Danielle Smith says separation is about alienation. It’s really about oil

The Alberta premier’s separation rhetoric has been driven by the oil- and secession- focused Free...

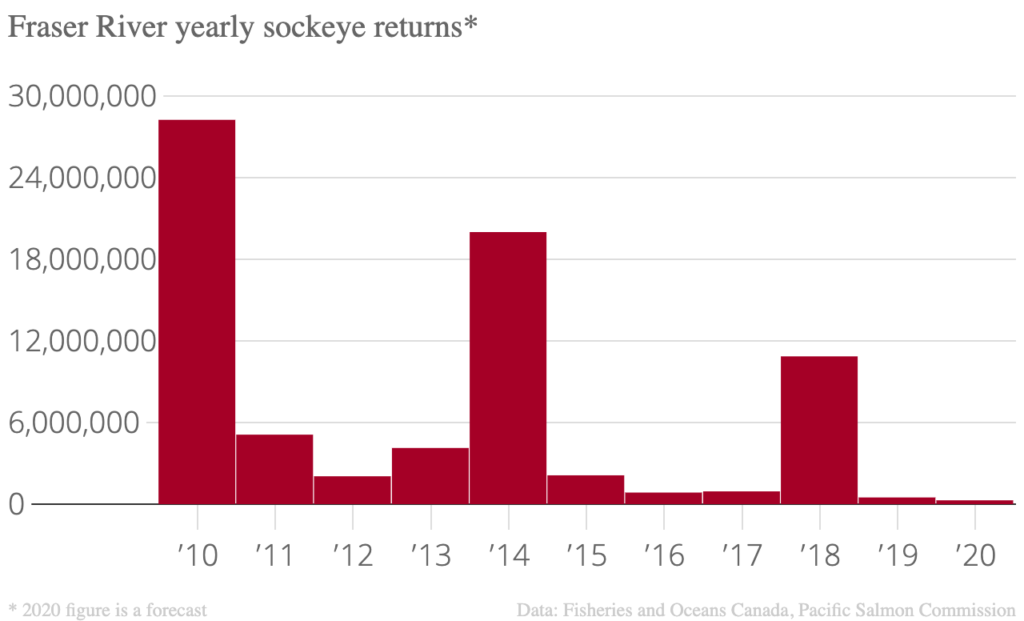

Scientists at the Pacific Salmon Commission knew 2020 wouldn’t be a great year for Fraser River sockeye salmon — but they didn’t know it would be this bad.

Returns of adult sockeye averaged 9.6 million between 1980 and 2014, ranging from two million to 28 million per year. The commission predicted just 941,000 salmon would return this year.

But returns have been so low this summer, the commission had to update that projection in early August. It now expects only 283,000 adults will return, which would be the lowest return ever recorded.

Fraser River sockeye salmon return to spawn in the river where they were born, sometimes within a few metres of where they hatched. Most spend two years in freshwater and two years in the Pacific Ocean. They typically return between late June and October.

Scientists base return estimates on the number of salmon that were born four years earlier. That means when returns are lower than expected, salmon went missing somewhere during their four years in the ocean.

Tyrone McNeil, vice-president of Stó:lō Tribal Council, said he thinks 283,000 is still a high estimate. He’s disappointed by what he sees as a lack of proper response from Fisheries and Oceans Canada Canada.

“I’m really disillusioned,” he said. “[Fisheries and Oceans] doesn’t seem to be alarmed in any sense.”

Chief Wayne Sparrow of Musqueam Indian Band echoed his disappointment in the federal department’s response to suffering salmon populations.

“I’m hoping the department will do something. Or else, we will be telling our grandkids that there used to be salmon in the Fraser River,” he said.

“I don’t think it’s too late, but we’re at five minutes to midnight.”

Salmon are at the centre of many First Nations’ ceremonies and histories, and are integral to their food security. Children have inherited fishing practices from their parents and grandparents for millenia. But when there are no fish, they lose that opportunity.

Sockeye have been suffering due to a multitude of factors, including overfishing and climate change, which has caused warmer waters than the salmon are used to. Including the Pacific Salmon Commission’s latest expected return for 2020, three of the last five years will have had record-breaking low returns for Fraser River sockeye.

Chart: Arik Ligeti / The Narwhal

Fisheries and Oceans Canada has taken actions to protect salmon, including implementing a

new Fisheries Act that reinstated some protections stripped by the Harper government and launching a salmon restoration and innovation fund that commits $142 million over five years to restoration projects in B.C.

But salmon advocates are calling for bolder action like tougher restrictions on harvesting salmon, better monitoring of fisheries and recognition of Indigenous fishing rights.

“We’ve recommended so many things to [Fisheries and Oceans] over time and they’ve never been implemented,” said Tracy Wimbush from Siska Nation, who is fisheries program manager for Scw’exmx Tribal Council.

“These threats have all accumulated and here we are today with a collapse of our fisheries,” she said. “How many years do we have to hear this is the lowest number we’ve seen up to this point?”

Here are some of the challenges experts say Fraser River sockeye salmon are facing.

Migrating salmon pass fish farms, and those fish farms are often infested with sea lice, which can latch onto the migrating salmon. Sea lice suction onto the fish and damage their fins and scales, inflicting wounds and causing bleeding.

For juvenile salmon just a few inches long, a few lice can mean “they’re dead,” McNeil said.

Biologist Alexandra Morton, who has been studying the impact of sea lice on wild salmon for years, has found higher death-rates in salmon infected by sea lice. In one of Morton’s trials, almost 98 per cent of juvenile pink salmon with a mature louse died.

Craig Orr, founding member and conservation advisor for Watershed Watch, has been researching the impact of sea lice on fish since 2001. He worked on the Cohen Commission

, an inquiry into the decline of Fraser sockeye that was completed in 2013. He said the inquiry identified three major drivers of sockeye decline: climate change, competition with hatchery pink salmon and salmon farms, which he called “lice factories.”

The Cohen Commission issued 75 recommendations, one of which called for the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans to prohibit net-pen salmon farming in the Discovery Islands of B.C. this fall, unless they are “satisfied that such farms pose at most a minimal risk of serious harm to the health of migrating Fraser River sockeye salmon.”

The Fisheries and Oceans website claims the department has met 100 per cent of the Cohen recommendations, and notes the department will complete a disease risk assessment process on salmon farms this year. If it finds farms pose “more than a minimal risk,” the department promises “salmon farms in the Discovery Islands will be required to cease operations.”

Earlier this year, the federal Liberal government backed away from its campaign promise to phase out open net pen salmon on the West Coast by 2025.

Orr called the department’s claim to have met all of the Cohen recommendations “fiction.”

“If [Fisheries and Oceans] were serious about protecting wild fish, they would … get the farms out of migration routes,” he said. Orr advocates for farms to be moved on land.

Climate change has led to warmer river and ocean temperatures, which have many negative impacts on salmon. Warmer waters mean more California sea lions on B.C.’s coast which, along with a booming seal population, means salmon are facing more predators, Sparrow said.

The warming sea also means less of the zooplankton that salmon rely on for food.

Catherine Michielsens, the Pacific Salmon Commission’s chief of fisheries management sciences, said salmon at lower latitudes in B.C. will have “difficulty remaining viable” because of increasing water temperatures.

High temperatures in the river cause stress in fish and salmon can die before reaching spawning grounds. Changes in precipitation, causing periods of drought followed by heavy rain, can trigger events like landslides, which damage freshwater habitat. Michielsens said habitat restoration and banning salmon harvest still wouldn’t be enough to save salmon in the face of climate change.

“How much we will be able to change their downhill trajectory will depend on how successful we are in curbing greenhouse gas emissions,” she said.

“Even in low-emissions scenarios, it’s not likely that all salmon populations will remain viable.”

Salmon are also losing habitat due to industrial activity. The Fraser estuary has lost 70 per cent of its salmon habitat, which juvenile salmon rely on as they adapt from fresh to saltwater. Conservationists are concerned about a number of industrial projects proposed for the lower river, including the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion, the expansion of the Tilbury LNG plant, and Roberts Bank Terminal 2, a container terminal that will destroy 177 hectares of salmon habitat.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada forecasts salmon returns every year in order to develop fishing plans prior to the season, according to the department. As salmon return, data from test fisheries, hydro acoustic counters and environmental information are factored in to adjust fishing plans.

The department said it does not expect a Fraser River sockeye fishery this year.

But McNeil and others think large-scale, long-term pauses on fishing will be necessary to save salmon and understand how they are doing year-to-year without the stress of harvesting.

“If we don’t know the numbers, we shouldn’t be fishing them,” McNeil said.

“Everyone will have to bite the bullet, at least for a little while,” Sparrow agreed. Allowing salmon populations to recover, he said, could mean pausing harvesting for three to four years. Others have advocated to only allow harvesting near spawning grounds rather than at sea, to ensure enough fish make it back to spawn.

Conservationists have advocated for more selective harvesting practices to be introduced, like fish traps and live capture, so fishers can focus on stocks in greater abundance and not catch fish from struggling stocks. They’ve also called for better monitoring of fisheries to enforce best practices, including the use of surveillance cameras.

Orr wants to see the government fulfill all recommendations of the Cohen Commission, and stop acting as a salmon farming regulator and promoter “at the same time.”

Last year, the federal government signed the Fraser Salmon Collaborative Agreement with 76 First Nations in B.C., promising to include First Nations in conservation and management decisions. But Wimbush said First Nations are still experiencing “parental oversight” from Fisheries and Oceans Canada and haven’t been involved in any decision-making.

“Fisheries and Oceans was set up to push out First Nations from the fisheries and allow the colonizers more access to the fisheries, and it has worked really well over time,” she said.

The Big Bar landslide, discovered in June 2019 but thought to have happened in 2018, “blocked virtually all of the natural migration of the Fraser sockeye” until late August 2019, according to a study by Fisheries and Oceans Canada. The slide devastated the early Stuart sockeye stock, the first run every year, that spawn above the slide in July and August. Fisheries and Oceans Canada reported that 99 per cent of early Stuart didn’t make it past the landslide.

But Michielsens said “the tragedy is that the returns had been so low already” before Big Bar.

Only 493,000 sockeye returned in 2019 when 4.8 million had been forecast.

“Big bar slide was a complication on top of that,” Wimbush said. “Fraser River people [north] of Lillooet are definitely in dire straits in regards to all their salmon stocks.”

Wimbush said there should be a ten-year hold on harvesting, if that’s what it takes to save sockeye.

“The decisions we make today will affect our children in 150 years because the decisions made 150 years ago are affecting us today.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

The Alberta premier’s separation rhetoric has been driven by the oil- and secession- focused Free...

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...