Rocky Mountain coal mine in Alberta takes next step to expansion

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

Robert Bateman turns 90 today, and it will be a day like any other. He will wake up at 6:45 a.m., turn on CBC Radio and look out the window at the birds brunching at the feeders while he enjoys breakfast in bed (four scoops of yogurt, seeds and fruit, in case you were wondering). He will then reach for the binoculars his wife, photographer Birgit Freybe Bateman, tossed in the middle of their bed and see if there’s anything of interest in or around Ford Lake, which his Saltspring Island, B.C., property overlooks. By 10 a.m., he’ll be at his easel.

“Every day is the same as every other day,” he says from his studio the week before his birthday. “I virtually never get bored.”

Above the Rapids – Gulls & Grizzly, 30 x 48, acrylic on canvas, 2004

“Pacific salmon form an important part of the many bounties of North America’s wild west coast. Although I have not shown a salmon in this painting, you know that they are there. Some are in the quiet water above the falls and others are still fighting their way upstream. It is a far-ranging crime against nature and against ourselves to jeopardize the spectacular wild salmon.”

How could he? The iconic Canadian artist and naturalist has five to 10 paintings on the go and a long list of requests. Every year, he does between 10 and 15 major works, adding to the approximately 700 he’s completed in his career. He’s a member of nearly 50 naturalist clubs and conservation organizations and has been bestowed umpteen honours, including more than a dozen honorary doctorates. He donates his artwork and limited edition prints for fundraising efforts that have provided millions of dollars for environmental and social causes over the decades. The Bateman Foundation, a non-profit that connects people to nature through art, operates the Gallery of Nature, a permanent home for the artist’s work in Victoria’s Inner Harbour. The foundation also runs several programs and events in which Bateman is involved. Retiring has never crossed his mind.

Robert Bateman gets his wife’s opinion on a work in progress in 1997. “I’m lucky I’m married to an artist, Birgit, who has a good sense of taste. I like lots of opinions on my paintings. I’m not private about it. Part of family gatherings is coming to look at what grandpa’s working on. And then I’m interested in everybody’s opinions on it — even the grandkids.”

“I don’t know of any creative people that retire because their life is their art. It sounds a bit simplified, but that’s it,” he says as he sits at his easel, the morning light pouring in through the high windows of the cathedral-ceiling studio that was purpose built for him and Birgit. “My default position is to be sitting here with a brush in my hand.”

Today, that brush is painting a scene in Biddulph, a town in Staffordshire, England. It’s twilight, and a barn owl is cruising past a crumbling stone wall — all that’s left of a Catholic home that was pummelled with cannonballs during the English Civil War. The story behind the painting is perhaps as evocative as the work itself.

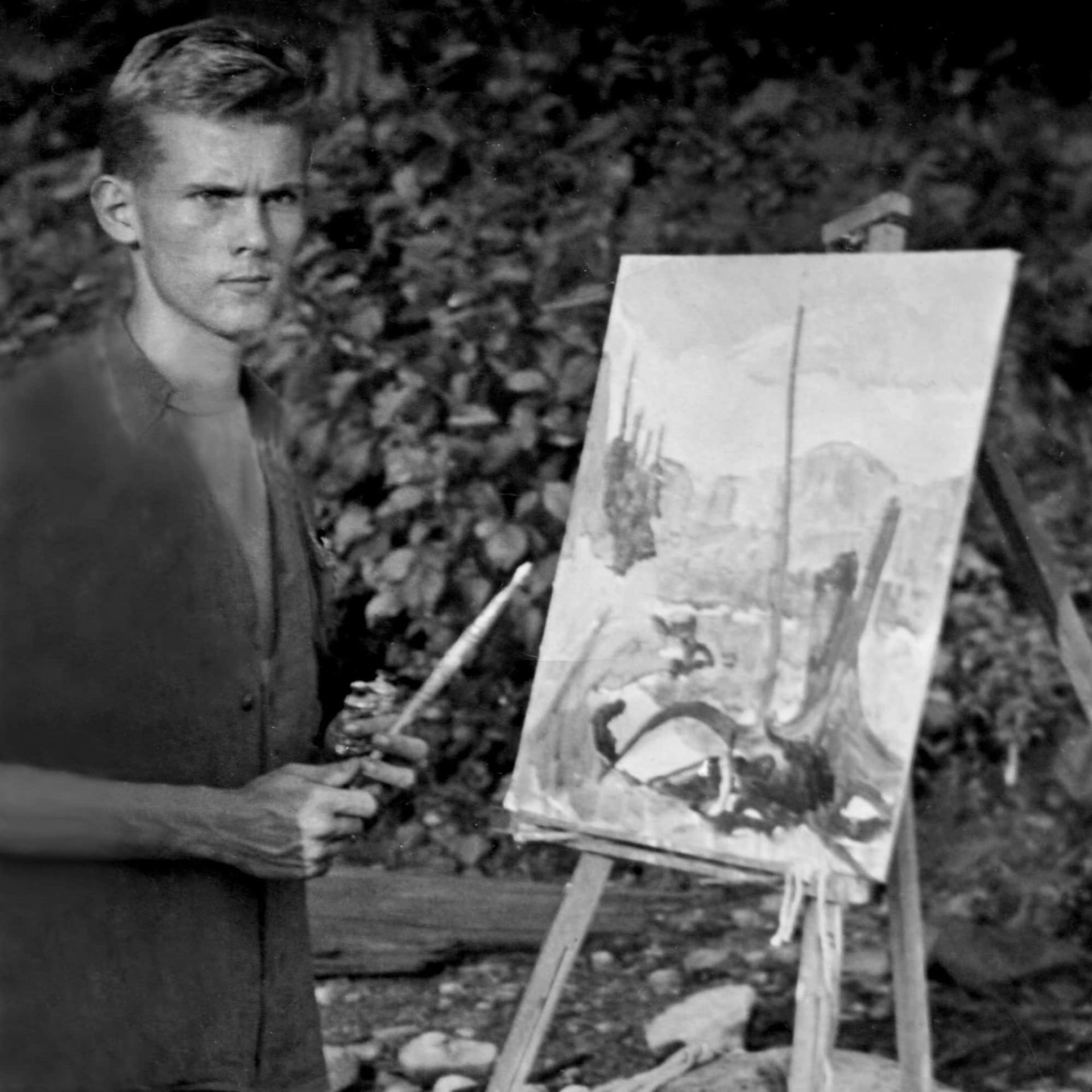

Robert Bateman spent four years working in Algonquin Park in Ontario in his late teens and early 20s. In his spare time, he painted en plein air like the Group of Seven. “All artists worth their salt paint what is in their heart, and what’s deepest in my heart is nature, especially mammals and birds.”

Robert Bateman is currently working on a piece inspired by a Victorian artist by the same name. “I work from photography — five to 50 photos for every painting. I record nature shows on TV and then sometimes for reference, which I’ve done in this case, I’ll play the show and freeze frame it. So, this is a freeze-frame TV barn owl flying by this old wall in northern England. The barn owl signifies wisdom.” Photo: Birgit Freybe Bateman

Several years ago, Bateman’s assistant, Kate Brotchie, was searching online for references to Bateman and came across a book entitled The Lost Pre-Raphaelite: The Secret Life and Loves of Robert Bateman, published in 2014. The book traces author and house restorer Nigel Daly’s attempts to uncover information about the scandalous life of Victorian artist Robert Bateman, who lived on Daly’s property. Birgit ordered her husband the book as a gift, and he devoured it. Today’s Robert Bateman had been aware of yesterday’s Robert Bateman and had even seen one of his pieces — a dead knight in a meadow at dusk with his faithful dog lying at his head — but had filed it away in the back of his mind.

“In the book, there’s a paragraph where Nigel Daly says they searched high and low for anything about this Robert Bateman, even to the furthest reaches of the internet, and they kept coming up with this irrelevant Canadian artist of the same name,” Bateman says with a laugh. “I read the book and enjoyed it so much, I wrote a fan letter to Nigel Daly: ‘I am the irrelevant Canadian artist and I absolutely loved your book. Could we come and visit sometime?’ So, we did, and that’s the setting of this painting.”

Robert Bateman has travelled around the world to see the species he paints in real life. Here, he hangs out with a friendly penguin in Antarctica. “To me, great art should have verisimilitude. It can be very loose and abstract, like Picasso, but it should still have the ring of truth to it and not look cooked up like a cartoon. When I teach workshops, I discourage doing art out of one’s mind. I believe in doing it out of one’s eye.” Photo: Birgit Freybe Bateman

The painting, entitled Barn Owl at Biddulph Old Hall, is destined for the Birds in Art exhibition at the Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum in Wausau, Wisconsin, an annual showing of the world’s foremost avian artists. Even prior to the pandemic, Bateman was planning to skip this year’s gathering but send a piece.

“I like to show the flag and show that I’m still alive and support the cause,” he says. “I also like to do it for the stimulation of doing something that is fresh and perhaps surprising — something other than a commission. I particularly like the way this one is going, so I’ll be happy to share it.”

Robert Bateman was a high school teacher for two decades before his art took off in the mid-1970s, and he decided to pursue it full time. “I’ve always been a teacher. One of the reasons I went into teaching was to share knowledge, excitement and joy. My art is a branch of that.”

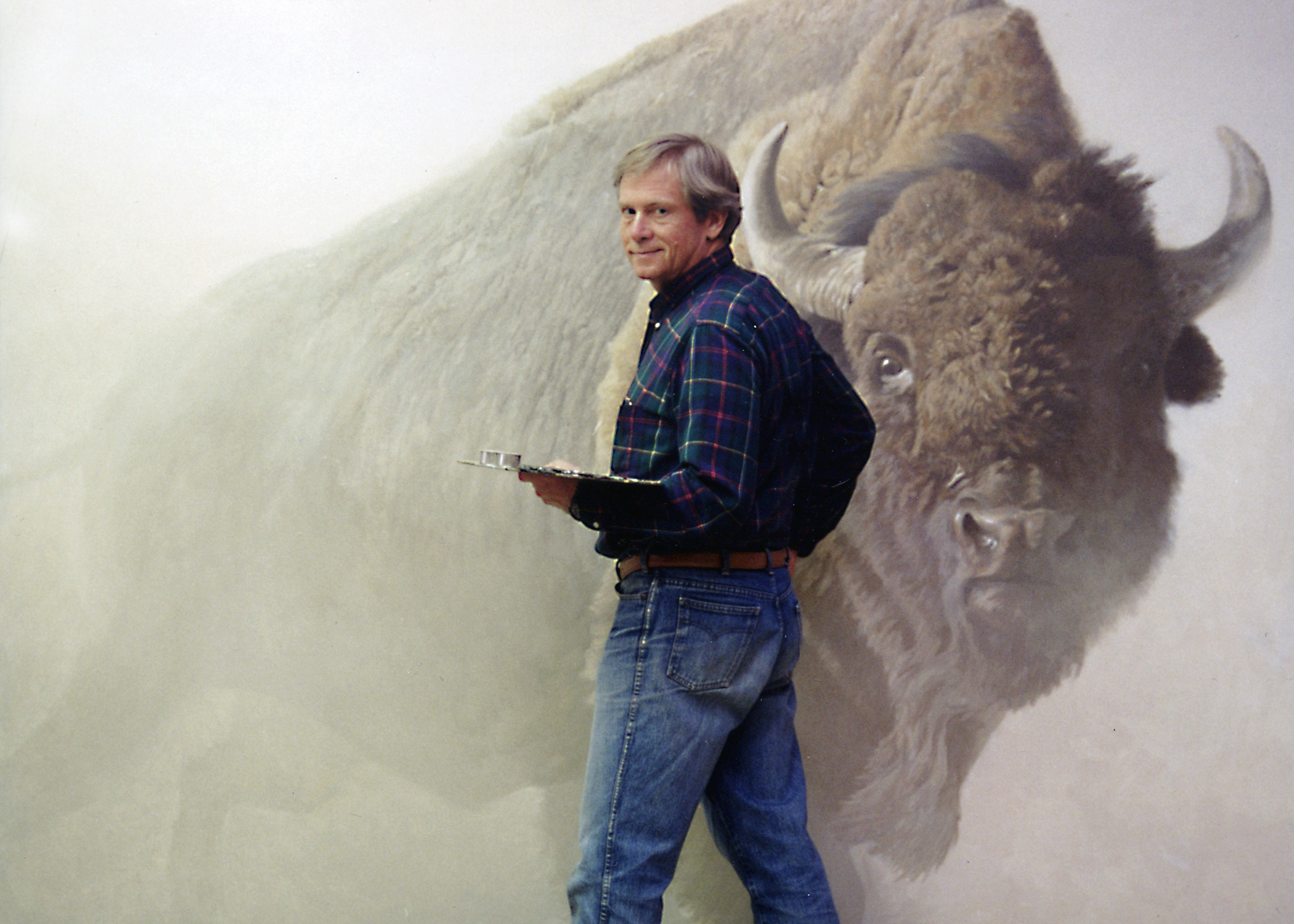

Robert Bateman works on Chief, a six-by-eight-foot canvas, in 1997. It was too large for his studio, so he set it up in an outbuilding. “We need to pay attention to the particularity of the planet. This is not just to save it. Paying attention to nature is a joy in itself and has measurable benefits for a person’s body, mind and spirit. Of course, nature art does not have to be detailed. It can inspire wonderful paintings in a variety of styles, flat or three dimensional, bold or detailed.” Photo: Birgit Freybe Bateman

The Return – Bald Eagle, Pair, 36 x 48, acrylic on canvas, 2001

“I started birding in the 1940s. At that time, we had certain bald eagle nests and sites to visit. By the late 1950s and ’60s, these disappeared due to the effects of DDT. In fact, the eagle was wiped out over most of its eastern range. Since DDT use in North America was banned in 1972, the bald eagle has become a hopeful symbol because the populations are springing back. There are, however, troubling signs for the future, once again due to human activities. This is one reason why I showed the male eagle returning to the nest without a fish. Industrial fishing is mopping up populations of herring, salmon and even less commercially interesting fish.”

If Bateman reaches an impasse on the barn owl painting today, he will likely move on to one of his other “front-burner” pieces. Perhaps the painting of 100 sandhill cranes on the Platte River in Nebraska or the scene of the winding Li River, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in China, with a fisherman in a dugout boat using a captive cormorant with a ring around its throat to catch fish, a practice that continues today.

He might glance at that long list of requests — a raven or a warbler, a crane sketch, a downy woodpecker, a pair of evening grosbeaks, a bald eagle’s nest with two bald eagles coming into it, a raccoon, a rabbit — and smile at the Leonard Cohen quote he jotted down while listening to the radio, albeit slightly inaccurately: “I’ve dealt a lot in various religions, but cheerfulness kept breaking through.”

Bateman always has several pieces on the go so he can pivot when artist’s block hits.

“I think of the muse up on top of Mount Olympus in Greece. She decides, ‘Well, Bateman’s been tortured enough. I guess I’ll reach out and touch him with my finger and give him a thought that he can carry on.’ Then the thought comes to me and I carry on for a while, and then kind of get stuck in the snow like I used to do in Ontario, so I start another painting.”

If the muse doesn’t reach out, he will likely stare out his window at the blooming heritage apple trees in hopes of a visitor showing up at one of his bird feeders to distract him, which, in fact, has just happened.

“A very rare and drab little bird has just arrived on the scene,” he says. “It’s a tit. I’ve only ever seen them once or twice in my life before this year. It’s a little grey job, a bit bigger than a wren.”

Queen Anne’s Lace & American Goldfinch, 11 x 16, acrylic on board, 1982

“The goldfinch is found all over North America in open country, particularly where there are weedy meadows and small trees. In a sense, the main subject of the painting is the meadow. It is an undistinguished little piece of the world, which we all too readily take for granted. In fact, meadows with their multitude of plants are often considered “wasteland” and are cut, or even worse, sprayed with poisons. My aim is to give a feeling of life, movement and air to this bit of nature. In a sense, I am glorifying a neglected corner of our planet.”

Bateman has been birdwatching since he was a teenager and welcomes the news that more people are trying it out during the pandemic. “If people change their behaviour and actually get out in nature and go for a walk in a park and go and sit in the harbour and look at the ocean, I think that that will make them better when this is all over,” he says, adding that he and Birgit get out for a hike on their property every day after lunch. “Just take some deep breaths — your cells rejoice.”

While he’s strolling through the bucolic land that surrounds his property, he’s taking note of the species he sees — and doesn’t see. “What I do myself and recommend other people do is get to know your neighbours of other species, and particularly get to know their names,” he says. “I think it’s insulting to say, ‘I love birds, they’re so sweet and cute, but I don’t want to know their names. It’s sort of like being a teacher and saying, ‘I love young people, but I don’t want to know their names.’ It’s superficial and it’s not engaging.”

Learning species’ names leads us down the path of learning more about them, Bateman says, and noticing troubling changes. “You can say to yourself, ‘How come I haven’t been seeing any fox sparrows for the last two years? What’s going on? Is there something going on in British Columbia or is there something going on where they migrate? And is it something I could get involved with by helping with a conservation cause?’ ”

Red-winged Blackbirds & Rail Fence, 36 x 48, acrylic on board, 1978

“In the early spring, the red-winged blackbirds move north to their nesting territory. I did field sketches of the birds and rendered plasticine models based on the sketches. Then I did paintings from the models on bits of card to the scale of the picture which had been roughed in. I tried the cutout birds in various positions using masking tape. This particular arrangement pleased me most, artistically. The fluffed-up bird on the left is the dominant one. The sleek bird in the upper right is the fleeing loser. After I had finished the painting an ornithologist friend informed me that the dominant bird would not normally allow himself to get below the subdominant bird. This scientific flaw bothers me, but not enough to change the composition. I always try to reconcile art and nature in my paintings, but if I had to choose between them, I would choose art.”

Departing Bonaparte’s, 36 x 48, acrylic on canvas, 2018

“One of our joys in life is vacation time with the family at our cottage on Hornby Island. This will most likely be the gathering place for our family for many years to come. Our boat is an inflatable zodiac. With it we take little expeditions to areas that are good for snorkelling. Returning from one of these trips we encountered a flock of Bonaparte’s gulls and tried to get close enough for photography. Often wildlife photos are of the back side of the creature getting away. I thought that this image made a good composition, capturing that moment of departure.”

Wildebeest, 30 x 40, acrylic on board, 1964

“The wildebeest is an odd creature. It has the face of a mule, the horns of a cow, the beard of a goat and the body of a horse. The rather freaky appearance is augmented by the fact that they will suddenly break into unexplained gambolling, almost like a bucking bronco. These animals occur in vast herds in East Africa. I have stood on a hill in Kenya and seen tens of thousands stretching to the horizon in all directions. Another evidently senseless bit of behaviour I have observed is that a procession of hundreds of animals will be walking single file following some unknown leader. The line, however, will wind in all directions, even going back on itself.”

That spirit of getting involved and helping out is another promising sign Bateman has seen in the wake of the pandemic. “There are thousands and thousands of inspiring examples of people tackling tough jobs and going in to help people and make the world a better place,” Bateman says, adding that we can do the same for nature.

The pandemic has postponed the birthday bash Bateman had planned with his family, which includes five children and 10 grandchildren, but he’s hoping to reschedule for the fall. “I’ve got to keep living and keep upright at least until that happens,” he jokes.

So, tonight will be a quiet one with his wife. “Birgit is one to make things special for occasions, so I’m not sure if we’ll have shrimp or crab or something more exotic.”

“You asked for roast chicken,” she calls from the other room.

Roast chicken it is. Followed by strawberry shortcake, one of Bateman’s favourite treats (with whipped cream and a couple of scoops of ice cream, in case you were wondering).

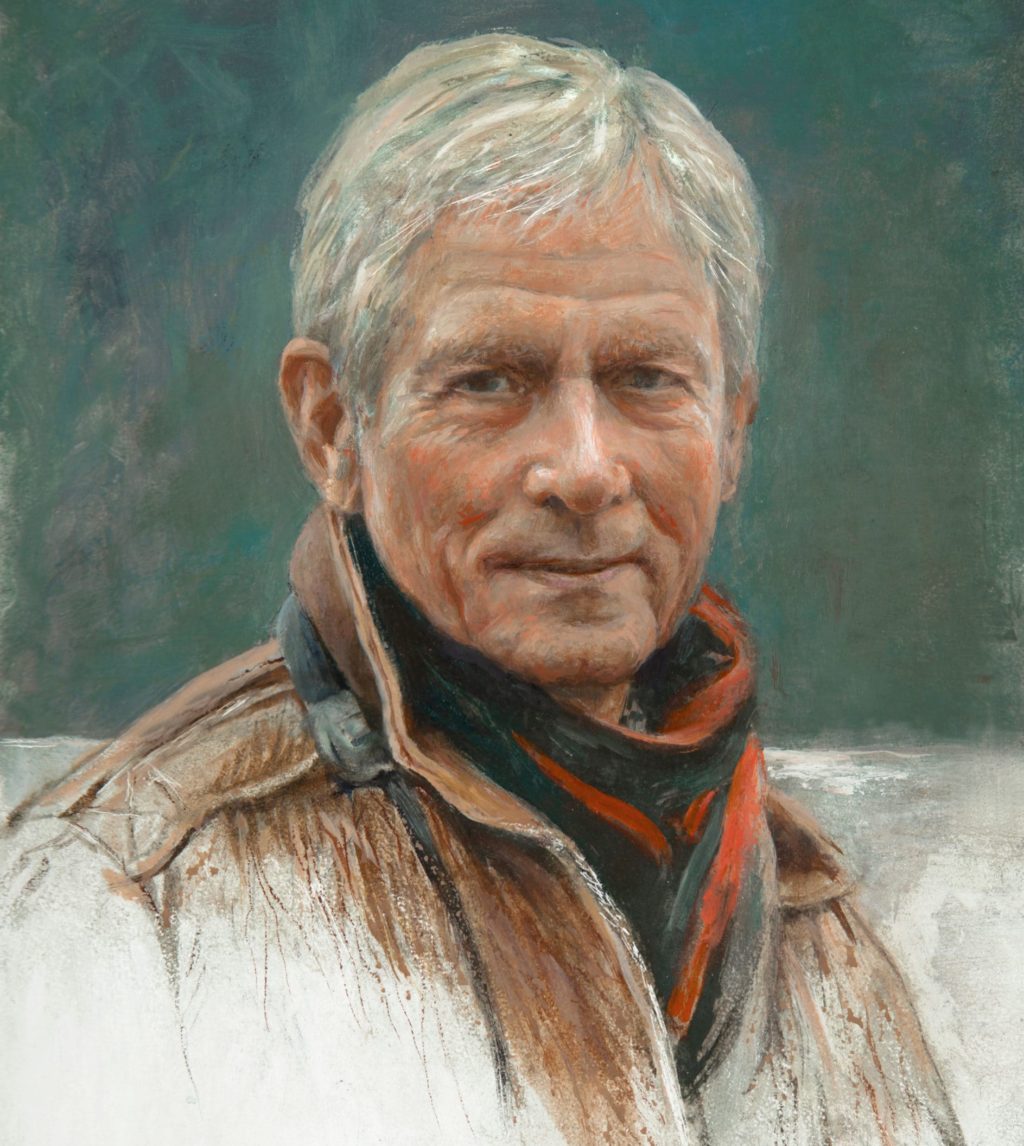

Self-portrait, 12 x 9, oil on board, 2015

“I love painting people. I’ve done more Homo sapiens than any other mammal.”

Robert Bateman canoes on Ford Lake, which is right next to his property on Saltspring Island, B.C., in 2013. “Becoming engaged with one’s place not only has personal benefits for body and mind, it has important benefits for the future of the place.” Photo: Birgit Freybe Bateman

After digesting over a British crime drama, it’s back to the studio until 10 p.m., just like any other evening. “I have a routine and I really like routine because I feel like I accomplish more.”

And for 90-year-old Robert Bateman, there’s still much to accomplish.

The new nonagenarian laughs when asked his secrets to a long, healthy, meaningful life before sharing this: “Find a piece of nature — could be a tree, could even be a dandelion — take a deep breath, smile and say thank you.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...