Rocky Mountain coal mine in Alberta takes next step to expansion

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

This is the first article in a two-part series. Read part two, featuring the voices of Indigenous activists in Edmonton, here.

When Alberta Premier Jason Kenney announced his government would be creating a “war room” during the spring election campaign, a local activist group, Climate Justice Edmonton, saw an opportunity.

Kenney’s war room — later rebranded as an independent corporation named the Canadian Energy Centre — would be allocated $30 million in government money to “respond in real time to the lies and myths told about Alberta’s energy industry,” according to the United Conservative Party (UCP) platform.

The day after the election, on April 17, Climate Justice Edmonton launched its counter-attack — an online fundraising campaign for “A ‘War Room’ to Beat Kenney’s War Room.”

The group’s initial goal was “30 hundred dollars” to combat Kenney’s $30-million investment in the war room. They laid out their plans: town hall meetings to work on a green new deal in Alberta, support for art and high school climate strikes and a “rapid-response fund to protect our allies and frontline communities as they come under attack from Jason Kenney’s politics of austerity and hate.”

As Emma Jackson, an organizer with Climate Justice Edmonton, tweeted at the time, “lots of $$$ = lots of chips = lots of well-fed organizers to stop pipelines and build a more liveable future for us all.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/BwXqYJKg5qv/

Climate Justice Edmonton organizers aren’t shy about their opposition to new pipelines and their calls to wean the province off fossil fuels, or the importance of recognizing Indigenous rights and the goal of creating a transition plan for workers in Alberta’s extractive industries.

As Climate Justice Edmonton members watched the donations roll in — $1,000, $2,000 — they realized the campaign was gaining traction. “Oh my god, we’re rich,” Jackson remembers thinking.

The group would go on to far exceed their “30 hundred” goal, raising nearly $20,000 for a “war room” of their own — and they’ve been busy ever since.

Climate Justice Edmonton isn’t the only activist group working on climate-related issues in Alberta. Groups like Beaver Hills Warriors, Indigenous Climate Action, Edmonton Youth For Climate and Extinction Rebellion Edmonton have all been active in recent months.

The Narwhal met with organizers with Climate Justice Edmonton to talk about their motivations, their vision and life in Alberta under the new UCP government.

Climate Justice Edmonton organizer Farid Iskandar says activism is the antidote to the flaws of electoral politics. “There is an inherently disproportionate power structure and the only thing that could stop the wealthy ruling class is for everyone else to get together,” he says. Photo: Abdul Malik / The Narwhal

Emma Jackson is advocating for a Green New Deal for Alberta. “This sort of, like, luke-warm, centrist politics is never going to be the answer,” she says. Photo: Abdul Malik / The Narwhal

Shortly after Alberta’s new government took power, it scrapped the province’s carbon tax scheme. Kenney had planned to celebrate at a gas station in Edmonton, but cancelled the event due to thick smoke cloaking the city from early-season wildfires up north.

The city was choking. Downtown buildings, normally visible from across Edmonton’s river valley, blurred in a grey haze, then disappeared. The end of the block disappeared. A not-small number of people donned handkerchiefs and masks over their noses and mouths. All of this, people were saying, and it wasn’t even summer yet. It was May.

Stephen Buhler, a 28-year-old volunteer with Climate Justice Edmonton, remembers that day well.

Stephen Buhler works as a machinist in Edmonton, creating parts for the oil and gas industry. He’s frustrated with the lack of climate action in the province, and has found joining Climate Justice Edmonton to be “the most rewarding work ever.” Photo: Abdul Malik / The Narwhal

“It went black,” he said. “It was our second coffee break and it got its spookiest.” Buhler was at his job in Edmonton where he works as a machinist supplying parts for the oil and gas industry.

“I was just dizzy and mad and furious,” he remembers. “I had so many emotions that day. I’ve probably never really experienced anything like that. I just wanted to shout at someone, ‘You got us here, how are you going to fix this?’”

At the same time, he knew, Kenney was cancelling the carbon tax. To him, it felt like a double slap in the face — like things were getting worse with the climate, and the province was doing even less about it.

“I was mad and defeated,” he tells me. “But I didn’t want to break down crying at work.”

Buhler already drives a Prius to the truck-filled parking lot outside the shop where he works, and had been worried in the past about how his coworkers would receive his left-leaning views.

He didn’t, he tells me, want to “get copies of the Edmonton Sun thrown at my head” in the break room.

Still, he says, “I‘m definitely not the only person in oil and gas who feel this way.”

Buhler, who comes from an oil and gas family, laments the fact that his job is linked to fossil fuels, but he knows that in this province, it’s the reality for many workers looking for jobs.

“What Alberta lives off of has created this,” he says of the early fire season. “In an ideal dream situation, we all just would have made wind-turbine parts that day.”

After work on that smoky day, Buhler went to a Climate Justice Edmonton meeting. “It was good to go there and be like, ‘okay, other people are worried about this too.’ ”

“You know we’re not going to fix this tomorrow, but we are going to fix it.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/B5gOH5iAWBe/

For Buhler, volunteering with Climate Justice Edmonton has been “the most rewarding work ever.” His role, he says, is to help wherever he can, whether it’s helping to paint signs or build art or organize an event.

“At the end of the day, I feel like I’m actually doing something worthwhile,” he says.

For the organizers The Narwhal spoke to, there are few other options. Activism is the main path forward they see — to get people together, and to have their voices heard.

For Farid Iskandar, this is a realization he came to after spending time working on political campaigns.

“I started my life and politics from the pragmatist electoral side of things and I’ve moved further to the left as I’ve gone along,” he tells me. “I used to think how we change power is you win government. Then you go in and do things.”

Now, he says, “I understand that, like, sitting in meetings with politicians and asking them to do stuff is not going to get you anywhere.”

“There is an inherently disproportionate power structure and the only thing that could stop the wealthy ruling class is for everyone else to get together.”

He’s concerned that this is true no matter what party is voted in — left or right, pro-labour or anti-union. “There are external powers that are going to be put up against them,” he says.

“You have to build the power outside of the electoral arena,” Farid Iskandar told The Narwhal. Photo: Abdul Malik / The Narwhal

Iskandar studied engineering in university, including a project focused on open-pit mining, and volunteered for Rachel Notley’s leadership campaign in 2014. As her time as premier went on, he became increasingly disillusioned with the decisions her government was making, particularly around the oil and gas industry and pipelines.

He was, as he would write in an op-ed in the National Observer, “dazed and disenchanted” by her leadership.

That led him to activism. “You have to build the power outside of the electoral arena,” he says now. “The electoral piece can only be, like, a small part of the strategy.”

That philosophy is part of why, in 2018, Iskandar and 11 others climbed the Ironworkers Memorial Bridge in Vancouver in the middle of the night and clipped themselves on to the structure’s sturdy steel trusses with carabiners and cables.

Activists climb the Ironworkers Memorial Bridge in Vancouver to protest the Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion. Photo: Tim Aubry / Greenpeace

They were there to send a message.

“I was, like, really scared before we got on the bridge,” he remembers. “I have a fear of heights.”

Seven members of the groups would suspend themselves from the bridge, dangling over the Burrard Inlet. They were blocking the route of an oil tanker waiting at Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain pipeline terminal to carry oil from Alberta across the ocean, while displaying art created by Indigenous artists. The rest were there to support them from above.

Activists dangles from the Ironworkers Memorial Bridge in Vancouver to block tanker traffic from Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain pipeline terminal. Photo: Greenpeace

Iskandar is now committed to activist movements at home in Alberta, and sees potential for a growing allegiance of workers and people concerned about the environment.

“We have a common enemy in Jason Kenney, so I’m hoping there will be more talk between labour and environment,” he says.

Climate Justice Edmonton has worked on a number of different actions to get their message across in Alberta.

One of them is known as bird-dogging — or showing up to political events and causing a disruption.

So when Justin Trudeau came to Edmonton in February 2018 for a town hall meeting, Emma Jackson was there with other Climate Justice Edmonton members.

It was, however, a bit awkward — she had a giant banner stuck in her pants.

It was a “nice silky fabric,” she remembers, but it was still tricky to smuggle into a crowded gymnasium packed with people and security detail.

That banner was one of three that Climate Justice Edmonton held up in the town hall, each with a message about the Trans Mountain pipeline, the climate and Indigenous rights.

Climate Justice Edmonton organizers hold up banners they snuck into a town hall meeting with Justin Trudeau in Edmonton in February 2018. Photo: Jason Franson / Canadian Press

As Trudeau answered questions about the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion, Jackson and others unfurled their banners behind him, much to the delight of photographers — the images appeared in papers across the country.

Jackson has a long history in organizing and politics. “My dad made me read the communist manifesto when I was in, like, grade nine,” she says.

She came to Alberta to do her masters in sociology — her research was focused on post-fire Fort McMurray at the University of Alberta. Jackson grew up in Ottawa — the daughter of a federal civil servant and a labour activist — and moved to New Brunswick for her degree.

Jackson came to Alberta to work on her masters in sociology, which focused on life after the wildfire in Fort McMurray. Photo: Abdul Malik / The Narwhal

She had long been developing a political identity that had little patience for centrism.

“This sort of, like, luke-warm, centrist politics is never going to be the answer,” she says. “So it demands that we put forward like a really bold vision of what we want the province to look like.”

Her vision is something of a Green New Deal — respecting Indigenous rights, ensuring a just transition for workers and ending the reliance on fossil fuels.

The banner that had been in Jackson’s pants — ”No Jobs on a Dead Planet” — went on to do something of a tour around Canada, displayed as concerned communities met to talk about pressing climate issues.

“That banner was in my pants,” she remembers thinking when she saw it in churches and halls across the country.

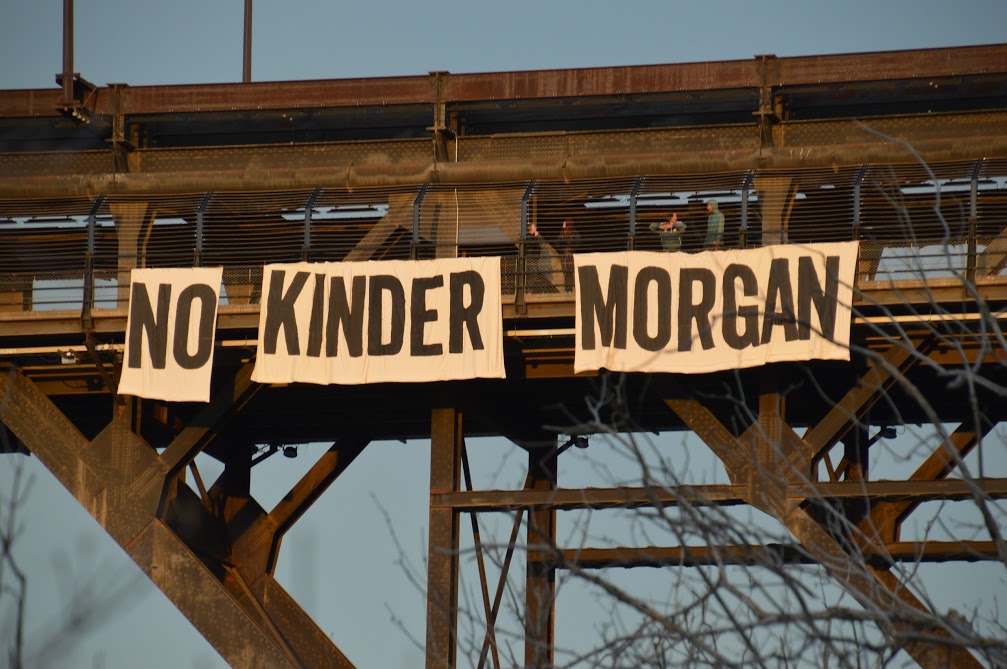

Climate Justice Edmonton was formally created in a group in January 2018, just a few months after they dropped a 50-foot banner over the North Saskatchewan River in Edmonton.

The banner, which read “No Kinder Morgan,” and dangled off the High Level Bridge, was a response to the pipeline politics in the province.

Climate activists look on from above after hanging a banner off of Edmonton’s High Level Bridge that connects the university area with the downtown core. Photo: Elauna Boutwell

A banner protesting the Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion hangs over Edmonton’s North Saskatchewan River in October 2017. Photo: Hannah Geldman

These days, Climate Justice Edmonton is at work on their latest action — delivering coal to Jason Kenney, UCP ministers and MLAs across the province.

“There are people from all across the province that are signing up to deliver coal to their UCP MLA offices,” Jackson says.

It won’t be real coal, of course. They’ve printed out what she describes as “shitty legislation” produced by the UCP and volunteers have used it to craft papier-mâché lumps of coal.

“We all have a really dark sense of humour,” Jackson says. “Especially with climate change it can feel so heavy and insurmountable to people that for us at a personal level we have no other option than to keep laughing.”

So when the internet recently stopped working at the house Jackson and others work out of, they joked it was the war room, imagining “the UCP broke in and stole our internet router.”

Humour has to play a role in climate activism, organizers say. Photo: Abdul Malik / The Narwhal

Though they can laugh about the antics of the UCP government, Climate Justice Edmonton members do worry about some of the tactics of the Alberta government

Jackson has been called out on Twitter on more than one occasion by the executive director of issues management for the Premier of Alberta, Matt Wolf, who has described her online as “someone who has worked to sabotage our economy.” (A spokesperson for the premier’s office did not respond to The Narwhal’s request for comment.)

“I struggle with it,” Jackson says of deciding how much to engage, or even follow, these sorts of tweets.

The first time Wolf tweeted about her, a friend forwarded her an email sent out by the UCP that she says included her name and photo.

“People know what your face looks like,” she says of having the governing party distribute her photo to its supporters, noting it was a time when the Yellow Vest movement was gaining steam.

“It is incredibly hostile,” she tells me. “In some ways I think it’s so desperate. It’s a signal that they’re losing.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/BwcjoQ-gpN-/

Overall, she’s perplexed by the UCP’s allocation of $30 million toward the Canadian Energy Centre.

“You claim to be fiscally conservative and you’re going to pour $30 million into, like, tweeting,” she says.

In mid-October, Climate Justice Edmonton sent out a tweet that would be seen around the world when it was retweeted by Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg.

“IT’S OFFICIAL,” read the tweet. “GretaThunberg will join a #ClimateStrike on Treaty 6 territory in amiskwaciwâskahikan.”

Thunberg would be joining a Friday climate strike in Edmonton, hosted by a coalition of local activist communities: Climate Justice Edmonton, Beaver Hills Warriors, Indigenous Climate Action, Edmonton Youth For Climate and Extinction Rebellion Edmonton.

From the moment she arrived, Thunberg attracted plenty of attention.

Estimates ranged from 4,000 to 10,000 attendees, swarming around the front steps of the Alberta legislature. The premier’s wing in the legislature, for its part, appeared to pull its blinds and leave up its signs proclaiming “I [heart] Canadian Oil and Gas.”

Edmontonians gather on the steps of the Alberta legislature for a climate strike featuring speeches from Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg, Indigenous activists and artists, and local climate activists. Photo: Sharon J. Riley / The Narwhal

It was a lot of work to organize. Climate Justice Edmonton only learned about the visit the week before, and had a lot to do: recruiting and training dozens of marshals for the march. Media requests coming in constantly. Booking the legislature.

All of this came at a particularly busy time for Jackson and others — only days remained before the October federal election.

Greta Thunberg’s “celebrity magnetism,” Jackson says, brought in a lot of people — and drew a lot of political interest.

Though the crowds were exciting, the sudden political interest was frustrating to Jackson. Politicians who “have never once reached out to any young climate organizers in this entire province,” she says, wanted to meet with Greta.

“You’re not actually meeting people doing things in your own community,” she adds — like the Climate Justice Edmonton organizers who have been ringing alarm bells about the climate crisis long before Thunberg arrived.

Each of the organizers The Narwhal spoke to was worried about the climate crisis, without a doubt. And the policies of Alberta’s UCP government — not just the war room, but also the public inquiry into the funding of environmental groups — has some of them more angry than worried.

“I don’t really get climate anxious,” Buhler says, describing a feeling that has become increasingly part of the modern lexicon. “I just get, like, climate enraged.”

But despite Climate Justice Edmonton’s early pronouncement of a “war room” of their own, they don’t see themselves as at war with regular voters — no matter who they voted for.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B5jN2WWAeaq/

“I don’t demonize people who voted UCP,” Iskandar says.

“I sympathize with them,” he says. “I think there’s actually a lot in common with people who shitpost me on Facebook — we’ve all been screwed by the same structure.”

In some ways, these are the same people the group is trying to reach.

“Climate Justice Edmonton tries to put forward the message that these are multi-billion companies,” who are active in the oilsands, Jackson says.

“Those companies ultimately care way more about their financial bottom line than they do about you and your family,” she adds.

They’re hopeful that this message will inspire more Albertans to pay attention to their vision for the future of the province — and the planet.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...