The Narwhal’s in-depth environmental reporting earns 11 national award nominations

From disappearing ice roads to reappearing buffalo, our stories explained the wonder and challenges of...

When Sio Silica announced its plan to become a publicly traded company in November — just weeks after Manitoba had elected a new government — the out-of-province sand miners expressed confidence they were on the verge of breaking ground.

“Permitting underway — process well defined and understood, extraction permit expected in Q4 2023,” the Alberta-based company told investors in a presentation. “No federal permit required. Provincial government supportive of critical mineral processing.”

Such confidence would come as a surprise to some residents of the small agricultural communities just a stone’s throw from Winnipeg, where Sio Silica has announced plans to drill thousands of holes through two aquifers over the next two decades for what it claims will be “the greenest sand mine in the world.”

As far as these communities were aware, Manitoba’s Environment Department was still poring over the company’s hotly contested application for an environmental licence — and a decision wasn’t coming any time soon.

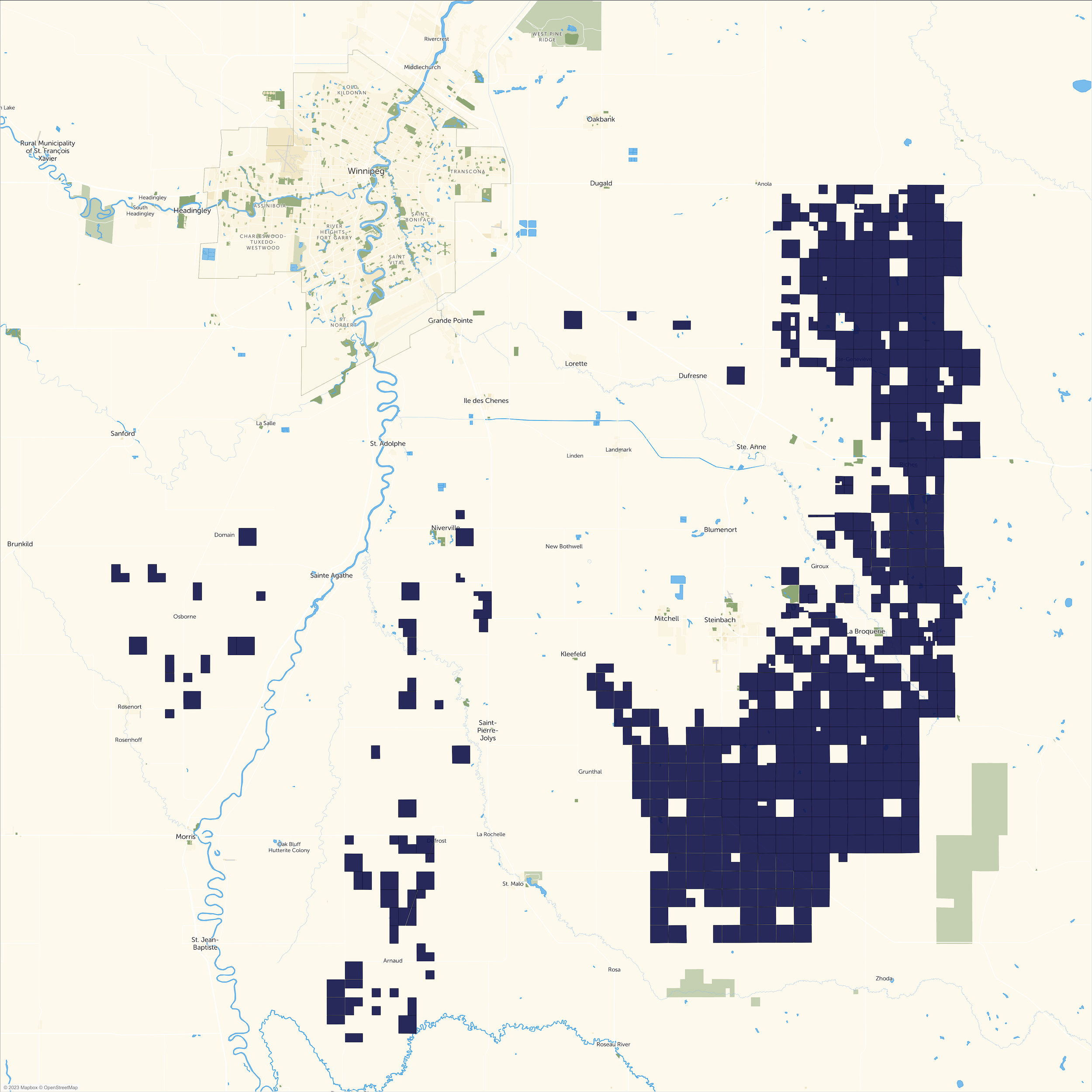

Sio Silica was founded in 2016 (it was called CanWhite Sands at the time) as a junior mining company on the hunt for silica sand in Western Canada. The company laid roots in Manitoba the following year after finding a large, silica-rich sandbar in the rural municipality of Springfield, less than 50 kilometres outside Winnipeg.

In touting its proposal, the company says it’s poised to help Manitoba become a leader in the green economy. It also says it has found what it believes is an unparalleled source of high-purity silica sand, used to make in-demand technologies like solar panels and lithium-ion batteries, and it plans to airlift more than 1.3 million tonnes of it out every year through hundreds (eventually thousands) of 60-metre wells across 850 square kilometres of mineral claims. The company says its operations, which include a processing facility to refine the sand and ship it to market by rail, will create between 50 and 100 direct jobs and generate some $1.2 billion in revenues for the province.

But a number of Springfield residents have been unwavering in their opposition to the mine, concerned the airlift extraction will cause irreparable harm to the region’s drinking water aquifer.

“I think what Sio Silica offers is pipe dreams,” resident Gloria Romaniuk said. “They offer great risk.”

The fears of those residents were validated in June when an arms-length provincial advisory agency called the Clean Environment Commission released an independent review of the contentious environmental licence application. The commission said it had no previous knowledge of the airlift method of extraction used at this scale and concluded it “[did] not have sufficient confidence that the level of risk posed to an essential source of drinking water for the region has been adequately defined” and recommended the province get a lot more information before moving ahead.

As far as the public knew, Manitoba was still gathering that information when Sio Silica announced its imminent launch on the New York Stock Exchange. This deal has still not closed yet and it’s not clear when that would happen.

It would turn out a scandal was brewing behind closed doors in the legislature. Speaking with the Free Press in December, Premier Wab Kinew revealed the project was all but rubber-stamped by the time the New Democratic Party formed government. He later alleged a member of the former Progressive Conservative cabinet had tried to secure an approval during the transition period between governments.

Manitoba’s ethics commissioner is now investigating several Tories, including ousted premier Heather Stefanson, for potential violations of conflict of interest laws. The province has said it’s going to take more time to decide on the company’s licence application, but won’t take the investigation into account.

Controversy has bubbled around Sio Silica’s proposal for years.

Residents say the latest revelations only confirm their long-held belief Sio Silica has aligned itself with Manitoba’s political and financial power players to ensure their mine gets developed with or without public consent.

“It’s so easy for communities to be exploited by these pipe dreams,” Romaniuk said. “They’ve got all kinds of resources that the common citizen does not have — it’s really an unfair fight.”

As Sio Silica prepares to go public and more details of their political and financial web come to light, we’ve broken down those connections — and what they could mean for the licensing process.

Sio Silica has kept a tight lid on its list of investors, but the recent announcement the company would take its business public through a partnership with relatively unknown Pyrophyte Acquisitions Corporation has shed a sliver of light on the company’s books.

In its investor presentation, the company touts its partnerships with large investors, including a “strategic alliance with a large Canadian Pension Fund as one of Sio’s major shareholders” and a mining royalty company “wholly-owned by large Canadian pension fund.”

Previously, Sio Silica CEO Feisal Somji revealed in October 2022 that its largest shareholder was the Canadian National Railway Pension Fund.

The fund, also known as the CN Investment Division, owns several oil, gas and mineral royalty companies operating in Western Canada, one of which matches the royalty partner description outlined in Sio Silica’s investment deck.

Access to a railway is one of Sio Silica’s main selling points; the company’s website boasts that its processing facility “sits directly on CN’s main rail line.” According to documents released to the Free Press and The Narwhal through federal freedom of information legislation, Sio Silica has worked closely with CN to develop rail infrastructure associated with its processing plant.

Pyrophyte came on the scene in 2021, describing itself as a blank cheque acquisition company. It’s incorporated in the Cayman Islands, where it’s shielded from American tax laws, financed by a long list of American hedge funds and managed by a handful of long-time oil and gas executives.

“Pyrophyte’s sole function is to help a selected company in the process of being listed on a public stock exchange,” CEO Bernard Duroc-Danner said in an emailed statement.

“The selected company has to be in our industry of focus: supporting worldwide energy transition.”

Before Pyrophyte, Duroc-Danner spent three decades at the helm of several major oil and gas corporations.

One of those companies, Weatherford International, made headlines in 2013 after it reached a US $250-million settlement with several state and federal government departments for “apparent violations of U.S. sanctions in Iran, Sudan and Cuba,” according to the U.S. Treasury Department, and alleged violations of anti-bribery and trade laws.

In 2016, Weatherford paid the securities commission a further US $140-million to settle charges that it inflated its earnings through “deceptive income tax accounting,” according to the commission. The company did not accept or deny the allegations.

Duroc-Danner left the company two months later.

Somji faced his own financial investigations in 2019 while CEO of Prize Mining Corporation. Somji and other Prize Mining executives were named in an Alberta Securities Commission investigation into allegations the company misrepresented its financial position to investors and failed to follow disclosure rules.

Somji resigned less than a week after the securities commission publicly revealed it was investigating the matter. The company told the Free Press and The Narwhal there was no finding by the commission that he was involved in any wrongdoing.

The Alberta Securities Commission ordered the company to temporarily stop trading and disclose previously unreleased information. A spokesperson for the commission said the investigation has since concluded, but added they could not share further details. The Free Press and The Narwhal are not aware of any findings by the commission.

The company has maintained high-purity silica sand — a key component of green technologies such as solar panels and lithium-ion batteries — will be an increasingly in-demand mineral as the global electrification shift continues. The company believes its North American competitors are few and far between; there’s a sand mine in Rockwood, Mich., and another in Junction City, Ga., but those are expected to produce less than a million tonnes of sand per year combined.

Right now, most silica is mined in Asia and Australia. Demand is highest across Asia-Pacific countries, which manufacture semiconductors, lithium-ion batteries and other silica applications. According to the company’s market analysis, these countries are already exhausting existing supply.

“Sio well positioned to satisfy existing demand in China and [Asia-Pacific countries] with its low cost structure while North American demand grows,” the investor presentation reads.

Sio Silica has an “existing offtake agreement and [memorandum of understanding] with Chinese customers” — two semiconductor manufacturers — for the first 1.3 million tonnes of sand it produces. So far, Sio has no publicized agreements with Canadian or American customers, though the company said in an emailed statement it has “entered into non-binding memorandums of understandings/conditional agreements with organizations in Canada, the United States and the Pacific Rim.”

For example, Sio Silica has an agreement to sell its sand to RCT Solutions — a German solar panel manufacturer that’s proposing to build “North America’s largest solar panel plant,” in Manitoba.

“We believe partnerships such as this will create strong local demand for environmentally friendly, high purity silica,” a Sio Silica spokesperson said. “It is on this basis that we hope to see issuance of a licence as soon as is practical.”

Last summer, RCT Solutions signed a memorandum of understanding with the province to start exploring how to make the project a reality. Then-economic development minister Jeff Wharton — who is now being investigated by the ethics commissioner for allegedly trying to persuade former cabinet members to direct the Environment Department to approve Sio Silica’s mine — was the lead minister on the deal with RCT CEO Peter Fath. Wharton told the Free Press Manitoba would help with recruiting the company’s workforce, picking the plant site and applying for government funding.

For his part, Fath took the opportunity to put pressure on the province to ensure his company would be able to access local sand.

“What is missing, and what makes the case so strong for Manitoba, is access to the super pure quartz,” he told the Free Press.

His investors are keen and deep-pocketed, he noted, but “they won’t wait forever” for regulatory approval.

“Our preferred choice is Manitoba and I’m totally positive that the Manitoba government, which is so supportive, will find a way to clear this licensing issue,” Fath told the CBC in July.

While Wharton has been at the centre of the ethical complaints surrounding Sio Silica’s licence application, the allegations have also ensnared former premier Stefanson and her deputy premier Cliff Cullen. Former environment ministers Rochelle Squires and Kevin Klein have said they were both approached to approve the licence, but rebuffed the request.

(Manitoba’s Conservative caucus declined to offer comment on any allegations related to Stefanson or Wharton as the issue is before the ethics commissioner.)

“I have no conflicts,” Stefanson told the Free Press at an unrelated announcement last month. “That’s a fact. And I didn’t issue the licence during the caretaker time. Those are the facts.”

Wharton has previously said calls between cabinet members are confidential and that “no licence was issued; no convention was breached.”

Sio Silica’s relationship with Manitoba’s Conservative party, however, stretches back several years.

In 2020 and 2021, the company employed Marni Larkin as a spokesperson — a prominent conservative strategist who worked under former premier Gary Filmon and ran Stefanson’s widely criticized, ultimately unsuccessful 2023 re-election campaign.

Since its 2022 rebrand, Sio Silica has publicly appointed two names to its board of directors that have raised eyebrows with some Springfield residents.

“It’s like a little network, a club of people who are living a life that is different from the rest of us in the sense that, financially, they may be in a different circle than most people will know and they have influence,” Romaniuk said.

First was David Filmon, son of the former Conservative premier and corporate lawyer with a large western Canadian firm. Filmon has donated thousands of dollars to the provincial Conservative party since 2016, including a total $4,500 to Stefanson’s 2019 campaign and 2021 party leadership bid, according to Elections Manitoba filings.

“As a director of Sio I am aware that the licensing process has been ongoing for a long period of time (with significant back and forth) including with the prior government and now continuing with the current government,” Filmon said in an emailed statement.

“I support that process as I believe the project is poised to bring incredible economic opportunities and jobs to the province, while assisting the world in reducing its carbon footprint.”

While he supports the licensing process, Filmon said he has not participated in it.

The following summer, Sio Silica strengthened ties with the provincial Tories by appointing Mike Pyle, who it describes as “a well-known businessman and entrepreneur,” as a board member and chair of the company’s audit committee.

Pyle is CEO of Exchange Income Corporation, an aviation-focused investment company. He also chairs the Business Council of Manitoba, the Manitoba First venture capital fund and the Winnipeg Blue Bomber Football Club (Sio Silica was announced as a sponsor for the Blue Bomber training camp last May). He’s also donated more than $13,000 in total to the provincial Conservatives and Heather Stefanson’s campaigns since 2016.

In an emailed statement, Pyle said he has not participated in conversations between Sio Silica and the government, nor is there any business connection between Sio Silica and the Exchange Income Corporation. He joined the board, he said, because he was “impressed by the mine’s potential direct and indirect economic impact on Manitoba if the project proceeded.”

“The silica deposit is a world-class natural resource, and combined with Manitoba’s low-cost green hydroelectric power, it has the potential to be transformative to Manitoba’s economy and make us a world leader in green products such as solar panels,” he said.

According to Shiu-Yik Au, assistant professor of finance at the University of Manitoba, these political connections “stink a little bit” — but that doesn’t necessarily make them unethical.

“If you’re a business and you’re going into an area where there’s governmental involvement, you want experts who are connected to the various people in power,” Au said. “A lot of businesses are very highly dependent on political connections.”

As Au explained, the people with the best access to government are often the people in power themselves — or their friends and relatives. While it might be common practice in the business world, however, it can become unethical if conflicts aren’t transparently disclosed, and it tends to look unfair in the eyes of the public.

“It can be very, very frustrating to regular citizens that they don’t have access, but suddenly a company can come in … and get access to these super powerful people,” he said.

In a statement, a Sio Silica spokesperson said the company sought out “nearly 100 local individuals or companies from across the political spectrum that have business acumen and experience” to help it achieve its goals.

Some Springfield residents also said they were troubled by the role provincial Conservatives may have played in local leadership decisions.

The company had hired urban planners John Wintrup and Michelle Richard — a former Tory MLA candidate who has donated thousands to the party in recent years — as municipal planning consultants.

In June 2020, before submitting its environment licence proposals to the province, Sio Silica applied to Springfield’s municipal council for a zoning permit that would allow the company to build a processing facility in the region.

According to the municipality, the company abandoned its initial conditional zoning application after Springfield council asked for more information about the mine’s potential impact on the region’s aquifer. The company came back more than a year later with a more extensive zoning amendment that would rewrite some of Springfield’s bylaws to make room for the processing plant.

In the interim, the province was considering legislation that would give the municipal board — a quasi-judicial and provincially appointed body — power to resolve zoning and other land-use disputes between municipalities and developers. The bill raised red flags among municipal leaders, who worried it would allow the province to approve developments without the usual rigour of council meetings and public consultation — or overturn a council vote against a development. Decisions of the municipal board would be final; municipalities would not have the right to appeal.

Within the same period, from September 2020 to August 2021, Richard said she had recused herself from planning work and was serving as director of municipal relations for an advisory committee of Manitoba’s Finance Department.

Part of her job, she said in an interview, was to provide expertise and “act as an interlocutor between government and stakeholders” on municipal and planning-related government policy — including the controversial bill.

Sio Silica submitted its second zoning application in the spring of 2022, a number of months after the provincial legislation giving new powers to the municipal board had passed. So when Springfield council shot down the new zoning application in June 2022, the company was able to ask the municipal board to intervene.

Richard said she was not involved in developing the zoning applications Sio Silica submitted to council; that work was completed solely by Wintrup. However, Richard said she did assist with “necessary planning work” and “efforts to advance the site,” including community engagement, prior to taking a position in the provincial government. During municipal board hearings, Richard presented expert testimony on behalf of Sio Silica.

After three days of hearings and months of deliberation, the board handed down a decision in March 2023 ordering Springfield council to allow a less-extensive version of Sio Silica’s zoning amendment and enter into a development agreement, effectively a contract, with the company.

“This was really an insult to the public,” Romaniuk said of the board hearings.

For residents like Romaniuk and Allan Akins, who chairs the Springfield Taxpayers Rights Association after many decades working as a federal public servant, “It became very obvious that (the provincial government) was in control,” Akins said.

“I believe there was a push from outside sources that this had to be done immediately, so everything could be passed before the provincial election took place,” he said.

Debate over the proposal and development agreement took place in closed-door, off-the-record council sessions. When council was scheduled to vote on the deal — which had not been made publicly available — residents and media were locked out of the building.

“It appeared the public’s interests were not the first priority for Springfield,” Akins said.

In an email, Springfield Mayor Patrick Therrien said discussions about development agreements are normally — and will continue to be — held off-the-record because they involve negotiations with external parties.

As for public concerns the local council hasn’t been transparent with respect to Sio Silica’s proposal, Therrien said the proposal “is not a secret,” and details were made clear at Clean Environment Commission hearings.

“We at (the) municipal level have taken the brunt of anger from people and groups when this is a provincial government responsibility alone,” Therrien wrote.

In the end, the development agreement was defeated following a tied vote (Therrien and councillor Glen Fuhl voted in favour, while councillors Mark Miller and Andy Kuczynski voted against. Councillor Melinda Warren abstained, claiming she received a threat related to her voting decision). A month later, Sio Silica’s lawyers threatened legal action against the two opposing councillors for “misfeasance in public office.”

“But for councillors’ Miller and Kuczynski’s deliberate and bad faith attempt to disrupt the land use planning process, the development agreement would undoubtably [sic] have been approved months ago,” the lawyers wrote in a letter.

“Any such finding of liability against these two council members would in our view result in vicarious liability for the municipality.”

The letter concluded by demanding council reconvene to approve the development “without further delay.”

Council didn’t reconvene, and as the clock wound down on the timeline set by the municipal board order, Sio Silica filed another appeal, triggering another round of board hearings.

Those hearings were conducted last fall and could result in the province ordering Springfield council to sign the development agreement regardless of municipal or public approval. The board was expected to make a decision by late December, but it’s been delayed indefinitely without explanation.

At the heart of the political drama is a fear among some Springfield residents that Sio Silica’s mine could have devastating effects on their drinking water source.

“Why do any of us spend our time doing this? We’re not looking for something to fuss about — it’s because it matters so much,” Romaniuk said.

In December, Premier Wab Kinew told the Free Press Sio Silica’s mine was likely to be developed, but that the province would first be “backing up a few steps” to review the proposal. Environment Minister Tracy Schmidt said her department is looking closely at the relatively untested drilling method.

Manitoba’s Clean Environment Commission released a report in June that validated concerns from some residents and warned the province against issuing a licence before getting more assurance the project wouldn’t cause irreparable environmental harm. The commission recommended further testing, a legal opinion, a cumulative effects assessment and detailed mitigation and monitoring plans before approving the mine in the long term.

But in the seven months since, there’s been little clarity as to the status of the recommendations.

In an interview last month with the Free Press and The Narwhal, in the wake of the ethical allegations against former Conservative cabinet members, Schmidt was circumspect in her responses on the status of the report.

“There are eight recommendations in the [environment commission] report,” Schmidt said. “One of them was for a legal opinion, that work is done. One is that the minister set up … a monitoring committee. We’re certainly committed to doing that, should the licence be issued. But the remaining six recommendations are all ones that we would envision — should the licence be issued — those would be baked into the environmental licence.”

That means many of the planning documents the commission recommended won’t be seen until after the project gets approved.

In particular, the commission recommended Sio Silica be asked to develop a cumulative effects assessment to look at the long-term impacts the project might have over its proposed 24-year life, rather than assessing the first four years of extraction.

Schmidt wouldn’t say whether that was in the cards prior to the licensing decision — or at all.

“There’s many options on the table,” she offered instead.

As for the legal opinion, meant to settle concerns that drilling through two aquifers to access the silica deposit could be a breach of provincial regulations, Schmidt would not offer details, citing confidentiality.

Asked how she responds to concerns about a lack of transparency in how the province handled Sio Silica’s proposal — and what plans her government has to improve the relationship with area residents — Schmidt said: “There is a lot of transparency built into the process as it exists. I’m sure there are opportunities to make that better, and I really look forward to pursuing that work.”

She did not elaborate on what exactly that work would entail.

As it stands: no decision has been made on Sio Silica’s environmental licence and the department has no timeline as to when that decision might come.

In the meantime, pointing to the political connections and closed-door conversations at all levels of government that have marred the licensing process for residents, Akins said it’s time for an investigation that goes beyond the legislature.

“This is a much bigger issue, it involves a whole bunch of people in high places that are not elected officials,” Akins said.

“In order to cast a broader net and look at all three levels of government and see who had the most to gain — you need a provincial inquiry.”

Updated on Feb. 6, 2024, at 4:17 p.m. CT: This story was updated to correct a typo in the name of the assistant professor of finance at the University of Manitoba. It is Shiu-Yik Au.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

From disappearing ice roads to reappearing buffalo, our stories explained the wonder and challenges of...

Sitting at the crossroads of journalism and code, we’ve found our perfect match: someone who...

The Protecting Ontario by Unleashing Our Economy Act exempts industry from provincial regulations — putting...