B.C. has a new policy for staking mining claims. Why doesn’t anyone like it?

B.C. previously allowed mineral claims without First Nations consultation. It was court-ordered to fulfill its...

Author’s note: Ray Williams, Ghoo-Noom-Tuuk-Tomlth, passed away just two months after he was interviewed for this story — on October 31, 2022. This story is dedicated to his memory. Like the coastal wolves Ray was named for, he was highly aware, family orientated and protective of his territory. Let his spirit live on.

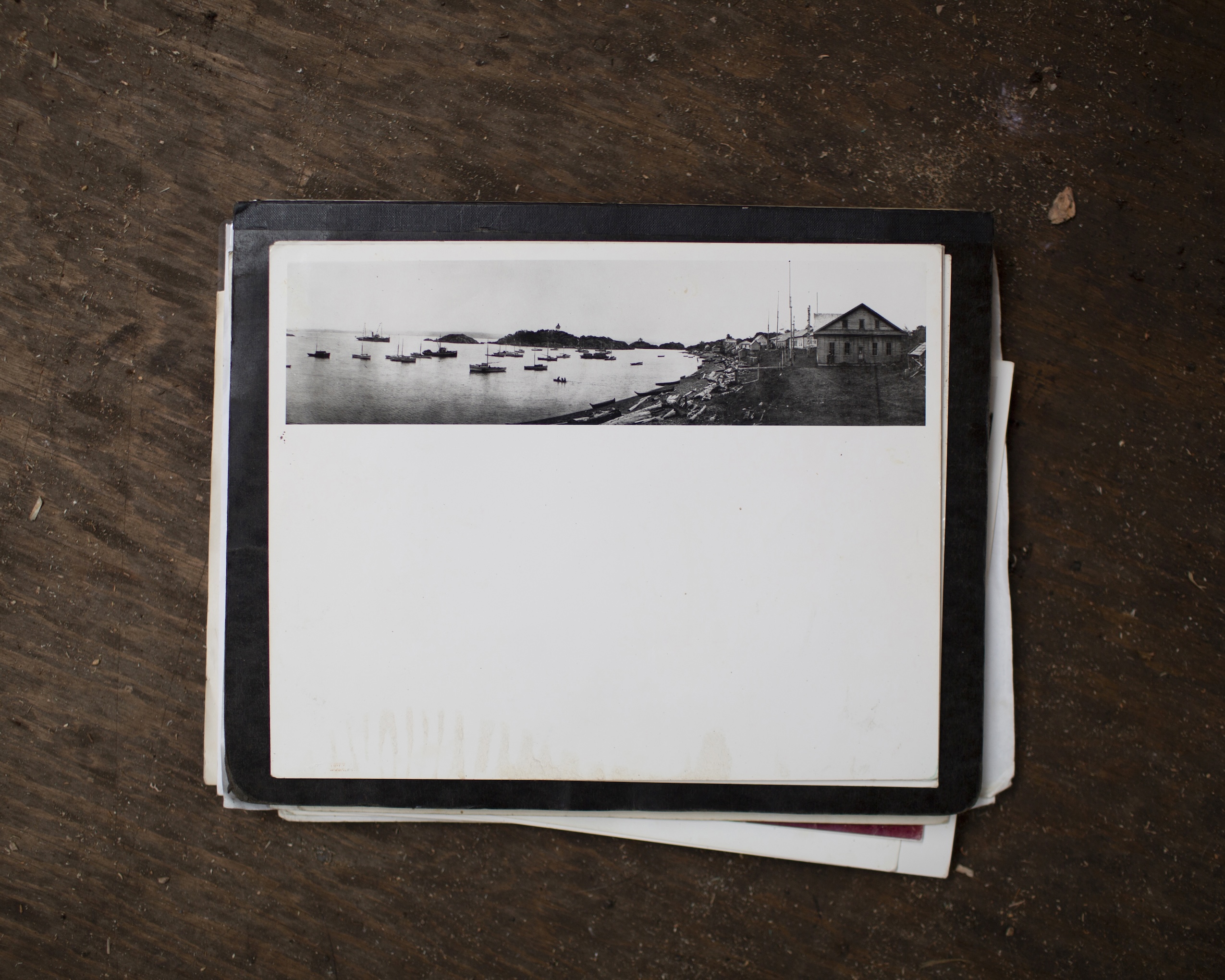

Ray Williams recalls the day Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) confiscated all the Mowachaht boats from Yuquot — his hometown and ancestral territory on the southeast tip of Nootka Island — in the 1960s.

“There were still a few boats left on the beach that day,” said Ray. “But the DFO came and burned them.”

With no prospect of earning a living, most of the community was forced to relocate to reserves near Gold River on Vancouver Island. Before long, Ray became the last remaining Mowachaht/Muchalaht to live in Yuquot year-round.

Ray was 80 years old during an interview in August 2022. A pillar of the remote Yuquot community and Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation, Ray also holds the name Ghoo-Noom-Tuuk-Tomlth, which means “spirit of the wolf.”

As he tells his story from the small wooden house on the beach — the same one he grew up in — he looks out to sea and the memories rush over him like the tide. Memories of secret fishing spots, plentiful food and a way of life stripped from him and his family.

Although Ray and other Nuu-chah-nulth people have witnessed some progress on fishing rights — thanks to a landmark court case led by five Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations — it hasn’t been enough to break the cycle of harm caused by Canada’s forced control over fish management in their unceded homelands.

This disconnection from a keystone of Nuu-chah-nulth’s culture, territory and ancestral wealth — stemming back to the creation of the colonial capitalist fishery — has permeated through generations.

Sammy Williams, Ray’s grandson, has grown up seeing his grandpa criminalized for trying to earn a livelihood through fishing in his traditional territory. Like his grandpa, Sammy has struggled to keep on the “right” side of colonial law.

One of Sammy’s earliest memories is of a strange, white authority figure removing his grandpa’s longline and taking his fish supper away. It was a fisheries officer from Fisheries and Oceans.

“This is what they do,” said Sammy, now a rights-based commercial fisher.

Even though he was just a child at the time, Sammy remembers that day clearly.

“We headed out there waiting for the hours to go by,” he said. Sammy and his grandpa spotted a sailing boat edging towards their long line.

Working undercover in an unmarked sailing boat wasn’t normal practice for Fisheries and Oceans. “I seen him take two halibut off, put them in his boat, took my long line away and put it in jail in Tahsis,” said Ray. “Two years later, they gave it back to me.”

In an email commenting on the events shared by the Williams family, Fisheries and Oceans acknowledged: “The memories shared by Ray Williams about his experience of DFO’s past relationship with his community are painful.”

The department also highlighted its commitment to “reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples” and said they are committed to working with First Nations “to increase their participation in the fisheries and to support the exercise of their rights.”

“In more recent years, efforts and progress have been made towards rebuilding a nation-to-nation relationship with First Nations, including the Mowachaht community, based on the recognition of rights, respect, co-operation and partnership,” the statement said.

“Today, DFO works closely with the community through collaborative programs, such as the Aboriginal Fisheries Program (AFS), consultation, bilateral meetings and other means, to collaboratively manage fisheries and protect fish and fish habitat.”

Long after the Mowachaht boats were confiscated and burned by Fisheries and Oceans, Ray said vessel owners were compensated with $7,000 per household, “to keep us silent about our fishing rights,” he said. “It wasn’t just their livelihood that was taken, but their identities as fishermen.”

Sammy stressed that $7,000 is barely enough to compensate for the destroyed fishing vessels. “It buys you a skiff, not an actual boat,” he said. IndigiNews did not independently verify this settlement amount.

“When they did that to our Elders, they took away fishing for our generation,” said Sammy, who learned to fish commercially from settlers. “We could have been on the water with our grandpa and my dad, learning the right way.”

When Sammy first entered the world of commercial fishing, he “got in with one of the wrong guys,” he said, referring to the infamous rule-breaker Scott Steer, who has been convicted multiple times for illegal fishing and now faces a lifetime ban.

Before long, Fisheries and Oceans had seized Sammy’s boat and truck. “Pretty much what they did to my grandparents back in the day,” said Sammy, who began to feel as though history was repeating itself.

Before colonization, the Mowachaht/Muchalaht people were wealthy fish traders, with abundant territories and carefully-managed fisheries that made returns year after year. With the introduction of colonial commercial fisheries, the resource was exploited to feed a capitalist system hell-bent on making a profit.

Even though colonial officials had no ancestral ties or expert knowledge about these lands, animals and waterways, they began using the force of colonial law to “manage” the resource above the expertise of Indigenous locals.

In 1877, the federal Fisheries Act was extended to all of British Columbia. For the first time, “food fishing” was defined and imposed as a limitation on what Indigenous Peoples in the province could, and could not fish for.

It became illegal for Indigenous people to fish for any harvest amount that could be interpreted by imposed colonial standards as more than what was necessary for eating. The act also required all Indigenous people to purchase a fishing licence, and outlawed traditional fishing technologies such as weirs, spears and hooks.

A handful of court cases have attempted to uphold Indigenous Rights to fishing for a livelihood. Where there’s been success, Canada has been criticized for not properly implementing them.

In 1987, Dorothy Van der Peet, a Stó:lō woman, was charged for selling 10 salmon for $50, caught by her husband and brother with a food fishing licence that forbade them to sell their catch. At trial, the judge held that the right to fish did not extend to the right to sell. Van der Peet appealed her conviction, but in 1996, the Supreme Court of Canada dismissed her appeal.

Although the case was a loss for Van der Peet, it became pivotal in further defining Indigenous Rights, as outlined in Section 35 of the Constitution.

In 1996, the Supreme Court deliberated on the landmark Gladstone case, involving two Haíłzaqv (Heiltsuk) men who faced charges under the Fisheries Act for exceeding their licensed allowance in selling herring roe-on-kelp — a traditional annual resource where herring eggs are attached to kelp in the water column.

It was ruled that the Haíłzaqv have a right, based on traditional practices, to sell or trade fish. But when the chief justice failed to decide whether the licence available was adequate for a “sustenance” income, they sent the question back to trial. It has not been continued.

In 2003, 13 Nuu-chah–nulth nations began a court case to prove their right to a commercial fishery. But after pushback from the federal government, who refused to allow the 13 nations to participate without defined ocean territories, five nations pursued the claim, including Mowachaht/Muchalaht, Ahousaht, Ehattesaht, Hesquiaht and Tla-o-qui-aht. The group became known as the “Five Nations.”

In 2009, a ruling found the Five Nations had a commercial right to harvest and sell fish. The ruling also stated the Five Nations must negotiate with Fisheries and Oceans on how their commercial fisheries would be managed. The court allowed two years for negotiations, but an agreement was never reached. Fisheries and Oceans continued providing a limited allocation and restrictions on how the Five Nations could fish.

In 2018, the Five Nations went back to court, stating that Fisheries and Oceans was infringing on their court-affirmed rights to fish commercially. But in an unexpected move, the chief justice limited the right that had been affirmed, describing the fishery as “artisanal” and “local” — only to be carried out using small boats with no technology.

The Five Nations appealed, and in 2021, the B.C. Court of Appeal concluded all previous limitations would not be accepted. Again, fisheries were to be negotiated between the Five Nations and Fisheries and Oceans, and their rights-based fisheries were to take priority over the recreation and commercial sectors.

The ruling set a precedent for Indigenous fishers across Canada, who can now negotiate their right to sell fish with Fisheries and Oceans — without the lengthy and expensive court battle endured by the Five Nations.

However, a legal precedent doesn’t necessarily mean immediate changes out on the water. In 2021, just days after the B.C. Court of Appeal ruled that Fisheries and Oceans could not impose limits on First Nations commercial rights, rights-based fisher Harvey Robinson from Ahousaht was stopped by officials trying to land 250 fish. He was told to get rid of 240 — he was only allowed 10.

After some confrontation, Fisheries and Oceans walked away. Robinson said they were trying to impose the 10-fish rule, which applies to boats under 25 feet. But his boat was 42 feet.

“Ten fish wouldn’t cover the gas bill,” said Sammy. “Let alone ice, food and deckhands.”

After being acquitted from 22 fisheries charges in 2019, Sammy faced five new charges in 2021 for crab fishing in səl̓ilw̓ət (Burrard Inlet), a closed area, without a licence. Sammy says the 250 crabs on his boat were leftovers from a catch from the Nanaimo area, where he did have a licence. His intention was to transport the crab to his family in North Vancouver.

Sammy admits he made a mistake in bringing Scott Steer with him, who was banned from boarding any commercial boat, including Sammy’s.

When a Vancouver SeaBus captain reported suspicious traffic to the Coast Guard, Fisheries and Oceans headed for Sammy’s boat, recognizing Steer at the helm, according to court records. “I guess he got scared,” said Sammy. Steer took them on a high-speed boat chase while Sammy lay on the deck. He was having a diabetic attack.

When Fisheries and Oceans finally caught up with them, Sammy said he explained he was diabetic and wasn’t feeling good. Sammy alleged he was kept on the water for six hours, while handcuffed from behind, despite telling the fisheries officers it hurt. “I’m a big guy,” said Sammy. He recalled he asked why Steer was allowed to have his handcuffs in front of him in a comfortable position, while Sammy’s shoulders felt pulled from the cuffs.

Eventually, the two men were transferred to the North Vancouver RCMP office where they called an ambulance to check on his blood sugar. “The paramedics were upset I’d been kept for so long,” said Sammy. His blood sugar level was intensely high. “They said I should have been taken to the hospital right away.”

In the ruling, Sammy’s diabetic attack was taken into account to the extent that, “He was experiencing some physical distress due to his suffering from diabetes.” It continued, “He was co-operative with the police and was, ultimately, taken to the hospital and then released.” No additional context was provided.

“There is no evidence that Mr. Williams was the operating mind of the operation and certainly no evidence that he was responsible for the high-speed chase through a darkened Burrard Inlet,” the ruling stated.

Despite this, Sammy, who had no prior criminal record, was sentenced to a three-year probation and a $6,000 fine. His boat, worth $20,000, was forfeited in Steer’s trial, despite it being Sammy’s property.

“Now I’ve got no boat, no vehicle. I lost everything,” he said. “Everything I worked hard for.”

Sammy also said he regularly experiences discrimination on the water fishing T’aaq-wiihak — with permission from the Hereditary Chiefs. To fish T’aaq-wiihak, fishers are required to fly a red flag onboard their vessel.

“It’s a red flag — a target,” said Sammy. “When me and my brother were fishing, there was probably one hundred sports boats out. DFO motored past every sports boat and came straight for us.”

For Sammy, fishing on his ancestral waters has been a fleeting refuge for him throughout his life. He struggled both in childhood and as a teenager. “We lost my mom, my sister, my grandma and my brother all within a year,” he said. “I’ve been depressed for a long time.”

One year on from the Five Nations ruling, Ray remained concerned about recreational fisheries, which he still believes take priority over their rights-based fisheries. He said he’s seen between two and three hundred recreational fishers in the area at any one time.

“There’s just too many [recreational] fishermen milking our stock out of the ocean,” said Ray.

Kadin Snook, fisheries co-ordinator at Ha’oom Fisheries Society, says part of the problem is that the recreation fishery is seen as non-harmful.

“The thinking is, if I’m only catching two chinook a day, I can’t possibly be doing any harm,” he said. “But vessel participation is huge.”

British Columbia has a reputation for being one of the greatest saltwater fishing destinations in the world — with more than 300,000 fishers participating in the tidal fishery every year, mostly for salmon.

Snook, who is Mowachaht/Muchalaht, worries about other impacts of recreational fishing.

Rarely considered, he said, is the harm caused by the catch and release of unwanted fish by recreational fishers. He said, in a single day, there could be up to 4,000 fishers in the Mowachaht/Muchalaht area. That’s a lot of injured fish.

Commercial and rights-based fishers aren’t afforded the same flexibility from Fisheries and Oceans as recreational fishers, who can fish both inshore and offshore, and are not required to report their catch, said Snook.

Snook argues that the guiding industry, which requires only a recreational licence, is unfair.

“There’s commercial interest and a lot of expertise, yet they are operating on a [recreational] licence,” he said. “They’re everywhere, and they’re not being monitored.”

Ray said he would like to see recreational licence fees flow to the Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation when recreation fishers harvest from the territory’s waters.

“DFO has no business in charging the sports fishermen to fish in our territory, in our ocean, our food,” he said. “It has to be our Ha’wiih [Hereditary Chiefs] that approves fishers to fish in our area.”

Ray also said fees should be increased to slow down recreational fisheries. In 2023/2024, an annual recreational licence in tidal waters costs a Canadian resident only $22.59, or $108.64 for a non-resident. To catch salmon, fishers must also purchase a “salmon conservation stamp” for $6.46.

“I can see it failing in front of my eyes and we’re not doing anything about it,” said Ray. “It’s important for the future of our children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren to see the changes that we might be making today, starting today.”

Some T’aaq-wiihak fishers have been attempting to fish as a group, but Fisheries and Oceans has, in some cases, shifted their attention towards targeting fish buyers, explained Sammy. “They raided our buyer in Quadra [Island],” said Sammy. “Thirty fisheries officers because our fish was sold there.”

Sammy hopes that T’aaq-wiihak fishers and buyers can unite in defiance of colonial laws. “As long as the fish buyer knows you’ll stand behind him in court,” said Sammy, “Then our fishing rights will go a long way.”

In the future, Sammy would like to see an Indigenous-owned fish purchasing plant. “When you own that fish plant and you’re the one selling it for your people, then everyone gets paid a lot more,” said Sammy. “It’s pretty much cutting out the middleman.”

Ultimately, Sammy said, he just wants his people to live healthy lives.

“One day we’ll have a wealthy lifestyle. Our kids won’t have to worry about anything. I’ll go out, I’ll work hard to make sure we have a roof over our head, clothes on the kids’ back and food in the freezer — and that’ll be all,” said Sammy. “It’s a struggle right now, but I’m hoping one day it won’t be.”

This story was produced as part of the Fish Outlaws project, a multidisciplinary collaboration supported by the National Geographic Society. The Fish Outlaws project launched a living website on Earth Day featuring stories, research and participatory opportunities exploring how destructive colonial fisheries management and environmental practices have compromised Indigenous fishing rights and community wellbeing.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

B.C. previously allowed mineral claims without First Nations consultation. It was court-ordered to fulfill its...

British Columbia has vowed to fast-track several mining projects in an effort to blunt the...

Alberta introduced North America’s first industrial carbon tax in 2007. Now an industry email obtained...