Rocky Mountain coal mine in Alberta takes next step to expansion

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

Josie Osborne seems careful with her words as she talks about her new job. The former mayor of Tofino, turned MLA, is heading up the new B.C. Ministry of Land, Water and Resource Stewardship and is the minister responsible for fisheries. But through her political composure are glimpses of a lifestyle associated with the little west coast community on Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation territory — she lives on ten acres with her husband, dog, three goats and chickens and works out of a brightly coloured tiny house office.

She has a clear love for coastal ecosystems and notes her appreciation for the likes of the once-endangered sea otter, “because it’s a keystone species that teaches us a lot about the interconnection of different habitats and species in the marine environment.”

Osborne first moved to Tofino in 1998, just a few years after the region made national headlines during the infamous “War in the Woods,” one of the largest acts of civil disobedience in Canadian history. Fresh out of graduate school, she worked as a fisheries biologist for the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council. It was here that she first came face-to-face with conflict around resources, environment and Indigenous Rights in terms of the impacts of fish farms on wild salmon populations.

Later, she worked with a local environmental education non-profit and served as mayor of Tofino from 2013 to 2020.

After resigning as mayor, she threw her hat into provincial politics and was elected NDP representative for Mid Island-Pacific Rim that same year. In February, Premier John Horgan appointed her to the newest portfolio in his cabinet.

The bureaucratic shakeup divides the bulk of responsibilities formerly shouldered by the “super-ministry” of forests, lands, natural resources and rural development between Osborne’s new ministry and a standalone Ministry of Forests, punting the remainder to existing ministries.

In a statement accompanying the announcement, the office of the premier said the restructure was necessary and a “natural evolution of land and resource management in B.C.”

“These changes are needed to advance meaningful reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples, grow the economy and ensure a sustainable environment.”

Osborne calls the inclusion of the word “stewardship” in the new ministry’s title a subtle but important distinction and links it to an Indigenous worldview. She is acutely aware of what it means to live and work under First Nations’ jurisdiction — in 2014, the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation’s Ha’wiih (Hereditary Chiefs) declared the territory a tribal park, a fact she speaks of with pride.

From her eclectic office, Osborne spoke with The Narwhal about the roles and responsibilities of the new position and her vision for a ministry that is poised to be at the forefront of often-thorny issues where environment, development and reconciliation intersect.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

They’ve been incredible, actually. I am very honoured to receive this appointment from the premier. To lead the formation of a new ministry is no small thing. It really is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

I think the new ministry really expresses our commitment to the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and truly represents a new way of looking at land and resource management in British Columbia. It’s a big file — I have a lot of hope and I know there’s a lot of hard work ahead.

These first few weeks have really focused on my outreach to First Nations, to industry and to communities to understand the landscape before us and all of the opportunities.

I think it’s really important to reflect on the fact that it’s important to do this work well, and that we do this work right. And some of it will take time. I’m really proud of the fact that I’m part of a government that has passed the DRIPA legislation and has really codified our intent and our goals in working with First Nations to really transform, in my case for this new ministry, the way that we steward the resources on the land base. The commitment is there, the commitment is so strong. Because we all want to see the natural resource sector support reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples, we know that means balancing and prioritizing ecosystem health and environmental sustainability, as well as balancing the economic opportunities that resource stewardship provides for people across B.C.

We have to decide together what the best ways are to permit different activities and to enable those opportunities for people. In the action plan we have four specific actions that the new ministry is leading on and one that we’re supporting the Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation on. It really characterizes the collaboration that we need to do, the work we need to do to gather with First Nations on strategies and programs for things like protecting and revitalizing wild salmon, advancing more sustainable water management and addressing cumulative impacts on the land base — the cumulative impacts of decades of industrial activities on First Nations’ traditional lands.

There is a lot of collaborative work going on already with First Nations on addressing, well, all kinds of resource use but also the need for protected areas. And although I can’t tell you a definitive outcome of that kind of work, I can tell you that the collaborative work we’re doing at different stewardship tables, with First Nations and across different programs and initiatives, is very much a part of that work.

I will say on a personal note, too, I live in Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation territory, which has been declared a tribal park for decades now. The current concept of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas and what that means for First Nations, and for British Columbians, is something I think we’re all coming to understand more and getting a greater awareness of the opportunities there. I think it’s very exciting work and work that I’m really committed to doing.

It’s the work we have to do together as almost two societies are coming together on two different worldviews about our relationship with the natural landscapes. In the Nuu-chah-nulth culture, as I have learned, there is no word for wilderness. There is no concept of a landscape that is absent or devoid of humans. Humans have a relationship with the landscape and the resources on the lands everywhere. I think the opportunity that IPCAs bring us is sort of redefining that relationship between what a protected and conserved area is and how we can still allow for human use and human relationships to the landscape and to the resources that that landscape provides. But doing so in a way that doesn’t ignore the role of humans.

Maybe I’ll just come back to looking at the title of this new ministry: Land, Water and Resource Stewardship. It’s not resource management. That’s a really important, if subtle, change because “steward” in the sense of taking care of, and really reflecting that human relationship to the landscape. I think it’s really important and will be one of the things that we really get to explore as we understand better what IPCAs are and what they mean for all of us.

Part of the mission of this ministry, in really developing that overarching and more strategic look at land use from the oceans, through the rivers and up onto the land base, is recognizing that connection with different species and doing the things we know we have to do to protect, to conserve, to restore and to revitalize species at risk. It’s not to say that legislation is off the table, but we need to do the work with First Nations in coming to those decisions and working together with them. In time, there may be a case for endangered species legislation.

I very much understand and feel that tension between the urgency with which we must take on any number of files and programs and initiatives with the need to do it well, to do it right and to do it together, collaboratively with First Nations. There are already examples of where steps are being taken to protect species, whether designated at-risk or not, and ecosystems. I think the old-growth strategic review is a good example of that and the commitment that our government has made to implementing all 14 recommendations of the review, including placing biodiversity and ecosystem health as that overarching prioritized principle. We need to take action immediately with certain species, and we’re doing that, but also we need to build out that framework that prevents us from getting into this place in the first place.

My opinion has not changed much from what I’ve said in the past. I think, first and foremost, the preservation and conservation of wild salmon is something that is important to me and to every British Columbian. I’ve never met a British Columbian who didn’t understand the cultural importance of salmon, the physical importance of salmon and, really, the symbolic importance of salmon. Almost every part of British Columbia is touched by salmon in some way, shape or form. And we have seen over the decades the impacts on fish habitat, the impacts of climate change on ocean productivity and impacts of other coastal uses, including salmon farming and other activities that have taken place.

Again, it’s that tension between the urgency with which we must act — we see that in too many small stocks that are at risk of being lost forever — and just how challenging it’s been to balance the needs of different groups. What I think is hopeful and new is that commitment to working with First Nations collaboratively on wild salmon preservation and conservation, and the need for all parties to be at the table to do this together. Every order of government has some jurisdiction around wild salmon, whether it’s making decisions about commercial fishing rates or habitat-related issues, water quality issues.

Whether it’s local government, the province, the federal government and even we as citizens in our daily lives, we’re all making decisions that affect the health of wild salmon.

I think we have an opportunity now by bringing almost all of the fisheries-related functions in the province of British Columbia under one roof, appointing one minister to be the point person for Fisheries and Oceans Canada, as well as for communities and for First Nations, to work on these issues together to really make progress. Throughout my career, I would say I have really found that by bringing people together in conflict — and certainly I think wild salmon is an example where we experience a lot of conflict — if we sit down and do the hard work together, we can actually make better decisions and save these iconic species.

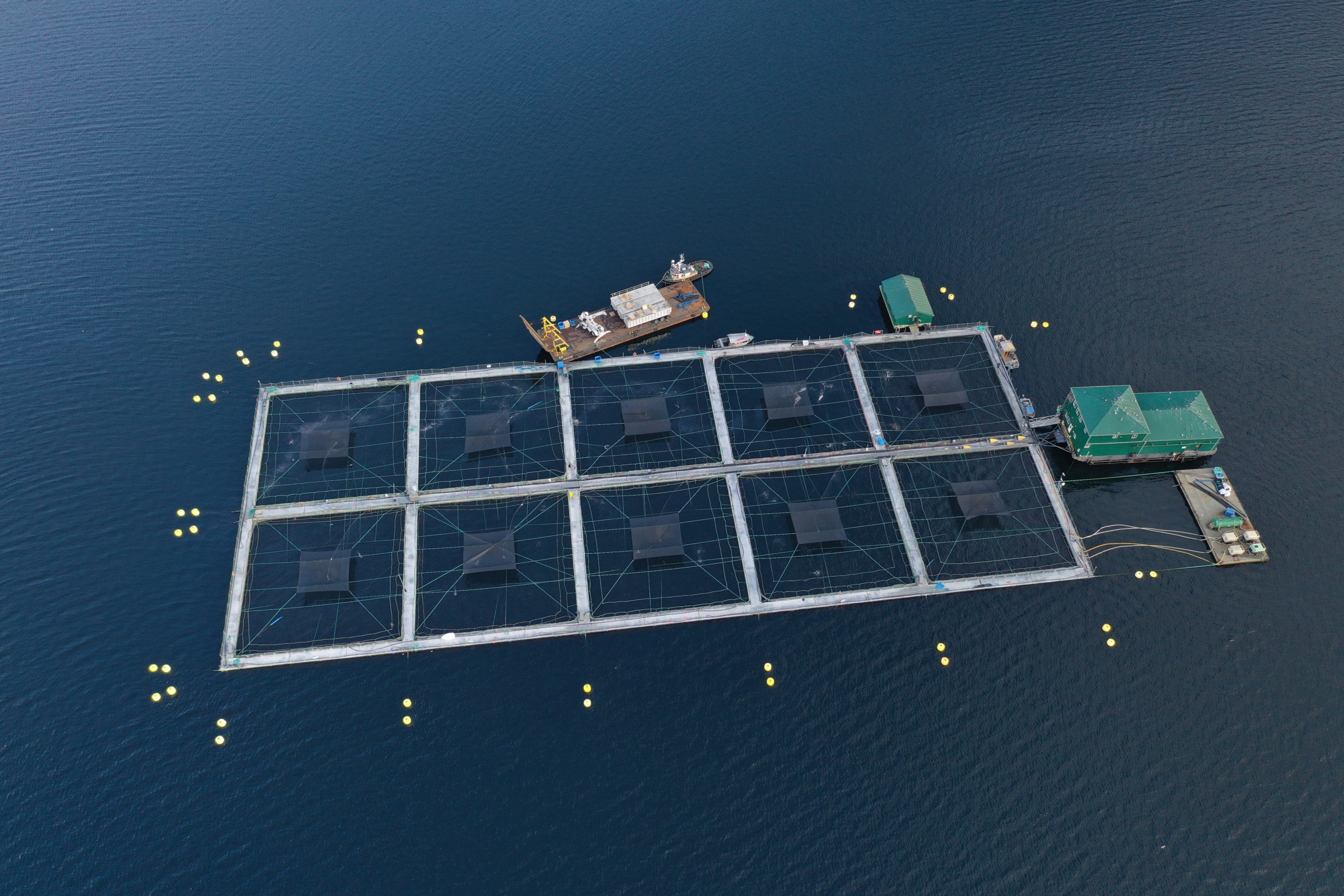

I’m going to answer that question by first starting with a really short story, which is that when I first moved to Tofino to work as a fisheries biologist, I was fresh out of graduate school so I didn’t have any direct experience working in communities. One of the first things that I got thrown into was a big conflict around open-net fish farming, salmon farming in Ahousaht territory. There were several companies working at the time — back in that day, we sort of referred to it as a bit of the Wild West when it came to salmon farming. It was in its relative infancy and there was a lot of mistrust and misinformation, as well as a very valid concern about the impacts of open-net salmon farming on wild fish stocks and on fish habitat.

What we did was bring together the federal government, the provincial government, industry and the First Nation, together with a few folks like me as supporting technical staff and began to meet on a regular basis and really hashed out what it was we valued and were concerned about. That included not only the preservation of wild fish and habitat, but also the value of jobs. Over time we came to a situation where the First Nation was able to strike a protocol agreement with the remaining companies in their territory.

What I really learned from that was, although I didn’t always necessarily agree with the outcome of decisions, when we brought everybody together we were able to make those better decisions and to really understand the trade-offs. I see that being played out again, here. We saw in the Broughton Archipelago process immense value when First Nations, very validly concerned about open-net fish farming in their territories, came together with the industry and the province. People were able to be explicit about their values and the trade-offs that they needed to make.

Once again, I think with the upcoming decision that the federal minister needs to make, that’s exactly what we need to do again, that is, bringing together all parties and having the difficult conversations. It will take understanding that under DRIPA we have an obligation to support First Nations in determining their futures and working together to conserve wild salmon, but also to provide economic opportunity. So I won’t predetermine the outcome but I will say that I’m incredibly committed to that process and that I know from personal experience it can work.

The role that I see myself and the province playing is ensuring that First Nations and communities are engaged and consulted in a meaningful and principled way. And that any transition or change that takes place is done in a way that is responsible and dignified and fair. This isn’t about being afraid of change, it’s about making sure that the change happens in a way that enables people to continue living their lives. We’ve already heard from a number of communities that are dependent on fish farming as part of their coastal economy and we all have a responsibility to work together to support those communities as those coastal economies change. I think that’s a really important role for this new ministry. Through the creation of British Columbia’s first coastal marine strategy, looking at what opportunities are available to help support coastal communities, but doing so in a way that’s congruent with their values and the activities that they want to undertake. And again, keeping in mind the overarching principle of ecosystem health, biodiversity and enabling activities that can happen under that.

I’ve been thinking about this for 25 years. When I was the mayor of Tofino, when I was a fisheries biologist working for the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, I saw this play out all the time — the polarization. When we focus on polarization, I think we fall into this trap of not being able to see solutions because we’re so focused on the ends of the spectrum. I have spent my career, no matter what I’m doing, focused on building bridges, bringing people together and trying to use good communication techniques done respectfully, with good listening, to help people understand the values that we all share. And I do think that British Columbians share a lot more than we might otherwise think if we only read Twitter, or sometimes the news.

I am going to continue to be as patient and methodical and committed and respectful as I hope that I always have been in bringing together different groups. I feel like now I’m just operating on a bigger scale. It takes a lot of work and it takes a lot of patience and I think it takes a lot of integrity on the part of all people. But I will tell you, over these 25 years, time and time again, I have seen it work and I’ve seen us make progress.

I think that this new ministry is very much set up in that way as well. This is the first time that different parts of the natural resource sector ministries have been realigned in a way that we can really take that cross-sector approach and focus on co-developing solutions with First Nations, which I truly feel is going to put us all in a better place.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...