Hope for a huge, ancient and imperilled fish

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

Even before my mother was arrested I knew the day wouldn’t go as planned.

The night before, I slept on a worn couch beside a steadily fed fire in anticipation of the early morning arrival of RCMP officers. They were coming to enforce an injunction and break up a camp positioned near the bottom of a forest service road at the north end of Kootenay Lake, near Kaslo, B.C.

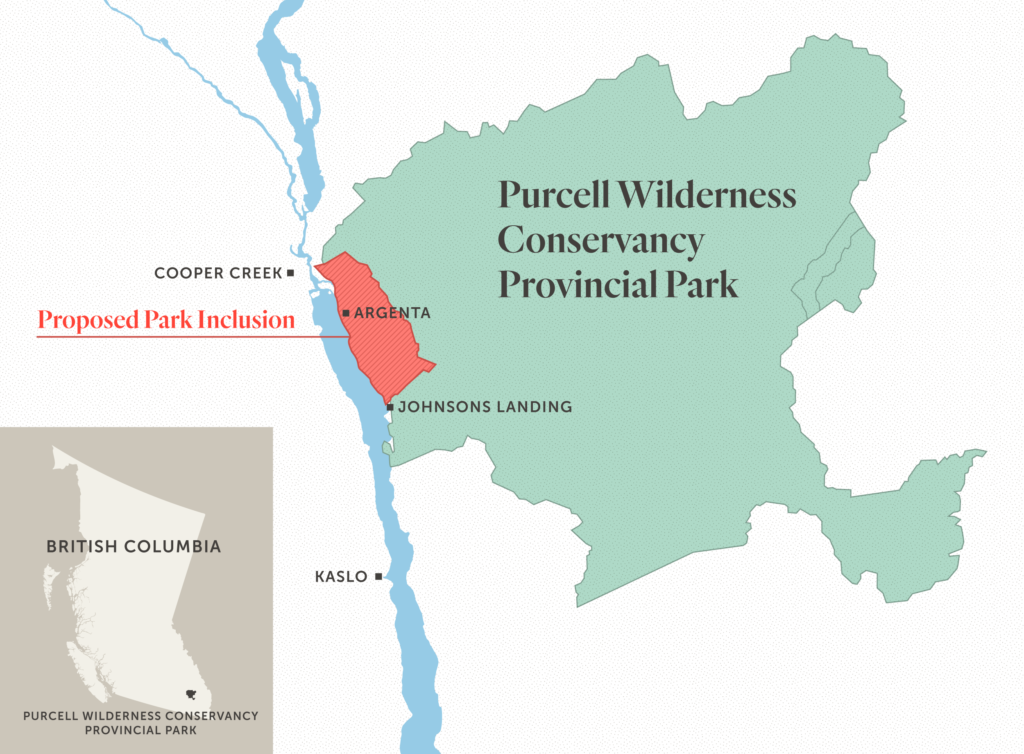

It was being occupied in an effort to protect a 6,200-hectare strip of forest surrounded by a provincial wilderness conservancy. Parts of the area, known as the Argenta-Johnsons Landing face, were set to be logged by Cooper Creek Cedar Ltd. in April. Due to the occupation, three weeks had passed without a chainsaw or feller buncher roaring to life.

I was there as a photojournalist to document what happened, but it’s a place I know intimately. I was born in a small cabin surrounded by these forests, in the 150-person village of Argenta, B.C. The management of these trees has been a point of community contention my entire life. Many residents have pushed to have this forest included in the Purcell Wilderness Conservancy, which surrounds it on three sides, while companies push to log it. But this camp was something new.

Grouse Camp — named after the frequently heard accelerating wing beats of the ruffed grouse — was started by members of Last Stand West Kootenay, a group of environmental activists dedicated to protecting old-growth forests. Many of their members lived in the nearby city of Nelson and a handful of them had participated in the Fairy Creek protests last year.

Knowing that logging was imminent, the camp was erected on April 25. Throughout the 23 days leading up to that brisk May 17 morning, visits by RCMP from the nearest detachment in Kaslo and the RCMP’s Division Liaison Team — a specialized group of officers who act as mediators between protesters and industry — were regular occurrences.

According to Miguel Pastor, a member of Last Stand West Kootenay, while the RCMP repeatedly stated there was an injunction in place, they also made it clear that “if you’re peacefully protesting and not blocking the road, then you will not be subject to arrest.”

In the morning, I organized my camera gear and notebooks and was ready to document what was about to unfold between police and protesters.

As people began to arrive, a circle was formed around a newly lit fire near the entrance of the Salisbury Forest Service Road. Songs were sung, accompanied by a lone drumbeat. One person put themselves in a sleeping dragon — a buried mass of concrete that a person’s wrist can be clipped into through a piece of PVC tube. Later, another person would follow suit.

Police officers gathered at the bottom of the road shortly after 8 a.m., approaching the roughly 35 people, about 20 of which were local residents from Argenta and Johnsons Landing. There were also a handful of children. An RCMP helicopter circled overhead.

The script they thought would be followed, the one both sides had often read from at Fairy Creek last year, disappeared. The negotiations between appointed police liaisons and commanding officers, used to determine where peaceful protesters could and couldn’t be, didn’t happen. The rules of the game had changed. A loudspeaker blasted a pre-recorded message stating anyone blocking the road was liable to be arrested under an injunction written almost three years before.

“Usually there’s some representative from the police who speaks with some representatives from the protesters and they sort of agree to what’s going to go down,” explains David Tindall, a sociology professor at UBC who has studied anti-logging protests for two decades.

Tindall is “surprised” by the approach taken by the police, though he says there are no hard and fast rules when it comes to these kinds of enforcement. What plays out is often a “function of who the actual officers are and what their background is,” which means that similar situations can have very different results.

Shortly after the message on the loudspeaker stopped, the camp’s appointed police liaison became the first arrested, followed closely by the legal observer. Later on, officers did allow one man who was there with his four children to leave but no one else was given the opportunity.

“It’s brutal that people got arrested that had no intention to,” says Noah Ross, a lawyer who is representing many of those arrested. “It’s scary and [there’s] a lot of stress and expenses.”

My mother was the fifth or sixth taken away after asking to leave while standing on the shoulder of the road. I bit my tongue, took a photo of her hunched, 75-year-old body being escorted away, and scribbled in my notebook.

She had gone to the camp that morning to bring two dozen eggs to the people there and show her support for “the young people who were there who believe in protecting the ecosystem of my backyard,” she says.

When the 30 person enforcement team arrived, along with a helicopter and drone, she says she began to feel uncomfortable and decided to leave. “I went to the front and said I needed to go home,” she says. “They told me no one was going anywhere and when I asked for the supervisor Sgt. Brady came and told me I couldn’t leave. Before I knew it, they arrested me.”

In total, 17 people were arrested and charged with civil contempt of court. When asked by The Narwhal why people who had no intention of blocking the road were arrested, the RCMP replied in a statement that “those arrested were observed or located on the road during the enforcement action,” and had “opted not to depart prior to the enforcement team’s arrival.” They also noted the narrow nature of the road, saying it does “not allow people to peacefully protest off the roadway and not impede operations.”

Bill Kestell, woodlands manager of Cooper Creek Cedar Ltd., was asked to comment on this story and said he has “no comment.”

Because Cooper Creek Cedar Ltd. applied for the injunction, it is up to them to bring the charges to court, otherwise they will be dropped.

In recent years, as logging plans have moved forward, the push to include the Argenta-Johnsons Landing face in the conservancy has gained momentum.

Mount Willet Wilderness Forever, a group of local residents lobbying for the protection of the Argenta-Johnsons Landing face, drew the attention of Suzanne Simard, a professor of forest ecology at the University of British Columbia who lives in nearby Nelson. Earlier this year, four of Simard’s students conducted a study comparing five-year-old clearcuts above Argenta with the proposed cutblocks on the Argenta-Johnsons Landing face. Among the findings was data showing the intact forest sequestered 20 times more carbon than the clearcuts.

Because of this, Simard says, when you cut down an old-growth or primary forest like the one found on the Argenta-Johnsons Landing face, you create a positive feedback loop that escalates both deforestation and climate change.

Through logging, the natural carbon sequestration of trees is lost while also emitting carbon through the hastened decay of the forest floor and short-term products like toilet paper or pellets made from the harvested timber, Simard explains.

“This adds to the global pool of carbon dioxide that is forming around the globe and causing the greenhouse gas effect,” she says, “which in turn exacerbates issues like wildfires and insect infestations, leading to more deforestation, reinforcing the positive feedback loop.”

According to a 2019 report prepared by Jens Wieting for Sierra Club BC, B.C.’s forests began emitting more carbon than they stored in the early 2000s. The report also questions the provincial government’s carbon counting system when it comes to carbon emissions produced, whether from industry or wildfire, by its forests, stating that “uncounted forest emissions are now often greater than the total amount of emissions that are actually counted.” Both Simard and Rachel Holt, another Nelson-based forest ecologist, find the government’s approach to forest carbon emissions archaic and puzzling.

“[Climate change] is beginning to overwhelm society in terms of the effects we’re seeing in B.C. firsthand,” says Holt, who was appointed to the Old Growth Technical Advisory Panel by the provincial government in 2021. “Yet we’re still not taking it seriously.”

Holt doesn’t believe clearcut logging in B.C. has a place in the new paradigm outlined by the Old-Growth Strategic Review, whose 14 recommendations were adopted by the provincial government in 2020. “We should not be disturbing the soil, we should be maintaining carbon stocks, we should be keeping the biggest trees and managing for more resilient, open forest ecosystems that can withstand fire … and we really don’t do that at all,” says Holt.

When Simard presented the findings of her study to the Selkirk’s district manager of forests, she says she felt the paradigm shift, where forests are managed for ecosystem health rather than timber value, isn’t being understood or implemented by those directly managing forests.

“They just don’t get that we need to be saving these places because they’re absolutely crucial in the carbon cycle issue and that carbon and biodiversity are tightly linked together,” she says. “If they understood the intent better they would have different prescriptions but they don’t understand the intent.”

In response to questions, a representative from the district manager’s office told The Narwhal to speak with the Ministry of Forests. The Ministry of Forests did not respond to requests for comment.

While Holt sees the logging plans laid out for the five cutblocks on the Argenta-Johnsons Landing face as “not being the best and not being the worst,” when it comes to retaining trees and protecting old growth, she doesn’t believe the plans go far enough. “We need to really do this right.”

Thanks to its geography, Holt and Simard see the Argenta-Johnsons Landing face as a biodiversity hotspot. Its position at the north end of a large lake, along with its connectivity between high and low elevation and wet and dry forest, makes it the perfect migration corridor for wildlife.

Because of these attributes, she sees protecting the Argenta-Johnsons Landing face as both a necessity and an opportunity to enact the paradigm shift the province has verbally committed to.

“All the ingredients are here. It’s right beside a park, it’s got endangered species, it’s got an informed citizenry, it’s got a First Nations presence. It should be a place we can save.”

When Grouse Camp was born, a sacred fire was lit by Chiyokten, a man from the W̱SÁNEĆ First Nations, with the blessing of Sinixt matriarch Marilyn James. In many Indigenous cultures, including the Sinixt whose traditional territory encompasses the Argenta-Johnsons Landing face, the lighting of a sacred fire sets an intention for a ceremony or action.

“Usually a fire is lit around an intent or a purpose like protecting those cutblocks,” says James. “It’s a thing to be honoured, respected and taken care of, always with that intent in mind.” Once lit, it must be tended 24 hours a day until the action or ceremony comes to an end.

Last Stand West Kootenay is settler-led, but they say they look to uphold the land declaration announced earlier this year by James and fellow matriarch Taress Alexis, stating that all resource extractions must cease until consultations with the Sinixt are carried out and consent is given.

The Sinixt were officially declared extinct in Canada in 1956 for the purposes of the Indian Act, so issues around their traditional territory, and who needs to be consulted by those wishing to operate on it, have become convoluted. Last year, the Sinixt, who are recognized in the U.S., won a Supreme Court of Canada case, affirming their constitutional right to hunt in their ancestral territory in Canada.

James, Alexis and others reside in Canada, where the band continues to be unrecognized and therefore do not legally need to be consulted. For the Argenta-Johnson Landing face, consultations by Cooper Creek Cedar Ltd. did not include the Sinixt.

The goals of the Grouse Camp, according to those who created it, were three-fold: stop immediate logging; create awareness around the Argenta-Johnson Landing face and its proposed inclusion into the conservancy; and apply pressure on Cooper Creek Cedar and local government officials with the objective of initiating a meeting between them, the Autonomous Sinixt, Last Stand West Kootenay and Mount Willet Wilderness Forever to negotiate the area’s protection.

According to Ross, who is also representing land defenders arrested at Fairy Creek, the RCMP’s approach to land defenders has changed in the last decade. He’s observed an increase in the use of exclusion zones — areas where members of the press and legal observers are denied access in the name of creating safe work areas for officers.

In April of 2021, Justice Thompson of the B.C. Supreme Court granted an application brought forth by a media coalition, including The Narwhal, to amend the injunction in place at Fairy Creek because he felt the RCMP had used unnecessarily large exclusion zones to hinder press accessibility.

On May 17, I was twice moved beyond lines of sight to where enforcement was taking place at Grouse Camp: once when they were extracting a woman from a sleeping dragon and once when two women were being handcuffed and the situation appeared to be escalating. In both instances I was moved roughly 50 metres away. When asked about these exclusion zones, the RCMP offered a written response stating that “officers have the right to work in an area that is safe. Where and how large those safety zones are will be dictated by operations.”

Ross sees this as an escalation in tactics by the Community-Industry Response Group and believes that the arrests of people wishing to peacefully protest were unlawful. “It sounds like there were a couple of arrests of people in hardblocks, which were reasonable,” Ross says. “But I don’t know that any of the other [people] were properly arrestable under the injunction.”

Ross says the same troubling approach was taken in November on Wet’suwet’en territory. “It seems like there’s a culture of non-accountability to civil liberties within [the Community-Industry Response Group], where they’re willing to kind of go beyond the injunction in order to try and break a camp,” adding that extending that to a small blockade in the Kootenays just seems “completely out of historical tradition in relation to rural forests.”

Pastor, a member Last Stand West Kootenay, agrees this is an escalation but views it differently.

“It’s highly disturbing that this group of people can act with complete impunity … for the right of industrial extractivism, but I would like to say that this is just a continued legacy,” he says.

“What’s changing now is that the settler population is waking up to the reality that this current mode of society is unsustainable and now that they’re starting to take action for these things that Indigenous people have defended … since time immemorial, they’re realizing the role of the police increasingly to be the enforcers of the destruction of land and water.”

Meghan Beatty, one of the two women extracted from sleeping dragons during the raid, says she is left with no choice but civil disobedience.

“I’m a pharmacist, I have my doctorate, I’m a stepmom of three, I’m a tax-paying citizen of so-called Canada,” she says. “Yet I have been driven to the point that the only way I think anybody will listen to me is by locking myself into the earth to physically block people from going in to commit further ecocide.”

Ross doesn’t believe the RCMP’s escalated response to environmental protesters will stop acts of civil disobedience. “There are strong movements that are going to keep growing and that’s, unfortunately, going to lead to more conflict,” he says. “Without public policy change, policing isn’t going to stop these kinds of direct actions.”

Holt, the forest ecologist, agrees that without governmental action, incidents like what happened at Grouse Camp will become more common.

“[People] have been offered a paradigm shift but they’re not seeing it,” she says, adding that the funds spent on enforcement could be better used to find common ground between industry and activists. “Why don’t we put that [money] into the solution bucket instead of into the enforcement bucket. Sending the police in to maintain the status quo is not going to help us move forward.”

At 10:45 a.m., after the last person was carried away, I was escorted down the road by two officers. By noon, the camp and all its infrastructure was cleared away. Thousands of dollars worth of personal belongings, including car keys, cellphones, tents and musical instruments, were destroyed and taken to the dump. The sacred fire was extinguished and beyond the din of logging equipment driving up the mountainside, a ruffed grouse beat its wings.

At the end of my interview with Simard, I asked, as most journalists do, if there was anything else she’d like to add.

“I think that people need to know that there are [solutions],” she replied. “The earth is such a resilient place that if we can do the right thing, it will heal itself. We can recover the carbon stocks, we can recover biodiversity, because…the whole system is built to recover and I think people need to know that hope is there. That’s why we’ve got to fight now.”

In the evening of May 18, a community meeting attended by 33 people was held at the Argenta community hall. Each person, most of whom were present when the Community-Industry Response Group moved in, shared their experience. Shock, rage and sadness were all present but above all there was a strong sense of resilience.

“After what I saw yesterday, I felt like all my hopes and dreams for my children and grandchildren were shattered,” said one woman who had fled through the forest to avoid arrest. “But this is giving me hope.”

“Well, yesterday was all about breaking us,” someone else added. “It’s clear to me tonight that they absolutely failed.”

Three days later another circle was formed, this time in a clearing a few hundred metres from the Salisbury Forest Service Road. Sinixt matriarch Marilyn James led the ceremonial lighting of another sacred fire, offering fistfulls of tobacco to the flames with each prayer spoken. When all the tobacco was gone, she added a large bag of cedar boughs and the fire came alive, flames dancing to the crackling song of needles igniting.

Editor’s note, June 9, 10:15 a.m.: A previous version of this story stated that as people arrived two people placed themselves in a sleeping dragon. The story has been edited to reflect that the second person did not put themselves into a sleeping dragon until later in the day.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. Angello Johnson’s shoulders burn, and his arms...

Continue reading

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

We’re excited to share that an investigation by The Narwhal is a finalist for the...

A new documentary, Nechako: It Will Be a Big River Again, dives into how two...