Family farmers in British Columbia were already struggling. Then Trump started a trade war

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

The landscape is the stuff of legend.

Lush boreal woods, pristine lakes and roaring rivers blend into steaming, soggy muskeg and merge with the sparse, icy tundra of Manitoba’s Arctic coast.

It’s described as an untouched wilderness — Travel Manitoba calls it “mostly still wild” — but flying toward the northern Manitoba industry town of Gillam, there’s a crack in the mirage: an unnatural, linear scar across the snaking rivers and undulating woods.

More than 70 per cent of the province’s electric power travels on the Manitoba Hydro Bipole transmission lines, a high-voltage highway that links a series of northern dams to urban neighbourhoods across the south.

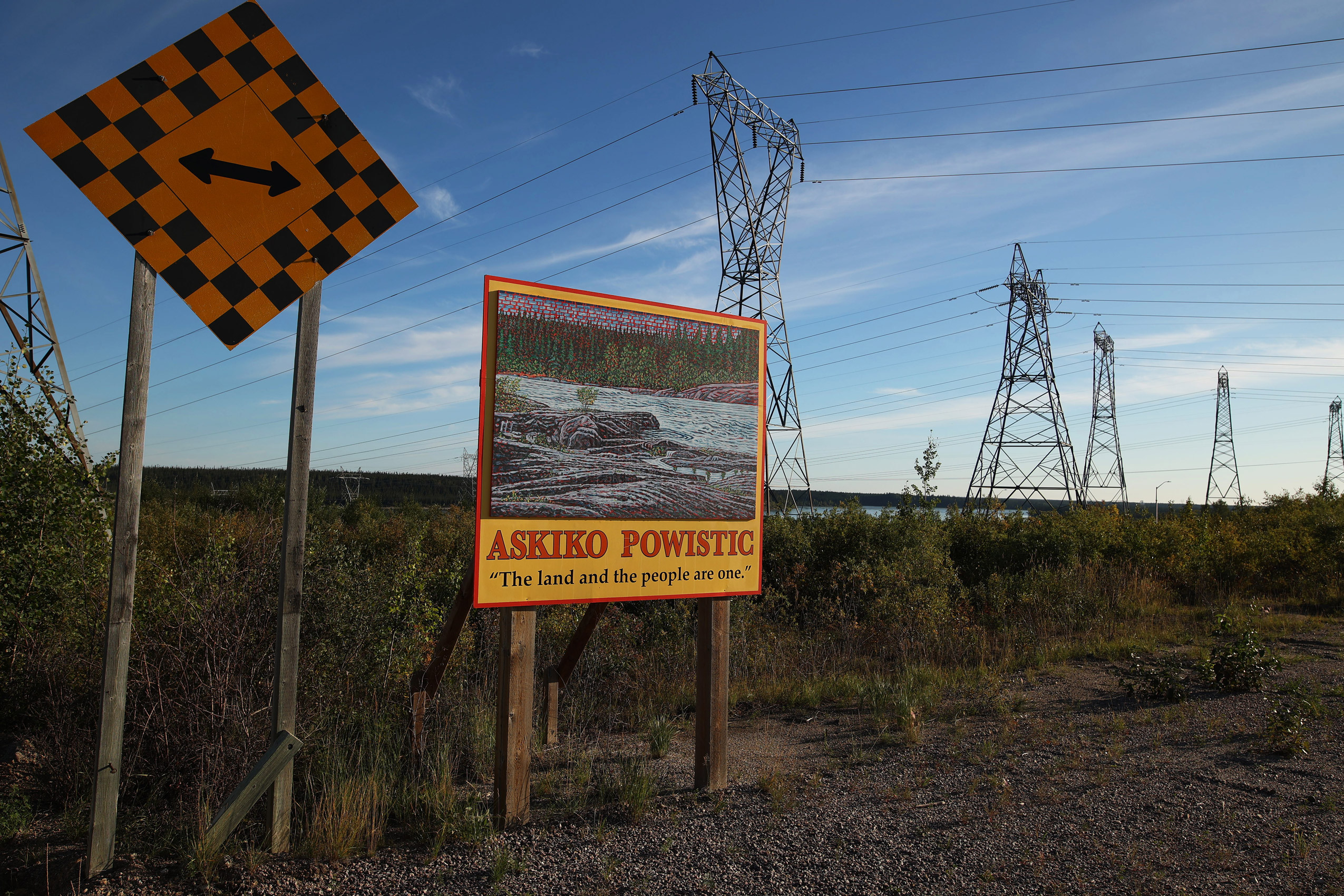

From the ground, its presence is all the more imposing. While powerlines can feel at home in urban centres, where they’re strung along tree-sized posts next to busy roads or through back alleys, in the midst of the boreal forest, power infrastructure is more looming than familiar.

Steel transmission towers stand some 40 metres — taller than two city buses stacked end to end — in a clearing as wide as 50 highway lanes. The towers dominate the skyline, connected by a dizzying web of power cables that dangle above the wild tangle of wetlands and woods.

Hydroelectric generation — the source of more than 95 per cent of Manitoba’s power — is celebrated as low-emission and low-impact energy. While its emissions profile is comparatively low, in northern Manitoba, its impacts on the landscape and the people who live here are impossible to ignore.

The Narwhal and Free Press visited the area around Gillam in September to attend the launch of a protected area proposal by the York Factory, Fox Lake, Tataskweyak, War Lake and Shamattawa First Nations. All five communities have felt the impacts of Manitoba Hydro’s developments on the land, the people and the rivers.

Daily trips to Fox Lake’s culture camp on the banks of the Nelson River offered an up-close look at the heart of Manitoba’s power supply.

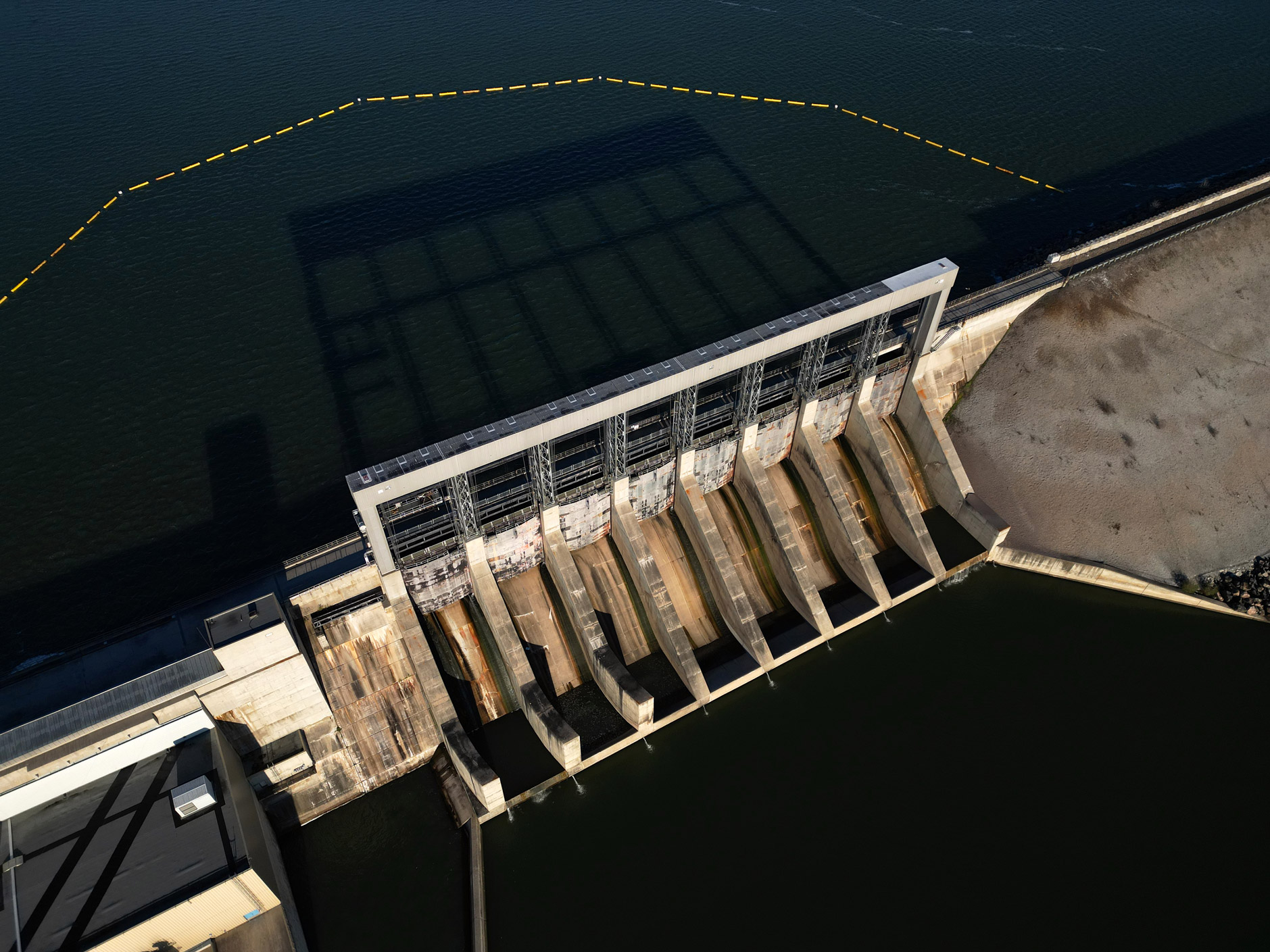

Provincial Road 280, the half-gravel, half-paved highway that connects a string of northern towns, crosses the river on the Long Spruce Generating Station.

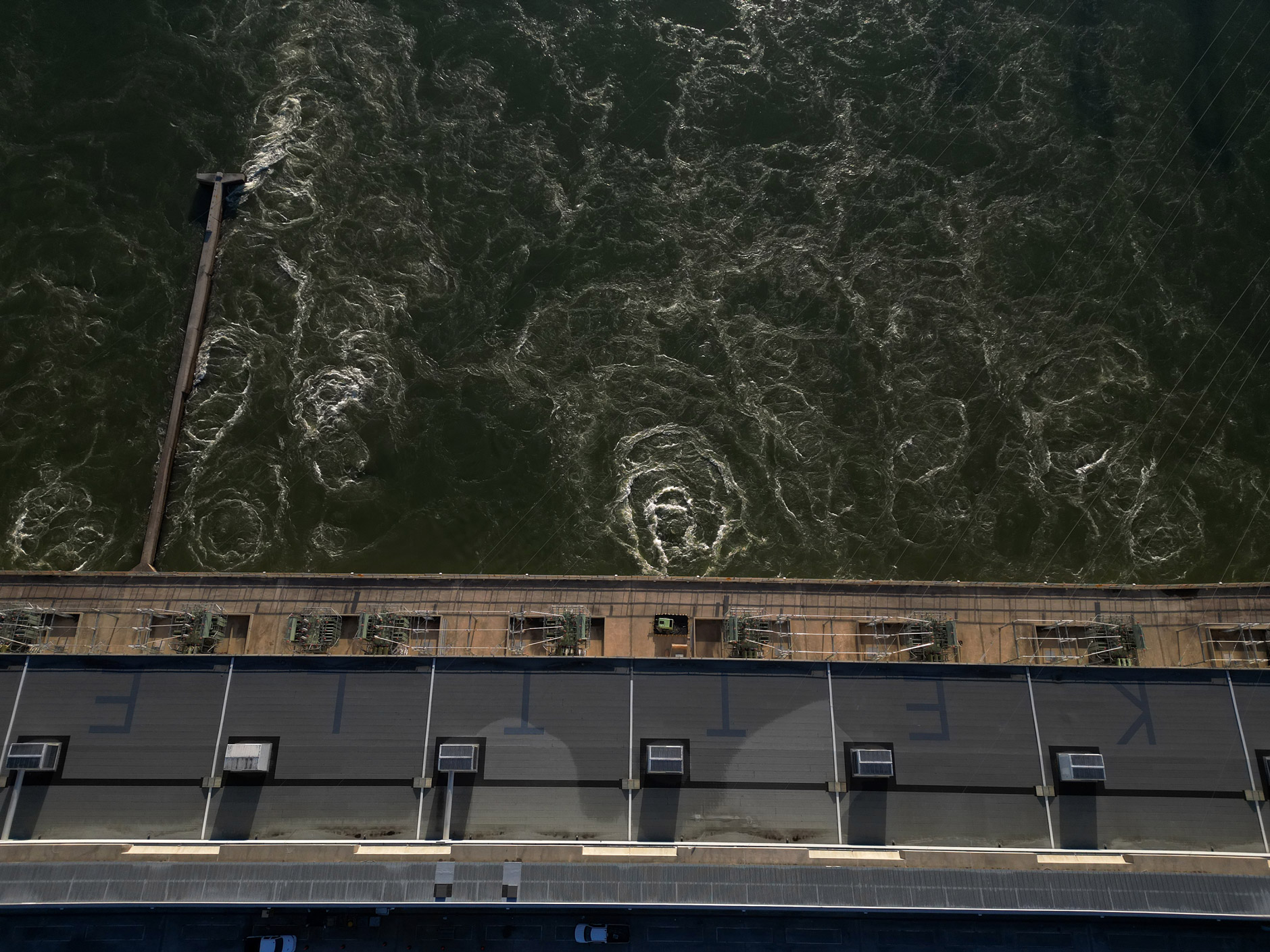

To one side, the placid forebay waters lap at the edge of the roadway. On the other, past the long concrete powerhouse and towering spillway gates, the ground drops away. Down a 26-metre slope, the river reappears in a row of churning whirlpools, byproducts of the largely hidden mechanics that turn the river’s flow into electricity.

Through a series of lakes, rapids and falls, the Nelson River, called Kischi Seepee in Cree, descends more than 200 metres on its nearly 650-kilometre path from Playgreen Lake, near Lake Winnipeg, to Hudson Bay.

For generations, its waters served as a vital transportation link for northern Cree (or Inninew) communities, who paddled between home settlements, hunting and trapping grounds across the northern coast. Its abundance of fish served as a source of both sustenance and economic opportunity. Its clear, pea-green current served as a constant source of drinking water.

But Manitoba’s power planners had been eyeing the Nelson as a source of power since the early 20th century. The elevation changes — that once gave the river a reputation for challenging navigation — appealed to engineers who estimated the power of its roaring rapids could be worth more than $1 million per day if electricity cost just one cent per kilowatt-hour.

Many of Manitoba’s dams are considered “run of river,” meaning they rely on natural flow rates to generate power. The mechanism is fairly simple: water in the forebay (upstream of the dam) flows into the powerhouse through intake gates, which funnel the water down a steep drop into a row of scroll cases — spiral-shaped rooms — that each house a massive turbine.

The shape of the scroll case forces the water into a swirling movement that spins the turbine, which in turn spins a large electromagnet to generate a current. The water bubbles back out to the river and continues downstream, while the current is sent along a network of transmission lines. Fish — including the iconic lake sturgeon — are unable to swim upstream past the dams, meaning they can’t travel the length of the river.

Manitoba built its first hydroelectric dam on the Little Saskatchewan river near Brandon in 1900. By 1955, it had tapped all the available hydroelectric power on the Winnipeg River with six dams. Another was built at Grand Rapids on the more northerly Saskatchewan River in the late 1960s.

But the Nelson was, as described in a 1990 Winnipeg Free Press article, “a modern El Dorado — the last great hydroelectric resource on the continent.” Hydro estimated its hydroelectric potential was about 14 times greater than that of the Winnipeg River.

Not only could its naturally powerful flow generate enough electricity to meet rapidly growing demand in southern Manitoba, it was sure to provide enough surplus to make Manitoba Hydro a major player in the North American energy export market.

“ln a world belatedly becoming aware that fuels such as oil, coal and natural gas will one day be completely gone, the value of water power is appreciated more and more,” the utility wrote in a 1975 informational pamphlet.

“When the last ounce of mineral wealth is wrested from the ground, our water resources will be intact and worth more than ever.”

One dam — Kelsey — had already been built on the Nelson, just upstream of Split Lake, to power a nickel mining operation and burgeoning company town in Thompson.

Any further development on the Nelson had been stalled by one major obstacle: it was too complicated and costly to transport power over hundreds of kilometres of rugged terrain to reach the population hubs in the south.

In the 1960s, Manitoba Hydro, then a newly created Crown utility, developed new transmission technologies that would make it feasible to dam “the mighty Nelson.”

Each dam brought permanent overland flooding that destroyed hunting, trapping and fishing grounds for the First Nations along the Nelson’s shores, and altered river ecosystems.

“That water that you see held back behind the Hydro dams, that’s not the liquid that we drink, that’s fuel for their generators,” Robert Spence, an environmental monitor and former councillor from Tataskweyak Cree Nation, says in an interview.

“The rivers are no longer the rivers that we once knew them as — they’re extension cords.”

To control water levels on the Nelson River, especially in the fall and winter when natural flows are lowest and Manitoba’s power demand is at its peak, the utility built dams and diversion channels where the river flows out of Lake Winnipeg, turning the lake into a massive reservoir for its power stations.

Along with the dams, Manitoba Hydro built two parallel powerlines capable of carrying high-voltage power. These Bipole lines transect approximately 900 kilometres of boreal forest and interlake wetlands from conversion stations near Gillam to another just north of Winnipeg. In all, Manitoba Hydro cleared an area about a quarter of the size of Winnipeg for the Bipole lines.

Hydro saw potential to generate more power — and more export revenues — by re-drawing the natural pathways the water had carved through the northern bedrock over many millennia.

In the early 1970s, the Crown utility opted to exploit the hydroelectric potential of the Churchill River, which runs parallel to the Nelson, by holding back its flow in Southern Indian Lake and blasting a new channel from the lake into the Nelson river system.

The impacts were monumental.

Though it increased generating capacity on the Nelson by 40 per cent, raising the level of Southern Indian Lake created significant flooding, O-Pipon-Na-Piwin Cree Nation was forced to relocate from their home along the lakeshore, and still navigates unpredictable water levels as a result of the diversion to this day.

Tataskweyak Cree Nation, on the shores of Split Lake, suffered the decimation of their water quality as silt and mercury levels increased. Tataskweyak has operated under a boil water advisory since 2017.

The diversion destroyed commercial fisheries, decimated the once-abundant Churchill River sturgeon population, changed animal migration patterns and hamstrung local Cree economies and cultural practices. Sturgeon numbers — a critical food and economic resource — plummeted. Spence says there is just one sturgeon population left on the lower Churchill River.

“They killed off whole populations. It affected all the fish, it affected how animals moved through the area,” he says.

In the 1975 information booklet, Manitoba Hydro predicted the diversion would change fish and animal habitat and force some homes and businesses to relocate, but calculated “that the net resource gain far outweighs all other considerations.”

“Certainly the greatest impact upon residents of the affected areas will be the end of their isolation,” Manitoba Hydro posited.

For its part, Manitoba Hydro says it is working toward addressing its legacy. “We acknowledge the impacts of our projects and operations, and have entered into a range of agreements with Indigenous communities and organizations to address those impacts,” Peter Chura, a spokesperson for Manitoba Hydro, said in an emailed statement. “We are continuing to work collaboratively to address adverse impacts and to strengthen and improve our relationship with Indigenous communities.”

Years after the Churchill diversion, the province and the Crown utility recognized the devastating impacts of the project on First Nations and signed an agreement to compensate communities for the damage. Actual implementation of the agreement was tied up in courts for several decades; First Nations would not see any compensation until the 1990s. The settlements would total more than $400 million by 2000.

Development on the Nelson carried on.

Manitoba Hydro struck an export deal with a U.S. power company in the 1980s, allowing for the development of the Limestone dam — Manitoba’s largest generating station.

In the years since, the utility has ramped up its export contracts to the United States, Ontario and Saskatchewan. The latest hydroelectric generating station in the province, Keeyask, was built on Stephen’s Lake in the Nelson River system between 2014 and 2022 to fuel further power exports.

Power sales made up a quarter of Manitoba Hydro’s electricity revenue over the last 10 years, totalling nearly $6 billion.

But the looming electrification of heating and transportation is expected to increase local demand on the Manitoba Hydro grid, according to the utility’s 2023 Integrated Resource Plan, and in turn prompt a drop in extraprovincial power sales.

“Manitoba Hydro’s energy and capacity resources are limited. We already anticipate not renewing some of our current contracts for exports of electricity as that surplus energy will be increasingly required to meet your needs here in Manitoba,” then president and CEO Jay Grewal wrote in the introduction to the report.

Regardless of the need for more power, there are no immediate plans to build another dam.

In the meantime, the string of dams along the Nelson River have already left their mark on the land, water, wildlife and the people who live along its banks.

“All those dams have had a major impact,” Spence says. “Not just environmental, but social impacts as well. We’re still reeling from the effects of those dams.”

Julia-Simone Rutgers is a reporter covering environmental issues in Manitoba. Her position is part of a partnership between The Narwhal and the Winnipeg Free Press.