What’s scarier for Canadian communities — floods, or flood maps?

When maps showing areas most likely to flood are outdated, it puts people and property...

Jacinda Mack will never forget the day the tailings pond collapsed at the Mount Polley mine in her nation’s traditional territory, spilling an estimated 25 million cubic metres of contaminated waste into Quesnel Lake.

Once a source of drinking water and home to nearly a quarter of the province’s sockeye salmon, Quesnel Lake is still laden with the toxic tailings that spilled into its depths that August day in 2014. An underwater deposit of tailings, estimated to be about 600 metres long and a kilometre wide, rests on the lake’s floor where local residents worry it may be disturbed by upwelling.

For Mack, the accident marked an irrevocable change to the world she knew and transformed how she saw not only the Mount Polley mine but British Columbia, which she recognized for the first time as under siege by one of the world’s most powerful industrial forces.

At the time of the spill, the B.C. government was on a renewed mission to fast-track permits for new mines — some of which require tailings facilities many times the size of Mount Polley’s to be maintained in perpetuity.

There are lessons to be learned from the Mount Polley disaster that so far have fallen on deaf ears, Mack fears. Those who stand to learn the most from her experience are the small and mostly Indigenous communities currently being courted by mining companies across the province.

For the last several months, Mack, a member of the Xat’sull (Soda Creek) First Nation, has toured across B.C. with the Stand for Water tour, cautioning against the polished story mining companies often bring to rural towns hungry for jobs and economic activity.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

I think for a lot of people who haven’t been to the mine site it’s hard to grasp what the spill meant, but when I heard that the dam had collapsed, I felt sick to my stomach.

I opened up a video from the scene and I was almost physically ill. I started to cry, I was just like, ‘oh my god, what are we going to do?’ ”

I knew about the heavy metals, the processing chemicals, I knew about all of the treated waste and I knew about the force behind that tailings pond and that Quesnel Lake was down below.

It was a shock. All the communities around there when that happened had an emergency meeting. People were crying and talking about it like there had been a death.

We did a ceremony there on the banks of the Quesnel River in Likely. We did a ceremony you do in a time of grief, of great loss and that’s exactly how our communities were all feeling.

An aerial view of the Mount Polley mine disaster, August 2014, shows the mine’s collapsed tailings impoundment, with waste flowing past Polley Lake and right into what was the Hazeltine Creek. Photo: Cariboo Regional District via Youtube

There was this fear of the future…this grieving of the salmon, which were returning home. This should have been the time of year for celebration when the salmon were returning. People would normally have been preparing for that.

It was the complete opposite. Everyone stopped fishing, everything stopped. We weren’t getting information, people were angry and scared and hurt.

They were fearful that nothing was going to happen, that nothing was going to change, that there would be no consequences, there would be no justice.

“Here we are almost four years later and there haven’t been any charges laid by the government.”

I think people were getting really anxious: is anything going to be done or is the mining industry so entrenched, with such deep pockets that they can have a world-wide event — everyone in the world was watching Canada, this hub of mining in the world and this supposedly cutting edge mine has this major disaster — and nothing happens from it.

It’s like, ‘wow, how does that happen?’

I think that the industry is definitely powerful, definitely has deep pockets.

But I also think people are becoming more aware because of Mount Polley. They’re becoming more aware of those connections, more aware of those injustices and more aware of what’s in their watershed.

They saying, ‘oh hey, we’re downstream in southeast Alaska and there’s a proposal for 10 new mines in B.C. and one of them is built by the exact same company that failed at Mount Polley. Maybe we should look into this. Maybe we should be concerned. Maybe we should be asking questions and start talking to our neighbours about what their experience has been.’

That’s how I got drawn into the whole story, especially of tranboundary mines.

It started with me just sharing my experience.

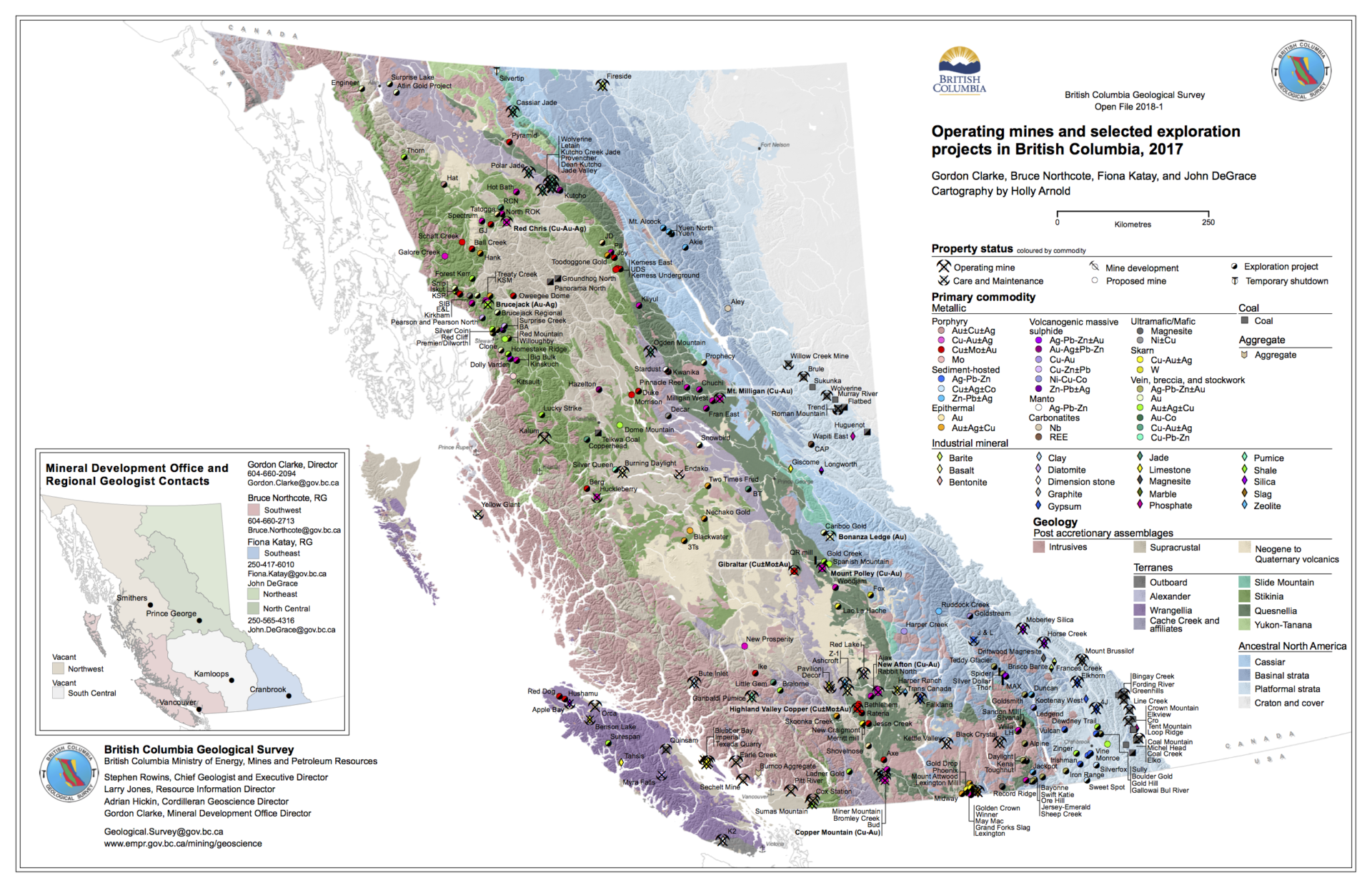

Active, proposed and terminated mining projects in B.C. as of 2017. Click to enlarge. Map via the B.C. Ministry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources.

I’m driven by communities needing to be informed about these lifelong, intergenerational decisions that they’re making.

I want them to be able to go in with their eyes open about what it is they’re agreeing to because a lot of time people don’t really understand what that full long-term picture is.

I think anywhere that I’ve spoken where they have a proposed mine development, I bring up a lot of things we’ve experienced that maybe they haven’t thought of because they haven’t had a major mine development in their area before.

I say, ‘make sure you ask about how much water they’re going to use. Make sure you ask about how water is treated because they’re going to be using water that needs to be treated at some point, especially if they’re going to discharge.’

I ask, ‘what are your values around water? Do you have a long-term water plan? Do you have a land-use plan?’

I also talk about something that’s been in the news recently, which are these man camps — these several hundred men that come into the community during construction phase of a new projects and how that shifts things in a community.

There was a report out by the Firelight Group with the Lake Babine Nation and Nak’azdli Whut’en that talked about local communities having to order in 200 rape kits to prepare for a new man camp.

It’s like, wow, that’s the mitigation? Not actually stopping the violence from occurring but just to deal with it with rape kits?

“Man camps really highlight a certain power dynamic at play. You have this often small and remote Indigenous community that’s out there and you have a big project that’s coming in and you’re flooding this area with people who have no connection to this place or these people, who are there short term, who are making a lot of money in an often impoverished place.”

When you’re dealing with rape and sexualized violence in that way it also speaks to the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women situation where Indigenous women aren’t valued in the same way as a non-Indigenous woman would be.

It speaks to this power dynamic, it speaks to racism, it speaks to the vulnerability of these small communities coming up against large multinational, multi-billion dollar companies.

And so it shifts your community in ways you don’t anticipate.

I think there really need to be an honest, inclusive conversation with people who are being impacted, with people who are coming forward with solutions for their communities.

Well when it comes to mining I think it’s important to hear a critical voice coming from an Indigenous perspective because there are different values.

It’s getting harder and harder for us to maintain our connection with the land because there is so much development.

Especially in the Cariboo there’s so much exploration, placer mining, there’s hard rock mines and so a lot of times we’re just locked out because of these mineral tenures and licences.

It’s harder to harvest, harder to hunt. We end up going further and further.

Quesnel Lake was our last stronghold and now the lake is being poisoned more and more every day.

And just different values too around what is seen as successful like, for example, having trout survive in a tailings facility. In 2012 I went to the Taseko Gibraltar mine and that was the first time I saw trout in a tailings facility.

Their tailings pond is huge, four times larger than Mount Polley’s. You can’t see from one side to the other.

And we saw all of these massive trout. They said, ‘look at how good our water is, you know, fish are more sensitive to the changes in water than we are.’

I said, ‘well do you eat them?’ And they said, ‘oh God no. We have our tailings facility restocked on a regular basis.’

And I was like, ‘well that’s the whole point isn’t it? That we have a healthy ecosystem that everyone can benefit from?’

I felt really bad for those fish. They’re living in a waste facility to prove a point for a mine rather than being in a natural environment with an opportunity of accessing actual clean water.

Worldview differences.

Jacinda Mack in Victoria to speak with MLAs about mining reform in B.C. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

It’s interesting that you say government is ‘setting the stage’ for industry, because that’s what happens now and has actually created a conflict of interest for government.

By that I mean, they’re supposed to be the watchdog but they’re also promoting industry.

Then you have the issue of professional reliance coming into this where you have companies basically watching themselves, doing their own testing, doing their own analysis and reporting and saying, ‘yup, we’re following all the rules!’

Until that whole system changes we won’t see the real accountability we need in communities.

Communities need to be more involved. I think we need Indigenous guardians, having Indigenous people on the land, who know the territory, who know the laws and protocols of their own people, who are then working with government and industry.

“I truly believe if we had Indigenous guardians in our territory and we had them watching Mount Polley, I honestly believe Mount Polley never would have happened.”

Because we would have held them in compliance. We would have reported all their problems.

The mine is only going to look at when they’re there and how much they can make. Their focus is immediate, on getting their resource out as quickly as they can while the markets are good.

We need to have a whole different conversation about how the land is valued, thinking about 20 years post-closure. What will that look like?

What is the highest value we have? In two generations, how will those values be affected?

Should we be looking at cumulative impacts of all of these industries on our water sources?

I think so. I think it’s madness not to look at the cumulative impacts because you’re making decisions completely out of context.

We’re not going to do a system-wide analysis of everything that’s going into this water. It’s very thread by thread with blinders on.

It’s not sustainable and it’s creating chaos.

There are definitely some opportunities within the environmental assessment review to look at ways of incorporating some of those social impacts, looking at the values, updating this point of reference, instead of coming at it from the point of view of the gold rush.

Let’s take stock of where we are now: what are the breaking points?

And let’s learn from Mount Polley and how we can prevent something like this from happening again.

Mount Polley is this crisis that is being wasted in a lot of ways. How can we change things for the better?

One change that would make a huge amount of difference is addressing the free entry system. Free entry really flies in the face of supposed ‘good faith’ consultations with First Nations.

The free entry system privileges mining laws over basically any other law.

You could be in treaty negotiations and in the final stages and still getting mineral tenures that are being purchased online by whomever, who’s maybe never been in your territory but they have a credit card and an online connection.

They can just pick up a mineral licence without any conversation or relationship with anybody. It’s just crazy. Zero consultation.

With the man camps, if that’s considered in the environmental assessment process that could be addressed. And we could look beyond just scientific data and models to other situations to say, ‘how can we learn from what has already happened?’

Right now there are no financial assurances to make sure the site is being taken care of over the long-term in a way the community deems as proper.

Every mine should have a disaster response plan.

There shouldn’t be total discretion over every single mine site saying, ‘oh this mine is going to have a $14 million bond but this one is only going to have a $7 million bond.’

The financial assurances piece is really important and land-use planning is really important, so you can get ahead of the curve — even before a project is developed, you know if a community will support a project or if they consider that a no-go zone.

That’s where you can address Indigenous rights and the principles of Free, Prior and Informed Consent and support the Indigenous guardians.

These things really need to be considered within the environmental assessment process.

That could change this relationship where industry is monitoring itself to really restoring and balancing that power, giving it back to communities that are impacted.

I feel like the industry drives at this incredible pace, it’s so fast. It’s hard to keep up to a company that’s got three engineering companies employed, a whole team of lawyers, they’ve got their executives and whatever and you’re one person.

“When I was in Soda Creek I was one person in a community that didn’t receive any funding to address consultation and permitting responsibilities. I felt like a mosquito trying to hold back the tide.”

But now stepping back from the front lines and looking at it from a different perspective, I can see there is a lot of work being done by a lot of people.

There are these intersections between groups that are working to protect clean water, saying water is life.

They want government to follow through with their promises and they want there to be consequences.

We as communities and Indigenous peoples need to get in front of that conversation to say, ‘this is what we mean by Free, Prior and Informed Consent, here is our land plan, here are our guardians.’

To me that would be a really exciting future because it would be inclusive, it would be community-based. There would be more power sharing, more economic opportunity for people.

Maybe I’m utopian in my view but I feel like things would be a lot better if more people had a say and had more ownership over these decisions.

Part of the new story where we are now is talking about this new generation of Indigenous leadership coming up. I am super stoked on this new generation because they’re even stronger, smarter, faster, better than me.

Our identity is shaped by the land and now my genetic line, my children and their children will have to be dealing with the Mount Polley mine for the rest of their bloodline.

But we are not defined by this disaster, we’re defined by how we respond to it and what we do, how we activate others, how we lead and share.

Indigenous communities are connecting, even across borders. I think even a year from now that’s going to be a stronger, a bigger, wider, deeper story.

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

When maps showing areas most likely to flood are outdated, it puts people and property...

We’re suing the RCMP for arresting a journalist on assignment for The Narwhal. It’s an...

As glaciers in Western Canada retreat at an alarming rate, guides on the frontlines are...