the federal carbon price which was later upheld by the Supreme Court.

“Most folks who focus on the legal dimensions of this area would agree that precedent is on the side of the federal government here,” Wright said.

But he said this act does go further and there are open questions around just how far a federal government can go in applying assessments.

“I’ve been saying this for a few years now, this is short term pain for long term gain, and that gain is legal clarity,” he said. “That will really help the fog dissipate for probably decades to come.”

Ultimately, the court decided the act infringed on provincial jurisdiction and rights.

Updated Oct. 13, 2023, at 1:15 p.m. MT: This story was updated to include reactions from federal Environment and Climate Change Minister Steven Guilbeault and Natural Resources Minister Jonathan Wilkinson, Alberta Premier Danielle Smith and Justice Minister Mickey Amery as well as post-decision analysis by law professor David Wright.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...