86 per cent of a river gone: First Nation calls on BC Hydro to let more water through

Katzie First Nation wants BC Hydro to let more water into the Fraser region's Alouette...

Walking past Jimmie Simpson Park on Queen Street East in Toronto, you can often hear the dribble of a basketball on the concrete court, or the buzz of parents with young children chatting on the grass in the shade of mature trees. Outside the namesake recreation centre, there’s also a baseball diamond, an outdoor rink, and, at the north end of the park, a busy playground.

The park and rec centre sit on the dividing line between Leslieville and Riverside, two neighbourhoods east of Toronto’s downtown core made up mostly of pricey single-family homes, save a few tasteful, low-rise condos. They’ve long been the site of concerts, art festivals and holiday markets. During COVID-19, the rec centre became a pop-up vaccination clinic, while the park is still a spot to eat takeout or gather safely with friends and family.

Jimmie Simpson truly is at the heart of the community. Now, residents fear a proposed transit expansion will ruin it, as existing rail lines on the west side of the park expand with the addition of the Ontario Line, a rapid-transit route being built by the provincial transit agency Metrolinx.

Around six kilometres to the northeast, a very different Toronto community is dealing with similar fears. Thorncliffe Park is a densely populated neighbourhood home to over 30,000 people in just 2.2 square kilometres, most of them in apartment buildings that stretch as high as 42 storeys.

Here, residents say they were blindsided in April, when Metrolinx proposed building a massive maintenance and storage facility to house Ontario Line trains in the heart of their neighbourhood. Spanning around 175,000 square meters, or roughly 24 soccer fields, the yard is set to be located just north of a new Thorncliffe Park station on the Ontario Line — displacing a mosque and 26 local businesses, including Iqbal Halal Foods, the only Islamic grocery store in the area.

Toronto is desperate for transit. It’s set to add another half-million people to its population by 2030, but its aging subway line can barely serve its current population of 2.95 million people, who must endure regular delays and last-minute shutdowns during their daily commutes. But, despite the urgency for more active and public transit, Toronto’s track record for getting transit projects completed is abysmal. New research from the University of Toronto shows it can take as long as 50 years to get from planning to opening day, and over the past half-century, the city has seen expansion plans scrapped repeatedly, never opening at all.

With over 80 per cent of Canadians living in cities, urban environmental solutions like rapid transit play a role in curbing emissions and reaching climate targets. Residents in both Thorncliffe Park and Leslieville-Riverside say they want transit, but as they stare down the Ontario Line, they object to a lack of consultation and straight answers from Metrolinx. They say their public health and community safety concerns have been downplayed and dismissed to the point they no longer trust the provincial agency.

The Ontario government’s four big transit projects in the Greater Toronto Area — the Ontario Line, the Scarborough subway extension, the Yonge Street subway extension to Richmond Hill and the Eglinton Crosstown West rapid transit extension — mark the largest investment in public transit from the federal and provincial governments in Canadian history. That may sound nice, but for Toronto, it comes after decades of cancelled projects that fell victim to government changes and lack of political will.

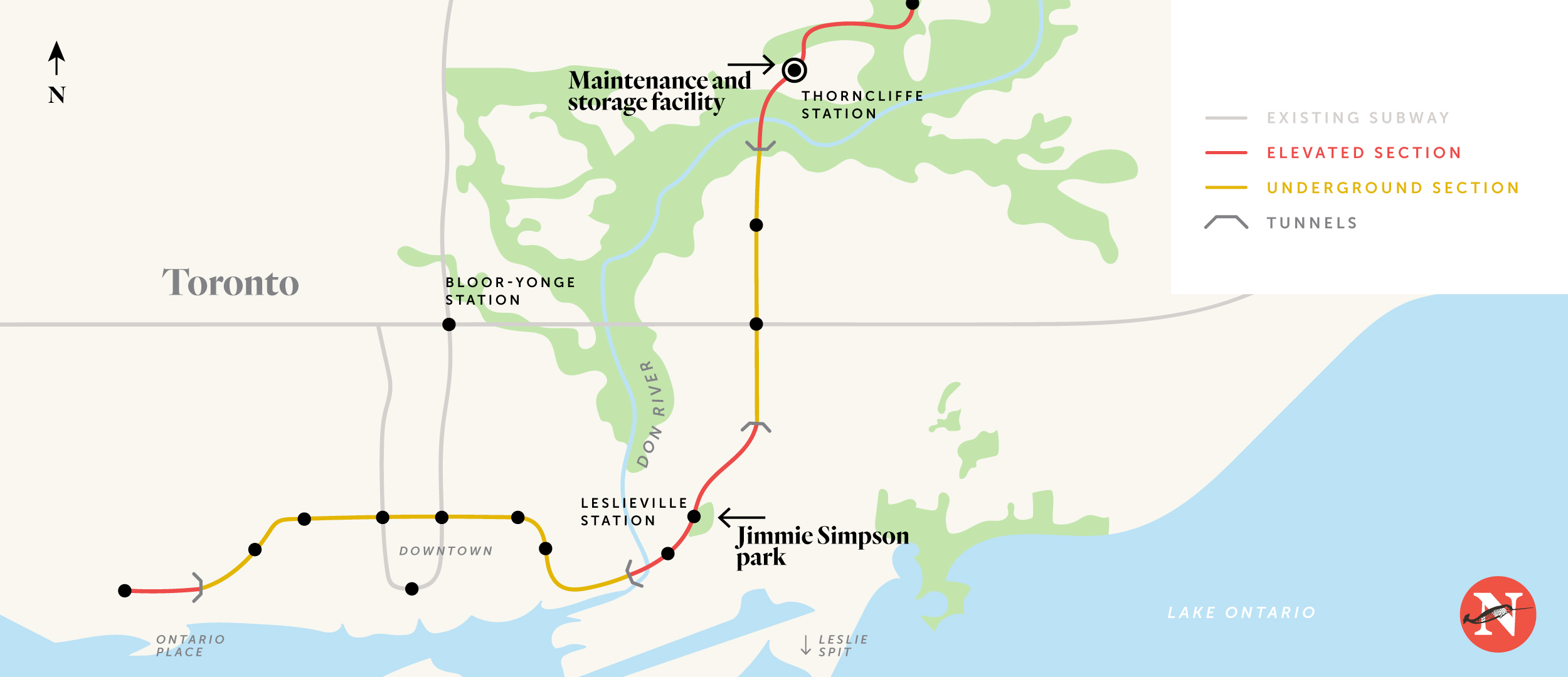

One of these was an underground, eight-stop Relief Line, cancelled when Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservatives took office in 2018. The next year, his government put forward a new plan for a 15-stop, stand-alone electrified rapid transit line spanning roughly 15.6 kilometres, from Ontario Place on Lake Ontario north to the Science Centre, intersecting with the Toronto Transit Commission’s Yonge-University Line 1. Dubbed the Ontario Line, it would be roughly twice as long as the Relief Line, with an estimated cost of $10.9 billion, including about $4 billion from the federal government.

When the Relief Line was cancelled, so was the plan to build entirely underground, with Metrolinx citing an effort to speed up the project. The City of Toronto has requested Metrolinx study the feasibility of an underground Ontario Line more than once in the last two years, but according to the provincial agency, the portion of line through Leslieville-Riverside will be cheaper, quicker to build and have less impact on the community if it’s above ground.

Its plan is to run the Ontario Line on an existing rail corridor west of Jimmie Simpson Park, which currently services Go Transit’s Regional Express Rail lines that run to commuter towns from downtown, in addition to Via Rail and freight trains. This proposal, as well as a planned Go Transit expansion, will require Metrolinx to widen the tracks from three to six and elevate the rail corridor, in addition to rebuilding and adding new bridges along this portion of the route.

On the other side of the tracks from Jimmie Simpson Park is Wardell Street, which curves to meet De Grassi Street, the namesake of the fictional Canadian adolescent drama Degrassi Junior High. Both streets feature the kind of stately brick houses you can only find in the oldest parts of Toronto. For two decades, house prices here have shot higher, and then higher, and the surrounding community has garnered international attention for its understated but historic architecture, a long list of restaurants, laid-back cafes and local shopping. It’s a snapshot of a trendy Toronto neighbourhood.

Fifty metres or fewer from the rail corridor are the bedrooms and living rooms of a few dozen homes. That includes the semi-detached house where Eon Song lives with his partner. Before they bought it five years ago, the couple went to a viewing armed with decibel meter apps installed on their phones to test the noise of passing trains from inside. The meter shot up by 15 decibels when a train passed by, but Song thought if the whole street was dealing with it, it must be okay.

Now he’s a member of Save Jimmie Simpson, a group formed last year by about 10 local residents to challenge Metrolinx and the above-ground plan through their communities. The group estimates that once both the Ontario Line and Go expansion work are complete, a train will pass well over 1,500 times a day.

“This comes from our manual calculation based on what little information Metrolinx has given us,” Song said. By The Narwhal’s calculation, this amounts to roughly one train every minute if the trains were running 24 hours a day, and more frequently if the trains were only running 16 to 20 hours a day, passing metres from the homes on Wardell Street. Metrolinx did not confirm or dispute the Save Jimmie Simpson calculations.

These two urban East Toronto communities feature historic homes and sites.

An above-ground section of the Ontario Line, widening the existing rail corridor, and adding or rebuilding train bridges along the route. Leslieville station will be built at Queen Street East and Degrassi Street.

Homes are around 50 metres from some parts of the existing track and residents fear Jimmie Simpson Park will be impacted.

Save Jimmie Simpson estimates there could be as many as 1,500 trains a day on the tracks by 2030 once the Ontario Line and expansion work are complete.

In early 2020, Save Jimmie Simpson requested a federal impact assessment of the Ontario Line from Health Canada. In February 2020, the federal department denied the request, citing a lack of jurisdiction. But its response also outlined omissions in Metrolinx’s Environmental Compliance Report for the Ontario Line, a report meant to give a broad scope of the agency’s plans and potential impacts based on regulations.

Health Canada wrote that Metrolinx “does not discuss the potential for human health risks” in a number of areas, including “exposure to diesel particulate matter” during construction, “changes in noise from construction and operation activities” as well as “the potential for cumulative effects on human health.” It also said the report “includes only a brief summary of the potential project impacts on environmental and socio-economic conditions and proposed mitigation measures.”

Although Health Canada noted inadequate identification and description of human health impacts for the Ontario Line, it didn’t provide an opinion on the project. In an email, Metrolinx spokesperson Anne Marie Aikins said the Health Canada report “ultimately determined our existing environmental assessment process for the Ontario Line provided ample oversight for the project.”

Song filed a complaint with the provincial Ombudsman’s Office, and in February 2021 Metrolinx responded with a letter, saying that studying health impacts was outside of its mandate as a transit agency. It advised that potential air quality, noise and vibration impacts will be part of an eventual environmental assessment, which will likely be released in winter 2022, and that community concern had led to plan adjustments meant to protect the rec centre

Save Jimmie Simpson is fundraising to commission an independent health impact assessment. It’s expected to be released early next month, and the group has raised over $14,000 of its $20,000 goal.

“If you cannot put it underground and find alternative routes, then identify which homes would be not fit for living, either noise measurements, vibration, whatever the case may be, expropriate those homes. That’s it,” Song said. “I think this government has an obligation to build transit that works, that makes sense, whoever lives here.”

Hundreds of neighbours have attended rallies, signed petitions and fundraised for Save Jimmie Simpson’s efforts. One of their worries is losing parts of the park. In a June 2021 blog post, Metrolinx said the park, playgrounds and existing buildings can operate during construction and beyond, and that the three additional tracks will fit within the existing rail corridor. The agency stated the project will actually result in 2,600 square metres more green space in Jimmie Simpson and other parks along the route.

But a community member for Save Jimmie Simpson took Metrolinx’s drawing of the tracks and superimposed them on an aerial photo of the area, creating a rendering that shows homes and businesses will need to be removed, in addition to trees and parkland. The agency says the community’s rendering is not accurate and it’s own technical drawing of the same corridor through Leslieville-Riverside looks quite different: in it, all construction is kept within the rail corridor boundaries, which are generally indicated by the existing fence and retaining wall on either side.

Local residents are also worried about noise and rumbling. In its February letter to Song, Metrolinx said that it believes that the majority of noise and vibrations from the Ontario Line can be mitigated by a planned barrier, but that additional measures might be explored after noise studies and the environmental assessment. In late September, Metrolinx released a noise and vibration study for the Lakeshore East corridor. It was part of a draft of a report that also suggests mitigation measures for the construction period, including doing work during the day when possible, and using silencers and diesel mufflers on equipment. The public can review and comment for roughly a month, which may or may not be considered in the final report.

The noise levels within the draft report are based on readings from receptors placed outdoors, near the line, and only show the likely effects of the Ontario Line and GO transit, excluding the potential cumulative effects of Via Rail and freight trains. The receptor on Wardell Street showed an average reading of 64 decibels during the day, while another, further east on Pape Avenue, peaked at 73. Interpreting noise readings can be challenging, but normal conversation is about 60 decibels and a motorcycle engine running is about 95 decibels. According to Health Canada, noise above 70 decibels over a prolonged period of time can lead to hearing loss.

The same day the report came out, the agency held an online consultation, touching on its plan to build a noise barrier. The community has a say in what the wall will look like but has not received answers on its potential height or exactly how it will absorb the noise. In a March blog post about noise barriers generally, the agency wrote that most of its barriers are five feet high and made of a concrete composite.

Aikins said that the agency follows Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks guidelines for assessing noise limits, which only apply to outdoor locations, and don’t cover noise inside homes or businesses. The agency maintains that despite an increase of trains in the corridor, it is actually forecasting lower noise levels in most Ontario Line areas after the corresponding noise walls are built.

In other neighbourhoods near above-ground subway tracks, noise has been cause for concern. In 2019, Dr. Vincent Lin, an otolaryngologist with Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, told Global News that subway screeching in Etobicoke posed serious risks to nearby residents. His analysis was based on a 2017 study that he and a team published in the Journal of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, which concluded that while the average noise levels from Toronto’s transit are within the level of safe exposure, noise-induced hearing loss was a possibility for those who are exposed often.

The agency says the environmental assessment will come before early construction begins next year, with the bulk of the work scheduled for 2023. Metrolinx plans to begin removing trees within the rail corridor this fall or winter, though Aikins said no trees will be removed outside the rail corridor “until later in 2022.” Until then, Song says, nothing is set in stone. Save Jimmie Simpson is hoping to stave off tree clearing and preliminary work until the environmental assessment is done.

While tree-clearing and early construction is imminent, Shoshannah Saxe says the completion of the project could take a while yet. An assistant professor in the department of engineering at the University of Toronto, Saxe holds the Canada Research Chair in Sustainable Infrastructure.

In August, she and a team of researchers released a report comparing the timelines of 26 transportation infrastructure projects in Toronto and London, England. “In both cities more than half of the preconstruction time was on average spent in political rather than technical processes,” the team wrote, finding that it took about 18 years for a proposal to translate into shovels in the ground.

And it can take a few more decades after that to reach opening day in Toronto: recent projects have taken half a century to make it from the idea stage to accepting riders. “One version seemed like it was gonna happen, maybe you liked that version, and now we’re back to an earlier stage, it’s happening again,” Saxe said.

Steve Munro has been a transit advocate in Toronto since 1972: on his namesake website, he shares photographs and writing about transit projects in the city and across the province. His knowledge of local transit is both broad and deep. He thinks Metrolinx has an opportunity to build meaningful projects, linked with development, shaping neighbourhoods as they grow — but that the agency is blowing that opportunity by, as he said in an August phone call, “being so damn secretive and pissing everybody off.”

The retired IT professional believes Metrolinx is trying to get “as much beyond the point of no return” on the Ontario Line before next spring’s provincial election, and the risk of a new government scrapping the plan, again. “I think Metrolinx’s general attitude is to find a way to get around the community,” he said. His own calculations of train frequency based estimate about 1,800 a day through the Jimmie Simpson corridor, though each train passing through is not equal (a diesel hauled Go Transit train will make more noise than the electrified cars set to be used for the Ontario Line).

“Metrolinx has been around for a long time now and it could have been so much better than it is,” Munro said. “It’s sort of the Ford transit legacy, if you will.” The agency was fairly new in 2010 when Rob Ford, Doug’s late brother and then-mayor of Toronto, cancelled yet another previous plan for new rapid transit lines across the city. Then Kathleen Wynne’s Liberals were ousted by the provincial Tories in 2018. “And Metrolinx, who were on shaky ground politically, pivoted and turned themselves into Doug Ford’s construction company.”

Munro believes a regional transportation authority could, in theory, connect people, operate “truly collegially,” and actually get much-needed transit built. He doesn’t feel that has happened in the communities currently facing an Ontario Line project, including Thorncliffe Park.

That’s the neighbourhood Aamir Sukhera has called home since 1981. He’s one of many in the community that say no one was consulted or notified before the spring announcement of the maintenance and storage facility — not even local elected officials.

There’s a new Thorncliffe Park station planned for the Ontario Line, which would serve the community well. Right now, it takes 15 minutes to get to the subway by bus, and then another half hour to get downtown, often longer in rush hour. The storage yard, set to be just north of the new station, was announced by Metrolinx in the spring.

“For three years, you never once mentioned that you’re going to put a train yard here, it was only the train station. And all of a sudden you decide this is the only location that it can go, but you’re not talking to us about it,” said Sukhera, who works in cyber security. Metrolinx told The Narwhal it chose Thorncliffe Park for the facility after reviewing nine locations because “it was the only option that could meet all of the technical needs for the project.”

Sukhera says he’s grateful for the incoming Ontario Line, and agrees it’s a desperately needed connection to the rest of the city. But he’s worried about how the loss will affect people who rely on the services in the plaza, which houses a grocery store as well as The Neighbourhood Office, a community hub for employment, health and social services.

“There’s a known problem in our community, there just isn’t enough space for everyone and taking away 600,000 square feet isn’t the right thing to do,” Sakhera said.

Sukhera is part of SaveTPARK, a group with around 40 core members, which is trying to find a solution. Instead of the planned site, the group has proposed a hybrid option, splitting the storage facility into two locations, plans they say Metrolinx has not seriously considered.

“So just hear us when we say: move this, you can, the city is big, there’s so many other places, and we’ve given you the perfect place to put it. Respond to why that’s not a good enough site that we’re proposing. And they haven’t,” says Sakhera, who has heard some people refer to the site location, and lack of consultation, as environmental racism. The 2016 census indicates 79 per cent of Thorncliffe’s residents are a “visible minority” and the rate of poverty here is 46 per cent, more than double Toronto’s average.

As in low-income communities across Canada, COVID-19 devastated Thorncliffe Park. But when vaccination pop-ups brought the community together, SaveTPARK saw an opportunity to inform people of Metrolinx’s plans. English is not the first language of nearly three-quarters of the community, and many were unaware of the rail yard proposal. The group translated its messaging into 15 languages and says that over the course of their advocacy, more than 10,500 residents and supporters signed their petition. On Oct. 6, members from SaveTPARK joined Save Jimmie Simpson and other community groups on the lawn in front of Queen’s Park for a rally.

Also on the future site of the rail yard is a community-funded mosque, which Suhkera says was struggling after a bad business decision when it was approached by Metrolinx. He says the agency allegedly paid $20 million to expropriate the building, which is roughly 10 times the annual revenue of the Islamic Society of Toronto, the organization that runs the mosque, according to public information.

“In my conversations with the mosque leadership, I said, ‘we ought to ask people how they feel.’ And the response was, ‘They’re just renters, so what does it matter?’ And that is where I think I made my decision to stand up for this because I am also a renter, I’ve been renting here all my life,” Suhkera said. While about half of the people in Toronto own a house, almost all of Thorncliffe Park consists of renters, with most calling one of 34 apartment buildings home.

“That mentality, that people who don’t own don’t matter, is not right. You could be the poorest person here, but you’re still part of our community and we’ll look after you,” said Sukhera, who feels the mosque and its leadership have been given preferential treatment in the Ontario Line process. “I don’t want to make this whole thing about the mosque because it truly isn’t, it’s Metrolinx, but they’re a significant part of why this is happening and how communities get sold out by those that people think represent the community.”

This densely populated low-income neighbourhood is home to 30,000 people in 2.2 square kilometres.

A 175,000 square metre maintenance and storage facility to service and store trains on the Ontario Line.

The site of a plaza currently home to a mosque and 26 local businesses, including the neighbourhood’s only Islamic grocery store.

SaveTPARK says there was zero community consultation prior to publicizing the final site.

The mosque’s treasurer, Illyas Mulla, said in an email response to The Narwhal that it signed a non-disclosure agreement with Metrolinx, and wouldn’t respond to further questioning. “We are not pressured by Metrolinx or anyone else,” Mulla wrote, criticizing “misinformation” and “misinformed people.”

Metrolinx says it plans to try to help relocate impacted businesses, but it’s unclear how close they’ll be — if at all — to the community they currently serve. The agency said specific details and financial figures are confidential.

“There is impact, but that impact isn’t significant enough for Metrolinx or the mosque or even the politicians who care,” Sukhera said. “I don’t want them to think that we should just roll over and accept whatever is given to us. We have to at least try.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Katzie First Nation wants BC Hydro to let more water into the Fraser region's Alouette...

Premier David Eby says new legislation won’t degrade environmental protections or Indigenous Rights. Critics warn...

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...