Drawing (on) a decade of climate change in the North

Artist Alison McCreesh’s latest book documents her travels around the Arctic during her 20s. In...

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

It’s Tuesday night in a community centre at the heart of Manitoba’s Interlake region — a patchwork of forest, wetland and prairie grassland just 90 minutes north of Winnipeg. Nearly 200 people have packed into the building for a conversation that many believe could forever change their relationship to the community and its lush, wild landscapes.

They’re decked out in Carhartt overalls, camo hats and reflective jackets. Many are neighbours and friends who gather in clusters to catch up as they prepare to take their seats. A sense of anticipation hangs over the room.

Asked why he’s chosen to come out to the Arborg-Bifrost Community Centre, Lyndon Dueck, an agricultural worker and resident of the 1,300-person town, says he’s concerned about the federal government “regulating how we can use the land.”

“This is a farming community and that definitely concerns us,” he says in an interview. “They’re trying to create a divide between us farmers, and people that live here, and the First Nations.”

They, in this case, refers to both the federal government and the Manitoba chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, the conservation-focused non-profit that helped organize the evening’s event in partnership with the chiefs from three Interlake First Nations: Peguis, Fisher River and Kinonjeoshtegon.

The meeting in Arborg was first announced several weeks prior as part of a series of town halls and information sessions to gather feedback for an Indigenous-led conservation area proposal in the Fisher Bay region. Past community engagement sessions had a couple dozen attendees but this one, like a similar meeting held in nearby Riverton a month earlier, looks set to be tense.

Nearly every seat is occupied; there are a handful of uniformed police officers leaning against the wall near the door, keeping an eye on the event. The crowd is a mix of landowners, farmers, peat mine workers, Indigenous leaders, cottagers, hunters and politicians. Most are there because they feel there are questions about the protected area proposal that have not been answered, questions they worry are being ignored to allow outsiders — be it the federal government, the Parks and Wilderness Society or, for some, even the United Nations — to stake control over the surrounding land.

Midway through the evening, during a question-and-answer segment intended to quell some of these concerns, Dueck finds himself in an exchange with Peguis First Nation member Keith Flett.

Flett has been at the microphone for a few minutes, defending his nation’s right to guide decisions about how the land is stewarded and telling stories about his time living on land: taking children out to hunt, swimming in the river, working as an engineering technician assessing mining and industrial projects in the region.

“I heard the comment you made about taking your land,” Flett said, facing the crowd and explaining the treaties that cover central Manitoba. “A lot of our land was freely given. Before you start making comments, learn the history.”

Dueck chimes in from his seat: “What I’m scared of is that First Nations people have been screwed over by the federal government over and over. Do you trust the federal government?”

It only takes a few minutes of conversation for Dueck and Flett to acknowledge they are, for the most part, on the same page. They both want a voice in decisions that could affect the communities they were raised in, that they work in and raise their families in. They have both felt ignored by government officials that aren’t connected to the region.

As Flett leaves the microphone, he pauses at Dueck’s seat, and the two share a hug.

For many, that conversation — that hug — reflects the only real solution to a knot of controversy around the future of conservation in Manitoba.

The Interlake protected area is the latest battleground for the “Access for All” campaign, spearheaded by the Manitoba Wildlife Federation, which has opposed Indigenous-led protected areas as well as federal and provincial conservation targets in response to concerns these areas will restrict access for hunters, anglers and landowners.

The campaign has sparked questions about how protected areas are developed, who is in charge of decision-making and what implications and restrictions they might hold.

The debate has been messy; there are real fears, long-standing grudges, legal quagmires and broad political messages at play. It’s been hashed out in a volley of opinion articles in local newspapers, in town hall meetings and on social media.

But many people lending their voices to the chorus, like Flett and Dueck, ultimately have a shared vision: they cherish Manitoba’s wilderness — its fishing holes, abundant wildlife and rugged land — and want to preserve these riches for their children and grandchildren.

And many agree, as Dueck says in an interview after the Arborg meeting: “It has to be conserved by local people.”

A little over a year ago, the Manitoba Wildlife Federation publicly supported Indigenous-led conservation. In an opinion article in the Free Press, senior policy advisor Chris Heald expressed support for the Seal River Watershed Alliance’s proposal to conserve about 50,000 square kilometres of northern Manitoba. His sole caveat was that the proposal honour the interests of the 14,000 licensed hunters, anglers and conservationists the federation represents.

“The [Manitoba Wildlife Federation] supports actions that protect our public lands from industrial development and promote sustainable use and enjoyment of our fish, wildlife and outdoor resources,” Heald wrote in March 2024.

The federation is itself a conservation group, and receives provincial funding for fish and wildlife protection programs, wildlife management area land management projects and private land conservation.

But when the Access for All campaign launched in January, the federation’s tone had changed. A post on the organization’s website described Indigenous-led conservation areas as initiatives that “threaten to alienate the public from these shared resources and undermine long-standing traditions and livelihoods.”

“In Manitoba, [Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas] are being promoted as a key tool to meet the 30×30 goal,” the post continued, referring to international targets to conserve 30 per cent of lands and waters by 2030.

“These areas often involve agreements between Indigenous communities and government entities to designate large tracts of Crown Land as protected, barring certain activities like resource extraction (mining, forestry, and other industry sectors) or non-Indigenous hunting. The [Manitoba Wildlife Federation] is investigating legal options for stopping the [Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area] development due to the lack of public consultation.”

So why the change of heart?

According to Dennis Schindler, the Manitoba Wildlife Federation’s senior land conservation specialist, the organization’s tone “comes from not being heard by the province and federal government.”

“With respect to 30 by 30, our issue is it’s a global initiative, and we support local solutions to local problem-solving and local management,” Schindler says in an interview.

The global 30-by-30 target is one of 23 targets included in what’s called the biodiversity plan — an agreement ratified by 190 countries at the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity in 2022 aimed at stopping and reversing global biodiversity loss. Because habitat loss is a leading cause of species loss, protecting habitat through conservation is seen as a way to restore biodiversity. Canada, and later Manitoba, adopted a 30-by-30 target as policy. Biodiversity treaties and targets have been in place since the early 1990s.

As Schindler explains it, the federation worries hunters, cottagers and other land users will be left out of decision-making processes and will eventually be pushed off of the land they live, work and play on as protected areas are developed and land use restrictions are put in place to align with targets established in Ottawa or at the United Nations, rather than in consultation with the community.

“We’re very insistent in our discussions at the local level that we need complete transparency and we need the province leading this, because the province has a responsibility to engage all Manitobans in this discussion,” Schindler says.

“When you ask the questions that people are asking at these meetings and there’s no answer, that’s because the province is the only one that can answer. So people get frustrated, people develop a lack of trust.”

A few hours west of Arborg, in the rolling hills and bur oak forests of the Little Saskatchewan River valley, distrust of the federal government — especially Parks Canada — runs deep.

Riding Mountain, Manitoba’s southernmost national park, has a history mired in controversy. Its establishment forcibly expelled members of the Keeseekoowenin Ojibway Nation; it faced years of opposition from western Manitoba farmers and loggers.

According to Schindler, the still-strained relationship can help explain why a federally supported proposal to develop an ecological corridor linking the park to the Assiniboine River was shot down.

“Parks Canada has attempted to influence land management in the area around that part of the park for decades,” Schindler says. “But how the issue amplified was the lack of communication at the local level and the lack of answering questions.”

In late November, the federal government announced it would grant the Assiniboine West Watershed District, a land management board made up of community representatives, nearly $1 million to develop a plan to support research, land management and conservation strategies along the Little Saskatchewan River. The program would be led by the watershed district, with support from local universities and involve collaboration with landowners and First Nations, who could opt in to the program.

But by mid-January, the project was dead in the water. A one-sentence press release from the watershed district board said the project was declined “due to extreme opposition.”

The wildlife federation celebrated it as a win. Others, like former Liberal MLA Jon Gerrard, lamented “inaccuracies” from the federation that linked the project to Indigenous-led conservation and 30-by-30 targets (ecological corridors are complementary to conservation areas, but are not considered protected areas), and stoked fear the project would impact private property rights.

An article Schindler wrote on Jan. 14, a day before the wildlife federation held a town hall meeting to discuss the corridor project, suggested “the impact on private land use, municipal sovereignty over decision-making, and the imposition of national park management over large parts of our province should be a concern for all Manitobans.”

Schindler says the federation later tried to correct “a rumour” the project would involve taking away private property.

He says residents already didn’t trust Parks Canada’s involvement and had questions about how the program would impact farmers, hunters and other land users. Parks Canada’s documents felt “prescriptive,” he says, and they worried it would come with hidden restrictions and get in the way of existing agricultural conservation strategies like grazing.

Residents felt their concerns were being dismissed at the local level, amplifying division and tension in the region until the corridor fell apart.

Schindler says “it’s a shame that there’s so much divisiveness there now” and acknowledges better communication from all parties is needed to “ensure these things don’t happen again.”

He admits the federation’s “blunt” communication could have played a role, but stresses the hunters, anglers and land users the federation represents ultimately just “want to be heard.”

It’s the same set of concerns now facing the Fisher River conservation area, the Seal River Watershed and other proposed Indigenous-led conservation projects: the federal government — and anyone working on its behalf or with its funds — should not be trusted to make decisions about local land use without the input of people on the ground.

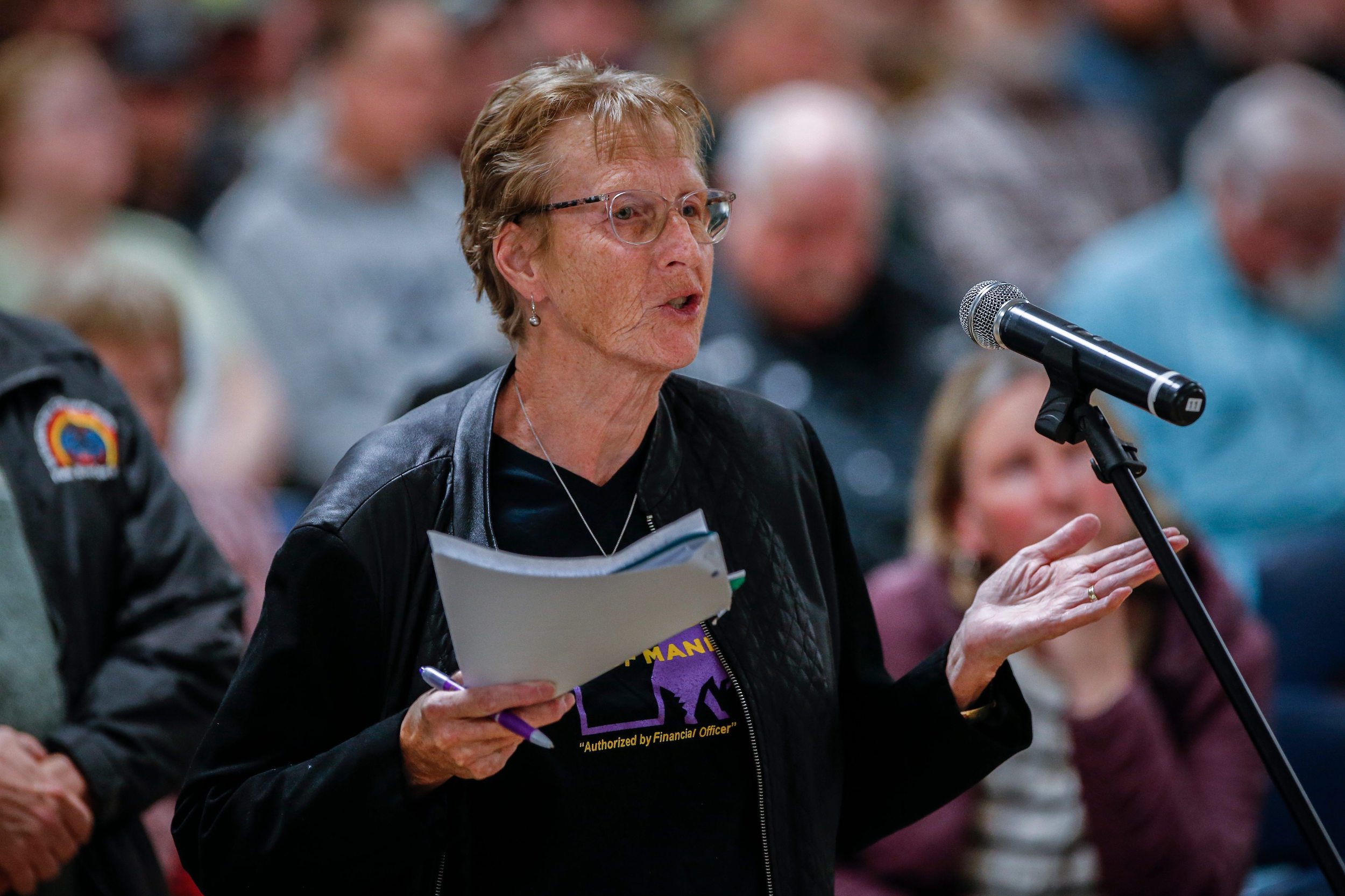

“We have to talk to one another. We have to know what each other’s goals are. We still don’t know what the goal is here,” Deb Mason, a west Interlake resident, said in an interview at the Arborg town hall.

“When you’ve got the federal government and the [United Nations] involved, the gloves are off. There’s no trust.”

For Mason, and many others in attendance, the project is a manifestation of international conservation targets that were established — and adopted as both federal and provincial policy — without local input. They see the goal of protecting 30 per cent of the world’s lands and waters by 2030, as a way to wrest control of the land away from those who live on it and bar access for most activities. In the case of the Fisher River conservation area, there are concerns about the involvement of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness society, which has long supported conservation targets including the 30-by-30 initiatives and provides organizational support to the three First Nations who lead the initiative; in the case of the Seal River watershed, the wildlife federation has concerns about the role Parks Canada will play in establishing a protected area.

The Parks and Wilderness Society, which has found itself in the wildlife federation’s crosshairs through the campaign, says it has not called for restrictions to hunting and angling in any protected area it has supported through its 34-year history and is not advocating for private property or leased lands to be included in conservation efforts. In a statement, Ron Thiessen, executive director of the society’s Manitoba chapter, says the organization was surprised by the wildlife federation’s claim that the protected area would erode access to public lands.

“This misinformation led to many people walking into the meeting with inaccurate information and they were justifiably concerned,” Thiessen says, referring to the meeting held in Riverton in February.

Thiessen says the parks and wilderness society supports Indigenous-led conservation “as part of our commitment to reconciliation and environmental protection,” and notes 30-by-30 targets are about “responsible land management — balancing conservation with economic opportunities like forestry, and other resource development in a way that keeps 30 per cent of the land base as undeveloped natural areas.”

During the Q&A portion of the event in Arborg, Mason asked the three chiefs whether they would commit to hosting roundtable discussions with the communities to decide on a path forward for the protected area.

“The only way we’re going to get to the bottom of this, in my opinion, is to have some roundtables where we discuss it, we complain about it, we come up with some resolutions for it, some solutions for it, some trust — and who knows, you may find out we’re all great partners together,” she said, garnering applause from the crowd.

Fisher River Chief David Crate agreed.

“Sitting down across from each other, you get to know the individual’s interests, their concerns, how we can work together and that’s exactly what we want to do,” he responded.

To Mason, roundtable discussions are an antidote to the “mistrust and misinformation” that’s characterized the conservation debates across Manitoba.

“I sincerely hope that we’ll get a better understanding of each other,” she says after the meeting. “Who knows, we may have a lot of goals in common, it’s just right now we’re not expressing them properly.”

The sentiment rings true in northern Manitoba’s Seal River watershed, where an alliance of four First Nations have spent the last five years developing a proposal to protect the province’s last undammed river and the vast, ecologically rich watershed it supports.

Stephanie Thorassie, executive director of the watershed alliance, acknowledges a busy year both personally and professionally interrupted some of her efforts to reach out to stakeholder groups, but in recent months she’s been able to meet with lodges, hunters and others with concerns about the proposal.

“The conversations have been really positive, and left me with hope in working together to find ways to ensure that people’s concerns have been heard,” she says in an interview.

The Seal River is among the largest Indigenous-led protected areas currently under development in Canada, and the first ever in Manitoba.

Years of consultation with nearby communities like Thompson, Churchill and the four nations within the watershed have helped guide the proposal thus far, as have ongoing discussions with the federal and provincial governments, mining and prospecting businesses, lodge owners and environmental non-profits. The alliance recently finished a feasibility study — prepared in partnership with both Crown governments — and will enter another round of consultations and community engagement as it nails down the details of the proposal. Final decisions about land use — including whether a national or provincial park may be included in the protected area — will be made by the province after it conducts its own consultation and engagement processes.

Indigenous-led protected and conserved areas, or IPCAs, refer to any type of protected area where the “purpose, development, establishment and ongoing management” are led by Indigenous communities. There is no formal legal definition of an IPCA, in part because each is unique to the area it’s in and the communities managing it. The protected area can include a patchwork of conservation tools, such as parks, ecological reserves or wildlife management areas, while the management structure can include a variety of partners, such as Crown governments, land trusts and non-profit organizations.

“A lot of people seem to think that we’re further along than we are and decisions have been made and that we’re excluding people. I really think there’s a lot of fear and misinformation out there that’s causing people to feel this way, and it’s really just touching base with everybody again, reminding them where we are in the process and letting them know that we’re bringing them in to do this work with us — beside us,” Thorassie says.

“There’s misinformation out there that we’re trying to keep people out, which has never been the case. We know that we can’t do this work in siloes and we definitely don’t want to be keeping people out of the north. It’s actually the opposite: we’re trying to encourage tourism, encourage people visiting and sharing our unique culture with us.”

Thorassie has been confused by the campaign against the protected area, though she understands that Indigenous-led conservation is an unfamiliar decision-making process.

“This is a new way of working and it’s allowing ourselves the opportunity to be at the table and have a say. We’ve never had that opportunity before and it’s the reason why my community was relocated and a third of my people died as a result,” she says, referring to her Sayisi Dene community. “These things have not worked for us in the past. Now is the time to move forward and make changes that see positive results for community members, for Manitobans and Canadians.”

It’s an echo of the voices in Arborg’s town hall, who worry the decisions made by faraway policy makers will damage their way of life. Thorassie says that’s a reality her people have experienced — and not a status quo the four nations are keen to uphold. Parks Canada and the provincial government are, in this case, taking cues from the alliance, not the other way around.

“Change can be scary for some people, and we’re doing this very new thing in the province and we are looking to make some change to a fair size of land, but really we have the intentions and the hope of doing this not only for the communities but for our province,” she says. “It’s something to be proud of. There aren’t a lot of spaces in the world that are like this.”

It’s ultimately this grassroots co-operation Schindler says the wildlife federation is advocating for, too.

“We want to work with local communities — Indigenous and non-Indigenous — with our expertise in developing conservation-related projects and programming that benefit all people that live within that area, not to meet a United Nations goal of protecting 30 per cent by 2030,” Schindler says.

Whether Canada continues to pursue 30-by-30 targets or support Indigenous-led conservation is murky. A change in government could upend Canada’s current conservation strategy.

The debates heard around Manitoba have already been posed at the federal level; the wildlife federation was invited to speak to the federal environment committee in December, where it reiterated its opposition to national conservation targets.

In an opinion article published following the demise of the ecological corridor, the wildlife federation’s Rob Olson wrote: “Federal winds of change are blowing. Regardless of who is running the country next, we all have an opportunity for a new national conservation strategy that brings us all together instead of dividing us.”

Schindler says the federation is currently working on a policy paper outlining its vision for effective conservation in Manitoba, which he hopes will be ready in time for the organization’s annual general meeting this month.

That vision will prioritize “shared management, regional solutions” and a blend of traditional and science-based approaches to conservation, he says.

“In general terms, what we’re talking about is … people working together to solve problems within their communities, within their watersheds.”

It’s in essence the same vision held by Indigenous communities leading conservation projects. Taylor Galvin, an environmental scientist and member of Brokenhead Ojibway Nation, says the grassroots approach is what sets Indigenous-led conservation apart from traditional land protection projects.

“It’s not just quantitative data, it’s qualitative, observational, real-time data. We’re the ones who live with the impacts, we’re the ones who see it day by day, how the world, how the landscape changes on a day-to-day basis,” she says,

“What western science is missing is that spiritual connection to the land; that’s what’s guided us for so long and that’s what we’re bringing to the table today.”

In Arborg, it’s a path forward that gives Dueck, the agriculture worker, hope too. Effective conservation, he says, needs to balance the environment and the economy, and ultimately needs to be led by those who use the land day in and day out.

“It has to be a real conversation, like we saw here tonight, on what we can do. It has to be [rural municipalities] working together. It has to be people, farmers, First Nations working together,” Dueck says. “The people that actually work the land, they know what they’re doing. It’s not the government. They don’t know.”

Julia-Simone Rutgers is a reporter covering environmental issues in Manitoba. Her position is part of a partnership between The Narwhal and the Winnipeg Free Press.

Updated April 7, 2025, at 11:34 a.m. CT: This story has been updated to clarify that it is specifically the Manitoba chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society that helped organized the event in Arborg, Man.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

Artist Alison McCreesh’s latest book documents her travels around the Arctic during her 20s. In...

I’ve watched The Narwhal doggedly report on all the issues that feel even more acutely...

Establishing the Robinson Treaties, covering land around Lake Huron and Lake Superior, created a mess...